Original publication authored by Pellumb Xhufi. Translated and re-published by Petrit Latifi.

In general, science has accepted that Corfu was inhabited in ancient times by the Illyrian tribe, just like the continent in front of it, until, in the second half of the 8th century BC. e. r. the island was colonized by the Corinthians. However, the geographical proximity of Corfu to the opposite mainland and its inhabitants created such affinities between the two shores of the Corfu Channel, which were also reflected in the composition of the island’s population.

After centuries of Byzantine, Norman-Suevo-Angevin and Venetian rule, from 1570, the bailiff of Corfu, Zuan Mocenigo, reported that the city (borgo) of Corfu was inhabited by about 8 thousand people, of which a part were Albanians, a part were from Puglia and Cypriots, while the rest were born there (da 8 mille anime incirca, parte sono Albanesi, parte Pugliesi et Cipriotti, il resto nasciuti nel loco).

The Albanians, whom Bajliu Mocenigo ranks first, must have been a very important component of the population of Corfu, if we consider that they were “hidden” even among those people, whom he defines as “Puljes”, “Cypriots”. of “born there” (nasciuti nel loco). Sources say that in the century XV, 1000 Albanian fighters were brought to Cyprus, who later left there to settle elsewhere.

In fact, a news from 1550 tells us that at that time Venice transferred 200 Albanian stratiots from Cyprus to Corfu. Many other Albanian Stratiots moved to Corfu after the invasion of Cyprus by the Turks, in 1570. Among them was the knight “dominus Hettor Rhenessi cavallier”. The family of the Renësi stratiots who came from Cyprus established relations in Corfu with another family of Albanian stratiots who came from Pula, with the Muzakaj.

In 1613, the stratioto Gjergj Muzaka is mentioned, who was part of the company of the famous Nikolla Renësi (Zorzi Musachi, stratioto della compagnia del strenuo Nicolo Renessi). But Gjergj Muzaka had other predecessors in Corfu. In 1576, Bajliu Fabio da Canale reported that he had entrusted the defense of Corfu to a guild of 50 stratiotes, whose governor was the knight Muzaka.

This must be the same as the knight Fone Muzaka (cavallier Fone Musachi), who in June 1571, at the head of a select division of knights and about 300 foot soldiers, landed on the shores of Borsh and from there headed for the Sopot castle. In 1571, we also meet the governor Tomaso Musachi, who commanded 65 stratiots, “tutti valorosi soldati et molto fidelissimi”.

A little later, he commanded in Corfu a company of 77 horsemen led by 4 Albanian captains (Captain Albanesi) and a governor named Nikollë Vllami9. It is interesting that these are called “Neapolitan stratiotes”, that is, they were stratiotes that came from the territories of the Kingdom of Naples. This leads us to see in Tomaso Muzaka and his braves the descendants of those Albanians who settled in the Kingdom of Naples after the death of Skanderbeg.

One of them was Gjon Muzaka, captain of Francavilla in 1499. According to Marin Sanudo, this was “son of Muzak Arianiti, once lord of Myzeqe in Albania” (uno domino Zuam Musachii capitano di Franchavilla fò fiol di misier Musachii Areniti fò signor di la Musachia in Albania). He had expressed to the Venetians his desire to go and fight in Albania together with his 300 knights, with whom he promised that he would perform great deeds.

In fact, in 1502 we find John Muzaka as a commander (am iraro) of the coastal city of Brindiz, which at that time was a Venetian possession. The Republic of Venice was at war with the High Port, and the existence of Gjon Muzaka as the commander of the port of Brindiz cannot be overlooked in relation to actions that were expected to take place in Albania.

We do not know the connections between Gjon Muzaka of Brindisi (1502) and another “Neapolitan” Muzaka, Hanibal Muzaka, a resident of Corfu, who is clearly defined as originating from Otrantoja e Pula (Annibale Musachi d’Ottranto). This, before 1580, was married to a Corfiot lady, also the daughter of Albanian Stratiots, Helena Rali. Brindizi, together with the other coastal cities of Puglia, Trani, Otranto, Polignano, Monopoli, passed to Venice after the expulsion of the French armies from Naples by the forces of the anti-French coalition, which arose precisely thanks to the efforts of Venice (1495).

In 1463, an Albanian captain, Mihal Rali, who served for Venice in Elis is mentioned, see: P. Topping, “Albanian Settlements in Medieval Greece: some Venetian testimonies”, in: Charanis Studies: Essays in Honor of P. Charanis, ed. A. E. Laiou- Thomadakis, New Jersey: 1980, p. 267. But the marriage of Hanibal Muzaka and Helena Rali did not go well, as Helena had an extramarital affair with her brother-in-law, Priam Merkuri, who, as was said in Corfu, “se la gode in adulterio”.

But it should be added that the transfer of Albanian soldiers from the territories of the Kingdom of Naples to those of Venice was a continuous phenomenon. As the Venetian envoy, Pier Antonio Zon, reported from Naples on June 6, 1634, many experienced captains who had served the kingdom and who now sought to serve the Republic of Venice appeared to him every day.

Among the Albanians of Venetian Pula was the soldier Marin Dangron, who in 1506 served in the garrison of the Corfu castle and was also married to an Albanian woman.

So, if we refer once again to the declaration of 1570 of the baili of Corfu, Zuan Mocenigo, who claimed that at that time the city (borgo) of Corfu was inhabited by about 8 thousand people, of whom a part were Albanians, a part were Pulje and Cypriots, while the rest were born there, it turned out to us that apart from the “Albanians”, the “Pulje” and “Cypriots” were in a good part Albanian stratiots who came to Corfu from these countries.

Together with many others who had come to Corfu by other routes, the Albanian stratiots formed, since 1435, the main element on which the defense of Corfu was supported.

But, as we will see, even the last category of the inhabitants of the city of Corfu mentioned by Bajliu Mocenigo, that of “born in the country”, i.e. in Corfu (nasciuti nel loco), definitely includes descendants of Albanians who moved from the shores of Albania and who over time were acclimatized and assimilated into the population of the island.

In fact, alongside this Albanian emigration with a military character, such as it was that of the Stratiots, heading towards Corfu without stopping

emigration fueled by various reasons, which were not his alone

economic nature. As is known, some of the rulers ended up in Corfu

the most famous Albanians, who lost their possessions after the invasion Ottoman. On the 19th of June, and even more widely on the 27th of June that year, the Venetian bailiff of Corfu informed the Senate about the fall of possession of Rugina Balsha, the lady of Vlora, in the hands of the Turks.

The troops of Hamza bey Evrenozi had entered the city. Rugina, together with her family and courtiers, found refuge in the Venetian possession of Corfu. Another Albanian prince deprived of his possessions, Gjon Zenebishi of Gjirokastra and Vagenetija (Chamëria), would also end up there after a few years. In Venetian Corfu, John was given a dignified reception. He and his children had been granted Venetian citizenship a little earlier.

On the other hand, in Corfu, Gjoni and his family settled in several properties which he had bought earlier. With the nobility of Corfu, also, John Zenebishi had close ties. Sometime before 1418, John’s sister Maria was married to the Corfiot nobleman Petrotto Altavilla, son of Richard. This, in 1386, had handed over the castle of Butrint to Venice, as well as had helped the acquisition by the Republic of the pier of Sajadha and that of St. Nicholas.

On February 13, 1418, the son of Marie and Peroto de Altavilla, Rikardi, was appointed castle of Parga, with a mandate of 4 years25. It was certainly a choice made with the desire of Gjon Zenebishi, who had a nephew from his sister Richard and had been lord of Parga before it passed to Venice in 1401.

But what left a mark on the life of Corfu was the emigration of the poor. In his Diaries, among the news belonging to April 13, 1501, Marin Sanudo writes that on that day, on the coast of Kasopa, northeast of Corfu, many boats arrived loaded with women and children, who were waiting for their husbands to arrive there together with cattle. The reason for this wave of emigration from Stere was the punitive campaign that was being carried out at that time in the area between Butrint and Saranda by the united armies of the 5 Ottoman sanjakbeylers.

This short announcement illuminates one of the main reasons that historically fueled the waves of Albanian emigration to Corfu and that was the persecution of the Ottoman invaders.

