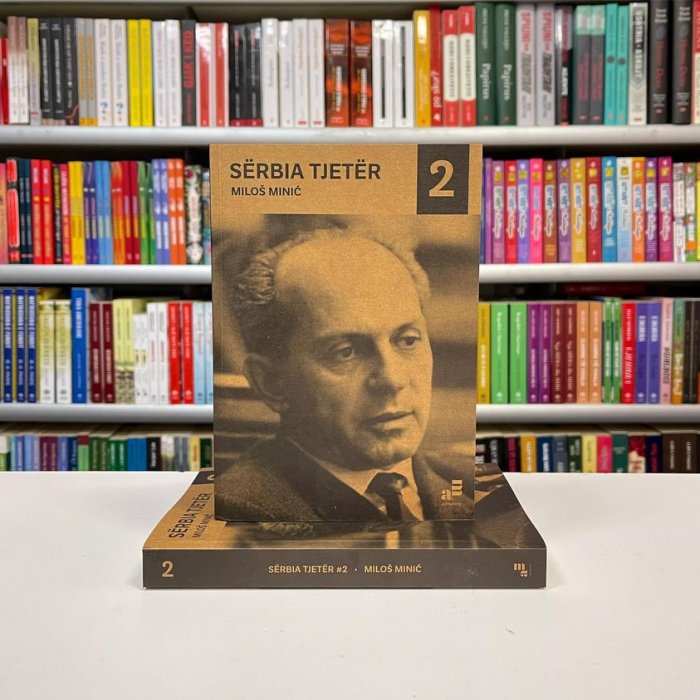

Who was Milos Minic?

He was born in 1914 in the village of Prelina near the city of Çaçak, where he completed his primary and secondary education. He finished his law studies at the University of Belgrade. Since 1935 he was a member of the Communist Youth League of Yugoslavia and then of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. During the anti-fascist national-liberation war, he held party and military posts. He led the negotiations with Draza Mihailovic and his fellow Chetnik fighters, so that they could jointly fight the Nazi-fascist occupiers. After the liberation of Belgrade, he was the head of the People’s Protection Department for the city of Belgrade. He then served as a public prosecutor in Serbia and as a representative of the military prosecution of the People’s Army of Yugoslavia. Minic’s biggest legal case was the “Belgrade Trial”, held in 1946, in which the leader of the Serbian Chetnik movement, Draža Mihailovic, was sentenced to death along with some of his close associates, hence this case is also known as “The Trial of Draza Mihailovic”. Minic held various positions in the Government of Serbia and Yugoslavia. During the 1970s he was the Foreign Minister of Yugoslavia. At this time, he signed the Osimo Agreement for the demarcation of the borders between Italy and Yugoslavia. During the 1990s, he was among the few critics of Slobodan Milosevic’s regime, with special emphasis on his criminal policy against the Kosovo Albanians. He died in 2003 at the age of 89 in Belgrade and was buried in Çaçak.

Minics support for Albanians

The “Other Serbia” project, conceived by Admovere and supported by KFOS, summarizes the positions of Serbian intellectuals who opposed the drastic violations of the human rights of Kosovo Albanians by the Serbian authorities, since the abrogation of Kosovo’s autonomy on March 23, 1989, until to the entry of NATO troops on June 12, 1999, and even later. The violations of this period culminated in the years 1998-1999 with war crimes and crimes against humanity, the murder of about 10 thousand civilian Albanians, the rape of thousands of women and girls, the deportation of nearly a million Albanians, the burning and destruction of about 100 thousand houses, such as and with many other spiritual and material damages.

These intellectuals were inspired by Serbian social democrats such as Dimitrije Tucovic, Kosta Novakovic, Dusan Popovic, Dragisa Lapcevic, Trisa Kaclerovic, and others who, during 1912-13, when Serbia occupied Kosovo, opposed the heinous crimes of the Serbian state against the population of innocent Albanian civilians in Kosovo.

Unfortunately, these crimes were repeated first after the First World War, in 1918-1919, then during the period between the two world wars, at the end of the Second World War (1944-1945), then during the years 1946-1966, and recently also during the last decade of the last century (1989-1999). In this publication, the second in a row of the project, the articles of Milos Minic [1914–2003] are summarized. From the introduction, Minic lists with precision, clarity and correctness, the main historical events with an impact on the relations between Albanians and Serbs, since the Balkan wars of 1912-1913, to continue with the period between the two world wars 1918-1941.

Minić, who himself was a participant in the anti-fascist national-liberation war in Serbia, says that after the Second World War “the partisan military units and the new government installed in Kosovo committed numerous acts of violence, accompanied by chauvinistic impatience against the Albanians of Kosovo.” . Being a functionary in the Serbian republican and federal bodies, Minic also adds that “in the years 1955-1956, in the ‘action for the collection of weapons’ in Kosovo, carried out by the state security service (UDB), tens of thousands of Kosovo Albanians were mistreated “.

There is no doubt that after the Second World War there was mistrust towards Albanians, which according to Minic was mainly instigated by the UDB due to the entrenched Serbian nationalist and chauvinist attitude and was reflected in the predominance of Serbian and Montenegrin cadres throughout Kosovo. After the “Brion Plenum” in 1966, important changes began in Kosovo, which during the 1970s culminated in the high autonomy of Kosovo within the framework of Serbia and Yugoslavia. With the softening of the political climate, Albanian cadres penetrated into the highest positions in Kosovo, Serbia and Yugoslavia. However, with the coming to power of Slobodan Milosevic in the late 1980s, Serbia abolished Kosovo’s autonomy, killed dozens of Albanian demonstrators, dismissed tens of thousands of Albanians from work, severely imprisoned Albanian intellectuals and political activists.

