Written by Dr. Qazim Namani, Prishtina, July 2024. Translated by Petrit Latifi.

Battle of Prapashtice 1944. The fighting during 1944 for the protection of the border in the village of Prapashticë

After the capitulation of Italy and the formation of the Second League of Prizren on September 16-19, 1943, in order to protect the liberated Albanian areas, the need to create an army was felt to protect the ethnic lands and the Albanian population.

In these circumstances, the Albanians thought that in order to protect the Albanian population in the northern areas, they should form several divisions with Albanian volunteers, who would be supported and armed by the German army. The formation of these divisions would also suit the German army, which was now significantly weakened, and aimed at its withdrawal from the areas of Greece, through the territory of Kosovo.

The Chairman of the Central Committee of the Second League of Prizren, Bedri Pejani, at the end of March 1944, sent a letter to Hitler, requesting the arming of the Albanians of Kosovo, and requesting Germany’s help in liberating all Albanian territories occupied by the Slavs. Bedri Pejani requested the formation of an “SS-Skënderbeg” division with Albanian volunteers.[1]

(On the cover: Photo taken in 1944, in Prishtina, showing young Albanians, barefoot and ragged, alongside some young soldiers.)

With the formation of the Llapi sub-prefecture, and the establishment of power by the Albanians, the organization of Albanians around the Balli Kombëtar as a political party was also carried out, which was against the communist spirit with a right-wing Western orientation. The political program of this organization was supported by all Albanians in this area. The population of Llapi was mobilized to defend the ethnic border from the source of the Llap-guri river in Uglarit-Përpellac to Prapashtica.[2]

The forces of the Second League of Prizren, although they did not have much time to consolidate militarily, were responsible for defending the border in the northeast from the Sandzak to the Karadak mountains. The main forces of the Albanian army, those of the IV Pristina Regiment, commanded by Colonel Fuat Dibra (Fuad Xhaferraj), were concentrated on the part of the border from Mitrovica to Gjilan, which would encounter Yugoslav partisan brigades from the end of the summer of 1944, and during the autumn and winter of that year.[3]

This letter was sent to Himmler by the head of the German state office for review. With the help of Germany in April 1944, the Second League of Prizren formed a Division with Albanians, but a number of those mobilized initially deserted.

Considering the general circumstances created, after April, the desertions of Albanians from the “SS Skanderbeg” division, must be viewed from the circumstances of the situation created on the ground and the attacks of Slavic armies towards Albanian lands.

The Albanians of Kosovo, after the occupation by Serbia in 1912, had not enjoyed any elementary national rights, until 1941. Serbia had not given them any rights, they had no schools in the Albanian language, they were not employed, the best lands had been taken by the state, to give to Serbian settlers, the Albanians lived under the violence of the gendarmerie and great pressure to move to Turkey. From 1941 to 1944, the Albanians established their own state institutions and for the first time developed an education system in the national language, returning part of the territory within the borders of an Albanian state.

On the other hand, the Orthodox of Kosovo during this period organized themselves and cooperated with the Chetniks in Serbia. Chetnik corporations were formed within the territory of present-day Kosovo. The Second Kosovo Chetnik Corps, by the beginning of 1944, had mobilized a number of volunteers somewhere between 1500-1700, and was among the largest Chetnik Corps in Serbia.[4] This Corps, in 1944, openly collaborated with the German army, and in some actions actively participated in the fighting alongside the German army.

On the other hand, the Provincial Committee of the LNÇ for Kosovo, in February 1942, had issued a proclamation emphasizing that after the victory against fascism, the peoples themselves would decide their own fate. Shala’s party organization managed to expand its influence in the territory of Llapi, in Obranxhe, Sekiraqë, Shajkoc, Orllan, Braine and Nishec up to Jabllanicë. [5]

In July 1942, Mustaf Hoxha from Nishec had entrusted you with the task of connecting the partisan units of Kosovo with those in Jabllanicë to fight Bajraktar, and the meeting took place in the village of Tullar. During this period, Mustaf Hoxha’s house in the village of Nishec was the base for the connection between Kosovo and Jabllanicë.[6]

During 1943, at the proposal of the Provincial Committee from Jabllanica, to the Shala-Podujevo-Braina-Jabllanica connection, Ali Shukriu was transferred.[7] In addition to the organization of other checkpoints, a checkpoint of the National Liberation Council was formed in the village of Dabishec.

illegal partisan, who took on the task of maintaining contact with the movement in Preševo and Gjilan.

In December 1943, Ali Shukriu, Rasim Qerkezi and Qazim Bajgora met in the village of Brainë, where they discussed the purpose of the LNÇ, and at the Second Meeting of AVNOJ, they also discussed the formation of the Shala Partisan Regiment. At the beginning of August 1944, a group of about 30 people from Drenica had arrived in Shala, who crossed into the territory of Jabllanicë, and on August 26, 1944, near Medvedja they formed the Shala Partisan Regiment, Riza Voca was appointed commander.[8]

The association of some Albanian partisans from Kosovo, to cooperate with the Serbian partisan regiments operating in Jabllanicë, had not gained the trust for a joint war.

The Chetnik formations that were established within the territory of Kosovo, collaborated closely with the intelligence services of the German army, until the end of the war, when they joined with the Serbian partisan units and committed major crimes against the Albanian population.

In a telegram of the German intelligence service, dated April 13, 1944, it is stated that Žika Markovići, commander of the Second Kosovo Army Corps, is ready to place himself under German command with 4,000 soldiers.[9]

In order to realize this strategic platform, the Germans sought cooperation with the nationalist forces of the Montenegrins, Serbs and Bulgarians, promising them rewards with other Albanian lands. This policy of the Germans contradicted the platform and positions of the Second National League of Prizren, and the non-communist Albanian parties that demanded the formation of ethnic Albania.[10]

At this time, the Albanian Communist Party, supervised by emissaries of the Yugoslav Communist Party, accepted the pro-Slavic communist government in Old Albania, without the new Albania, and after four years of freedom, accepted to satisfy Slavic interests by reoccupying Albanian lands.[11] Seeing the reports of the fighting, the defeat suffered by the Germans, and the support given by the Anglo-Americans to the Slavic-Russian army, the Albanian Communist Party made this decision in the hope that Tito and his partisans would adhere to the agreements and cooperation for a joint war against the German army.

In these lonely and allyless circumstances, the nationalist leaders Xhafer Deva, Rexhep Mitrovica, Qazim Bllaca, Xhelal Mitrovica, and other leaders of the Second League of Prizren, began a new organization for the defense of the ethnic Albanian borders. The Nationalist Youth League for the Defense of Kosovo mobilized able-bodied men for war.