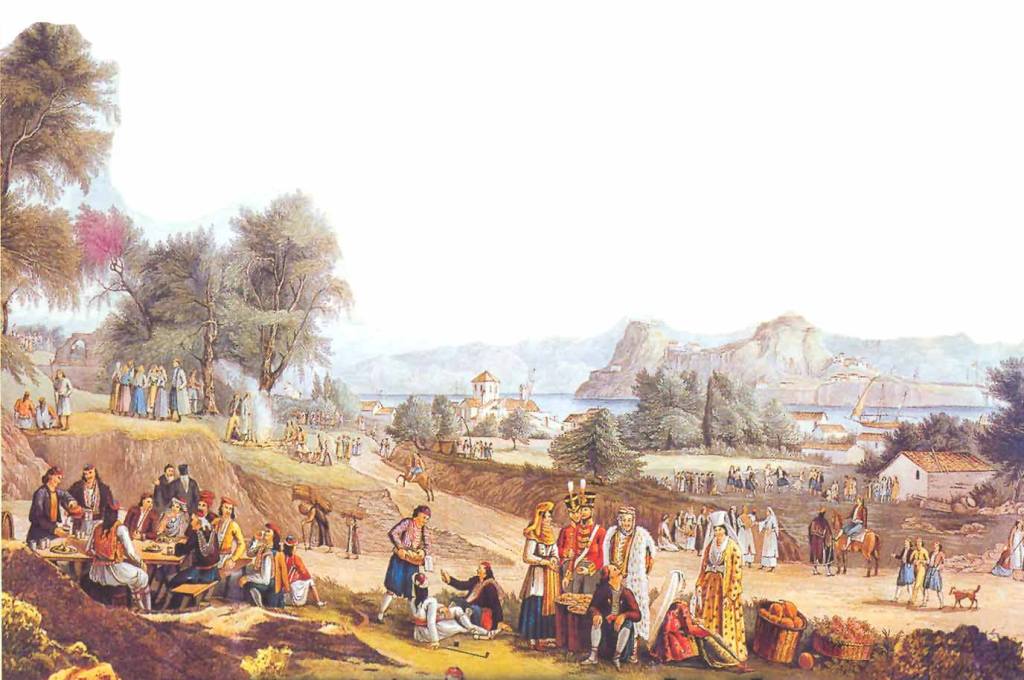

According to the Governor Grimani, in 1616, in the last three years, 4,000 or more Albanians with their families had moved to live on the island, who had brought profit to that country, populating abandoned areas and putting under cultivation deserted. As read in a letter dated October 2, 1627 addressed to the Bajli of Corfu from Qenan Pasha, Vizier and Commissioner of the Sultan Muratit (We, Chenan Passà, Vizier and Commissioner of the multiplying Mr. Sultan Murat), 5 thousand people fled to Corfuz. According to him, many took their families with them.

Qenan Pasha complained that by accepting these Ikanaks on the island, the Venetians had deprived the Sultan of the tribute owed to his slaves. The phenomenon was not unknown to the Corfu authorities, so Bajliu and the Venetian Proveditor-Captain immediately responded to the Ottoman dignitary. “To deny Albanians the right to live on this island”, they wrote, “would mean to affect the freedom that Venice grants to anyone who wants to settle in its possessions”.

After all, the reply continued, as long as every Venetian citizen was allowed by the Ottoman authorities to come, stay and leave whenever he wanted from the “Turkish lands”, it is up to us to do the same with those who come and want. to stay in Corfu. However, to de-dramatize the deliberately inflated news of the Turkish Pasha, the governors of Corfu added that many of the Albanians and Himarjotes mentioned by him were seasonal workers who came to Corfu at the time of grape harvest and planting and after a period of time returned to their homes supporting their families with the money earned in Corfu.

In a word, the Venetians were quick to clarify, such people came to Corfu driven by poverty and not by any feeling of hostility towards the Sultan.

In fact, seasonal workers also came from the Albanian stere, who were used in agricultural work, in fortification works or for the production of biscuits (baking) for the Venetian fleet. The mass of these workers was the most exploited and mistreated.

In January 1558, Bajliu Bernardo Sagredo conveyed to the Senate of Venice his concern, that in that winter season, the Albanian workers wanted to return to their homes due to the difficult conditions and, even more so, due to the fact that they were not were paid. Therefore, he requested that funds be sent for their salary, otherwise they would run away, and in order to return them to Corfu, they would have to be promised a higher salary, as had happened in other cases.

However, the residents of Corfu were not known for tender feelings towards foreigners. At the beginning of the century XVI, Marin Sanudo noted that between the Albanians and the Greeks of Corfu there was “an evil spirit” (è mal animo tra Albanesi e Greci). Such a relationship is also highlighted in the lines of the document of 1411, which speaks of an Albanian emigration to Corfu originating from the province of Vagenetia (Chameria).

The local inhabitants had accepted the newcomers in their village, had given them to work some piece of waste land, abandoned vineyards and orchards, taking them a part of the production. But, at a certain moment, the Venetian bailiwick Roberto Mauroceno decided to recognize those properties as their own to the Albanians and consider them free farmers.

However, a delegation of the Municipality of Corfu, representing the community of its citizens, appeared before the Senate, in Venice, and demanded that those farms, together with the lands, vineyards and orchards donated by the Venetian authorities, be returned to the local inhabitants, as they belonged to them. In a word, it was demanded that the Albanians who came from Vagenetia, not only not be treated as free citizens of Corfu, but be reduced to the category of serfs, since the lands and vineyards were once given for exploitation by the Corfiots themselves, and then donated by Bajliu Mauroceno, would now be considered the properties of the Corfiots and the Albanians would use them, paying the obligations to the locals, who claimed to be their owners.

We note that, in order to maintain good relations with the Municipality of Corfu, the Senate accepted her request, on the condition that the farmers in question and the land worked by them were registered and that they also pay the relevant obligations to the state. Thus, the noose around the neck of the Albanian emigrants was tightened even more. These were declassified overnight, from free citizens, to serfs who owed both their Corfiot owners and the Venetian state.

Despite the often refractory attitude of the local population,

the Venetian authorities did not give up on luring the Albanian inhabitants of stereo to settle with family in Corfu, as part of their program for populating, protecting and bringing the island under culture of Albanian newcomers had created entire villages in Corfu. According to

Proveditor Grimani, in 1616, in the last three years on the island had

4 thousand and more Albanians with their families passed to live there,

to whom the cultivation and flourishing of the entire deserted areas of the island were owed. The Ionian Islands were the ones that most, with different waves, received groups of stratiotes leaving or were transferred from other Venetian possessions.

A number of Stratiots who came from the Morea had settled in 1468 on the islands of Zacin and Cefaloni, which were still governed by the Toco (Tocco) family, vassals of the King of Naples. The newcomers had left with their families from Morea after the arrival of the Turks there. The Republic of Venice relied mainly on these stratiots to seize the islands of Zacint and Kefalonia from the Neapolitan lands, as it first attempted in 1449.

In Zacint, stratiots who came from Italy where they had served the Republic are also witnessed at that time. Such was the stratiot Gjon Kombi (Joni Comi strathiota). Of course, the influx of a large mass of Stratiots to the Ionian Islands was seen with great concern by the authorities and the local population. Thus, on September 28, 1500, the Proveditor of Corfu, Luca Querini, informed the Senate that the fall of Modoni (Peloponnese) into the hands of the Turks, and the news of the migration of the local Stratiots to Corfu, had alarmed the population of the island, who feared that ” even so, there were more foreigners and Albanians there”.

So, to get ahead of everyone confusion that could be caused by the arrival of other stratiotes, the Proveditor requested an additional military force of 200 people. Meanwhile, the range of Albanian stratiots in Corfu is quite wide and includes many other well-known Albanian families. One of these is that of the Buzikis, which in 1495 we find described as “the first family of Albanians” (prima fameglia de Albanexi).

That year, a Nicola Buziki entered the service of Venice in the company of his uncle, Reposh Buziki, stratioti commander “sotto il governo del strenuo Repossi Busichio, suo barba, capo de stratioti”. In 1545, Gjergj Buziki (Zorzi Busichio), who had once served in Nauplion, served in Corfu in the company of his brother, Repossi Busichio. Ten years later, Gjergj Buziki is mentioned together with another Albanian captain, Aleks Kambera, who together with their companies were in charge of guarding the coast of Corfu.

In 1611, Gjergj Skliri (Zorzi Scliri) was appointed captain of a unit of stratiots, who took the place of his brother Nikollë Skliri52. These were, for sure, descendants of captain Llazar Skliri (Lazzaro Scliri), commander of a company of Albanian stratiots, who first distinguished himself in the defense of Sopot castle, in July 1571, and later, on September 10 of that year, he heroically defended Corfu from an incursion by the Turks.

In 1559 there is talk in Corfu of a strenuo Lecca Barbati strathioto, who was appointed governor of the unit of stratiots, which until then had been commanded by his brother, who had just died (quondam cavalliere Barbati suo fratello ultimamente morto governatore della strathia di Corfù). Even Zorzi Barbati was the stratia commander in Corfu in 1597, and after his death, he was replaced in that role by his brother, Spiro Barbati.

Another Spiro Barbati was captain of the Corfu garrison in 1676. But the most prominent of the Barbati seems to have been Nikolla Barbati. In 1655, he was commander of the garrison of Corfu and as such was sent with a difficult mission to Butrint to quell the conflict that had arisen with the Turks over the issue of the annual obligation of local fishermen. In 1661, Nikola Barbati had left the position of the commander of Corfu to his brother, while he appears as the commander of the garrison of Butrint, where he died in August of that year. For his merits, the Senate decorated him with the Golden Necklace. Vincenzo Dorsa says that the family Barbato was among the founding families of Piana degli Albanesi, in Sicily.

