Written by Sheradin Berisha. Translated by Petrit Latifi.

On May 26, 1999 The Trimave neighborhood (former Tusus neighborhood) is located in the southern part of Prizren at the foot of the Cvilen mountains. During the war, this neighborhood was the main base of the Kosovo Liberation Army, and played an important role in the massification of the KLA ranks in the Vërrin area, and as such was placed under constant surveillance by the occupying Serbian forces.

In the months of March – May 1999, at a time when Serbian military and paramilitary forces forcibly displaced the Albanian population to Albania, Tususi had become a powerful nursery for the KLA, and therefore most of its residents did not leave their homes, and for a time dozens of families from Vërrin, Opojë and the villages of Theranda and Anadrini even found shelter there.

During this period, Serbian criminal forces have attempted to establish themselves in Tusus several times, but have always encountered armed resistance from two KLA units, the 125th Brigade, led by the commanders: – Samidin Xhezairi – Hoxha and – Zafir Berisha. To “challenge” this invincible resistance of the KLA, the Serbian military command in Prizren, on April 24, 1999, mobilized large military and police forces and surrounded the Tusus neighborhood.

On this occasion, 50 men were arrested and sent to the “Sezair Surroi” sports center, which, with the beginning of the NATO bombing (March 24, 1999), had been transformed into a “large concentration camp” for hundreds of Albanians captured from different parts of Kosovo, who were being deported to Albania. According to multiple witnesses, during April-May 1999, Serbian military and paramilitary forces forced hundreds of captured Albanians to open trenches in several settlements along the border to protect themselves from NATO bombing.

Human Rights Watch interviewed two men who had been taken from their homes on April 24 to serve in labor brigades. They were initially gathered at the Prizren sports center, near the army barracks, and given old army uniforms to wear. They were then taken to the Dragash municipality, south of Prizren, where they dug trenches for a month.

Other residents of Prizren who had abandoned the city in mid-April said that they had left precisely to escape such gatherings… During May 1999, KLA units, protecting the Albanian population, clashed several times with the Serbian occupying forces in the Tusus neighborhood and in other parts – along the Cvilen and Vërrin mountains. The culminating event of all the KLA combat developments in this neighborhood of Prizren was that of May 26, 1999, when KLA units killed two Serbian special police officers during an action.

In the report of the Regional Center of the KMDLNJ in Prizren, dated 23. 02. 2009: “Consequences of the war in the Municipality of Prizren”, it is written: “On 26. 05. 1999 at 07:30, KLA units attacked the Serbian police in the ‘Tusus’ neighborhood by surprise, precisely at the time when the shift was being made, since for some time the movements of the Serbian forces in this neighborhood had been observed.

On that occasion, two policemen were killed. The murder of the policemen took place on Str. “Ramiz Sadiku” (now Xhevat Berisha) of this neighborhood. The killed policemen had bags with them with them with items looted from the abandoned houses of Albanian citizens.” In the first half of June 1999, Human Rights Watch interviewed three refugees in Albania who were eyewitnesses to what happened in Tusus on May 26, 1999.

Meanwhile, on June 14, shortly after NATO entered Kosovo, a Human Rights Watch researcher visited the Tusus neighborhood of Prizren. He photographed the destruction caused by Serbian forces and interviewed fourteen residents of Tusus. The violence in Tusus would flare up after the killing of at least two Serbian police officers on Ramiz Sadiku Street, the main boulevard that runs through the entire area.

A number of witnesses told Human Rights Watch that they had heard about the killings, while another witness, L.V., stated that he had seen the bodies on the morning of May 26. “One (of the police officers) was lying on his back,” explained L.V. “While the other one had fallen face down, his back riddled with bullets; his back was soaked with blood.” The Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs has published the names and photographs of the two police officers killed in Tusus on May 26: Milosav Rajkovic (born in in 1975), and Zlatomir Stankovic (born in 1957).

Numerous Serbian military, police and militia forces, unable to destroy the bases of the KLA units, in the early hours of the morning of May 26, 1999, launched a comprehensive offensive of a vengeful nature on the innocent civilian population. “At 9:30 the offensive of the Serbian forces began.” – writes the RC of the KMDLNJ in Prizren.

Serbian criminal units brutally entered house after house, and in this frantic operation, looted, burned and gutted 245 houses in this neighborhood. In this situation, Serbian criminal units separated men from women and children and mercilessly executed 25 men of different ages. This genocidal operation continued until the afternoon.

Many witnesses who survived the massacre say that special police forces were involved in this bloody operation, in coordination with mixed Serbian military and paramilitary formations, who were wearing camouflage uniforms (green), some of them wearing masks on their faces, while others had scarves tied around their heads. An 11-year-old boy told Human Rights Watch researchers that they were carrying “big daggers” and “smoking cigars.”