‘The youngest battalions were formed: the “Nazim Gafurri” battalion with commander S. Vala Sicanin, the “Hasan Prishtina” battalion with commander Ibush Ibrahim, the “Zija Gashi” battalion, the Llapi battalion, the Drenica battalion and the Sandzak battalion. Shashivar Aliu from Banja e Mitrovica was appointed commander-in-chief of these battalions.[12]

Around 20,000 men responded to the general mobilization, who were deployed along the border from Ceraj to near Kumanovo. The fourth Prishtina regiment, under the command of Colonel F. Dibra, put up strong resistance until the command in Tirana gave it a firm order to withdraw. The Hasan Prishtina battalion continued to maintain its positions in the vicinity of Podujeva, until almost all of its personnel remained on the battlefields.[13]

The Albanian guerrilla forces fought against the Bulgarian and Yugoslav armies, hoping that the Albanian National Liberation Army that had penetrated Kosovo would join them in the fight against the occupying army.[14]

The Albanians of Kosovo, who in 1941 had been divided into three zones, found it difficult to form a compact organization into an organized army to withstand the attacks in 1944 by numerous enemies. Nevertheless, a rapid mobilization and organization for the defense of the country at the end of 1943 and until November 1944 is to be praised and honored because this was the only way to protect Albanian interests and territories.

The government of Rexhep Mitrovica, which was founded at the end of 1943, faced many internal problems, so in these chaotic situations for the Albanian country and territories, it took the appropriate steps to protect the Albanian lands, supporting the desire and will of the traditional Albanian patriotic forces for a common state and the liberation of the occupied lands.

After the divisions between the Albanian political blocs, at the end of 1943, and until the end of 1944, there was a period of political and military confrontation, ending with a fratricidal war at the end of World War II.

The internal crisis in the Albanian government made it difficult to work for unity, a stable political order to calm the country and to create a new composition of the political and intellectual elite.

The heightened tensions and divisions of the communist bloc with the government of this period also made it difficult for the divisions of the Albanian political wings of the other three thought that for a short time this elite would be dismissed.

In the national patriotic and state-forming aspect, there is no doubt that the Government of Rexhep Mitrovica was the last elite group that made an effort to implement a state-forming policy, for the protection of the borders of Albanian lands and national unity.

During the government of the government of Rexhep Mitrovica, the issue of Kosovo and other Albanian regions was revived, for a more just and realistic solution, within the framework of an Albanian state. It is understood that Rexhep Mitrovica and his government sacrificed for this ideal, indirectly cooperating with the Germans, who conceived them as invaders, but at the same time as the only possibility, for the realization of aspirations for national unity. This government represented those political forces in the entire Albanian territories that had the most advanced programs, for the solution of the national issue.[15]

Under these conditions and circumstances, it was impossible to resist the attacks of the Slavic army, which was organized to re-conquer Kosovo.

With the beginning of the Slavic attacks on Albanian lands in early 1944, the Albanian population and youth of this time were uneducated, poor and uninformed about the developments of the time. Most of these young Albanians and families lived in remote rural areas and had previously mainly been engaged in livestock and agriculture.

Few had visited more than one nearby town. It was a youth who had no knowledge of the roads of Kosovo, let alone the developments of military operations and military alliances of the time. These young people who had grown up in families with their family memory, of the violence and massacres that the Serbs and Bulgarians had committed after the occupation of their lands. To protect their families, they needed weapons, clothing, and to stay close to their families, so even if they were equipped with weapons, they deserted.

The situation and poverty of the Albanian population in April 1944 is best shown by this photograph taken at that time in the center of Pristina.

Albanian forces mobilized mainly from Albanian residents of the border belt, on March 19, 1944, had dealt a severe blow to the partisan units of Jabllanicë, who passed through the Albanian villages of Pristina, to create a corridor connecting them with the Serbian Chetnik units mobilized in the Kosovo Plain.[16]

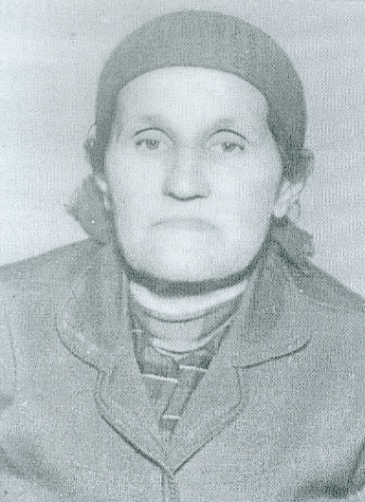

During the passage of the partisan group to a place called Bunari i Thatë, this group was discovered by Bejto Jusuf’s daughter, who raised the alarm with a rifle shot. An armed clash took place there, in which two partisans, Bata Ibrović and Radoja, were killed. This girl who started the fighting was rewarded by the then government in Pristina.[17]

At the age of 21, Xhemilja married in Grabofc. For the events of March 1944, she was arrested in Grabofc and sent on foot to the Pristina prison. Her father Isufi had also been arrested in the Pristina prison. In the trials, Xhemilja was sentenced to two years and six months, and she spent two years in prison. After spending nine months in the Pristina prison, Xhemilja was transferred to the Niš prison. Even after serving her sentence, Xhemilja was constantly followed by agents of the Yugoslav state.[18]

Xhemile Isufi – Topi-Zogiani

The situation was very difficult in Llap and Galab, especially in the villages on the ethnic Serbian-Albanian border. Among the most important strategic points were the villages of Barainë, Nishec and Prapashticë, which were separated by the border line with the villages of Tullarë and Gubafcë.[19]

Starting in May 1944, the northern part of Kosovo was attacked by Tito’s partisan detachments, coordinated simultaneously with Mihajlovic’s Chetnik units.[20]

The mobilized Chetnik units continued to undertake armed attacks in the direction of Kosovo, and other Albanian territories. On May 23, 1944, two villages of Suhadoll in the vicinity of Mitrovica were attacked, and attacks on Albanian families in Peshter continued. Several detachments of Chetnik units attacked the villages of Galab: Brainë, Prapashticë, Hajkobilë, Dabishec, Nishecë, Brvenik, Metërgoc and Turuçicë.[21]

In May and June 1944, organized attacks by the Serbian-Macedonian army began on the border line from Kitka to Përëpollac in Podujevo. The Slavic army encountered strong resistance from the Albanian army. The fighting between the Albanian army and the Slavic formations continued in the following months.

