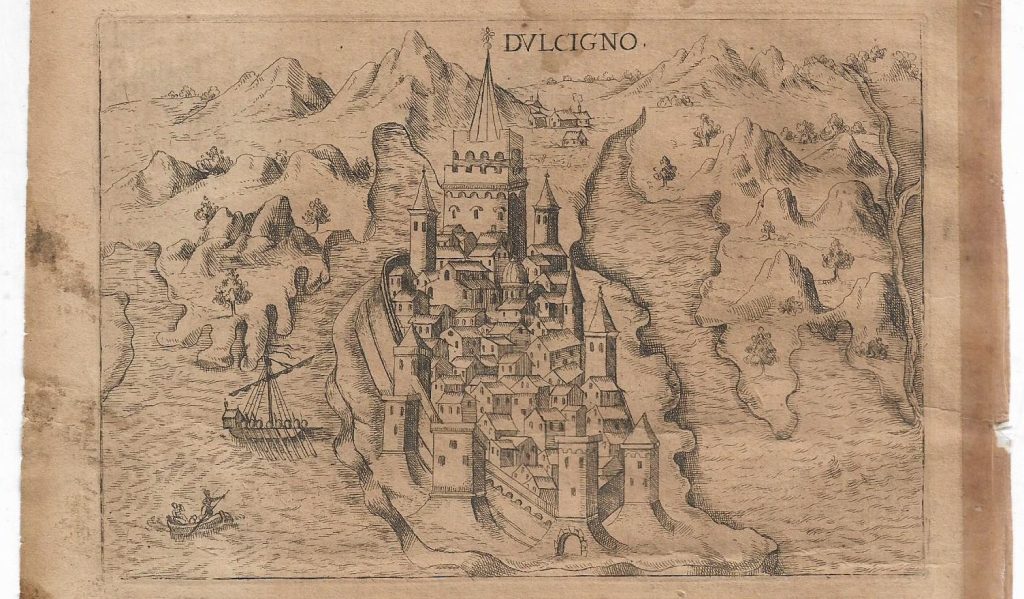

The Merchant Fleet of Ulqin (Albanian: Flota Tregtare e Ulqinit or Detaria e Ulqinit) was a fleet of Albanian trading ships and vessels based in Ulcinj, operating in and around the Adriatic and Mediterranean coast between c. 1420 and 1870s, changing and expanding depending on Venetian-Ottoman conflicts and commercial demands. The region was heavily pested during the Cretan War (1645-1669) with pirates who both raided ships in Herceg Novi and in Shkoder. During the Ottoman rule (1571-1880) the fleet of Ulcinj became the main pillar of the Ottoman Empire with Albanian sailors barely recognizing the Ottoman authorities.

In 1710 the fleet grew in 250-300 ships with a crew of 4000-5000. In 1710, the Venetian consul in Durrës and Boka hoped that in the chaos that ensued the flet of Ulcinj would be destroyed. From Shkodër, there were around 804 traders with 200 being from Ulcinj. For a long time, the traders traded with the Republic of Ragusa. In the 17th century, the east Mediterranean was dominated by French and Venetian ships, however, Dulcinian ships participated in the transit trade, with improved odds after the Russo-Turkish War (1768-1774).

On November 2, 1772, the fleet was hired by the Ottomans to fight the Russian armada led by Konyef in the west of Peloponnes close to Patros Island in the Aegean Sea. The constant wars between the Ottomans and the Venetians severely effected the trade. Despite the military elements of the fleet, it was mostly commercial. The strong fleet made Ulcinj into a trading center. During the second half of the 18th century, the fleet expanded its trade as the demands for cotton increased in European countries.

The first sign of a merchant fleet in Ulcinj is from 1420 when the city gave itself up to Venice out of fear from the Ottomans, according to a column in the English newspaper Chelsea Herald (1873-1909) published in 1880. Generally, Albanian merchants from Ulcinj had been formed, alongside Greeks, before 1750.

In the 17th century, continuing to the 18th century, the fleet expanded. During the first 6 months of the year 1711 there were 12 different sailboats of various tonnages. Durrës Venetian consul, Peter Rosa, sent a letter in June 1707, to the Venetian Senate, explaining that the fleet of Ulcinj consisted of 250 sailboats of different sizes. The Venetian merchant fleet felt threatened and tried to curb the fleet of Ulcinj.