The above cases with stratiots from the same family nucleus, undoubtedly speak of a type of family organization, apart from the national one, on which the Albanian warrior guilds relied. In the Venetian registers, the Senato Mar series, for the years 1558-1559, many names of Albanian stratiots serving in Corfu are mentioned. In 1558, Alex Cambiera (Këmbera?), head of a company with 15 stratiotes, was appointed to protect Corfu. In the same year, Stratiot leaders Lecca Barbati, Nicolò Velami (Brother), Dimitri Cuco, Pelegrino Busichio, Pietro Clada, Helia Carma, Zorzi Colossi (Klosi) are mentioned in Corfu. But above all rises the figure of the commander (governor) of the stratia* of Corfu, “il strenuo Dimitri Rali Clada…governor della stratià di Corfù”. His name is often found in the registers in question.

As in More, the fates of Bua and Klada were intertwined in Corfu. Thus, when Paolo Bua died on September 6, 1553, the head of the 20 knights in charge of the defense of Corfu who had come from Nauplion of the Peloponnese, was replaced in that role by Teodor Klada and by Nikolë Klosi (Colossi).

Here is the place to add, that the Albanian military element in Corfu was not only represented by stratiots, but also extended to the war fleet of the island. In 1644, in a list of ship captains, who bear Slavic names and were probably from Perasti, we also find the names of the captains Albanians Gjon Gjoni (Zuanne Gioni) and Ilia Bixhili (Elia Becili), who commanded two Venetian galleys.

Regarding the situation of the Albanian Stratiots settled in the Ionian Islands, and especially their connections with the places of origin in the Albanian stere, it is worth quoting a historical note from Kefalonia from 1637, published by K. Sathas. “When the Turks took Morena”, it is said there, “all the Albanian stratiots (Albanezoi) in the service of the Lordship, came to the island of Kefalonia and Corfu, and the dogge was granted a fief to stay there to guard it.

Buat received fiefs in Menagides in the castle. After a while there was a call from the Turks, that all the Romans who had fiefs should become Turks (Muslims) and take them, otherwise they would lose them. Then, from Buat came Griva and from Spatat Barkezini, who went to Ioannina where they became Islamized and took the fiefs of their families. Griva became cernid (armatol) in Xeromeri, and Barkezini in Himare, taking the paternal estates.

The rest of the family remained in Cephalonia as Christians, and received florins annually from those who converted to Islam. Later, Griva took the gold only to his brother Sguro, and Barkezini to Polikalla. The others got angry and Golem together with Bua and Spata came out and went to the Turk and grabbed the fiefs of his cousin, Grivë. But this one, smarter, killed the last two and took the Golem prisoner.

The Albanians of Kefalonia came out and killed Griva and appointed his nephew, Apostol Bua, but the Turks did not accept him, because he had not become a Muslim. Barkezin’s son, with the help of the Turks, came down from Himara and conquered Xeromer and Vonica and killed Apostoli, his cousin…”.

The above case shows that many of the Stratiots settled in Corfu had not severed their ties with their birthplace in Lower Albania, where they had their history and properties. If many of them from the Zenebishi, Muzaka, Spata, Bua, etc. families agreed to remain or return to their ancestral possessions, converting to Islam, many others, like the author of the Muzaka family genealogy, hoped until end up returning there as victors with the armies of the Christian sovereigns of Europe.

But, certain individuals, left Albania in time and for various reasons, returned to their hearths simply to live. This happened especially in the “free areas”, such as Himara, where the weight of the Ottoman power was felt less. Thus, in 1611, a “Corfiot” is mentioned, Gjergj Grapshi (Zorzi Grapsa da Corfù), who had been living in Dhërmi for several years, where he was also married (ma però habitante a Drimades, dove disse essersi maritato).

But, it is clearly a matter of a return to the homeland, since Grapshi was a scumbag. There were strong connections as far as Vlora with the Ottoman officials of that country. That year, the family members of a person from Budva captured by Vlora pirates entrusted him with the task of negotiating his release, since Zorzi Grapshi “knew how to get along with the Turks” (sà trattar con Turchi).

A Teofil Grapshi, also from Dhërmi and probably a relative of Zorzi, in 1612 informed the Venetians about the Ottoman fleet stationed in Vlorë

In addition to the Albanian stratiots sent to Corfu, as we saw, from Cyprus, the Morea or from South Italy, other Albanian stratiots who served in Corfu and the other islands of the Ionian Sea were sent there directly from the Albanian coast.

Nikolla Borshi, son of Lekë Borshi, the stratiot commander who occupied the fortress of Strovil on behalf of Venice, belonged to this category. On February 21, 1510, he was appointed controller of the customs of Corfu. Such elements moved to Corfu, constituted the link that naturally connected the island with the island in front, where they occasionally went for personal work, but also to carry out missions entrusted to them by the Venetian authorities.

In 1531, the Venetian governor of Kefalonia praised the services of an Albanian stratiot, who had a Muslim cousin, Suleiman, a soldier of a Christian dignitary named Merkur, who was very powerful in the coastal areas opposite the island73. Apparently, the Albanian stratiot was conveying to him interesting information that came to him from his relatives in Albanian Epirus.

In 1558, a “Corfiot”, Dhimo Liani, went by ship to Himare, where he met his cousin, Andrea Despoti, who gave him a series of data regarding the new sanjakbey of Delvina, which Liani forwarded to the Venetian authorities of Corfu.

Equally appreciated by the authorities of Corfu was the captain of the Stratiots of that island, Nicoll Scliri (Nicolo Scliri), who in January 1609 had gone to his village, Shale di Delvina (Salisei territorio di Delvino). Apart from understandable personal and family reasons, his visit also had a discovery mission. In fact, upon returning to Corfu, Skliris reported to the superior authorities on the data he had collected from some Muslims, known to him (diversi Turchi miei conoscenti).

They had just returned from Constantinople, where they had also learned about a 20-year truce that the Sultan had signed with the Habsburg Emperor. In 1506, the Albanian corporal, Nadalin (uno caporal nominato Nadalin Albanese) also served in the garrison of the Corfu castle. The island’s authorities had not forgotten to note in his “file” that Nadalini had relatives in stere (ha parentado in terra ferma).

It should be added that many captains from Himara, who occasionally jumped into their country to recruit soldiers in the service of Venice. Such was the captain Candid Panimperi, who was involved in the 1596 attempts at a major uprising in Himara. This character already resided in Corfu, and therefore sometimes referred to as “corfiot” (Candido Paniperi corfiotto).

But sometimes others, Paniper is distinguished as an “Albanian” (captain Candido Albanese). Dhimitër Basta (Demetrio Basta Albanese), who in April 1616, had undertaken to reconcile a company of Himarian soldiers on behalf of the Venetians, is distinguished from the sources as “Albanian”. Earlier, on May 1, 1608, Dhimitër Basta, who in that case was said to be from Nivica, together with the priest Gjon Klosin from Lukova, were sent as representatives of the Himarjots to Naples, to the Viceroy Count of Benavente.

According to Grimani, the Provost-Captain of Corfu, Basta “had civilized manners, although he was born and raised in a mountainous country, like Himara, among harsh people and more than barbaric customs”81. Dhimitri said that he was from the blood of the famous Gjergj Basta, who fought as a general on the Hungarian front (dice esser del sangue di quel Giorgio Bast, che fù General in Ungheria).

And, according to Grimani, Dhimitri had the merit of having been the first to recruit Himarian soldiers for Venice83. Basta managed to carry out his mission, but the Ottoman commander of the province, Mehmet Aga, upon learning of the departure of Basta and the recruits gathered by him, ordered to burn his house and take the children captive.

However, Basta, who was a man with a sense of smell (uomo accorto), had already sent his family to Corfu, “together with the few cattle” (con alcuni suoi pochi animali) that he owned. Those who came from Stere generally belonged to the lower classes and in Corfu we find them engaged in menial jobs. But there were also elements of the upper classes among the immigrants.

These found it difficult to assert themselves in a hostile environment. Local nobles intervened up to the Senate to prevent the inclusion of Albanian immigrants in the City Council. Venice succumbed to the pressures of the Corfiots and finally decided that the status of “resident” (habitator) would not be given any income, before reaching 10 years of stay on the island.

Surprisingly, in the case of Corfu, Venice behaved differently than it behaved in its other possessions, in Euboea, in More or in the other Ionian islands: there the Venetians created all kinds of facilities to favor the settlement of Albanian Stratiots and their families.

Under the conditions of this pressure from the local aristocracy, the Venetian authorities showed caution in the recruitment of military personnel. The soldiers engaged in guarding the Castel Vecchio and Castel Nuovo, in Corfu, had their personal data scrutinized. Among the Albanian soldiers, those who had the longest period of stay on the island, and who, in some way, were “integrated”, or, even better, “assimilated”, were preferred.

Thus, in 1506, Corporal Pjetër Lanza offered some guarantee to the authorities. In the corresponding tab, which every soldier of the castle garrison had, Lanza’s origin is not defined, as is done with other soldiers. But we know that in 1394, a Lanza, with the title “count” (comite Lanza), ruled near Butrint and Ksamil and was allied with the sebastocrator Gjon Zenebishi.