Until May 1944, one soldier per household was mobilized in the Albanian regular army to defend the border. It is important to note that from the summer of 1944 until Pristina was occupied, every male who was capable of holding a weapon from all Albanian families was mobilized to defend the border. While women and young girls were also trained to use weapons. While from October, every resident who was capable of using weapons was mobilized on the front line, and every household to support and help the fighters.

Bulgaria, as an ally of Germany, since 1941, had created its zone of interest by including within the Bulgarian state, the region of eastern Kosovo. This situation lasted until September 1944, when Bulgaria, under pressure from the Russian army, capitulated, and opposed the German army.

With the capitulation of Bulgaria, a large military alliance was created between the Russian army, the Bulgarian army, and the Yugoslav army, against the German army which had begun to withdraw from the territory of Greece towards the north. This large Slavic military alliance had planned to penetrate the Kosovo plain, to confront the German army.

To enter Pristina and the Kosovo plain, of course the shortest route from Jablanica was through Prapashtica. To prevent the penetration of the Slavic army into the border strip with Serbia, the 4th Regiment of the Albanian Army and units of the Second League of Prizren were mobilized. Of course, with the beginning of the war, volunteers from nearby villages and other Albanian regions also acted in the border strip, joining the Albanian army.

During this period, the National Liberation Army of the former Yugoslavia of Tito had joined forces with units of the Chetnik aradhes and Macedonian brigades, which planned attacks from the border points in Llap and Galab.[22] As can be seen, with the unification of all Slavic formations against the Albanian army, the re-occupation of Kosovo was planned, as well as ethnic cleansing by killing and displacing as many Albanians as possible.

In the summer of 1944, on the Albanian side, partisan detachment cells were also formed that operated illegally in several villages: Brainë, Prapashticë, Dabishec, Nishec and Koliq.[23] The Brainë partisans were tasked with operating in the Brainë-Prishtinë relationship, and from the Kosovo Plain to transfer the advanced element, and organize this in the Partisan Front.[24]

During September 1944, the XIII Army Corps was formed, with four divisions of the Serbian army and the second Bulgarian army, where they clashed with the German military forces of Army Group “E”, which intended to withdraw through the Kosovo Plain.[25]

In early September, Albanian forces of the 4th Pristina Regiment had a fierce battle on the outskirts of Podujevo with Yugoslav partisans and several Bulgarian units, who were trying to penetrate Podujevo. On this occasion, three Bulgarian motorized divisions were destroyed, which were already retreating from the communists.

The youth battalion from Vushtrri “Hasan Pristina” also participated in these battles, which suffered heavy losses.[26] These were attacks by the Slavic army on the border line from Bervenik to the village of Hajkobilla, but mainly the fiercest fighting took place in Prapashtica.

Bulgaria declared war on Germany on 6 September 1944. The German army took swift measures to expel Bulgarian forces from Kosovo and present-day Macedonia. The Bulgarian Fifth Army retreated to the old borders of Bulgaria.[27]

The Bulgarian First and Second Armies, on 8 October, attacked the German forces again, occupied the towns in the Morava plain and entered Kosovo. After heavy fighting, the Bulgarian First Army entered Pristina. After the penetration of the Bulgarian army and several units of the Soviet army into the central part of Kosovo, the German army’s communication links along the Ibar River valley were severed.[28]

In September, when the attacks by the Slavic army increased, four battalions of the Albanian army came to the aid of the Albanian army on the border.[29]

In early October 1944, the Bulgarian Second Army and the UNÇJ brigades, also assisted by the Soviet Army of the Ukrainian Front, aimed to occupy Pristina through the territory of Prapashtica.

The Albanian army, now reinforced, put up strong resistance in the battle of October 18, 1944, against two regiments of the Bulgarian army. After a three-day battle, the Bulgarian army was defeated by the Albanian army and the volunteers mobilized to protect the border. Regarding this battle, the newspaper Lidhja e Prizrenit wrote that on October 18, in this battle, the Bulgarian army left 600 soldiers on the battlefield, while about 60 other mobilized soldiers and volunteers were killed on the Albanian side.[30] In this battle, the Albanian army managed to capture some cannons and animals for carrying ammunition.

The patriotic forces of the Albanian volunteers and the Albanian army, led by the Albanian League of Prizren, during this period for three consecutive months, had waged fierce fighting on the Skopje-Kumanovo-Kitka-Merdare border line and especially in the village of Prapashticë. Fierce fighting took place from 15 to 22 October, when the Serbo-Bulgarian army forces reached the Orllan-Brainë-Lisicë (Prapashticë) [31] and Hajkobilë (Q.N) line.

Seeing the danger of the occupation of Kosovo by the armies of In August 1944, the Committee of the Second League of Prizren formed the “Youth Committee for the Defense of Kosovo” in Pristina, and ordered the formation of district committees in the Kosovo plain and the border areas with Serbia. These committees were formed during the time when German forces were withdrawing from Greece, and when military forces were stationed around the Kosovo border. Mobilization was carried out under the slogan “Defense of Kosovo from the Partisans”. These military units waged a bloody war against the LNC army, the Bulgarian aradhes, and ensured the withdrawal of the German army from Kushumli to Pristina.[32]

The Second League of Prizren formed the National Youth Committee for the Defense of Kosovo, along ethnic borders. All men from the age of 18 to the age of 50 were mobilized to defend the borders. On October 18, 1944, the general youth command called for general mobilization. On 30 October, a proclamation was issued for all Albanians to mobilize militarily and economically to defend the border.

Units of the Youth Committee for the Defense of Kosovo from the Mitrovica District were placed under the command of Bahri Gjinaj and Major Aziz Shashivari.[33] In October 1944, soldiers from the Mitrovica region were deployed to the Mitrovica-Prepellac-Merdare-Brainë-Prapashticë-Hajkobillë border positions.

The 4th Regiment of the Albanian Army, four battalions of the “Albanian Nationalist Youth” and volunteer forces of Albanian residents in the border area and from the central part of Kosovo and Shala se Bajgora. It is believed that close to 7,000 combat troops from the Albanian side were concentrated in the border belt alongside a much larger number of Slavic forces.

Fierce fighting took place along the border line from Kepi i Reçicës, Prepellac, Podujevo to Konqul. In particular, enemy forces attempted to penetrate Pristina by attacking the border points in Prapashtice, Prepellac, Podujeve, Orllan, Dabishec, Hajkobilë (Gjelbrishte), Zajqec, Sfircër, Zhuje, Kitke and other border points up to Konçuli.

