This text was taken from Fitim Rifatis publication “Kryengritjet shqiptare në Kosovë si alternativë çlirimi nga sundimi serbo-malazez (1913-1914)”. Journal of Balkan studies, 2021.

Abstract: The Albanian armed uprisings against the Serbian and Montenegrin occupation and annexation of Kosovo, present a realistic tableau of a historical period (September 1913 – April 1914) until the Albanians were confronting with three alternatives for their future: organizing the armed uprising for liberation, emigration and assimilation. This study article explicates the attitude of the Kingdom of Serbia and the Kingdom of Montenegrotowards Albanians, primarily to those Muslims, the causes of the organization of armed uprisings for liberation and their results. Through archival sources, the press of that time, published documents and historiographical literature, presented new information and interpretations whom enlighten and construct events, occurrences and personalities, which have characterized Kosovo during that time. Increasingly, relying on the source data, reached in ascertainment that the Serbo-Montenegrin kingdoms in Kosovo intended to implementation the state policies whom lead towards national, demographic, cultural and radical changes to the detriment of the Albanian population.

The Serbian-Montenegro attitude towards the Albanians in Kosovo and the position of women

The Montenegrin-Serb invasion of Kosovo in October-November 1912 brought a new situation for the Albanian population. The Kingdom of Serbia and the Kingdom of Montenegro, although having proclaimed that Albanians in Kosovo would be guaranteed their rights and property, did not implement the decisions of the Conference of Ambassadors. On the contrary, in the political mess created during and after the Balkan Wars, they took an opposite attitude towards Albanians.

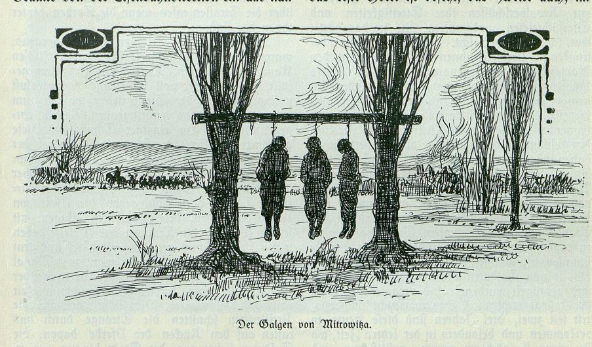

Save disarmament, the Serbian state made efforts to attract special collaborators from ranks of Albanians, to put them at the service of his interests. (Војновић, 631:1984) In fact, the Albanian leaders of Kosovo with a national orientation, but also the civil population, refused to cooperate with the Serbian authorities. For this reason, without applying judicial procedures, they were imprisoned, isolated, exiled and killed. Among them there were also the leaders of Drenica such as: Halil Haxhia, Hetem Kozhica, Fejzullah Lubaveci, Temë Dobrosheci, Rexhep Llausha and eighteen other leaders, who were executed in Kacanik. (AIHT, September 11, 1:1913; Liri e Albania, 2:1913)

According to the propaganda and chauvinistic policy of the Serbo-Montenegro governments, the Albanians of Kosovo did not constitute any element of cultural, historical and national importance. (Lukač, 264:1981) They were considered “wild” (Војновић, 371:1984), “bloodthirsty” (Cana, 201:1997), “deceitful”, “cunning”, “disloyal”, “conservative”, “regressive” (Политика, 1:1914), “pissed” etc. (Shala, 150 :1990) Military, police and state administration, and even the Serbian element in Kosovo had free hands to act against the Albanians, who were tortured and beaten to death. (AIHT, January 10, 2 :1914) Accordingly, this attitude brought the tension of inter-ethnic relations and the promotion of conflicts between Albanians and Serbs in Kosovo. These regimes implemented a policy of hegemony and destruction towards Albanians through the burning of villages, massacring the inhabitants, plundering the wealth and robbing properties. (АВИ, 2 February 1:1913; Çeku & Destani, 52-49 :2015; Freundlich, 39-7 :2010).