The passing of the Lanzas to Corfu happened, as it did for many feudal lords Albanians, during the period of the Ottoman occupation. However, the fact stands out that our Lanza, who, even if he had not been born, surely should have decade that lived in Corfu, is not identified like other Corfiots with the determinant “native” and even less “Greek”. It is not identified, really, nor how “Albanian”, as, for example, was described in 1596 by another Corfiot nobleman originally from Himara (captain Candido Albanese).

Apparently, the process of “integration” in the Lanzas of the last century. XVI had advanced, but, as the story of Pjetër Lanza will show below, not so much that to be considered “Corfiots” with full rights. Even more so

proves the example of Pjetër Lanza from 1506. This, clearly, not

was considered “local” and as a guarantee element for service in the guard the castle of Corfu is noted, first of all, the fact that his wife, with whom had two sons, was born in Corfu (nata in questa terra). Anyway,

his guarantee certificate was completed by a “biographical note”, where

Lanza was said to be the illegitimate son of a high-ranking military man

Venetian, of the Captain General, Benedetto da Pesaro. But,

unlike Pjetër Lanza, he did not offer any guarantees for the authorities

In Corfu, the other Albanian corporal, Nadalini (uno caporal nominato

Albanian Nadal).

This was described by his superiors as a “big mess” (molto

scandalous). But this was not his main problem. Nadalini was

Albanian and, apart from being Albanian himself, he was married to a woman with Albanian father and Greek mother (ha una soa moier nativa de padre Albanian et madre Greca). Further still, Nadalin’s superiors seemed to even more disturbing was the fact that he was related to the stereo Albanian, where he also had relatives (ha parentado in terra ferma).

This fact, the last, together with the fact that he did not have a Greek wife, were enough for one day, his commander decided to “give him his hands”, i.e. to remove him from duty (el mi è parse mandarlo cum Dio). Certainly, the desire to maintain good relations with the inhabitants and the local aristocracy of Corfu, prompted in October 1627 the Provost-Captain of Corfu, Lorenzo Moresini, to suggest the removal of numerous Albanian guards (guardia numerosa di genti Albanesi), who were in charge of guarding the castle gates.

In fact, the Albanians were settled there by order of the Senate. But, Moresini noted that in this case he became the spokesman of the Corfiots, the gate guards had the duty to intervene whenever there were fights and fights. And such often happened at the gates of the city, especially among the locals and the soldiers of the Venetian fleet that constantly landed in the port of the city. According to Moresini, the Albanian guards did not give the necessary guarantees to remain impartial in case of such conflicts. On the contrary, since many of them had previously served on Venetian ships, they were inclined to support the sailors against the Corfiots in such clashes.

This negative disposition of the Corfiots towards the Albanians of Stere in this case, culminates in a complaint they presented to the Senate of the Republic in 1536. The complaint begins with a direct accusation against the Albanians of Stere (Albanesi di Terra Ferma), who constantly attacked , both at sea and on land, the Corfiots plundered and enslaved them, stripping them of the little property they had and setting unaffordable prices for the release of the captives.

Well, such things will not happened, in the event that no one from Corfu would be allowed to go to the countries of those Albanians to take salt there and get valanid or other products. It was unacceptable, according to the Korfiots, that such robbers (essi ladri) gave and received with the Korfiots, their victim, and such a thing was direct encouragement for their exploits.

The Albanians were simply enemies of the Lordship and its citizens, as were the Corfiots: even those, who had not yet raised their heads as such, would join the ranks of the enemies tomorrow. Therefore, the Corfiots insisted, the Venetian state should stop any kind of contact with the Albanians, any kind of trade with them. The Corfiots do not forget to mention the salt sold by the merchants of Corfu to the Albanians of Stere.

They even make an open accusation against the Captain of the castle of Corfu, who had permission from the Senate (and here, an indirect criticism is made of the Senate itself) to sell the salt of Corfu in Himara and other places of the island (il magnifico Capitanio del borgo, having licentia dalla Serenità Vostra de vender il suo sal dove vorà, vien comprato ditto sal et conducessi alla Cimera et altri lochi).

The Corfiots also did not leave without mentioning the valanid, which was bought from Albanian merchants by the Corfiots, a trade that, according to them, should be stopped (in fact, it competed with the Corfiot valanid. But, it is noticeable that they do not include grain in the list of “prohibited products”, much less they do not talk about the interruption of the Albanian grain trade, which also occupied the main volume of trade between the two coasts and which provided the bread of the population of Corfu for most of the year.

However, what stands out in this Philippic of the Corfiots is one

deep feeling of enmity towards the Albanians (Albanesi inimici), who they try to demonize them not simply as “enemies of the Corfiots”, but as “enemies of the citizens of the Lordship” (nemici de suditti della Serenità Vostra). It is clear that with this, the Corfiots sought to implicate the Venetian state in the problematic of their relations with the Albanians. The request of the Corfu community, therefore, aimed to model the relations of the Republic with the Albanians of Stere according to the interests of the aristocracy of Corfu.

But the Venetian approach could not be the Corfiot one. The Albanians could not be declared “enemies of Venice” as simply as the selfish Corfiot aristocracy could declare them “enemies of Corfu”. Therefore, the Senate decided not to respond to the request of the Corfiot community, until a second moment (si le risponderà ad altro tempo). It was an elegant way of saying that the matter should not be touched upon again.

Even the decision taken under the pressure of the representatives of the citizens of Corfu to exclude the Albanians from the command posts in the possessions of the Republic in the Albanian territory, the Venetians did not always implement it. Thus, in 1560, Bajliu and Providotre Venetian editors appointed as captain of Parga, with a 5-year term, the head of the Albanian stratiots, Hektor Bua, who a little before had come to Corfu from Zacinti. Hektor Bua continued to be in this position in 1565. A little later, in 1572, the famous Pjetër Lanza, son of Gjergj Lanza, who had performed that duty in the 1540s, was appointed as governor of Parga. an Italian captain, Angelo Paradisio da, was placed under Lanza’s orders Nocera, and 20 Albanian soldiers (vinti Albanesi.)

A few years later, Captain Paolo Capadoca, stratiot, probably Albanian, from Nauplion of More was appointed as governor of Parga. But his appointment greatly irritated the Corfiots. One of their representatives, on December 10, 1582, presented a complaint to the Senate, with which they requested the dismissal of the governor100. According to them, he had served as the secretary of the “traitor” Pietro Lanza, when he was the governor of Parga (1572-1574).

Moreover, Capadoca was not a Corfiot, and his appointment contradicted the Senate’s provision of 1511, which stipulated that the governors of Parga and Butrint should be chosen from among the Corfiot citizens. Capadoca, they claimed, did not have the status of a Corfiot citizen, even though he claimed to have completed 5 years of residence in Corfu.

Even his request to be elected to the Council of the Municipality of Corfu was rejected by a majority of votes by the members of that Council. On this occasion, the Corfiot representatives expressed to the Senate, the “shock” that such an appointment had caused in the hearts of the Corfiots, “which undermined the honorable citizens of Corfu, and appreciated a man who did not deserve such an honor for a number of reasons, which we do not want to mention out of courtesy”.

However, the Venetians continued to appoint “foreign” elements, Albanians or Italians, as governors of Parga. Even on the island of Corfu itself, the Corfiots persistently demanded the exclusion of Albanians from public duties. In February 1443, the Corfiots complained to the Senate that foreigners, especially Albanians, sat in the meetings of the City Council, and demanded that 50-70 people of Corfiot origin, Greek or Latin, or married to Corfiot women, be elected to that Council.

Apparently, the Venetian authorities tried to somehow “soften” this steadfast attitude. After all, in Corfu or elsewhere, Albanians were an important element in Venetian projects. Over time, access to the City Council was liberalized beyond all limits, until in 1565, the Corfiots demanded the reinstatement of the rule that prohibited “Albanians” and “Cephalonians” from entering the Council without fulfilling the following conditions with: 10 years of residence in Corfu, as well as evidence that in their country the candidates had enjoyed the status of citizen (cittadini).

Venice succumbed to the pressures of the Corfiots and finally decided that the status of “resident” (habitator) would not be given any income, before reaching 10 years of stay on the island. Always under the pressure of the Corfiot community, in 1610 the conditions for inclusion in the City Council were further aggravated. To enter the Council, you had to have both your father and your grandfather from Corfiot, so several generations of stay on the island were required!

Practically, this norm excluded Albanians and other foreigners from participating in municipal bodies and offices. Thus, on the basis of these changes, on May 3, 1618, the Proveditor-Captain of Corfu, Daniel Gradenigo, informed the Senate that a representative of the city had asked him to oppose the request of a certain Sguropulli (Sguro’s son) to be admitted to The municipal council.