The first attacks began on October 15, in Lisinë of the village of Prapashtice, and other places, but the enemy army was severely defeated by Albanian forces led by Albanian officers Captain Pjetri, Demiri from Korca, Shyqeria, Isak Domi, Mulla Idrizi, Shefqet Bullykbashi, Mulla Sefë Govori, Captain Marku, Nazmi Budrika, Hajdari and Bajram Krasniqi, and several other leaders from the population of the villages of Gollaku who knew the terrain well and showed great heroism during the fighting.

In addition to the losses in men, the Bulgarian army also lost a large amount of weapons: 12 cannons, a machine gun, a mortar, hundreds of rifles and about 60 draft animals.[34]

The attacks continued on October 25, October 31 and only on November 19, when the Serbian and Bulgarian armies managed to break the border line. After this battle, the Serbian and Bulgarian armies penetrated Pristina, killing unprotected civilians of the Albanian population. Major battles between the Albanian volunteers and the Serbian army took place in the mountains of Keqekolla.

In order to withdraw with the least possible consequences, the Germans supplied all the armed groups that were against the army of the Russian army bloc of the peoples of the region who had mobilized against the German army with weapons.

On 10 September 1944, the Germans gave Žika Marinković, commander of the Chetnik Corps of Raška, three wagons of ammunition and rifles.[35]

During September and October, the Germans also provided weapons for the first time to Albanians who had mobilized to thwart the Bulgarian army, which, together with the Russian and Yugoslav armies, intended to concentrate in central Kosovo.[36]

From mid-October 1944, the German army began to withdraw from Thessaloniki and other Greek cities. This army numbered about 350,000 soldiers. The headquarters of Army Group “E” under the command of Colonel General von Lehr withdrew northward through the territory of Kosovo. General von Lehr, in order to withdraw with the least possible loss to the German army, took security measures, since at that time the Bulgarian motorized units that had the Russian army in the rear were forced to begin movements towards Kosovo and other Albanian areas to attack the German army on the Kosovo plain.[37]

In these circumstances, von Lehr formed two groups of soldiers in combat readiness. The “Langer” group was authorized to occupy Kusumli, to close the enemy forces’ route from Podujevo, and the other group, “Bredov”, was to close the Bujanovac-Gljan-Pristina road. More than 6,000 Albanian soldiers were mobilized on the border line, especially on the Bujanoc-Kitka-Sfirc-Prapashtic-Merdar-Prepellac-Kepi i Uglarit border line in Reçic, in order to facilitate the journey and rescue of the “E” army, so that it could pass freely from Ferizaj towards Mitrovica.[38]

In October, the Russian platoon of the Second Battalion with 158 fighters was offered as reinforcement to the command of the Third Ukrainian Front and the Red Army.[39]

To strike the Germans, the Russian army had ordered the Bulgarian army to block the roads for the withdrawal of the German army into the territory of present-day Kosovo. The Albanian army, which was also commanded by some soldiers from Albania, had been mobilized to defend the Albanian border. The entire Albanian population of Kosovo, capable of shooting with weapons, had been mobilized on the border. Now the Albanian national army had been mobilized on the border.

For the first time, the Albanians in this battle were supplied with weapons and assisted by German military personnel to defend the border. The Bulgarian army, which had the Russian army in the rear, aimed to attack the border line in Prapashtica, to penetrate as quickly as possible to Pristina, to concentrate on the Kosovo Plain. In addition to Prapashtica, the mobilization of Albanians had also taken place at other strategic points along the north-eastern border of Kosovo. Since mid-October 1944, the Bulgarian army and Serbian army units began attacking the Albanian army.

Fierce fighting took place especially in Prapashtica. On October 18, the two Bulgarian army units turned back after leaving many dead in Prapashtica, by the Albanian national defense forces. The Bulgarians suffered heavy losses in Prapashtica, also on October 23 and 25 when they attempted to enter Kosovo. The Bulgarian army, after heavy losses, had lost its morale for the war.

On October 29, 1944, the Bulgarian army again suffered heavy losses in men and military arsenal in Prapashtica. In November, the Serbian and Bulgarian armies penetrated into Prapashtica and Keqekollë, where they burned and looted both villages. On 19 November, the Bulgarian and Serbian armies entered Pristina, and retaliated against the Albanian population, shooting nearly 55 of the most prominent figures in the city of Pristina.

After several days of fighting, on 19 November 1944, units of the Bulgarian 2nd Army, with the 14th Brigade of the 46th Division, the 13th Serbian Corporation and the 5th Kosovo Brigade, reoccupied Pristina.[40]

After the Slavic armies entered Kosovo, in the Llapi district, local Serbian elements, with the help of partisans from the 27th Brigade of the 46th Division, began to attack the Albanians in that area. The Slavic army, in early December 1945, undertook operations to purge the “Counter-Revolutionary” forces. The 25th, 26th and 27th Brigades of the 46th Division, as well as units of the 22nd Division, participated in this action.[41]

By order of the Supreme Commander of the UNC of the former Yugoslavia, J. B. Tito, the power of the Military Administration was established in Kosovo. All army troops located in Kosovo, with about 30,000 forces, were placed under the command of the military administrative power, and new military units began to be brought in from other parts of Yugoslavia, at a time when the Kosovo partisan formations were sent northward outside the territory of present-day Kosovo.[42]

Another bloody frontal battle to capture Pristina began with large reinforcements from the Russian army in late October and early November 1944. This Slavic army with reinforcements and heavy weapons attacked Prapashtica on October 31, but encountered strong resistance from the Albanian and volunteer army, where fierce fighting took place along the entire Prapashtica-Pristina road. Very fierce fighting took place in the Keqekolla mountains.

The resistance of the Albanian army lasted until November 19, 1944, when the Yugoslav and Bulgarian armies managed to capture Pristina. The Serbian-Bulgarian army, during its penetration into Pristina, had killed Albanian civilians, burned many households and raped women who were caught on the streets fleeing before this army.

The League’s defense forces, together with other volunteer forces, despite heavy fighting and losses during September, stopped the penetration of Yugoslav partisan units that were aiming to enter Kosovo from the north, east and south.[43] The Yugoslav partisan military forces, which were assisted by Soviet partisans, were superior in numbers and armament, so the Albanian forces were inevitably defeated.[44]

In these circumstances, the Albanian nationalist patriotic forces, in the war against the Slavic communists, were fueled by a sincere nationalism of popular origin, which was related to the defense of the threshold of the home and the homeland.[45] In these circumstances, the Albanian army and the Albanian population of the border belt had no other alternative than general mobilization against the Slavic army, and the defense of the Albanian inhabitants in those villages. Of course, they were unsupported, without heavy weapons and in much smaller numbers than the Slavic armies.