The Serb agenda for Kosovo and the Albanians, which had its main basis in the “Project Načertania of Ilia Garashanini , the principle was: “Serbianism at any cost”. (AIHT, 29 September 1913: 2; Germek, Gjidara & Šimac, 2010: 29-104; Verli, 1998: 21-29; Bajrami, 2004: 9-64). The Inspector of the Serbian Police in Skopje, Mihailo Cerovic, threatened and blackmailed Albanians, rushing towards them and saying:”I will cut off their heads and legs if they don’t become Serbs“. (Birth of Albania, 1913:2)

In this context, the aim of the Serbo-Montenegrin policy in Kosovo was political and economical oppression of the Albanians, to expel them from their homeland and establish a Serbian colony.

Serbo-Montenegrin policies, apart from the pressure on thesefamilies, aimed at attracting these leaders to Kosovo, to neutralize the efforts that they did for the liberation of Kosovo. The Serbo-Montenegrin military regime tried to antagonize the Albanians, inciting divisions on religious grounds between them.

Catholic Albanians in Kosovo faced claims to align them within the framework and interests of Serbian and Montenegrin politics and to bring them into conflict with Muslim Albanians. (AIHT, 18 March 1914: 1) Another measure taken by the Serbo-Montenegrin authorities towards the Albanians was the service of mandatory military service. Albanians were obliged to respond to invitations, which were accompanied by threats to perform military service. (New Albania, 1913: 3) In case that they refuse or do not respond in time to the call to terminate this service, severe sanctions followed, including ill-treatment and imprisonment. (AIHT, 23 January 1914:3)

These harsh measures resulted in a significant migration out of Kosovo of able-bodied persons and at the same time of their families, who wanted to avoid the military service and penalties for non-compliance (AIHT, January 6, 1914: 1) These measures were contrary to the decisions of the Conference of Ambassadors in London and those of the signed Ottoman-Serbian Agreement in Istanbul, on March 14, 1914. This agreement guaranteed civil rights the Muslim population under the Kingdom of Serbia.

The agreement meant that Albanians were not obliged to pay any kind of tax, it did not force them to submit to military power and it guaranteed the right to inviolability of property, promised local self-government, respect for faith, customs and education. This agreement was a kind of pressure on the Kingdom of Serbia to preserve the Muslim population in Kosovo, but it was not implemented in practice. It did not protect Albanians from denationalization and emigration. (ASHAK, 1912-1913: 2; Politics, 1914: 2)

Ratification of this agreement did not happen because the Kingdom of Serbia, both before and after its signing, implemented a policy of serbization in Kosovo. (Malcolm, 2011: 336) Regarding the non-respect of this agreement, the British ambassador in Belgrade, Dayrell Crackanthorpe, on May 26, 1914, sent a confidential report to the Foreign Secretary, Edward Grey, in which, among other things, underlined the following:

“Administrative offices in the new territories (Kosovo and other places, F. R.) was filled mainly with a group of inexperienced and unscrupulous officials, who abused their authority in every direction. They left no stone unturned for it filled their pockets and they pursued a policy of open oppression of foreign minorities. Minorities in the annexed territories will continue to suffer in terms of their civil and religious liberties“. (Čeku & Destani, 2015: 149-150)

Women in Kosovo, who before the Serbo-Montenegrin invasion, although they lived in a conservative society and in gender inequality, had certain rights that were guaranteed by the Ottoman legal system and customary law. (Musaj, 1998: 59) However, the condition of women under the new occupation deteriorated tremendously. Despite living in a patriarchal society with old traditions (Begolli, 1984: 17-30), the customs was threatened, because it faced problems caused by the new political circumstances.

The Serbian authorities targeted Albanian women with physical and psychological abuse. They were faced with a situation exposed to constant risks (torture, murder, dishonor, forced marriage and conversions) and were often unprotected from the crimes of military, police and state operations. Under the Serbo-Montenegrin occupation, women was denied any social and cultural rights. Limited to the family economy, in addition to the activity in housework, such as: preparing food and taking care of children, livestock and poultry, the woman also worked the agricultural land, such as: planting, harvesting, cleaning, mowing hay and collecting it in the field. (Berisha, 2004: 66-71; Populli, 1915: 4)

However, the role and contribution in the family was trampled on, wasted, punished and overthrown as a result of the brutality of the Serbo-Montenegrin invaders. During this period in Kosovo, according to legal, religious and customary norms, the woman was obliged to perform the activity at home and whenever she went outwalls of the house, despite the fact that it was not practiced in general, especially in the rural areas, she was forced to cover her face with a scarf and her body with a veil. (Moses,1998: 59).