In 1709, when the Venetian-Turkish war broke out, the Venetians closed their consulate in Durrës thus endangering the trade for the fleets. Venetian trade authorities improved the general trade agreements by allowing Shkodër merchants to accompany the wares to Venice who would then load other goods on their way back, with mostly Ulcinj vessels sailing. However as rivalry increased, Venice ordered a prohibition from the Porte forbidding the ships from Ulcinj to transport cereals.

In 1720, the Ulcinj trading fleet became the protagonist in the trade and mediation between Habsburg and Venice, dealing mostly in salted fish, liquor, cheese, turtles, silk, linseed, dried fruits, wax, soap, tallow, silk, cotton, timber, pitch, tar and, above all, cereals, tobacco and olive oil and raisins. The fleet also improved the trading relations and communication between the Adriatic and Mediterranean.

In 1745, the Dulcignote vessels expanded the trade in Trieste, Ancona and Apulia reaching high trade in 1744-46 and 1746-51. The expanding fleets of Shkoder along with Dulcigno made Venice nervous. In 1750, the merchant fleet of Ulcinj traded in timber and cereal numbering around 200 ships.

As the competition increased, two rival merchant fleets were soon created: A Greek with crew members from Psara, Hydra and Spetsai, and the other an Albanian with members from Ulcinj, Vlorë and Durrës, and a third fleet from Ragusa joined in. These fleets fought over the markets of ideology and the purchasing and transport of goods. In 1786, the Greek-Albanian merchant fleets consisted of 400 ships, and in 1812, of more than 600.

Throughout the 1750s, the Ulcinj pirates made trading worse for the fleet but after the Bushati reforms, the pirates quickly were transformed to a large commercial maritime power thus rivaling both Venetian and Ragusan fleets. In 1779, the northern regions of Shkodra districts had to import grain from central Albania, but because of the wars between Albanian nobles, the price of grain was inflated by merchants, and the Pasha of Shkodër interfered by raising the prices of grain and collaborating with the merchant ships of Ulcinj, numbering 200 at the bay, with some belonging to the Bushati family.

Before 1779, the trade was dominated by Venetian subjects, and Kurd Pasha tried to stop the merchant fleet of Ulcinj. However, in 1780, Mahmud Pasha lifted the ban and focused his effort on the fleet again. In 1781, the Agas of Ulcinj demanded that the ronda tax system be abolished which was granted. Kara Mahmud Pasha’s tax liberation policy “mukataa” for the fleet of Ulcinj made things worse for Venice as the Albanian merchants now profited more. In 1783, Kara Mahmud Pasha traveled to Dubrovnik to see if the Franciscan friars would help him. He was, however, not greeted well, mostly due to the financial difficulty as a result of the Ulcinj trading fleet’s tax liberation. The visit was recorded by Pater Balneo who prepared for the visitation. Mahmud Pasha returned home and canceled the commercial treaties with Dubrovnik.

The Ulcinj traders transported wheat to Venice, Istria, Trieste and also Genoa. During the Ottoman period, the traders occasionally served as sailors for the Porte. In 1717, Venice proposed a resolution of arming ships against and the privateers of Ulcinj in order to allow free trade in the Adriatic sea. According to A. Baldacci, the fleet had 500 ships transporting mainly grain, salt, tobacco and wool.

In 1818, the fleet consisted of 400 ships. In 1821, when the Austro-Hungarian war fleet began circulating in the Adriatic, the fleet of Ulcinj decreased. The French consul in Shkodër, Hecguard, stated that the sailors made ships weighing anything between 100 and 200 tons. In 1737, even larger ships were built but the Porte forbade the construction and halted it. In 1845, the fleet competed with Austrian trade. The demand of sardines necessary for the Catholic population of Ulcinj used in festivities was possible thanks to the fleet. Known traders amongst many others were the tartanes of Ulcinj.

During the 19th century, the fleet was first mentioned in a written letter in 1854 by Hahn, the Austrian consul in Shkodër. During the Russo-Turkish war (1876-1878), the fleet had 400 ships. During the Montenegrin period (1880-1918), the fleet had 107 ships

References

- Hetzer, Armin (1984). Geschichte des Buchhandels in Albanien: Prolegomena zu einer Literatursoziologie (in German). In Kommission bei O. Harrassowitz. p. 30. ISBN9783447025249.