Starting from September to November, due to the blows that the Germans received in the east from the Red Army, and other forces of the Balkan peoples, supported by the British, The Germans and the Americans thought about how to withdraw with minimal loss in men, equipment and military logistics.[46]

In these circumstances, the Central Committee of the Second League of Prizren was forced to withdraw, and after this the oppression and persecution of the Albanians began. The V Division, later the VI Partisan Division from Albania, gathered around 10,000 Albanian partisans and 40,000 Yugoslav partisans, organized the major operation supposedly to pursue the German army, where around 2,000 Albanians were executed in Tivar, and the penetration of thousands of other Albanians through Prizren, Lumë, Pukë, Shkodër, Hani i Hotit, Tivar and up to Dubrovnik, sent by Yugoslav partisan forces, and observed by Albanian pursuing forces, and thousands more who were sent towards Belgrade and Novi Sad, where most of them did not return alive to their families.

During this clash during October and November 1944, the civilian population of the village of Prapashticë and other villages of the border strip had taken refuge in Albanian villages inside Kosovo.

These bloody battles have left many memories and stories of Albanian families of the border region. Without a doubt, the contribution of each family to these battles was great, so I am offering some of the stories preserved by my grandmother and grandfather, leaving a message for other residents of the border region to describe the memories of their grandparents. By describing the stories of family members, I think we will make our contribution to fill the lack of sources, and many events that residents did not have the courage to tell because they were followed by informants and partisans loyal to the Yugoslav government.

After the end of World War II, Tito’s policy was to register one fighter in each family, in order to give them pensions, and to offer them as collaborators of the government. In the early 1950s, the ruling communist party appointed trusted people to reward the partisans with pensions and other privileges. Those who were left out of these privileges were persecuted, imprisoned and forcibly deported to Turkey and other countries.

Below I am giving some of the family memories carefully collected by my grandfather and members of the Shushnic family from the village of Prapashticë.

During the summer of 1944, for the protection of the border, the headquarters of the Albanian army under the leadership of Captain Pjetri, Shyqerija, Demir Korça and Isak Domi, the headquarters stayed in the room of Shaban Musa of Shushnic, until the Albanian army command ordered that connections for cooperation with the partisans and the APJ should be made.

After this decision was made at the beginning of November, the headquarters was set up about 5 km to the other end of the village, to connect with the members of the Shala detachment, who were operating in the village of Nishec. The connection with the Yugoslav communists was not well received by the Albanian military. My grandfather recounted, we all knew that the partisans were not to be trusted, we all even called them Russophiles. After the connection with the Yugoslav communists, Tefik Çanga came to Prapashtica, whom my grandfather had never met, but had heard from other villagers about his capture in Prapashtica.

Ali Berisha writes that Tefik Çanga had come to Prapashtica on a mission to form a unit of 40 people who would operate on the border that separated Prapashtica from Jablanica, to tell the Slavic partisans that it is enough that we control this area, you have no reason to operate beyond the border when we are there.[47]

Tefik was noticed by Hysen Sergeant, Haki Gremja and Ramadan Varoshi, all three from the Ferizaj district, mobilized as volunteers, went to Keqekollë and reported him to the commander of the gendarmerie, Rexhep Akllapi. Rexhep informed the prefecture in Prishtina about Tefik’s stay in Prapashtica. In these circumstances, Tefik Çanga was kidnapped in Prapashtica and hanged in the city of Peja.[48]

Regarding the kidnapping of Tefik Çanga, in the nineties of the 20th century, I conducted an interview with Rexhep Gajtani from the village of Prapashtica. Rexhep said that after the kidnapping, Tefik had asked for a cup (a tin cup to drink water from). Rexhep had offered him water and remembered that, while Tefik was drinking the water, he said: Indeed, I am an Albanian communist, but all my life I have worked and acted for the national unification of Albanians.[49]

On October 18, the two units of the Bulgarian army turned back after leaving many killed in Prapashtica by the Albanian national defense forces. The Bulgarians suffered heavy losses on October 23 and 25 when they attempted to enter Kosovo through Prapashtica. The Bulgarian army had now lost its morale for the war after heavy losses. On October 29, 1944, the Bulgarian army again suffered heavy losses in men and military arsenal at Prapashtica.

In this battle, my late grandfather told how he managed to capture a Bulgarian army horse, which was loaded with ammunition.

ion. According to the stories, my grandfather was in this battle with an Albanian from Shala, who had taken up position at the wall of Nedelku’s house (a settler who had previously been located in the center of the village of Prapashticë). There, around us, fierce fighting was taking place between the Bulgarian army and the Albanian army. Our rifles had heated up so much that they were not even firing properly.

For a moment, we noticed that a loaded horse was coming near us. With great speed and care, I managed to grab that horse by the bridle and put it into Nedelku’s house, my grandfather said. The horse had been loaded with weapons and ammunition. We secured the other weapons to continue the fight, and for a short while, the two of us were left alone. After a short time, they heard our villagers calling, so we went out and joined them.

When we got to Xhehem (a locality in the village), we entered the house of Bul Brahim. He remembered that there had been three killed Albanian soldiers there, who had been carried after being killed at the front. My grandfather had taken that horse and brought it home. After a few years, my grandfather had put this horse in the field to thresh grain, and when he had approached this horse to change the direction of its walk on the field, the horse had suddenly torn off half of his ear. My grandfather was angry with this horse, and after hearing that the Italians were buying the horses in Leskocë, this one with another Albanian, had sent the horses for two days’ journey, and had sold them in Leskoc.[50]

After the war, the Albanian population of the village had suffered greatly. The new government with the partisans had taken away their food and animals. With tears in his eyes he would tell them that even their magic had been wiped out and they had been left without flour.[51] All the villagers had sent their animals to Keqekollë except for Shaban of Musa of Shushnicë, and they had sent the police to demand the surrender of the animals. [52]

In these times of crisis, my grandfather had gone to the Kosovo plain to find some grain. We did not bring the animals home but kept them hidden on the Straka mountain (Mountain in the village). Differences appeared between the inhabitants and the families, some families were privileged, while the majority of Albanian families were persecuted by the authorities.

They only gave help to trustworthy people. We were completely burned and destroyed, it was cold and I went to Keqekollë, after I heard that they were giving away a meter of nylon to close the windows. They did not even give me the nylon, they said I did not deserve it, my grandfather often said.

According to my grandmother’s accounts, during the Bulgarian-Serbian army offensive, the children and women had fled from Prapashtica and taken refuge with her father Ajet Krasniqi, in the Viti i Mareci neighborhood. They had stayed there for several weeks until Pristina was occupied. The Slavic armies had killed any Albanian residents they had caught on the way to Pristina. Several villagers who had volunteered to see if their houses had been burned were killed by the Bulgarian army.