The Serbian-Montenegrin authorities in Kosovo refused to respect the cultural and dress tradition of the Albanian woman. In this context, there were cases of abuse during ceremonial acts of marriages, coronations and family holidays, in which the Albanian woman marked special moments of her life. Administrative bodies intervened, who not only stopped and disrupted the festive ceremonies, but also ordered that the Albanian girls and womento remove the veil from their heads, prejudicing and violating honor and trust.(AIHT, March 19, 1914: 3)

The Albanian woman was seriously endangered during the military and police control actions against houses and families, which were suspected of subversive activities against the Serbo-Montenegrin regime. In the absence of men, women were threatened, insulted and robbed by force. Cases were often noted in Kosovo. In January 1914, on the pretext of capturing the Albanian insurgents, the Serbian authorities carried out a control operation in the house of Fazli Kabashi in Apterushe of Rahovec. During this operation, the secretary of the municipality of Zacishte and the Serbian gendarmes insulted the women with harsh words. However, the owner of the house and the other men reacted, fought with the secretary and the gendarmes, and as a result the son of Kabashi was killed and several guests were injured. (AIHT, January 16, 1914: 2)

With these actions, the normal life of the Albanian women became uncertain and impossible in front of an anti-Albanian military and state machinery. Targeted by the administrations attacks Serbo-Montenegrins persecuted Catholic spiritual representatives, such as nuns. Nuns of the Catholic Monastery in Prizren were provoked and were attacked by Serbian soldiers. In order to compromise the the nuns mission, the Serbian government also questioned their religious service. (Војновић, 1984: 366).

Albanian women, like men, also faced the process of religious conversion, which was run by state bodies and the Serbo-Montenegrin Orthodox Church. Serbian and Montenegrin looting, raiding, torture, conversion and the killing of Albanians had almost become a daily occurrence. In the spring of 1914, in one of these operations, seven Serbian soldiers entered the house of an Albanian in the evening, where they forcibly asked the owner to give them the money. Dissatisfied with that, leaving, they robbed his two daughters, who forced them to deny their religion Islam and to declare that from now on they embraced the Christian religion, namely the Orthodox. (Taraboshi, 1914: 2)

The abuses and violence that the Serbo-Montenegro state, military and police administration exercised against the Albanian women in Kosovo deepened especially in cases of crises and armed revolts of the Albanians. After the armed uprising of the Albanians in the spring of 1914, as a sign of revenge, the Serbian army and armed civilian groups behaved inhumanely towards the Albanian woman. The Albanian press also reported on the Serbian atrocities. The Taraboshi newspaper, dated April 17-18, 1914, published an article in Shkodër, writing that: “The women were to be raped and then killed“. (Taraboshi, 1914: 3).

The Serbian minority that lived in Kosovo either supported the Serbian army in such enterprises or participated in the atrocities. Thus, there were many cases when local Serbs took advantage of the political circumstances to commit inhumane acts against Albanian girls and women. At this time there were more cases when Albanian girls in the villages of Kamenica were violently robbed by the infamous Koica Popovic from Maroca, who was known for his inhumane actions against the Albanians of this region. He reportedly robbed two Albanian girls in the villages of Kranidell and Kremenaté.(Latifi & Sermoxhaj, 2002: 28; Redenica, 2014: 48-53)

During this time, the bodies of the Serbian military and state administration, during many operations they undertook against Albanian families, often ended them by raping Albanian women and girls. (Albanian Besa, 1915: 2-3) In the circumstances of such as a military occupation and regime, social, economic and cultural positions of Albanians was absolutely oppressive and discriminatory in every aspect of life.

The Armed Uprising of 1914 against the Serbo-Montenegrin oppression

As a result of years of severe oppression of Albanians in Kosovo, several armed uprisings occured.