Another witness spoke of the presence of “Greeks and Russians who did not speak a word of Serbian.” Witness F. K., 33, a resident of Tusus, told Human Rights Watch researchers that he and 16 members of his family – on the morning of May 26 – “had taken a seat in the cellar of the house and heard multiple shots.” The gunfire, he said, “was relentless, very close, maybe fifty meters from my house.

After half an hour of continuous shooting, they started burning and demolishing the houses in our neighborhood. They destroyed everything.” He stated that the fire continued until dawn, when he and his family would escape by climbing over the yard wall and walking between the burning beams to reach the road that would take them out of the neighborhood.

Members of other families would describe how Serb forces had entered their homes, sometimes to kill, sometimes to search. Witness L. V. (a 16-year-old boy) told Human Rights Watch researchers: “More than fifteen Serbs came to the house. They asked us, ‘Is there a KLA here?’ They searched the whole house and stayed inside for about five minutes.

They were special police forces and they were wearing the red Serbian flag on their arms. They took me out of the house and said, “We will kill you. Look at the people of the house for the last time, we will kill you.” When L. V. was taken out of the house, a man, who according to him was the commander of the Serbs, told the others to let her go. L. V.’s mother was also mistreated; she said that at that moment she thought that the security forces were going to take her away, but only the screams of her mother-in-law saved her. Their house would be visited more than once by groups of Serbian security forces, because it is located right in the middle of “Ramiz Sadiku” street.

Where “Ramiz Sadiku” street ends is the house of the Abdylmexhidi family, whose six male members were brutally murdered and massacred by Serbian criminal forces on May 26, 1999. Witness Jehona (Sami) Abdylmexhiti-Thaci, (born 04. 12. 1980) describes that terrible day as follows:

“On 26. 05. 1999, it was a Wednesday, I was in my house in Prizren, 6 Rugova Street, ‘Tusus’ Neighborhood, with my family, my uncles and some cousins, there were 15 of us in total. Early in the morning, around 8.30, the Serbian police and military forces started burning the houses in this neighborhood. Around 11.00, the flames approached our house. We were in panic and did not know where to go, what to do.

At one point, 6 of our men headed towards the main road (former Dedinja Street). However, they were stopped by the Serbian police and military and sent back home. They backed them up against the wall of our house, searched them and demanded money. They took my father – Sami – inside the house and in the presence of my mother, Fejzije, they demanded money.

On this occasion, they threatened my mother: “if you don’t give me money, we will kill your husband”. Out of fear, my mother gave them 2000 DEM. They hit my uncle Rafet with the barrel of an automatic rifle and demanded money from him as well. I know that he also gave you Serbian dinars, but the police and soldiers threw them away and took the marks.

This whole difficult and terrifying situation was witnessed by my uncle’s 4 children, three women, my grandfather – Vaiti and my grandmother – Zymyle. All the time they were telling us where the KLA is, where is America, we will kill you all, and other provocations. After taking the money from the mother, they took the father outside and backed him against the wall, along with his uncle – Rafet, his two brothers (Shefik and Behar), his cousin (Hyrmet), his uncle’s son (Mirsad), while from Mirsad’s house, which is next to ours, they brought my aunt’s husband (Hesat) and my aunt’s son (Bejan), who they also pinned against the wall, a total of 8 people.

In the meantime, they searched the house, but they didn’t find any weapons. Then they told us women and children to go outside. We headed towards the main road. After 3-4 minutes, we heard gunshots – in bursts. We didn’t dare to turn back. There were a lot of forces on the road. In the afternoon, my grandmother Zymyle (my father’s mother) entered the house while the house was burning, and saw traces of blood and documents and other personal belongings scattered on the ground, but she didn’t find any bodies.

We were hopeful that maybe they were alive. After two days, Bejan’s father (Xhevat) went to the police and asked for his son, but they told him: “go to God, ask for him, … leave quickly because we will kill you too.” On Friday, May 28, 1999, Xhevat Xhemshiti went to the morgue and identified: Bejan and Hesat, while on the same day my mother, Fejzia and aunt Servete identified: my father – Sami, my uncle – Rafet, my brothers: Shefik and Behar, my cousin – Hyrmet and my uncle’s son – Mirsad in the hospital morgue. They were buried on the same day in the Prizren cemetery.” – concludes the testimony of Jehona (Sami) Abdylmexhiti-Thaci.

The “Human Rights Watch” researcher interviewed two witnesses who had taken the bodies of the killed – from the Prizren hospital morgue, in the following days. Witness M. B. (65 years old) said that, “he and a few of his friends had taken from the morgue that Friday a couple of dozen bodies, including a thirty-four-year-old woman who had been completely burned; she had lived on the same street as him.”

