Taken and translated from academic Mehmet Krajas publication “SERBIA’S DESTABILIZING GOALS IN KOSOVO AND THE WESTERN BALKANS“, published on January 24 2022.

According to Kraja, anthropogeographist Jovan Cvijiqi was the one who, after the Serbian invasion of Kosovo in 1913, Serbianized most of the toponyms in Kosovo and, in turn, would define the “Serbian” spaces of this battle, placing these spaces around the tomb of the Sultan Murat. It seems that the Serbs themselves will not have taken these toponyms so seriously for a long time, because it took until 1954 for a memorial to be built on the hill called Gazimestan in memory of the Battle of Kosovo, for whose presence they were remembered only when Milosevic had to declare war on all the peoples of the former Yugoslavia from that “mythical” place. In general, the Serbian myth about Kosovo has never functioned as a corpus of cultural, historical or religious values, but, depending on the circumstances, it has been used politically to promote the nationalist mobilization of Serbia and Serbian chauvinism towards other peoples. The frustrations of Serbian nationalism over this myth have caused Kosovo great tragedies, like genocide.

“In the case of Kosovo, it did not happen, as usual, that a historical event became a myth, but the opposite: a mythicized event turned into history. The Serbian myth of Kosovo has been triggered by a historical event that has not been illuminated in all its components. Even without this mystification, the period of the Middle Ages in Kosovo is extremely dark, with large gaps in the historical memory, filled mainly with legends, despotic rule, church chronicles and trade relations of Ragusan or Venetian origin. Therefore, the Battle of Kosovo of 1389, viewed from today’s perspective, happened as much in reality as in the fantasy of a nation prone to myths and mystifications, making the leap from real events to religious fiction.