Minice sees Serbian state terror against Albanians in Kosovo as the main feature of Milosevic’s regime and policy towards Kosovo. In fact, apart from describing it as a regime of repression, police persecution and state terror against Kosovo Albanians, he also compares it to the hegemonic politics of Pasic and the Karadjordjevics. On the other hand, he compares the national movement of the Kosovo Albanians and the non-violent peaceful resistance against the regime to the non-violent and anti-colonial liberation movement of Gandhi in India. Most of Minić’s articles deal with the years 1998-99 in Kosovo.

Since the beginning of 1998, in a letter that Minic sent to Slobodan Milosevic, then President of the FRY, he asked him to abandon the idea of a referendum against the interference of the international community in the solution of the Kosovo issue, because no conflict that threatens the peace and security of other countries cannot be an exclusive internal matter. In the letter, he also warned Milosevic about NATO’s intervention, telling him that he would be forced to agree that Kosovo would gain at least some “special status” within the federation, the same as the status of Serbia and Mali. Black. Minic was convinced that the Kosovo Albanians would not accept anything less, because the unscrupulous ten-year rule of police terror had left serious consequences in their state of mind and in their determinations towards Serbia and Yugoslavia.

In almost all the articles, Minic asks Milosevic to take steps to stop the escalation of the situation in Kosovo and to find a political solution by negotiating with the representatives of the Kosovo Albanians. He considers Serbia’s plans for the solution of the Kosovo issue frivolous and irresponsible, “dialogue” simulations that convince the world public that it is the representatives of the Kosovo Albanians who do not want the issue with “dialogue”. For him, it is frivolous and ridiculous that Kosovo Albanians are considered a national minority referring to barren legal theories, therefore he proposes a special status for Kosovo, of the third republic type within Yugoslavia or even complete independence.

Minić is concerned by the fact that when Kosovo is in question, the Milosevic regime is joined by almost the entire opposition, the Orthodox Church, the Academy of Sciences and Arts, the Writers’ Association, and so on. Considering this, he insists that the democratic forces of Serbia resolve the Kosovo issue, because for the disaster that Serbia is experiencing, the responsibility will not be borne only by the current regime that is driving Serbia into chaos, but also by the democratic forces, if they do not unite to offer a completely opposite solution for Kosovo, despite the regime’s possible accusations of “national betrayal of Serbism”. Minic even goes so far as to say that the moral and political responsibility in the world will also fall on the Serbian people if they cover the politics of the Milosevic regime.

The most extraordinary part of Minic’s writings is the opposition to the cruel actions of the Serbian and Yugoslav police and military forces in Kosovo, in which mainly women, children, the elderly, and generally the innocent Albanian civilian population suffered. For Minic, Milosevic was and remained responsible for everything that was happening in Kosovo during the war: the murders, the destruction, the looting and the brutal and massive deportations of the Albanian civilian population by the Serbian and Yugoslav police and military forces. These, Minic asserts, were aimed “to expel all Albanians from Kosovo and to transform Kosovo into a pure ethnic Serbian province”. He even accuses the international community for the delayed intervention in Kosovo, as before in Bosnia, to stop the crimes.

Minic states that Milosevic, with his policy, has brought the Serbian people to a tragic position to suffer, which he does not remember in recent history, and the neighboring peoples, with whom he has lived together for almost a century in the community the same state, has caused serious and unforgettable wounds, victims, destruction and insults. Therefore, he asks a lot of questions: Why is this tragedy happening to us? Who put us in these disasters? Who bears the political, historical and criminal responsibility for the catastrophe that Serbia and the Serbian people are experiencing? Why is the entire developed world in the West against Serbia and the Serbian people? When will the Serbian people understand that they are going down the wrong and dangerous path and return to the policy that the democratic minority in Serbia is committed to today, which looks further and ahead in order to realize and ensure the vital interests of the people Serbian?

Minic reaches the peak of his opposition to the crimes with the open public letter he sends to President Milosevic after the end of the NATO bombings, on June 23, 1999, in which he also raises important topics for Serbian-Albanian relations: who gave orders for Kosovo to be ethnically cleansed of Kosovo Albanians through deportations and mass executions? Who were the ones who evicted the Albanian families of Kosovo from their homes, giving them ten minutes to grab the most necessary things, looting their property and houses, burning the latter in their villages and towns, destroying their burned the villages and settlements, destroyed their personal documents so that they would never return to Kosovo?

The “Other Serbia” project not only offers models of intellectuals who oppose the injustices and crimes led by ‘compatriots’, regardless of their reasoning, but also honors the intellectual who thus often puts his own life in danger, proving an amazing courage that never should not go without the gratitude it deserves. Unfortunately, the Serbian people have seen these personalities as traitors and have prejudiced, tarnished, anathema and attacked them, while the Albanian people have seen them mainly with distrust and therefore ignored them.

Journalists, political analysts, and civil society activists who deal with Albanian-Serbian relations will benefit from this publication; politicians involved in negotiations aimed at normalizing these relations; students, academics, and the general public, including future generations in Kosovo, Serbia, Albania, the Balkans, as well as those interested anywhere in the world, since the publication is also available online and in English, in addition to Albanian and Serbian.

Post-war Kosovo does not have a street named “The Other Serbia”, the alleys branching from which could bear the names of Serbian intellectuals who opposed the occupation of Kosovo, and even supported its independence. Therefore, these publications within the “Other Serbia” project, published by Admovere and supported by KFOS, are a modest acknowledgment of their contribution to the protection of the rights of a of the Albanians of Kosovo, as well as the contribution they made towards the peaceful and friendly separation of the Albanians with the Serbs, but also their coexistence on the basis of tolerance and mutual understanding.