Published for the first time on Wikipedia using a pseudonym in 2020.

Gjon Renesi (1567-1624), known in Italian as Giovanni Renesi, was an Albanian military captain and mercenary. He was involved in organizing spy networks within the Ottoman Empire in support of the Catholic powers of Southern Europe and participated in several wide-scale revolt plans against the Ottomans.

Early life

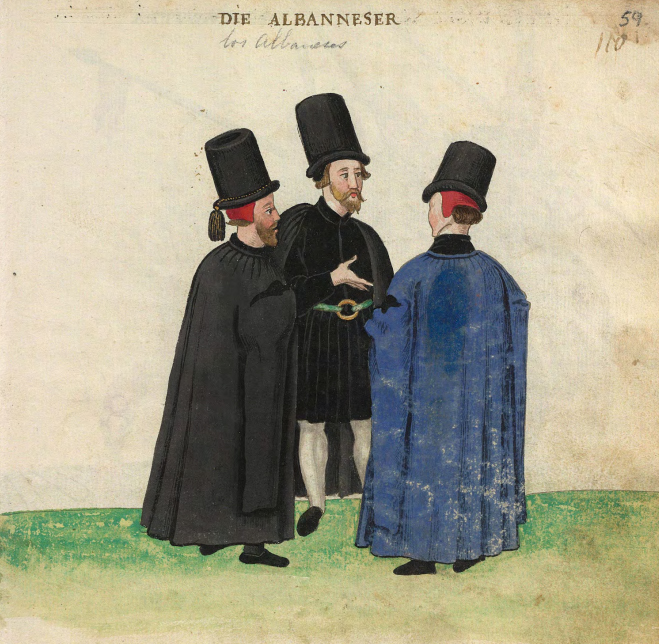

Giovanni Renesi was born around 1567 in the city of Zara (present-day Zadar). He hailed from a Catholic Albanian family belonging to the Renesi clan of Lezhë in Northern Albania. They had settled in Zara as refugees after the Ottoman conquest of Albania and joined the Venetian stradiot regiments like many other Albanian refugees in Dalmatia. His family had produced many military captains, administrators, and governors in the Stato da Mar. Both his father and brother were military commanders of the Republic of Venice. Renesi served the Republic of Venice as a stradiot until 1607 when he was expelled by the Republic of Venice for blood feud killings. After these events, Renesi regularly informed the Venetians of his future activities, perhaps hoping they would lift the ban imposed on him. A Venetian report in the years 1617-18 described him as a man with a pale complexion who had a weak body, a black mustache, and dressed in the “French style” (alla francese).

Rebellion and espionage

In early 1607, Renesi was in Turin and met with Carlo Emanuele I of Savoy. He proposed to the duke to participate in a rebellion against the Ottoman Turks, which was promoted by Duke Grdan of Nikšić and Patriarch Jovan II of Peć. Towards the end of 1607 and the beginning of 1608, Renesi participated in a mission to Mljet, led by Carlo Emanuele, who sent spies to the island and to Ragusa with the aim of supporting the rebel leaders who had gathered in order to oppose Ottoman rule. Renesi’s role was to negotiate directly with potential rebel leaders.

By the end of summer 1608, Renesi arrived in Dalmatia with the emissaries of Carlo Emanuele and informed Grdan of the duke’s decision regarding their previously planned rebellion. Carlo Emmanuele secured his support for the rebellion for the months of January or February 1609, depending on weather conditions. However, the intervention declared by Carlo Manuele for January-February 1609 did not take place, and the duke lost all interest in the Balkans. Renesi, together with other representatives of the rebellion villages, were forced to seek support from another prince, the Duke of Mantua, Vincenzo I Gonzaga.

Renesi arrived in Mantua at the end of 1609, accompanied by a Dutch merchant and two nobles from Ragusa. They presented the plan to the duke and informed him that Maurice of Nassau also wished to participate. Negotiations with the Duke of Mantua dominated until his death on February 18, 1612. Later in the same year, Renesi went to Milan to propose another governor, Marquis de la Hinojosa, the undertaking of the rebellion in Montenegro and Albania. Renesi tried to persuade the duke by offering, in case of victory, two of the region’s most important bastions. Hinojosa encouraged Renesi to go to the courtyard of Madrid as an ambassador of the Albanians and Serbs.

Renesi sent a letter to the bishop of Vigevano in Lombardy, who forwarded it to the Spanish court in Madrid, where Renesi sought military support for the rebellion.

In 1614, Renesi was in Parma to propose Duke Ranuccio I Farnese to take the lead in the rebellion. Farnese sent him money to the Balkans. On July 14, during the Kuči Convention, Renesi informed the local leaders of the Duke of Parma’s support for their plans, and they agreed to recognize Farnese as their lord. These plans were abandoned when he returned to Italy as internal European conflicts halted any plans for a future campaign against the Ottoman Empire.

In August 1615, the Ottoman pretender, Sultan Yahya, and the Duke of Nevers met in Paris. Renesi was also present, and Sultan Yahya gave him a decree addressed to the archbishops, nobles, and leaders of the Balkans. In the decree, Renesi was presented as the ambassador of Sultan Yahya and authorized to negotiate on his behalf. The Duke of Nevers gave Renesi a passport allowing him to travel freely. Renesi left Paris in April 1616, with orders to meet with the dukes of Tuscany and Mantua before going to the Balkans.