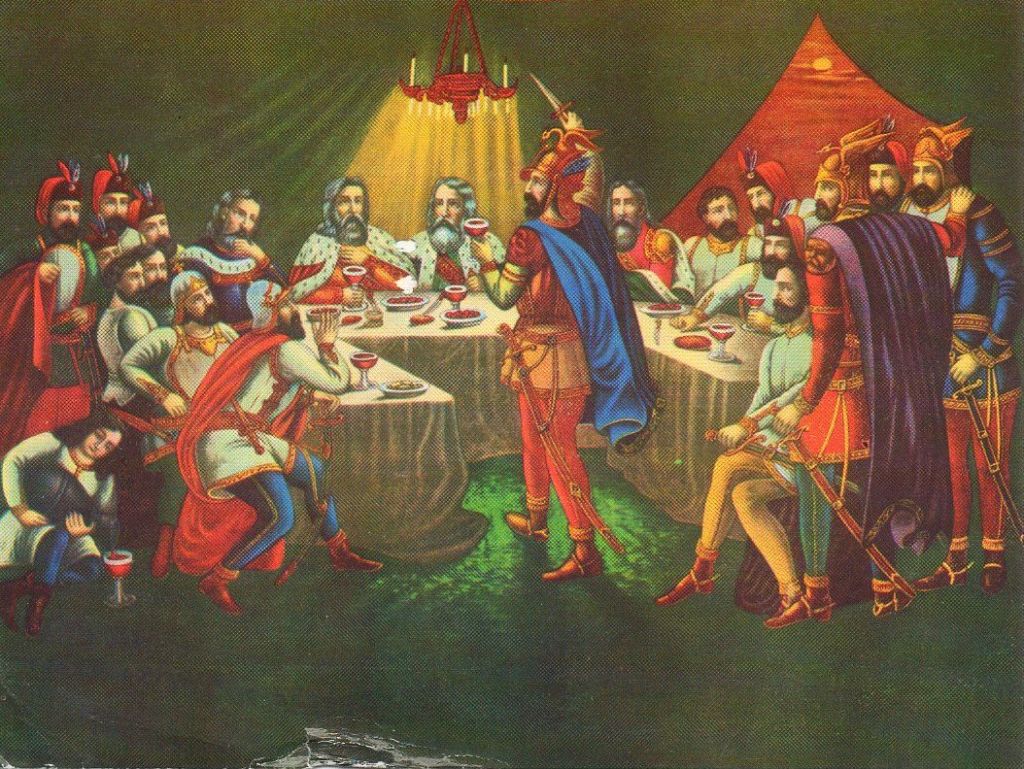

This has generally happened with the knightly epics of the Middle Ages in Europe, including a widespread literature, which Cervantes stigmatizes in his “Don Quixote”. There is almost no difference between the exploits of one of the Serbian heroes of the Battle of Kosovo, Marko Kralevic, let’s face it, and the heroes of Cervantes’ literary fiction. At the time it happened, the Battle of Kosovo was not a match of civilizations, as was explained later, nor a match of two worlds, or of two religions, but a match between an invading army and another defending army; a confrontation of a weak coalition with the army of a great empire, which had achieved great successes in the East and was now at the mercy of Europe.

Before the Ottoman Empire, all great empires, from Alexander the Great to Genghis Khan, made such warlike excursions between Europe and Asia and vice versa. The Turkish chroniclers of the battle were the first to give the religious color to this military confrontation of the Middle Ages, whom the Christians who fought in front of them called “infidels”.

However, the European religious attributes the Battle of Kosova took on later, when Europe was threatened not by an undefined oriental civilization, but by a latent and quite real danger, by a powerful empire, which was almost two steps away from the citadels of Europe. Therefore, it is unlikely that the Balkan coalition functioned as a Christian coalition, for the reason that these countries had already experienced a religious division, that of the division of the churches, which often led to open conflicts and made them unstable ties between peoples through religious faith.

Meanwhile, the selection of Kosovo as a battlefield was determined by the lines of communication, the roads, the territory, the relief, which means that it was a suitable space that communicated without relief obstacles from the East to the West. The line of penetration through Kosovo was one of the three routes, which the Turkish army has continuously used for its expeditions towards Europe.

The versions of the description of the Battle of Kosovo by chroniclers and historians are different, often such that they exclude each other.

However, the Serbian version remained the most widespread, despite the fact that it is also the most disputed. The Serbian myth about the Battle of Kosovo was built on the vague popular memory, carried in the form of legendary epic songs until the 19th century, when romantic ideas dissolved the poetic structure of the event and built a supposed historical reality from it. The process is already known: Vuk Karaxhiqi collected several songs for the Battle of Kosovo and introduced them to European circles, where a tremendous passion for folklore and tradition had already begun. The songs were liked and appreciated with the highest attributes: Goethe and Kopitari highly appreciated the Serbian epic about the Battle of Kosovo, while the Serbian romantics of the 19th century, encouraged by this appreciation, turned the redesigned legend into a national myth.

The Serbian version of the Battle of Kosovo will also be helped by the Turkish version, which has so many inaccuracies about the location of this event that it has created a very suitable space for the mythical Serbian version to build a topography of the event according to interests political. In the place where the Turks believed that Sultan Murat was killed, in the village of Mazgit in the outskirts of Pristina, a tomb was built.

It remains unclear how the riot happened to be built in this very place, when the Turkish chronicles moved the scene to the east and west by dozens of kilometers. What remained reliable in the Turkish version of the Battle of Kosovo was the killing of Sultan Murat by an “infidel” on the battlefield, then the sultan’s body was embalmed and sent to Edirne, while at the place of the murder, where the dead were buried of him, a tomb was built. It is known that today’s tyrba of Sultan Murat in the village of Mazgit dates back to the 19th century and no one can prove that the new tyrba was built exactly where the old tyrba was. But it will be precisely this tomb, which will serve as the main milestone for the Serbian toponymic configuration of the Battle of Kosovo.”

Over 170,000 Albanians were moved from southern Serbia after the Berlin Congress; 30,000 Albanians killed in 1913, after the Serbian occupation of Kosovo; over 250,000 moved to Turkey before and after World War II; about 11,000 Albanians killed by OZNA and about 5 thousand deported after World War II; over 13 thousand killed and a million displaced in the 1998-99 war, etc., all these genocidal acts on a population that barely managed to make it a million residents many years after World War II.

Reference

Mehmet Kraja, 2022, January 24. “Akademia e Shkencave dhe e Arteve e Kosovës.” Synimet e Destabilizuese te Serbisë ne Kosovë”.