The Venetian governor claimed that he was forced to fulfill this request, along with some other requests of the Corfiots. A document from two years earlier, 1616, tells us more about the personality of this character. There we learn that Sguropoulli was the commander of a company of 70 footmen, a part Himarjoti, and the rest from the country of Paramithi, all Albanians, strong men (contado di Paramithia, tutti Albanesi, buone genti).

Needless to say, Sguropulli himself (Sguro’s son) was also Albanian.

Despite the austerity measures against foreigners, always taken on the basis of the demands of the nobility of Corfu, they were destined to weaken whenever the island was in difficulty and not only the Venetian administration, but also the Corfiot municipality was in a strait of money. Thus, at such a moment, at the height of the Veneto-Turkish War for Crete, in February 1659, the municipal council of Corfu, on the initiative of some nobles, proposed to accept as citizens of Corfu the members of three families, which in return they had to pay 800 ducats each to the public treasury. In that case, the proposal was unanimously approved!

It is worth investigating here the history of the Lanza family, which had made a name for itself in the history of the two banks of the Corfu Channel from the c. XIV until the last decades of the century. XVI. Vladimir Lamansky considers them Albanians (l’Albanais Piero Lanza). In fact, the data show that this family had its origin from the Albanian Stere, from where it had moved to Corfu at the beginning of the Ottoman occupation.

In 1394, there is talk of “count Lanza” (comite Lanza), who together with his ally, Gjon Zenebish, had possessions near Butrint. Both Albanian lords had undertaken at that time to contribute with rent and 40 master masons for the fortification of Ksamil, which was under the jurisdiction of the Venetian Butrint. This Lanza count must be the same with Gjin Lanza, who at that time was counted among the Albanian nobles “recommended” by the Republic of Venice.

With the Ottoman occupation, like many other nobles of the island, the Lanzas settled in Corfu and very soon they were distinguished and appreciated by the Venetian authorities of the island. The spears appear again in the first half of the century. XVI, already as noble citizens of Corfu. But, as we showed above in the case of corporal Pjetër Lanza, their integration into Corfu society had not been easy. Meanwhile, in one way or another, the Lanzas continued to maintain strong ties with the Albanian stereo.

This was a strong reason why, in August 1499, one Andrea Lanza, the son of the vice-commandant of Corfu, was appointed as castle of Parga (Andrea Lanza, castelan à la Parga fiol dil vicario di Corfù). In fact, the history of the Lanza family, throughout the century. XVI, is closely related to events and characters of Lower Albania. Even a century later, in 1660, in Corfu, the exploits of marked by the captain of the Venetian castle of Parga, Gjergj Lanza, when Parga was surrounded by land and sea by the Turks.

On October 7, 1538, in evaluation of the contribution of heroism shown by him in defense of Ksamil and had come to the conclusion that the fortification works required at least 1 thousand gold ducats, which is why the help of Zenebishi, Lanza and other potential lords was welcome

to the castle of Parga, the Senate of Venice appointed Gjergji captain of Parga with an 8-year term.

But, while he had very good relations with the Venetians, apparently, Gjergj Lanza did not have such relations with his fellow citizens. In 1542, an embassy of the Corfiot community appeared before the Senate of the Republic and asked it to cancel the decision of 1538, which attributed to Lanza the post of Captain of Parga for the next eight years. At that time, Gjergj Lanza was still halfway through his term.

The representatives of the Corfiot community justified their request on the fact that, according to them, Gjergj Lanza had grabbed the post of Captain of Parga “surreptitiously” (surreptitiously).

In fact, even this time the Venetian Senate was forced to accept the request of the Corfiot representation. Thus, in a letter addressed to the Bailiff of Corfu, on March 22, 1546, Gjergj Lanza protests against the Senate’s acceptance of the Commune’s request to terminate his mandate as Captain of Parga.

Wasn’t he, Gjergj Lanza, the man who responded to the call of the Captain General, Girolamo de Pesaro and, risking his life, ran to the defense of Parga, when the city was abandoned by everyone? Wasn’t it the Senate itself that, appreciating his merits, appointed him Captain of Parga for an eight-year term? Wasn’t it the same Gjergj Lanza who, when Parga was still in ruins and surrounded by enemies, went there with only 25 soldiers, with who protected and restored the castle, returning it to its former state?

Wasn’t he the one who had pacified the Albanians of the surroundings and tied them to Venice (ma anchora hò pacificato et subiugato li Albanesi, facendo mi prestasseno la debita obedientia per nome della prefata Illustrissima Signoria). If things were like this, why should the Senate cut off his mandate based on the slander of some jealous and envious people (per suggestion de invidi, et zilosi).

The above document shows that between Gjergj Lanza, on the one hand, and the Corfiot nobility community, on the other hand, there were clashes, which we can only guess. But, what impresses the most is that in this inter-Corfiot clash, the Venetian authorities take the side of the Municipality, that is, of Lanza’s opponents. As we have shown and as we will continue to illustrate further, this is not the first case that proves such partiality. However, in the case of Gjergj Lanza, the attitude of the Senate and the leaders of Corfu provoked a rift even in Lanza’s own relations with the Republic. This is clearly seen with the vicissitudes of Gjergji’s son, Pjetër Lanza (Piero Lanza figliuolo del quondam signor Zorzi).

If we refer to a letter of scratched by Pjetër Lanza himself, on March 26, 1565, addressed to the Baili of Corfu, his clashes with the authorities of Corfu had started for weak motives (per leggiera causa). Initially, Pjetri had injured a person in Zacin, while he was on duty there under the orders of Captain Zuanne Dandolo. The person in question, after a fight, had hit Lanza with a hu and he had responded by hitting him with a sword (à tempo che mi trovava in servitio del Principe essendo capo con il mag.co signor Zuan Dandolo, et appresso per leggiera causa cioè per haver fatto question e ferito uno, che con un legno m’oltraggiò al Zante).

For this crime, Lanza was sentenced to galley service for eight years and, since he opposed the decision, not appearing within a month to carry out the sentence, he was declared a wanted person and sentenced not to set foot in Corfu, Venice and four other Venetian possessions (per qualche mia solevatione, essendo stato sotto il Reggimento del Cl.mo signor Agustin Sanuto confinato in galia per anni otto, e non appresentandomi in termine de mese uno m’intendesi bandito da questo luoco, dà Venetia, e dalli 4 luochi giusta la parte).

However, Pjetër Lanza could not bear to violate this court decision, which aggravated his situation: from now on he was forbidden to set foot in all the territories of the Republic! (per imputation de haver rotto i confini fui bandito dà tutte le terre, et luoci della Signoria Nostra).

However, in 1558, a Beno Lanza is mentioned, who together with Manol Mosko and Giacomo da Veggia, were chosen as ambassadors of the community of Corfu to meet the captain of the Ottoman fleet and to deliver him the gifts of the occasion.

After that, Pjetër Lanza settled in Bastia, in the Ottoman territory (il qual essendo ar ad habitar alla Bastia loco de Turchi). From here, his activity is witnessed in a wide area, from the villages of the Sanjak of Delvina, Igoumenica, Pargë and Konispol, to Berat and Elbasan. However, in the same letter, Piero Lanza does not fail to declare his loyalty and love for the Republic of Venice and, in this context, to list a number of actions that he had performed in the meantime in its favor.

Thus, when some Albanian pirates had kidnapped a merchant from Venice and some other Corfiot fishermen, he, Lanza, had responded by kidnapping the sons of the most prominent pirates, which forced them to release the captives. Lanza had also informed the authorities of Corfu in time about two pirate ships, which intended to hijack Venetian and Corfiot ships that were loaded with grain in Igoumenitsa. But, above all, Lanza offered his services to the Republic for the future as well, conveying important information from the Turkish countries, where he was forced to live (e tra questi luoci d’infideli che mi attrovo non manco alla giornata di farli partecipi di qualche aviso che è necesario molto).

Lanza expressed his belief that with these services, the authorities would suspend his sentence for a period of time, during which he would undertake to perform the most difficult tasks, such as, for example, that of cleaning the waters of the Corfu Channel by Albanian pirates from Kudhesi and Qeparoi (di pacificar li pirati Albanesi cioè Cudessei e Clapeniotes che non infestano più questo canale).