Albanians, due to political, economic, socia, cultural and educational divergences, not seeing their perspective within the arbitrary and violent Serbian-Montenegro government, were faced with three options for their future:

- Organizing an uprising, as a last chance to break free from systematic violence or eventually to be sacrificed in their lands;

- Emigration as an opportunity to escape from the dire situation with the hope of a safer life;

- Assimilation or Slavization, which meant accepting the Serbo-Montenegrin occupation and administration with all its political, economic, social and cultural-educational dimensions.From the beginning, the Albanians in Kosovo did not accept the Serbian and Montenegrin occupation(Dreshaj, 1991: 256) and did not agree with the decisions of the Conference of Ambassadorsin London, for the annexation of their vices to the Kingdom of Serbia and Montenegro. (AIHT, 26September 1913: 1)

At the beginning of September 1913, the Serbian state bodies officially announced the annexation of Kosovo and other Albanian provinces. (Verli, 2004: 163) The Albanian leaders, as soon as they were informed of this decision, through a memorandum sent from Kosovo, immediately requested from the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the six Powers not only to revise the decisions of London, but to ameliorate the injustices towards the Albanians. They complained about the violence and atrocities they were experiencing as a result of this regime. (Liberty of Albania, 1913: 2)

According to the Serbian social democratic politician, Kosta Novakovic, by the end of 1913, this regime exterminated more than 120,000 Albanians of all ages, as well as forcibly displaced more than 50,000itself in the direction of the Ottoman Empire and Albania. (Novakovic, 1990: 305) Although the figures on the number of Albanians killed and deported continue to be undetermined, according to the Report of the International Commission of Inquiry, prepared by Carnegie Foundation for International Peace (1914), states:

“Entire houses and villages were reduced to ashes and dust, many innocent people and so onunarmed were massacred, incredible acts of violence, plunder and brutality of every kind—such were the means which were and are still being used bythe Serbian-Montenegrin army, with the aim of radically changing the ethnic structureof regions inhabited exclusively by Albanians“. (Carnegie, 1914: 151).

The leaders of the national movement from Kosovo, who operated in the Albanian state, started to take organizational measures to express their dissatisfaction through armed actions, while within the annexed territories, the Albanians carried out attacks and clandestine actions, the targets of which were the Serbo-Montenegrin military, police and state representatives. (Cana, 1997: 300-307) Only killing one gendarmerie in the village of Gjakova, on September 7, 1913, incited the Serbian government to order the burning of the village and 32 inhabitants in Ujz, and the massacre of the population of Fshaj as a sign of revenges, as well as the burning of the village of Smaç. (AIHT, September 1913: 2)

On the other hand, the arbitrary collection of historical and forgotten taxes from the Ottoman period, even those officially discarded, as well as newly imposed taxes, led to a statement being made by British vice-consul in Skopje, Walter Divie Peckham: “They had come to the tip of Albanians noses”. (Duke, 2012: 123)

In this tense and unbearable situation, the highest military bodies of the Kingdom of Serbia, being aware of the Albanian movements around Gjakova and Prizren, ordered the military commands of the districts and districts of Novi Pazar, Mitrovica, Prizren, Pristina and Gjakova, to put their divisions into operation with purpose of guarding the border, security and preventing a possible uprising among Kosovo Albanians. (ASHAK, September 5, 1913: 2).

Albanians from Kosovo concentrated in Albania under the direction of Isa Boletini, Bajram Curri, Riza Gjakova, Mehmet Derralla and Bajram Daklan, were preparing for an armed attack against the Serbo-Montenegrin government. Their goal was the liberation of Kosovo and other occupied and annexed regions and their unification with Albania. To achieve this goal, they joined the “Shkipnia” society. (Dzambazovski,1983: 252; Duka, 2012: 242) In the second half of September 1913, the attacks began against Serbian military forces in the border area with Luma province.(ďambazovski, 1983: 262)

According to the information provided by the Ministry of Works and Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of Serbia, these attacks were re-framed as an alleged “Albanian invasion of Serbian territory” (Marcovitch, 1921: 15) being prepared and orchestrated by the Provisional Government of Vlora for a period of three months, under the leadership of Minister Hasan Prishtin and Isa Boletini and under the continuous agitation of Bajram Curri and Riza Gjakova and even the Austro-Hungarians.