(Translation) The statement seems to me to have been made only to make the Albanian merchant fleet of Ulcinj appear in a favorable light. As such, the Ulqinaks were considered pirates, not so much as Fraschtschiffer.

- Hadzÿibrahimovic«, Maksut Dzÿ (2017). “Istorija ulcinjskog gusarstva u periodu otomanske vladavine”. ALMANAH – Cÿasopis za proucÿavanje, prezentaciju I zasÿtitu kulturno-istorijske basÿtine Bosÿnjaka/Muslimana (in Bosnian). pp. 145Ð168.

- Bongers, A. (1969). SŸdosteuropa-Jahrbuch (in German). A. Bongers. p. 194.

(Translation) From an Albanian merchant fleet can be up to the city of Ulcinj no question. There was a stock of about 230-300 ships with about 4 000-5000 sailors. In 1818 one speaks of 400 units. The city of Ragusa should …

- Curtis, Matthew Cowan. Slavic-Albanian Language Contact, Convergence, and Coexistence. ProQuest LLC. p. 344. ISBN9781267580337. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

(Translation) When the OttomanÐRussian war began (lit. had begun) in 1710, the Venetian consul in Durr’s and Boka hoped (lit. have hoped) that in the general chaos that was predicted in the Balkans that the fleet of Ulcinj would also be destroyed

. - Savasi, Denis. 1770 Cesme Deniz Savasi. 1768-1774, Osmanli Rusi Savaslari. Battle of Cesme 1770 (PDF). Ali Riza Isipek, Oguz Aydemir. p. 261.

(Translation) In the west of Peloponnes Peninsula the Konyef Fleet of the Russians was in combat against the Ulgun (Ulcinj) Fleet in the environment of Patros island on November 8, and it returned to Aegean Sea on November 15, 1772.

- Leger, Louis (1915). La Serbie au Moyen åge. (premier article) [compte-rendu] Constantin Jirecÿek. L’ƒtat et la sociŽtŽ dans la Serbie du Moyen åge (extrait des MŽmoires de l’AcadŽmie des Sciences de Vienne, 1912) (PDF). Vienna. p. 222. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

(Translation) The maritime cities of Cattaro, Dulcigno and Budua provided the elements of a commercial rather than military fleet. In some cases special treaties ensured the help of the Ragusa flotilla.

- Cÿolakovic«, Zlatan; Cÿirgic«, Adnan (2008). The Epics of Avdo Me?edovic« (in Serbian). Almanah. p. 307. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

(Translation) As a naval and commercial center, Ulcinj developed under the protection of the city fortification, as well as its own merchant and naval fleet, coastal, long and large navigation, in which the main naval base was located, developed as a trading center …

- Lefteris Stavrianos, The Balkans Since 1453, Rinehart & Co., New York 1958. | Ottoman Empire | Balkans. p. 161. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- The city of Ulcinj" (PDF). The Chelsea Herald. 1880. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

(Translation) When, in 1420, it gave itself up to the Venetians, from fear of the Turks, it had considerable mercantile fleet and carrying trade. It eventually fell into the hands of the Turks in 1671, after undergoing a protracted siege, and from that moment its commerce dwindled and disappeared and its roadstead became the haunt of pirates, who ravaged the coasts

. - The Journal of economic history. Economic History Association at the University of Pennsylvania. 1960. p. 275. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- Frasheri, Kristo (1964). THE HISTORY OF ALBANIA (a brief survey). Tirana. pp. 97Ð98.

in various cities of the country, even outside Albania, especially at Venice and at Trieste. The merchants sold in foreign lands agricultural, handicraft and dairy products, and brought thence the products of European industry. The development of commerce brought in its train the growth of the Albanian mercantile fleet. The city with the greatest fleet was Ulcinj (Dulcigno) whose inhabitants distinguished themselves as bold sailors.