In fact, three years later, in 1568, we find Lanza making the Venetian “informer” from the Ottoman territories of Lower Albania. In the letter he started on March 23, 1568 Bajliut of Corfu from Konispoli of the sanjak of Delvina, Lanza makes the confession as follows. During the time, the letter, in Italian, was undoubtedly written by Lanza’s own hand, as the many gross errors in it suggest. We found the letter in the collection: ASV, CCX, Lettere di Rettori: Corfù, b. 292 (1561-1599): letter started by Konispoli i Delvina, March 23, 1568. This is its original text:

“Cl.ssimo et Ecc.mo signor. Gli giorni passati rittrovandome haduna tera nominatta Halibasani lontano de qui dodece giornate ho riceputo una litera da mio frattelo ms. Marin dil che mi scriveva del bonanimo de Vostra Clarissima Signoria et di più mi scriveva da partte di quella che dovese venir el più presto for fino hala Bastia et di pohi havisar Vostra Clarissima Signoria che quela mi farà un salvo de venir de lì et di ciò phase fine havisando V.ra Cl.ma Sig.a come ha dì 28 de pasato vene hel sanzaco de Delvino had una tera nominata Belgrade dil che lo emini pasato cavalcò con moltti cavali et handasimo hal’incontro per fargli reverence dove el sanzaco havingdo me visto ha cavalo con abito cristiano sico dimandò lo emini di me dicendogli ch’io mo sonno dil che lo emini gli dise hel tuto. Et la matina seguente mi a mandato chiamar et quando fui hala sua presencia mi a chiamato hin suha camera solo et mi dise sei da Corfù, replied signor sì. Et poi mi dise he vero che el vostro signor Bahilo ha fabricato una tore hale peschiere de Botrento et hio gli risposi signor non è el vero ma è ben la verità che i pescatori ano fato una caseta de tre pasa ha ciò l’invernata non si bagnano da la pioza. Et di poi mi dise disime la verità quanta hintrada ha la Vostra Signoria l’ano da le peschiere de Botrento et di ciò mi a parso de dirgli cinque cento ducati più o manco et lui si voltò ha me con bruta ciera dicendome why me dici la busia noi havemo per cosa certa che le peschiere give 12 milia ducati l’ano et di poi mi dimandò del nome de Vostra Clarissima Signoria et dela casada et se quela è giovine o vechio et molte haltre particolar rade et di ciò hiho (=io) gli ho ditto la verità et di più quelo mi a parso con verità per nome de Vostra Clarissima Signoria et poi dimandato com havesi havicinato con el sanzaco pasato et hio gli rispose pacifico et lovevolisimamente lui rispose ma cossi volese hidio che ancor noi havicinamo cosi et hio gli rispose per che causa signor lui dise perche el Vostro Signor bailo non mi dara quelo che io gli dimandaro ne tampoco mi la sarà far quelo che vorò e cose che noi saremo hinimici dil che gli risposi signor habiati per cosa certa del nostro clarissimo Bahilo e gintilomo et tuto quelo che cognoserà che non sia hin pregiudicio del nostro principe et al onor suo ve lo darà. Poi mi dimandò se à Corfù sono hasai tagiapieri. Answer signor questo non so poi mi dise como el Gran Signore porta grande amore hal nostro domino Bailo de Constantinopoli et ogni giorno sono ha casa hinsieme, poi ha showed uno plico de letere sealate con samarco et mi dise quando el Vostro Signore Bailo non mi darà quelo gli dimandarò ho hordine de mandargli quiste lettere et se per queste non farà quela voltta sarimo hinimici dil che clarissimo signore per quanto si dice lui ha ordine et comision grande de fabricar Botrento et la Cimara et con ciò fazo fine et umilmente basiandogli li piedi pregando la per amor del nostro signor Geson Cristo et per questi giorni santi che quela voglia hatender quelo cha hin promeso perche si come merita castigo had’uno che casca hagli erori tanto magiormente merita premio, had’uno per lo suo”.

He had been in Elbasan, his brother, Marini, had brought him word that

his request had gained ground and that the Venetian authorities were inclined to forgive his sins, but for this he had to leave quickly for Bastia to find out about the conditions. On the way there, on February 28, Lanza was stopped in Berat, where Delvina’s new Sanjakbey had arrived at the same time.

This was Bajazit Sgurolli (sanzacho di Delvino il Magnifico Baiasit

Sguroli). It was originally from the city of Berat, where two neighborhoods held it time the name of this noble family. We also remember that in the year 1618, a citizen of Corfu, named Sguropulli, asked to be admitted to City council. The Greek form Sguropulli, which we meet in Corfu and since means “son of Sguro”, equivalent to the Turkish form Sgurolli, which e we find in Albania, in the Ottoman territory and which has the same meaning.

According to S. Pulaha, after the year 1520 there are no more Ottoman dignitaries from the Albanian Sguro family, which is denied by the documents of the fund of the Bailiffs of Corfu. See: Selami Pulaha, Feudal ownership in Albanian lands (XV-XVI centuries), Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Albania, Institute of History, Tirana: 1988, p. 77. Pëllumb Xhufi, “Skurrajt e Arbër”, in: Dilemat e Arbër. Studies on medieval Albania, Tirana: Pegi, 2006, p. 75-88.

In the century XIV Sguraj were the first noble family in Berat, and in the c. XVI, two of the rich neighborhoods of Berat were named Sgura. See: A. Alexoudes, “Dyo semiomata ek herographon”, in: Deltion Archeologikes kai Ethnologikes Heterias Ellados, 4 (1891-1892), p. 276; Pierre Batiffol, Les manuscrits grecs de Berat d’Albanie, Paris: 1886, p. 125; Evlija Čelebi, “Sejahatnamesi”, in: Selected sources for the History of Albania, vol. III (1506-1839), State University of Tirana, Tirana: 1952, p. 177.

But let’s go back to the thread of Pjetër Lanza’s story. In Berat, the emin of the city, who was an acquaintance of his, invited Lanza to the ceremony of welcoming Delvina’s sanjakbey. Sgurolli’s attention was drawn to Lanza’s Christian dress (abito cristiano), so he asked Emin who the stranger was. After the “complete” explanations that Emini gave him (lo emini gli dise hel tuto), Sanjakbeu invited Lanza to a private conversation.

First, Sanjakbeu Sgurolli, who apparently wanted to get as much information as possible about the Venetian “neighbors”, asked him if it was true that Bajliu had built a tower in the fishing grounds of Butrint, which would mark a violation of Venetian-Turkish peace treaties. Lanza hastened to explain to the new sanjakbe of Delvina that it was not a “tower”, but a small hut that the local fishermen had erected simply to protect themselves from the winter rains.

To Sgurolli’s other question, how much annual income did the Lordship get from the fishing boats in question, Lanza gave an equally “reductive” and certainly absurd answer, choosing to say that it was more or less 500 ducats (mi a parso di dirgli cinque cento ducati più or manco). Upon hearing this answer, Sanjakbeu turned to Lanza with a frown on his face and warned him not to lie (si voltò ha me con bruta ciera dicendome perche me dici la busia).

“We”, he continued, “have reliable data that 12 thousand ducats are extracted there per year”. Further, in a more friendly tone, Sanjakbeu asked about Bajli’s name, age and family. “This time”, Lanza continues his confession, “I told him the truth” (di ciò hiho gli ho ditto la verità). Next, Sgurolli wanted to know how the Venetians had fared with the predecessor Sanjakbey. “In love and in peace”, was Lanza’s answer, which tended to magnify the positive aspects and minimize the negative ones, which could dispose the new sanjakbe against the Lordship.

“So, God willing, I also want to go with Bajliu”, retorted the Turk, “but I’m afraid that he won’t give me what I ask, much less he won’t do what I want, and so I will we end up as two enemies” (non mi dara quelo che io gli dimandaro ne tampoco mi la sarà far quelo che vorò e cose che noi saremo hinimici). To this pessimistic note of Sanjakbeu, Lanza, who clearly narrates things according to the taste of the recipient of the letter, Bajliu, replied that Bajliu was a noble man and would do everything to please him, provided that the interests of the Republic and the honor of his.

As if to say that there was no shortage of positive examples, Sgurolli, for his part, mentioned the great friendship that connected another Bajli, the Bajli of Constantinople, with the Sultan, who invited the Venetian to his palace every day. Furthermore, Sanxhakbeu had shown Lanza an envelope of letters bearing the seal of Saint Mark, which had been given to him in Constantinople by Bajliu for his counterpart in Corfu.

He had to give these letters to the Bailiff of Corfu, in case he did not respond to his demands. And in the event that, even after the delivery of the letters, Bajliu would not budge from his refusal, then he, Sanjakbeu, would be obliged to treat him as an enemy. And, as Lanza had been able to find out, in such a case Sgurolli had orders to begin the fortification of the castles of Butrint and Himara, which was considered an act of war against Venice, as long as these two castles, based on the peace treaties , were considered “demilitarized”.

Perhaps Sgurolli’s indiscreet question about the number of stonemasons in Corfu was also related to this, a question to which Lanza did not know, or did not want to answer. This was the content of the conversation with the newly appointed Sanjakbe of Delvina in Berat. At the end of the letter, Lanza asks for his sentence to be forgiven, as Bajliu himself had promised him a year ago, when he, with his two boats and risking his life, managed to capture the pirate ship that was damaging the Corfu Channel and kidnap and deliver to the Venetian authorities the children of the Albanian leaders.

On this occasion, and on the occasion of the surrender of an Albanian murderer (dandone hale mane uno Halbanese homicida), Bajliu had publicly promised Pjetër Lanza’s brothers his forgiveness. Therefore, even in consideration of the last service he thinks he did to the Republic by “processing” in favor of Venetian interests the new sanjak-bey of Delvina, as he shows in the letter we have just elaborated, he demands that his word be kept and he should not remain a wretch “deprived of his homeland and of the opportunity to serve the Republic” (come son dismenbrato dala mia patria et dela servitù de l’illustrisimo principe).