The Albanian forced managed to break through the border control of the army, orienting their attack in three directions: towards Dibra, Ohrid and Prizren. The Serbian government was concerned about the actions of the Albanians and notified the Great Powers. To counter organized insurgency the Serbian authorities ordered the addition of military forces to the combat zones. (Lukač, 1981: 377-378) The Government of Vlora, headed by Ismail Qemali, was obliged to maintain a restrained attitude and not to be involved through official mechanisms in the ranks of this uprising (History of the Albanian People, 2007: 431)

To suppress this uprising, the Kingdom of Serbia gathered 20,000 – 50,000 soldiers. (AIHT, 25 September 1913: 1;Perlindja e Shqipënia, 1913: 6) The uprising did not have the same intensity and did not start simultaneously in all regions (Murzaku, 1996: 125). Never the less, it spread deeply in Kosovo to the vicinity of Pristina, to the area of Drenica, and to the surroundings of Mitrovica (AIHT, October 9, 1913: 3) and Dukagjin Plain (Duka, 2012:117, 216-217). Eventually it included all the Albanian territories. (Liberty of Albania, 1913:1) This uprising included Skopje, Tetovo, Gostivar, Kicova, Manastir and their surroundings. (Xhemaili, 2008: 112; Destani & Elsie, 2018: 252-270)

Alarm and panic gripped the Serbian army. Consequently, there was a lack of food and civilians died. (Duka, 2012: 333) After a few days of fighting in Junik, Reke te Keqe, the Gjakova highlands, Bec and Duškaja, the Montenegrin army killed 87 men in Ponošec of Gjakova as a sign of revenge for two soldiers killed and one wounded. (New Albania, 1913: 2) The troops massacred the population, burned and destroyed Albanian villages such as Maznik, Jabllanicë, Zhabel, Novoselle, Dushkajë, Strellc, Popoc etc. (AIHT, September 27, 1913: 1) At that time, the Serbian social democratic press reported from the scene of the Serbian armys reprisals against the Albanians. A Serbian soldier wrote to the newspaper “Radnicke novine”, stating that there were:”Villages with a hundred, a hundred and fifty, two hundred houses where there was no man anymore. We killed and massacred them with our bayonets”. (Swire, 2005: 152; Duka, 2012: 123).

The deterrence of the Albanians by the Serbian army after a week of fighting created suitable conditions for the High Command to use repressive measures against the Albanians. The Serbian army and the civilian groups killed the Albanian population in Kosovo, feeling proud and without any prior procedure. One of the Serbs in an armed group from Çagllavica, near Prishtina, declared and boasted that in recent events “he had killed 100 Albanians”. (AIHT, 24 October 1913: 2)

In a report sent to the Chairman of the Parliament of the Kingdom of Serbia, Andre Nikolic, on November 30, 1913 by a member of a Serbian armed group, among other things the author of the report declared: “Wherever our army has passed, other people must be sent, because the peopleand everything that belonged to it has completely disappeared”. (Historia e shqiptarëvegjatë shekullit XX, 2017: 452) Consequently, this Albanian uprising served to the Kingdom of Serbia as a pretext for the reconquest of a territorial part of Albania, in order toexpand the “strategic border”, set at the Conference of Ambassadors in London.

To suppress this uprising, the Kingdom of Serbia activated 20,000 – 50,000 soldiers. (AIHT, 25 September 1913: 1; Perlindja, 1913: 6) However, the Albanians could not remain separated and under the pressure of constant violence and military dictatorship imposed by the Serbian and Montenegrin authorities in Kosovo. Therefore, both inside and outside of Kosovo, they were planning to organize another revolt in the spring of 1914. (AIHT, 17 January 1914: 1) Organized in small clandestine groups, they continued to show their revolt through armed guerrilla actions against the gendarmerie and representatives of the administrative power.

At the beginning of 1914, such actions had become so widespread that they began to alert the government in Belgrade that the security situation in the regions of Kosovo was fragile and that restraining steps had to be taken to keep the Albanians under control. (AIHT, 30 April 1914: 2; Политика, 1914: 2) In order to increase the terror and violence against Albanians, the Serbian government in Belgrade organized and brought criminal colonizing elements to the territory of Kosovo, who by joining the Serbian armed groups, led by the chairman of the recruitment committee, Bogdan Radenkovic and members Risto Egnenovic, Griso Elezovic and the journalist David Dimitrijevic, further increased the level of crimes against Albanians. (AIHT, 19 March 1914: 4; Политика, 1914: 1).