He remembers when: “The morgue doctor” – he told him – “that we had to decide: either we take them and bury them, or they would put them all in a common grave. I carried some of the bodies in a cart.” Another 65-year-old witness, F.D., told Human Rights Watch researchers that he went to the morgue for several days in a row, taking two or three bodies each time. He also attended the funeral of some of the dead, one Sunday, in the cemetery near the local mosque.

Residents of the neighborhood who had experienced this terrible massacre remember that Serbian forces left Tusus in the afternoon (on May 26), before nightfall. And as the Serb troops were leaving, a truck arrived in Tusus to collect the bodies of the executed men, which they took to the morgue of the Prizren hospital. Witnesses told Human Rights Watch researchers that the group of people in the truck consisted of an Albanian driver, four Serbian civil servants, and four Roma, who had been hired as porters to load the bodies.

“The truck was full of bodies,” said one witness. “It was open at the back, so they were easy to see. The Roma went from house to house looking for the bodies. They picked them up and threw them into the truck as if they were sacks.” Another witness said she had seen a large number of bodies wrapped in white sheets in the back of the truck, one of the civil servants holding a camera and filming the dead.”

From the testimonies collected in this neighborhood, it is learned that on May 26, 25 unarmed Albanian civilians were cruelly executed in the houses and streets of Tusus:

- Rafet Abdylmexhiti 1947,

- Sami Abdylmexhiti 1951,

- Shefik Abdylmexhiti 1978,

- Behar Abdylmexhiti 1982,

- Mirsat Osmani 1975,

- Hyrmet Sylejmani 1964,

- Hesat Xhemshiti 1937,

- Bejan Xhemshiti 1975,

- Bislim Qengaj 1921,

- Selvinaze Qengaj 1923,

- Salih Elshani 1936,

- Ymer Thaqi 1945,

- Avdi Berisha 1921,

- Refki Berisha 1961,

- Hajrim Arifi 1977,

- Sani Bajrami 1968,

- Neki Gashi 1935,

- Selim Berisha 1932,

- Feim Berisha 1927,

- Xhemajli Poniku 1933,

- Halil Poniku 1937,

- Fazile Maqkaj 1968,

- Rexhep Maqkaj 1923,

- Nijazi Muja 1959, and

- Fadil Ramadani.

Serbian war criminals

Serbian war criminals

How Enes and Fatmir Muharremi were executed in the “Bilbidere” neighborhood of Prizren

In another neighborhood of Prizren, in the “Bilbidere neighborhood,” 10 days earlier, before the Tusus massacre, on May 16, 1999, Serbian paramilitary forces killed Enes and Fatmir Muharremi in their home. Human Rights Watch interviewed family members about the execution of Enes and Fatmir. Witnesses said that by the end of April, almost all the residents of the neighborhood had fled to Albania, while their family and six other families remained there.

Three weeks passed without incident, until one Sunday, May 16, a group of Serbian police officers arrived to search the house for weapons. Not long after the police officers had left, a large group of paramilitaries arrived. E. Muharremi, a 26-year-old woman, reported Huma n Rights Watch about what happened: Arkan’s men, about a hundred of them, arrived at around 9 a.m.

He remembers well that “they wore sky-blue scarves and special vests that kept them unbuttoned; so you could see their chests. They wore necklaces with crosses and other emblems around their necks. Most of them had shaved heads; some had beards. Among them was a bearded Russian; he didn’t speak a word of Serbian… They had painted their faces and the area under their eyes.