It is difficult to determine to what extent Piero Lanza was telling the truth in his letter to Bajli Lorenzo Leonardo. It is also undoubted that in that letter, Lanza also conveyed messages from Sanjakbey Sgurolli and his role, thus, can be considered that of a double agent. However, bailiff Lorenzo Lenardo, in a way, was convinced or moved by its content and especially by Lanza’s fervent pleas to forgive him the sentence.

Therefore, on March 27, while forwarding it to the Senate Piero Lanza’s message, he accompanies it with a cover letter of his own, where, after underlining the good behavior the deportee had demonstrated since he was sheltered in Bastia, in the Ottoman territory, he expresses the opinion that Lanza deserved mercy. At the very least, he deserved to be granted a temporary residence permit, during which he would have the opportunity to perform good deeds, becoming an example for others.

Only four months passed, and in July 1568 Piero Lanza performed another service, the last, in favor of the Venetians. Upon hearing that the Ottoman fleet had departed from Constantinople towards the Adriatic, he proposed to the Venetian leaders of Corfu to infiltrate the Turkish ships in order to gather information about the fleet’s intentions and convey it to the Venetians (penetrar sino dentro la ditta Armata, et ne avisa).

In fact, Lanza arrived in Preveza, where the Ottoman fleet had meanwhile arrived. He managed to count about 100 ships, five of which set out on a reconnaissance mission towards Pula. He also learned from local suppliers that large quantities of cement were being loaded onto ships, a sign that a large expedition was planned. As proof of what he was reporting, Lanza also sent a sample of the pastries in question to Corfu (et che verification di cui ne ha mandato mostra de ditti biscotti).

These good behaviors of Lanza induced the Venetians to release him from the serious charges. Already a free man, in December 1570 Pjeter Lanza was in Venice, where he presented a special request to the Doges. After recalling the services his predecessors had rendered to the Republic, Lanza mentions some of his recent deeds in its favor. Thus he mentions the occasion when he gave the Venetians information about the movements of the Ottoman fleet, his actions against pirate ships, his sacrifices even at the risk of life to supply dangerous areas with grain.

Here we learn that Lanza also participated in the fighting for the capture of the Sopot (Borshit) castle, where he had contributed with a pirate ship, equipped with own expenses and with 80 fighters on board.

With one of the Lanza ship and performed other services in favor of the Republic. A few months before the battle of Lepanto, he had landed with two transport ships on the coast of Saranda, where he robbed the local Turks of a large number of horses, which he took to Corfu. Lanza also remembers the capture of three pirate ships in the waters of Zacint, for which he received a letter of thanks from the Proveditor of Zacint and the Bailiff of Corfu, on September 7 of that year.

In the end, Lanza attributes to himself another action, the burning of the village of Agia, which constantly fell on the neck of the city of Parga. After that, he forced this village as well as other surrounding villages to submit to the authority of Venice. After listing all these feats, and after deliberately ignoring the serious problems he had until a moment ago with the Venetian authorities and the fact that because of them he had been a “bandito”, Pjetër Lanza begs to be given the opportunity that with a small amount of money and a few people, he could rebuild the castle of Parga and bring it back under the control of the Republic by cooperating with the rebellious inhabitants of that province.

In doing so, he was sure that many villages that had previously pledged allegiance to Venice, as well as others, would be brought back under his shadow. However, in making this proposal, Lanza did not forget to add that in case this proposal of his was not accepted by the Senate, he was ready to accept any other task that would be entrusted to him and that he would perform with it. the same dedication and selflessness, with which he had served the Republic even before.

Finally, aware of Venetian stinginess, Lanza assures that the small expenses which would be necessary for the operation of rebuilding Parga and re-establishing Venetian authority in the whole province around it would in a short time be drawn many times over from the revenue which would they lived from the products of the surrounding villages, from the mills and from the inhabitants of the villages that he had put under the authority of the Republic and that were about 2 thousand men and that together with their families made 5 thousand souls.

In response to this request, on January 10, 1571, the Senate informed the General Governor of the Sea as well as the governors of Corfu. He explained to them that for the reconstruction of the castle and the peace of the territory approx Parga, Lanza had only asked for 1 thousand ducats and 50 trusted soldiers. The income would come from the obligations of the farmers and the mills of the surrounding Albanian villages.

In the meantime, he himself managed to secure the cooperation of the Albanians who lived around Parga and who shortly before had risen up, “who stood out for their steadfast loyalty to the Republic and on whom he had great influence”. In consideration of these factors, the Senate ordered that proper inquiries be made as to whether Lanza’s proposal was worth carrying out, and if so, that 50 soldiers should be made available to him at a salary of 20 ducats a year, appointing himself as commander of Parga. But, in the event that, based on their information, such a task would seem excessive to the Governor of the Fleet and the leaders of Corfu, Lanza should be given the command of a galley or some other task.

In fact, on January 9, 1572, Giacomo Contarini, Commander-in-Chief of the Fleet, together with the Baili of Corfu, Francesco Correr, decided to send as governor of Parga and the other Venetian possessions in Stere, precisely Peter Lanza (come Governator del detto luogo et di quei paesi di terra ferma sudditi del Serenissimo Dominio). The city’s citadel had been destroyed by the fighting of the previous year, and the population of the surrounding villages had been scattered.

Pjetër Lanza should do what his father, Gjergj Lanza, had done after 1537, when he was also appointed governor of Parga. It was necessary, therefore, to rebuild the walls of the castle, to populate the country by attracting the inhabitants who fled from the horrors of the war of 1571, and to stabilize the situation at that critical point of the Venetian possessions.

For this purpose, 150 soldiers were made available to Lanza, “among whom 20 must necessarily be Albanians” (computando però vinti Albanesi). Furthermore, in the group of people who would accompany Pjeter Lanza in this action of the reconstruction and regeneration of Parga and its surroundings, there would also be an Italian engineer (inzeniero), together with eight masons (mureri) and six carpenters (marangoni ). In addition to them, in the construction works, Lanza had to engage local workers (nelle opere vi servirete nella fabrica plantain huomeni del paese).

But this “reconciliation” of Pjetër Lanza with the Venetian authorities lasted only one year. In 1574, extremely hostile language towards him is encountered in Venetian documents. Peter Lanza was now accused, more and more harshly than ever, of being a bandit banished from all Venetian territories (bandito da tutte terre e luoghi). The Bailiff of Corfu had received a firm order, “to hand him over to give him the last punishment, and if he could not arrest him, to kill him on the spot” (sia preso per darli l’ultimo suplicio, et non potendosi prendre, che sia ammazzato).

An order of the Council of Ten to the proveditor of Zakynthos, June 9, 1574, seems to indicate the reason for this new outburst against the problematic pinyol of Lanza. This harshness towards Pietro Lanza, scion of an old family of the Epiro-Corfiot area, with so many services in favor of Venice, is not explained simply by “transgressing the border” on his part, nor by the undefined “crimes” of his.

The issue was that Peter Lanza, at that time, had been put in the service of the King of Spain. Precisely, on a June day in 1574, at the head of two galleys that had been made available to him by the Spaniards, Lanza had stopped on the shores of Parga, where 4 citizens from Parga, experienced sailors, Domenik Sula, Andrea Perilurgi, Giani (Jani) Nando and Nikola Arilioti.

From here, the galleys were ambushed at the mouth of the Orfio river, in the stere in front of Zaçint, where they abducted a subash and another Turk. Lanza’s actions in Venetian territories on behalf of a rival foreign power, such as the Kingdom of Naples, created implications that went beyond Lanza himself. The case of the kidnapping of the Turkish subash was destined to destabilize relations with the Turks, but also with the Neapolitans themselves, who seem to have been his sponsors.

It was not the first time that Pjetër Lanza worked for Napoli. Even in 1565, supported by Spanish troops and with the participation of the Himarjots, Lanza had captured the castle of Sopot and destroyed it from the foundations. Years later, Lanza would be appreciated by the Venetians as “head of the King’s agents” (capo delle spie del Regno).

As is known, the Venetian authorities resented any involvement of the Neapolitans in the affairs of Corfu and the Albanian coast. Corfiot chronicles of the c. XVI-XVII, are filled with cases of Corfiots, Neapolitan agents or maybe agents, who worked to hand over Corfu to the Spanish. Moreover, when actions like those of Lanza hit, as we have seen, even Ottoman targets or citizens, then serious problems also arose in Venice’s relations with the High Porte.

For her part, Lanza’s killing did not appear to be without problems. It would cause the reaction of the Kingdom of Naples, which he served. Therefore, to avoid clashes with the Spaniards of Naples, the Council of Ten ordered that, unlike Lanza “to whom the law should be applied”, his companions should be treated gently and sweetly, making it clear that such behavior towards they owed it to the fact that they were people in the service of His Majesty, the Catholic King (che non offendano alcuno di quelli che fusse in sua compagnia, anzi li farete accarezar et dire che a loro, come a servitori del Serenissimo Re Catholico overo delli illustrissimi soi the minister siete per far ogni cortesia, ma che verso colui bandito et malfator è stato forza eseguir la giustitia). In this way, Venice eliminated the head of the Spanish-Neapolitan intrigues in the Ionian Basin, while maintaining formal relations with the Spanish.