- Sarai, Alvin; Xhufi, P‘llumb (2016). The Trade Relations between the Sanjak of Scutari (Shkodra) and the Republic of Venice in the First Half of the XVIIIth Century. pp. 61Ð67. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- Andreozzi, Daniele. Daniele Andreozzi e Loredana Panariti, Trieste and the Ottoman Empire in Eighteenth Century, in Barbara Schimidt-Haberkamp (ed.), Europe und Turkey in the 18th Century, Bonn University Press – V&R unipress, Gottingen 2011, pp. 219 – 230. pp. 14–16, 224, . Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Stoianovich, Traian (2015). Balkan Worlds: The First and Last Europe: The First and Last Europe. Routledge. ISBN9781317476146. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ƒCONOMES MƒDITERRANƒENNES ƒQUILIBRES ET INTERCOMMUNICATIONS XlIIe-XIXe sicles (PDF). Athen: ACTES DU Ile COLLOQUE INTERNATIONAL D’HISTOIRE. 1983. pp. 209, 213, 257, 541, 547. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- GJELI, ARDIT (2018). BETWEEN REBELLION AND OBEDIENCE: THE RISE AND FALL OF BUSHATLI MAHMUD PASHA OF SHKODRA (1752-1796) (PDF). A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES OF IúSTANBUL SüEHIúR UNIVERSITY. pp. 30, 60, 69, 71, . Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Cova, Ugo (1989). MINISTERO PER I BENI CULTURALI E AMBIENTALI QUADERNI DELLA RASSEGNA DEGLI ARCHIVI DI STATO FONTI GIUDIZIARIE E MILITARI AUSTRIACHE PER LA STORIA DELLA VENEZIA GIULIA OBERSTE JUSTIZSTELLE E INNEROSTERREICHISCHER HOFKRIEGSRA T (PDF). UFFICIO CENTRALE PER I BENI ARCHIVISTICI DIVISIONE STUDI E PUBBUCAZIONI. p. 154.

Sovrana risoluzione e altri provvedimenti relativi all’armamento di navi diá Segna contro i corsari di Dulcigno, per permettere il libero commercio nel mare Adriatico, cc. 1-1 O, ted. (Translation: In 1717, Sovereign Resolution and other provisions relating to the arming of Shiman ships against the privateers of Ulcinj, to allow free trade in the Adriatic Sea, cc. 1-1 O, ted.)

- Vejsa, Lirjet? Avdiu (2018). OLD CITY ULQIN THE ANALYSIS OF DEVELOPMENTS SINCE THE MID-20TH CENTURY AN ANCILLARY APROACH TO CONSERVE THE AUTHENTICITY (PDF). ALBANIAN AMERICAN CULTURAL FOUNDATION – AACF. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

17th century – according to A. Baldacci, UlcinjÕs fleet had 500 sailing ships navigating throughout the Mediterranean Sea, transporting mainly grain, salt, tobacco and wool. During this period, Ulcinj had the shipyard where larger (various tonnages) and faster sailing vessels were built such as galleons (alb. galeota), run by qualified and certified captains.

- Papajani, Prof. Dr. Adrian (2015). Aspects of Navigation Development in the Region of Shkodra during XVIII Century and the Beginning of XIX Century. Elbasan: Faculty of Social Education, Department of Social Sciences, University ÒAleksand‘r XhuvaniÓ, Elbasan, Albania. pp. 156, 157. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

During the eighteenth century there was a comprehensive strengthening of Ulcinj merchant fleet. It increased mainly through the construction of new vessels of various tonnages. Consequently, in 1818, this fleet consisted of 400 vessels units.

- “Historia e Ulqinit n’ syt’ e udh’rr’fyesit m’ t’ njohur gjerman”. KOHA.net (in Albanian). No. Translation: This led the Ulcinj fleet to create a great competition for the Austrian merchant fleet. 19 February 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- Luetic«, Josip (1959). O pomorstvu Dubrovacÿke Republike u XVIII. stoljec«u (in Croatian). Jugoslavenska akademija u zagrebu, Pomorski muzej. p. 193. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

(Translation) foreign merchantmen who took part in the transport of our goods of transit and imported in Dubrovnik goods of origin of the Levant or Occident, the most often mentioned are tartanes of Ulcinj, French polacres, sailboats Venetian, Austrian, English and Swedish.

- Franetovic«-Bžre, Dinko (1960). Historija pomorstva i ribarstva Crne Gore do 1918 godine (in Croatian). p. 265. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

(Translation) The first written evidence of the numerous condition of the Ulcinj merchant navy was presented in 1854 by Hahn, the Austrian consul in Shkoder.