She told of two Albanian sisters who, with a son of about 7 years old, had been arrested by the Bulgarian army after they had approached the village of Prapashtica. Both of these women were taken to the mountains of Keqekolla and were systematically raped by Bulgarian soldiers, until one of them died from the violence. After her death, the other sister and her son were released and told of the horror they had experienced.

Another detail worth mentioning about the behavior of the Bulgarian soldiers was the case when, after returning to their homes, the families found everything destroyed. The houses were burned and dilapidated, the food was looted, while in the crates (cheese tins) with livestock products the Bulgarians had performed their physiological needs, polluting all the collected dairy products.[53]

The newly formed partisan government imprisoned, killed and displaced innocent Albanians from their ethnic lands. Despite the actions of the army and the arrests, a number of escaped Albanians continued their resistance against the partisan government. At this time, the NDSH district committees began to be organized. This resistance continued until 1947.[54]

In addition to the youth committees established in the districts, the NDSH youth committee was also established in the Prishtina Gymnasium. Among the 11 students in this organization was Rrahman Latifi, born in Prapashtica, and as a sympathizer of this organization was Shaban Sheqiri, a student from Podujevo.[55]

Some of the members of the Albanian National Democratic Movement, who had remained in Kosovo, found shelter in other Albanian families. Most of them were investigated and killed by the Yugoslav OZN. Some others were betrayed by the Albanians themselves, being killed for disloyalty. After the defeat of the NDSH organization, until 1948 Azem Bellaqevci and Musli Dumoshi remained on the run, but on February 21, 1948, both were killed in the guest house of Musliu’s friend in the village of Prapashtica.[56]

For the Serbo-Bulgarian army, it was not important whether the Albanians had formed a partisan actions, in agreement with the Yugoslav partisans. As a concrete case, we also have the village of Nishec, the birthplace of Mustafa Hoxha, commander of the Meto Bajraktari battalion, who had long collaborated with Tito’s partisan ranks. Although the center of action of the Albanian partisans was established in the village of Nishec, when the Yugoslav People’s Army and the Bulgarian army entered, they used violence against the Albanian inhabitants, killing 14 Albanian residents, arresting about 100 women, children and the elderly, and burning the house of Hamit Dede, the guard of the partisan battalion.[57] As can be seen from these actions of the Serbo-Bulgarian army, the main goal of this army was to kill and expel Albanians from their homes.

The Bulgarian army had beaten some men from the village of Nishec and forced them to open their graves, and had shot and buried some of them in a single grave, tied together.[58] Mustaf Hoxha, as commander of the “Meto Bajraktari” battalion, had family ties with all those killed, but he had not been able to save even his own villagers. After the occupation of Pristina and the persecution of Albanians, Mustaf Hoxha did his best to save Albanians, but he also showed disappointment in his collaboration with the Yugoslav partisans.

Since the summer of 1944, and after the reoccupation of Kosovo by Tito’s partisan army forces, the Albanian population experienced persecution, mass murder, Albanian youth were mobilized and sent to be killed in Srem and Tivarë, the population was plundered, resettlement programs were implemented in Turkey, and the destruction of the material and spiritual culture of Albanians in the former Yugoslavia began. For the resettlement and killing of Kosovo Albanians, the UNÇJ had sent four divisions with 14 brigades to Kosovo[59], which began with massacres in Drenica and Gjilan.

After the Slavic army entered Pristina and the execution of citizens in Tauk-Bahqe, large massacres were also carried out in Prapashtica, Mitrovica, Rahavec, Vushtrri, etc.[60]

In such circumstances, when the Albanian population was in danger of being expelled from their ethnic lands, it was necessary to reorganize the Albanians around the Albanian National Democratic Organization. This organization had established committees in all areas of Kosovo inhabited by Albanians. Committees were also established for the territory of Pristina and Podujeva. The assembly held on August 17, 1945, in the village of Koliq, was attended by 26 members. Mulla Ramë Govori was elected chairman of the Podujeva district. This organization began by holding assemblies throughout the territory of Kosovo.

Murders, imprisonments, persecutions began against the members of this movement, and hatred and division spread among the people among the members of the partisan ranks. The secret services of the OZN liquidated many Albanian leaders such as Ajet Gërguri, Gjon Sereqi, Shemsi Gashi, Shyt Mareci, Mulla Idriz Gjilani, Azem Bellaqevci, Musli Dumoshi, etc.

Abazi i Islamit from the Balajve neighborhood of Prapashtica, had been displaced earlier and lived in the village of Keqekollë. After the occupation of Kosovo, many Albanian volunteers, who had been against the Serb-Slav army, set off towards the Greek border to save their lives. Among them was Abazi i Islamit from Keqekollë, who had been wounded twice in an attempt to cross the Greek border. After returning to his village, he stayed in the mountains, but was interrogated by the Serbian gendarmerie and seriously injured.

He lies wounded in the stream and for three days in a row no one notices him. Little Hyseni, 6 years old, and his daughter Shaha, after releasing their cattle, offer themselves to the wounded Islamit. Islami invites the children to help him, to tell Isa to get some lukewarm water and come as soon as possible. Isa, together with his stepmother Fate, go and help by cleaning his wound. Islami demands that without being investigated by the Chetniks, they meet him as soon as possible with Braha Shushnica of Prapashtica.[61]

Islami is sent to Braha’s village of Prapashtica through a slightly snowy alley at night. Braha, after giving them food, tells them not to worry, I will arrange a place where you will stay, recover and join your friends. Braha arranges a shelter in the mountains, where he would send him food every day and treat his wound.[62]

After three months of staying with Braha in Prapashtica, Islami recovers and secretly returns to his home. After a few days, the gendarmes realize that he has recovered and is now at home. Through Albanian gendarmes they try to talk to him to surrender with the promise that they will forgive him. After he surrenders, they send him to the prison in Niš, where they kill and bury him, so even today his grave is unknown.

The Shushnic family[63], a branch of the Shushnic family in the village of Prapashticë, had a good family organization during the war, and a solid economy for the time. Seeing the danger, on the eve of World War II, on their mountain “Straka”, near their family mill, they had built a shelter. Throughout all the times of crisis and danger in that Persecuted people, Kocac, but also some Jews who entered Kosovo from the territory of Serbia, spent the night in the shelter.

Musa of Shushnicëve had an early friendship with the Jewish family Bahar, in Prishtina. After Musa’s death, this friendship was continued by his son Shabani. Shabani was the head of this family until 1946. Brahimi (Braha), Musa had an uncle, and after the murder of his father Naman in 1921, he was raised in the care of Musa and Shabani. From this family, Braha was mainly responsible for taking care of the sheltered people, the mill and delivering food to the people sheltered in their bunker.