After all three Neapolitan “agents”, who were in contact with two soldiers of the garrison of Corfu, with whom they had prepared a plan for the surrender of the island to the King of Naples (essergli stato rifferto da un tal Hieremia Lefdi caloiero Zantiote che con Michelis habitante costà, et un papas Retinioto, che oficia pur costì nella chiesa di S. Giorgio di Greci tengono segreta inteligenza con due soldati di questo presidio per tradir à Spagna col mezo di essi questa importantissima piazza).

“Lanza’s actions were also directed against those who use him” (poichè con tal modo fa ingiuria anco alli medesimi principi che se servono de lui).

In conclusion, if the said Lanza was captured in Zacin, he was to be hanged on a rope and if it was not possible to fight him alive, he was to be killed with an arquebus or by any other means (capitando el ditto Piero Lanza in quell’isola, facciate chel sia preso, et subito lo farete appicar per la gola, sì chel muori, et se non si potesse commodamente haver vivo, lo farete ammazzar di archibusada o in altro modo che vi parerà).

In fact, the Venetians had reason to demand the elimination of Lanza. As learned from a letter dated November 2, 1576, that the Himarjots sent to the Viceroy of Naples, the latter had precisely sent “Captain Peter Lanza” together with the Duke of Torre Maggiore to finally destroy the castle of Sopot, which the Himarjots had just captured from them the Turks.

After several years of silence, in 1591 the name of Pjetër Lanza reappears in Naples. At that time, at the head of the Orthodox Church of St. Peter and St. Paul in Naples, the Himarjoti Kurtez Vrana, who had finished his studies at the Orthodox College of St. Athanas, had come. He replaced Akacio Kasneci in that post, also from Himarjot, probably from the village of Vuno.

With the arrival of Vrana, he began a battle against the “errors and superstitions” into which the Orthodox believers of Naples had fallen, seeking their closest possible rapprochement with the Church of Rome. But such a “reform” caused harsh reactions among the Orthodox community of Naples and among Vrana’s opponents, Pjetër Lanza150 is also mentioned. Peter Lanza reappears in Naples in 1594. Before that year he was arrested and imprisoned in Castel dell’Ovo prison and later in Castelnuovo prison.

The Neapolitans accused Lanza of being a double agent of the Turks (doppia spia) and, as was already his style, to prove the contrary, Lanza had sought to take action against the renegade Scipione Cicala, captain of the Ottoman fleet152. In 1596 Lanza was, however, free, and in April of that year he is identified by the Venetian resident in Naples, G. Ranusio, as the initiator of the dispatch of Neapolitan arms to the Himarjotes (questo inviamento è opera di Pietro Lanza), in view of the uprising that Archbishop Athanas of Ohrid was preparing at that time.

Under these conditions, on August 27, 1596, Pjetër Lanza was arrested again by order of the king and put under torture. The reason for this new break with the King of Naples seems to be given by the Venetian resident Ranusio himself, in his report of April 6, 1596: Peter Lanza, under the guise of serving the King of Naples and in agreement with the head of the Himarjotes, had passed through hands large quantities of weapons, which, instead of using them to fight the Turks, they sold them precisely to the Turks, making huge profits.

Such a thing, apparently, if it had really happened, would have reinforced the suspicions of the Neapolitans that Lanza was an agent of the Turks (doppia spia), an accusation raised as early as 1594 and which had cost him the isolation in the castle of Castel dell’Ovo and of Castelnuovo155. However, Lanza successfully passed this last test. As the Venetian resident in Naples reported with a sense of admiration, Lanza had resisted torture for two hours without opening his mouth, so much so that the authorities were forced to release him. In fact, even after that, Lanza knew how to approach the Neapolitan court.

At the time, the king (regent) in Naples was Fernando Ruiz de Castro, Count of Lemos (1599-1601), who organized a veritable state-sponsored pirate activity based in Naples and Sicily against Venetian, Ragusan ships Turkish, severely damaging commercial traffic. Lanza immediately caught this tendency of the young sovereign, and in November 1599, while he was already kept under a kind of “house arrest”, he had managed to fill his mind, to carry out some strong gestures, from arming for the purposes of piracy of the two ships (felucca), which belonged to the queen, until the daring “assassinations” were carried out in the capital of the Ottoman Empire.

With this excessive zeal, he hoped to be freed from the charges and punishment. But, it seems, he had exceeded his goals again, and on September 26, 1600, Lanza is again proven as a prisoner. On May 7, 1602, the Venetians were informed that Pietro Lanza, now free, had met in Naples with Mikel Protetri, a “bandit” (expelled) from Corfu, like himself, accused of numerous robberies and robberies.

The two had left Naples together on board two ships. The Venetian envoy in Naples, Anton Maria Vicenti, reported that the two “bandits” had received permission from the authorities to carry out plundering actions against Turkish ships in the waters of Corfu. But he suspected that they would not let the opportunity escape them to attack any ship they found on the way.Meanwhile, the Venetians continued to follow the actions of Lanza, who for them had been “the head of the King’s agents” (Pietro Lanza già capo delle spie del Regno).

On the way to the sea of Corfu, Lanza together with his partner stopped in Otranto. Here, on June 4, 1602 they tried to stop the departure of a ship to Venice, with which the local Venetian consul sent an announcement to the Senate about Lanza’s mission. In July, in the vicinity of Bar, Pjetër Lanza’s ship attacked and plundered a ship from Budva.

In front of the port authorities he justified himself that the ship was Turkish. The event caused the protest of the Venetian resident in Naples, who demanded the removal of Lanza from that area165. In fact, the king summoned Lanza to Naples, where he appeared in August 1602.

On that occasion, the Venetian resident, Vincenti, expressed the hope that Lanza would be imprisoned and his “persecutions” would end once and for all ( sue male operationi). In fact, in April 1603, Lanza was arrested again. Two months later, the court sentenced him to serve in the galley. But, giving this news, the Venetian resident expressed his doubt that the King would reverse the court decision, locking Lanza in a castle. In the galley, Lanza remained equally dangerous, as he could cause riots among the sailors.

The reason for the punishment of Lanza with service in the galley, this time on the part of the Spaniards of Naples, gives a letter dated February 3, 1606 and an Epirote dispatch to the Viceroy of Naples. Among other things, there was denounced “a certain Greek named Peter Lanza, known as a disturbing person and convicted of forgery by the Viceroy, together with several other Greeks” (un certo greco chiamato Pietro Lanza … homo inquieto et condenato in galera per falsario dal detto regente con altri greci).

According to them, the reason for this hostile attitude of Lanza lay in the fact that the members of the delegation from the Ionian lands had not agreed to include him in the delegation that appeared in Naples.

But Lanza’s pinjolli tried to raise his head once again, and the opportunity for this was given by the newest project of a naval campaign in Albania by the King of Naples.

On July 18, 1606, the Venetian resident in Naples, Agostino Dolce, reported that in one of the 26 ships prepared for a campaign, that the resident in question suspected that he would go to the Albanian coast, Pjetër Lanza had embarked, who was now valued more than Jeronim Kombi himself by the Marquis of Santa Croce (detto Lanza, che col’Marchese prevale a Gieronimo Conte).

The Venetians, once again, returned to the plans for the physical elimination of Pjetër Lanza, and that same year, in 1606, an acquaintance appeared to the Venetian resident in Naples and showed himself ready to kill Pjetër Lanza. But even this project to eliminate Lanza was not realized.

The latest announcement about Pjetër Lanza is worthy of his life full of vicissitudes and adventures. On December 16, 1608, at a time of strained relations with Spain, Paolo Veneziano, Turkish translator to the King of Naples and informer of the Republic, informed the Council of Ten about a secret mission to Constantinople of Peter Lanza. The Venetian describes the adventurer from Corfu at that time as “a man already 75 years old, large and red-faced, with drooping eyelids, with a rough look and with a mouth that was always open, who when he spoke and laughed had he used to rub his white beard”

This old man, charming and scary at the same time, had been serving the King of Spain for 50 years as the captain of scouts who were sent on a mission to Constantinople (a cinquante anni che serve il Rè di Spagna de capitan delle spie che vanno a Constantinople). Now, at the end of his life, he had undertaken to perform the most spectacular and heroic act of his life:

“To sneak into the capital of the Ottoman Empire, infiltrate the arsenal disguised as a Venetian and set it on fire with several fireworks invented by himself. Lanza then planned to enter the city’s two castles and blow them up by igniting the gunpowder crates, which would allow them to be captured with only 100 warriors.”

In the end, Lanza promised that he was able and had enough courage to kill the Sultan himself, posing as a Venetian merchant and presenting him with a wooden box gilded on the outside, which Albanians in Corfu and the case of the Lanza family hid inside a highly sophisticated gun-pistol that, when the box was opened, fired automatically.