In 1617, at Farnese’s request, Renesi went to Madrid. Farnese ordered his ambassador to Spain, Flavio Atti, to meet with the Duke of Lerma, Secretary Antonio de Aróstegui, Marquis de Hinojosa, and the king’s confessor, Felipe II. During the meeting, Renesi told Hinojosa that in the rebellion, there were many regions, and he explained that they were inhabited by Albanians and Slavs, not Greeks. Hinojosa offered to undertake the rebellion in conjunction with Rome and Venice. Renesi argued that undertaking the rebellion would involve the initial costs of both armies and 12,000 soldiers. Negotiations at the Spanish court lasted until the end of October 1617, but no result was achieved.

References

- ^ Groot, Alexander H. de (1978). Uitgaven van het Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te İstanbul (në anglisht). Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut Leiden/Istanbul. fq. 183. ISBN 9789062580439. Marrë më 4 prill 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Floristán 2019.

- ^ Valentini, Giuseppe (1956). Il diritto delle comunità nella tradizione giuridica albanese; generalità (në italisht) (bot. Translation: as in the past, but the strong families of Scutari’s Muslims have influenced to make these flags a group of their own, to them … the last name Rènesi is frequent in C 1416-7; later it is a numerous and very important stradiotic family of which we know very well … Joanne Renesi in 1610 (Biz), and the captains Giorgio and Giovanni Renesi who in the following century made themselves widely known (234) S; …). Vallecchi. Marrë më 2 nëntor 2019.

- ^ a b Bartl 1974

- ^ Biblioteca dell’Archivio storico italiano (në italisht) (bot. Translation: Thus in the summer of 1607, an Albanian captain Giovanni Renesi (already in the service of the Serenissima in Italy and then banished for murder), who had also proposed to Carlo Emanuele the opportuneness and ease of a business in the Balkans. At the beginning of June 1608, according to what the captain Giovanni Renesi himself candidly reported to the ambassador of the Serenissima in Turin Piero Contarini.). L. S. Olschki. 1961. fq. 28–40.

- ^ Studi Veneziani (në italisht) (bot. Translation: Agreeing on the need to obtain the material support of the Italian States willing to participate in the Levantine enterprise, they sent the aforementioned Albanian adventurer Giovanni Renesi, former mercenary, Venetian subject already at the service of the Serenissima and of the Duke of Savoy, Carlo Emanuele 1. On behalf of the latter, the Albanian completed an exploratory mission in the Balkans in 1607, during which also got in touch with the notable secular and ecclesiastical notables of the Dalmatian hinterland. Renesi, who had been banished from the Venetian Republic for murder.). Giardini. 2004. fq. 336. Marrë më 2 nëntor 2019.

- ^ Cuadernos de investigación histórica (në spanjisht) (bot. Translation: Nevertheless, Carlos Manuel had not awakened and insisted on his requests for help in Spain, when a fact came to reinforce his purposes: the arrival in Turin of the Albanian Giovanni Renesi and the solicitor of the Bosnian nobility, Nicolas Drasovich. Both exposed the desire for liberation of their peoples and assured him that, if he helped them, they would rebel against the Turk and recognize him as king. Encouraged by this news, the Duke forged immediately). Fundación Universitaria Española, Seminario Cisneros. 1977. fq. 167. Marrë më 2 nëntor 2019.

- ^ Ćosić, Stjepan (2011). Mavro Orbini i raskol dubrovačkog patricijata (bot. Translation: At the end of 1607 and beginning of 1608, the spies of the Duke of Savoy first visited Mljet and then in Dubrovnik, with the intention of giving financial support to the rebel leaders and organizing supporters among the Dubrovnik lords. Imberto Saluzzio, known as the Commendator della Manta, and Filiberto Provona posed as horse dealers, actually giving instructions to supporters of the uprising and secretly making accurate maps and drawings of the city’s fortifications.13 But another Duke trustee, Giovanni Renesi, who toured the interior and negotiated directly with the leaders of potential uprising groups, he was not impressed by their willingness to seriously resist the Ottomans. Realizing that a good portion of the population did not want to replace “Ottoman tyranny at all with the Spanish authorities”, Renesi reported that the whole venture was based on “very uncertain grounds”. This euphemism was enough to keep the Savoy Duke cool from rapid action and almost give up the whole venture.14). Zagreb: Radovi – Zavod za hrvatsku povijest. Marrë më 2 nëntor 2019.

- ^ José M. Floristán (PDF) (bot. An appeal of the people of Albania, Bosnia, Herzegovina, Serbia and Montenegro to the Spanish king Philip III for military help (1612- 1614). In 1612 the bishop of Vigevano, Lombardy forwarded to the Spanish court in Madrid an appeal for military support he had received through the Albanian captain Giovanni Renesi from the people of Albania, Bosnia, Herzegovina, Serbia and Montenegro for an uprising against the Turkish Ottomans. Such appeal was a continuation of the embassies which had been already sent to several Christian princes in the first decade of the 17th century. Patriarch Jovan II of Peć and the voïvode Grdan of Nikšić were apparently the main masterminds behind this plan.). University Complutense, Madrid). fq. 12. Marrë më 4 prill 2020.