In this bunker, immediately after the battle of Gjilan, Arif Kllokoqi had brought Mullah Idriz Gjilani. Mullah Idrizi had stayed in this bunker for three weeks. From Prapashtica, Mullah Idrizi settled in Tyxhec, and then in Gjyrishec. Braha used to say that when it got dark, Mulla Idriz Gjilani would be brought to their room, and before dusk they would return him to the shelter. I have heard these stories several times from my grandfather Brahim Namani (Braha), but after his death, I visited the place where the shelter was with Shaban’s son Ferati. Ramadan N. Ibrahimi published a photograph of Ferati showing the family’s shelter.[64]

Ali Sh. Berisha also wrote about the Shushnic family’s shelter on the “Straka” mountain, and about the stay of Mulla Idriz Gjilani after the battle of Gjilani, as well as the shelter and recovery of Abaz Islam from Keqekolla.[65] In the village of Prapashticë, and precisely in the room of Shaban Musa of Shushnic, there was a point of contact between the Albanian army from Mitrovica and the Albanian army from Gjilani, so the members of this family had previously been acquainted with the commanders of both areas. As per family memories from the Gjilan area, in our family who had come to consult with the command of the Mitrovica area, Shqfqet Bylykbashi, Bajram Krasniqi from Tygjeci, Mulla Sefë Govori from Gjilan, Nazmi Budrika etc. were mentioned.

In conclusion to the tragedy of the Albanian people at the end of World War II, I am giving some conclusions of Izber Hoti.

Izber Hoti, regarding the fate of the Albanians and the cooperation with the PKJ, writes: The Albanian communists, after believing in the promises of the PKJ and the AKP, also joined the LNC, where together with the Serbian and Montenegrin people and others in Kosovo they formed detachments, companies and brigades of the UNCJ. On the eve of 1945, as is known, 8 brigades of the UNC and AP of Kosovo and Metohija were formed in Kosovo, a Brigade of the People’s Defense Corps of Yugoslavia, which together with the military units of the rear had nearly 50,000 fighters.[66]

As can be seen, the Albanian people also contributed to the war against fascism, these are facts that cannot be ignored and the assumption that Kosovo was “liberated” in 1944 is stable and cannot be denied, however. This is only one side of the coin, the other side of this coin is completely opposite to the first.[67]

Izber Hoti, in his study, writes that the re-national enslavement of Albanians in Kosovo and other ethnic areas by the Yugoslav communists was carried out deliberately from the beginning of World War II, and took on large proportions from the end of March 1944 to July 1945. The AKP blindly believed the promises of the PKJ, while the struggle of the Kosovo Albanians for national liberation was unsuccessful. As a result, Kosovo and other Albanian areas in Yugoslavia were re-occupied and re-enslaved.

The failure of the liberation of Kosovo, as well as the national unification of the Albanians, does not deny the LNC of the Albanians in Kosovo, nor the importance and contribution of this movement in the fight against fascism. However, by re-occupying Kosovo, the Yugoslav communists violated the promises and the principle of self-determination of peoples, to which they swore during World War II.[68]

I would add to what Izber Hoti wrote, the consequences of the divisions of the Albanians at critical and important moments to decide the fate of the people. I think that by analyzing some of the national tragedies in wars but also at the negotiating tables of the international level, the lack of unity of the Albanians, as a result of ideological, religious concepts and ambitions for power and enrichment, has cost the Albanians to remain fragmented into territories, divided and weak in the military, economic and intellectual aspects to protect vital national interests. We hope that in the future we will become aware to understand that national and state interests must be a priority before egos and individual and family ambitions for wealth and power.

Sources and Literature

1 . Tahir Zajmi, The Second League of Prizren, Brussels, 1965

2 Adem Ajvazi: Podujeva, The Foundation of the City 1912-1945, I, Podujevë 2020

3 Jusuf Buxhavi: Kosovo 1912-1945, Prishtina 2015

4 Mitrovica and the Region, Mitrovica, 1979

5 The Partisan Line of Kopaonik, Shala, and Ibar, Belgrade 1981

6 Hakif Bajrami, Partisan Battalion Meto Bajraktari, Prishtina 1988

7 Branko Lotos: Kosovska Mitrovica and the Surroundings in the Plans of Draze Mihajlovica, Radnicka Klasa 479 Secret and Public Cooperation of the Chetniks and the Occupiers, Archivski pregled, 1976. D.59: Mitrovica and the Surroundings, Mitrovica, 1979

8 Gjet Ndoj: The Government of Albania during World War II (1939 1944), Tirana 2023

9 Fazli Hajrizi: Rexhep Mitrovica in the National Movement, School Book, Prishtina, 2008

10 Ali Sh. Berisha: Gallapi i Prishtina IV, (1941-1945), Prishtina 2010

11 Muhamet Shatri: Kosovo in the Second World War, Prishtina

12 Izber Hoti: At the Crossroads of Albanian History and Historiography, Prishtina, 2003

13 Romeo Gurakuqi: Albania and the Free Lands 1939-1946, Second Edition Prishtina, 2023

14 Ramadan N. Ibrahimi: National Defense in the Prishtina Region, Prishtina, 2008

15 Stefan Karastojanov: Kosovo a Geopolitical Analysis, Skopje 2007

16 Qerim Lita: Reports for Albanian National Democratic Committees, Prishtina 2009

17 Qazim Namani: Massacres and Crimes of Serbs, Montenegrins and Others in Albanian Lands 1912-1944, Part I, Prepared for Publication by Nue Oroshi, Lumëbardhi Publishers, Prizren, 2023

18 Hysen Azemi, LNDSH and Serbian State Security, Volume II 1945-1947. Prishtina 2014

19 Mehmet Gërguri: Ajet Gërguri and the NDSH Movement (945-1947), Prishtina, 2007

20 Nuha Zullufi: A bright reflection of national history in Keqekollë, Prishtina 2018, p. 14

21 Ali Sha Berisha: Gallapi I Prishtina V (1950-1998), Prishtina, 2014, p. 108

[1] Tahir Zajmi, The Second League of Prizren, Brussels, 1965, p. 34-35

[2] Adem Ajvazi: Podujeva, The Foundation of the City 1912-1945 I, Podujevë, 2020, p. 366