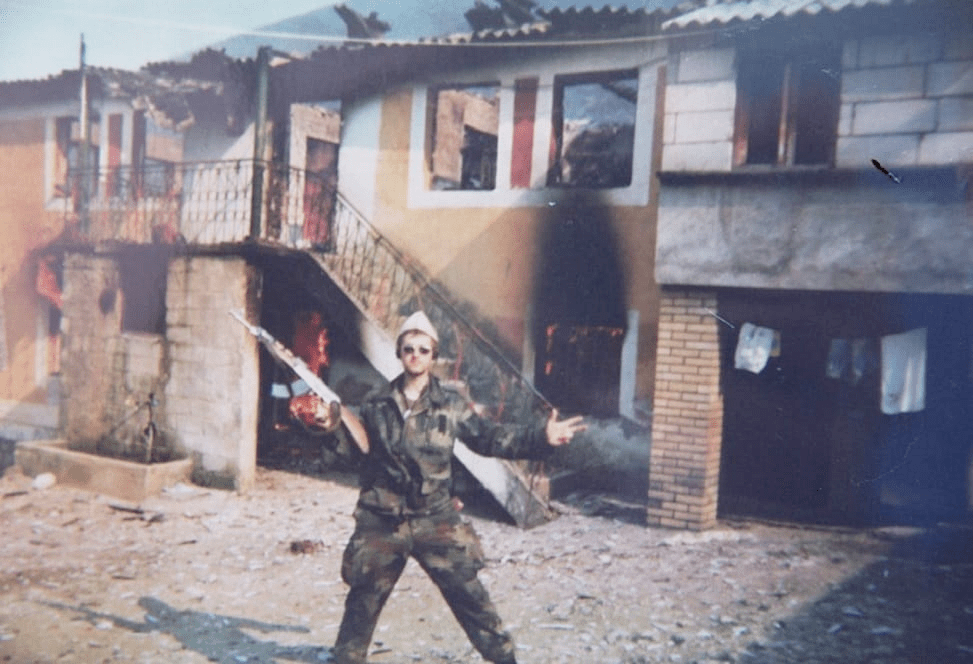

Albanian homes burned by Serbs.

They were wearing green camouflage uniforms, like army uniforms, while a small group wore dark blue… They didn’t come to our house, but were scattered all over the neighborhood. Fear had entered our hearts.” E. Muharremi remembers that the paramilitaries took her two brothers-in-law, Elez and Enes Muharremi, as well as Enes’ son, Fatmir Muharremi. It wasn’t long after they took them that the family members who remained in the house heard the bursts of automatic weapons.

A. Muharremi, the mother of the two brothers, continued to explain: “I heard the gunshots. ‘I’m afraid they killed them,’ I said to the other boy … it was a whole burst of fire from an automatic rifle.” After the paramilitaries left the neighborhood, the family members found the bodies of the two men in the bathroom of a nearby house.

Enes’ surviving brother told Human Rights Watch: “I heard the screams of the women who had found the bodies, so I ran towards them. A neighbor told me, “Don’t go inside, you won’t be able to bear that sight,” so I didn’t go in. I set off for the police station to report it, but on the way I met three of them.

They came with me to the house where the bodies were and we went into the bathroom together. There we saw the bodies, sprawled on the floor. Blood was everywhere. Enes had been shot twice, in the chest and arm; Fatmir had been shot in the chest and leg. The police did not take the bodies to the morgue.

Memorial in the neighborhood

After the war, Enes and Fatmir, along with the 25 martyrs of Tusus, rest peacefully in the common cemetery, at the end of the neighborhood of the Braves (formerly Tusus).

“Our bequest: Work, love and help each other, appreciate this freedom that our blood and thousands of others brought you, if you do not want history to repeat itself… …Kosovo washed with blood for centuries, may our blood be lawful, farewell to historical Prizren, may our blood become light…”

– this is what is written on the inscription of the monument erected in the Tusus neighborhood (now the neighborhood of the brave) in Prizren, where the names of 27 Albanians killed and brutally massacred on May 16 and 26, 1999, by Serbian criminal forces are engraved.

Why is no one pursuing the criminals?

After the end of the war, when the displaced population returned to Kosovo, they found military documents and even photographs (many photographs of Serbian criminals were also found in the Tusus neighborhood of Prizren and the surrounding area), in which Serbian military and paramilitary forces are clearly seen in action, smiling mysteriously with weapons in hand in front of houses that had been engulfed in fire, they are seen looting the property of Albanians.

Although the names of the criminals who committed thousands of massacres have been identified by people who survived the crime, to this day none of those responsible for security in Kosovo, neither the police or the EULEX prosecution, nor the Kosovo police or the local prosecution, nor other international institutions, nor local ones (Government, Presidency, Parliament or civil society), have shown even the slightest interest in pursuing and arresting these criminals.

Meanwhile, EULEX is pursuing and arresting freedom fighters, who with weapons in hand protected the population from extermination! When all these facts and thousands of others like them are taken into account, the entire political and institutional leadership of Kosovo naturally becomes responsible for not filing a criminal lawsuit against the Serbian state, for the genocide and ethnocide committed in Kosovo.

On May 26, 1999, Serbian criminal units, after looting, burned and gutted 245 houses in the Tusus Neighborhood! (See some photos taken by activist Bajrame Tafallari)

References

https://pashtriku.org/masakra-e-tususit-ne-prizren-me-26-05-1999-gjenocid-i-pandeshkuar/

Under the Power of Orders (Municipality of Prizren) – War Crimes in Kosovo – October 2002 by Human Rights Watch (pages 359 – 367)

Municipality of Prizren – http://kk./rks-gov.net//prizren/City-guide/Geography,aspx, and wikipedia.

Serbian Crimes in Kosovo 1998 – 1999, Book 2 – Prishtina 2010,

Report of the Regional Center of the Human Rights Commission in Prizren, dated 23. 02. 2009 “Consequences of the War in the Municipality of Prizren”. Human Rights Commission – War Crimes in Kosovo 1998 – 1999 Monograph 1, Prishtina 2010.