According to a report by theAustro-Hungarian Consul General in Skopje, Heinrich Jehtlitschka, on March 31, 1914, which was based on reliable information, among other things it was stated that:

“… Albanians are taken out of their houses at night, sent to fields where there are pits prepared, slaughtered there with knives in complete silence and put in the pit. Women who seek the slain are only told that their husbands or sons have been sent to Belgrade”. (AIHT, 31 March 1914: 2) These destructive Serbo-Montenegrin actions against Albanians, through a report, were also ascertained by the International Commission ofInquiry of 1914. (E vërteta mbi Kosovën dhe shqiptarët në Jugosllavi, 1990: 311-312)

In such unbearable circumstances, the general situation of Albanians worsened, forcing them to organize armed actions against the arbitrariness of the Serbo-Montenegrin violence. The initial center of this uprising was the village of Banja in Malisheva. The uprising broke out in the last ten days of March 1914. Its leaders were Idriz Seferi, Hasan Hysen Budakova, mullah Rifat Haxhihasani, priest Nikollë Gllasniqi, Musa Efendi Prizreni, Sadri Abaz Bytyçi from Kërvasaria, Lush Bajraktari from Astrazub, Hasan KeçëBej from Vushtrri, brothers Fetah and Asllan Laci from Drenoc and many others. They led about 3,000 Albanians in an area that included Drenica, Karadak, Prishtina, FushëKosovë, Fusha e Dukagjinit, Vushtrri, Janjeva, Mitrovica, Pazari i Ri, Senica, Has, Prizren, Luma and Krasniqe. (ASHAK, 14 June 1914: 1; Дедијер & Антић, 1980: 631; Historia e Popullit Shqiptar, 2007: 434).

During the fighting, the houses from which Albanians fired at army troops were bombed and set on fire. The mayor of Prizren, Djordje Matich, blamed the armed Albanians and the families who supported them. In order to justify the operations of the Serbian army, he considered the Albanians “arrogant” and the Albanian population “deceived”. (AIHT, 6 April 1914: 1) According to British diplomatic circles in Belgrade, the military authorities in Kosovo had taken extraordinary measures to suppress the revolt of Albanians with all their might and carried out massacres in the troubled areas to intimidate them. (Duka, 2012: 305)

Only in the Bajrak province of Astrazub, out of 1,380 houses, over 90% of them (1,029 houses) were burnt down and about 300 Albanians were killed and massacred. Among those killed were women and children. There were cases such as in the village of Banja, where the injured were buried alive. As a result of the army’s fierce response, the disproportion of combat and numerical forces, most of the armed Albanians pursued by the Serbo-Montenegrin military troops, fled to Albania after being defeated. (AIHT, 6 & 11 April 1914: 2; Braha, 1992: 211).

The Albanian uprisings against the Serbo-Montenegrin rule in Kosovo during the years 1913-1914, echoed both inside and outside Kosovo, proving once again to the Great Powers that the Albanians would not accept the constant weight on their shoulders of a violent regime that aimed their physical, cultural and national annihilation. They proved to have a freedom-loving character and were presented as an alternative of the time for the freedom of Kosovo and its unification with Albania. Meanwhile, theSerbo-Montenegrin military and administrative authorities in Kosovo used the temporary paralysis of the armed actions of the Albanians as a reason to carry out extreme reprisals and consequently to cause the Albanians to lose hope for their future in Kosovo. This was the ultimate goal of the state circles of the Kingdom of Serbia and the Kingdom of Montenegro, to radically change the demographics of Albanians in Kosovo by implementing policies of assimilation, colonization and ethnic cleansing.

Reference

Kryengritjet shqiptare në Kosovë si alternativë çlirimi nga sundimi serbo-malazez (1913-1914). Fitim Rifati. 2020. Journal of Balkan studies. 2021. https://www.balkanjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/JSB-1.-sayi-revize_2-Fitim-Rifati-1.pdf