[3] Jusuf Buxhavi: Kosovo 1912-1945, Prishtina, 2015, p. 343

[4] Mitrovica and the Region, Mitrovica, 1979, p. 392

[5] Partisan Line of Kopaonik, Shala, Ibar, Belgrade 1981, p. 312

[6] Ibid., p. 313

[7] Hakif Bajrami, Partisan Battalion Meto Bajraktari, Prishtina 1988 p. 113

[8] Mitrovica and the Surroundings, Mitrovica, 1979, p. 412

[9] Branko Lotos: Kosovska Mitrovica and the Surroundings in the Plans of Draze Mihajlovica, Radnicka Klasa 479 Tajna i

Javna saradnja četnika i okupatora, arhivski pregled, 1976. D.59: Mitrovica and the Surroundings, Mitrovica, 1979, p. 396

[10] Gjet Ndoj: Geverisja e Shqipërisje e Shqipërije veličar Župa II Mirja (1939 1944), Tirana 2023, p. 511

[11] Ibid., p. 511

[12] Ibid., p. 512

[13] Ibid., p. 512

[14] Ibid., p. 513

[15] Fazli Hajrizi: Rexhep Mitrovica in the National Movement, Liberi scholjan, Prishtina, 2008, p. 199

[16] Hakif Bajrami: Partisan Battalion “Meto Bajraktari”, Prishtina 1988 p. 108

[17] Hakif Bajrami, Partisan Battalion Meto Bajraktari, Prishtina 1988 p. 108, 109

[18] Ali Sh. Berisha: Gallapi i Prishtina IV, (1941-1945), Prishtina 2010, p. 388-391

[19] Muhamet Shatri: Kosovo in the Second World War, Prishtina, p. 48

[20] Romeo Gurakuqi: Albania and the Free Lands 1939-1946, Second Edition Prishtina, 2023

[21] Muhamet Shatri: Kosovo in the Second World War, Prishtina, p. 61

[22] Ramadan N. Ibrahimi: National Defense in the Prishtina Region, Prishtina, 2008, p. 58

[23] Hakif Bajrami, Partisan Battalion Meto Bajraktari, Prishtina 1988 p. 107

[24] Ibid., p. 107

[25] Muhamet Shatri: Kosovo in the Second World War, Prishtina, p. 178

[26] Jusuf Buxhovi: Kosovo 1912-1945, Prishtina 2015, p. 344

[27] Stefan Karastojanov: Kosovo a geopolitical analysis, Skopje 2007, p, 156

[28] Ibid., p. 156

[29] Ramadan N. Ibrahimi: National Defense in the Pristina Region, Pristina, 2008, p. 62

[30] Ibid., p. 64

[31] Muhamet Shatri: Kosovo in the Second World War, Pristina, p. 178

[32] Qerim Lita: References for Albanian National Democratic Committees, Pristina 2009, p. 13

[33] Gjet Ndoj: The Government of Albania during World War II (1939-1944), Tirana 2023, p. 512

[34] Ramadan N. Ibrahimi: National Defense in the Surroundings of Pristina 1941-1948, Pristina, 2008, p. 65

[35] Partisan Marches of Kopaonik, Shala, and Ibar, Belgrade 1981, p. 525

[36] Shaban Mahmut Rama from Tuxheci, from Gjilan, a fighter in defense of the border, and a participant in the infamous journey from Tivar to Dubrovnik. I conducted the interview in 1994, in Pristina.

[37] Mitrovica and the surrounding area, Mitrovica 1979, p. 417

[38] Mitrovica and the surrounding area, Mitrovica 1979, p. 418

[39] Partisan Line of Kopaonik, Shala, Ibar, Belgrade, 1981, p. 592

[40] Muhamet Shatri: Kosovo in the Second World War, Prishtina, p. 179

[41] Lefter Nasi: Reconquest of Kosovo, September 1944 to July 1945, Tirana 1994, p. 143

[42] Lefter Nasi: Reconquest of Kosovo, September 1944 to July 1945, Tirana 1994, p. 162

[43] Jusuf Buxhovi: Kosovo 1912-1945, “Jalifat Publishing”-Houston, “Faik Konica”- Prishtina, 2015, p. 344

[44] Ibid., p. 344

[45] Ibid., p. 344

[46] Gjet Ndoj: The Government of Albania during World War II (1939-1944), Tirana 2023, p. 510

[47] Ali Berisha: The Gallapi of Prishtinë

inës IV, Prishtina, 2010, p. 108

[48] Ibid., p. 110

[49] Interview conducted with Rexhep Gajtani, at his home in Prishtina, in 1994

[50] Qazim Namani: Massacres and Crimes of Serbs, Montenegrins and Others in Albanian Lands 1912-1944, Part I, Prepared for publication by Nue Oroshi, Lumëbardhi Publishers, Prizren, 2023, p. 98-99

[51] Ali Sh. Berisha: Gallapi i Prishtina IV, 1941-1945, Prishtina, 2010, p. 480

[52] Ibid., p. 479

[53] Qazim Namani: Massacres and Crimes of Serbs, Montenegrins and Others in Albanian Lands 1912-1944, Part I, Prepared for Publication by Nue Oroshi, Lumëbardhi Publishers, Prizren, 2003, p. 99

[54] Hysen Azemi, LNDSH and Serbian State Security, Volume II 1945-1947. Prishtina 2014, p. 5

[55] Qerim Lita: Reports on Albanian National Democratic Committees, Prishtina 2009, p. 73

[56] Mehmet Gërguri: Ajet Gërguri and the NDSH Movement (945-1947), Prishtina, 2007, p. 266

[57] Ramadan N. Ibrahimi: National Defense in the Prishtina Region, Prishtina, 2008, p. 73

[58] Ibid., p. 76

[59] Ibid., p. 85

[60] Lefter Nasi: Reconquest of Kosovo, September 1944 to July 1945, Tirana 1994, p. 150

[61] Nuha Zullufi: Bright Reflection of National History in Keqekollë, Prishtina 2018, p. 14

[62] Ibid., p. 16

[63] The “Shushënic” family is a branch of the Bala family of the village of Prapashticë, which has borne this name since the end of the 19th century, when a member of this family returned to his native village with a foreign hat that he had brought from the war. After carrying that hat from his other brothers, his family retained the epithet Shushnicë. Unlike the inhabitants of the village and surrounding villages, they are also known by other names such as: Drernoc and Bilallaj.

[64] Ramadan N. Ibrahimi: National Defense in the Prishtina Area 1941-1948, published in Prishtina in 2008, p. 125.

[65] Ali Sha Berisha: Gallapi I Prishtina V (1950-1998), Prishtina, 2014, p. 108

[66] Izber Hoti: At the Crossroads of Albanian History and Historiography, Prishtina, 2003, p. 291

[67] Ibid., p. 291

[68] Ibid., p. 294