Authored by Zafer Golen. Translated and edited by Petrit Latifi.

The artcle mentions Ottoman-Montenegrin border politics as well as bandit attacks in the years 1858-1860, and Montenegrin imperialism on Albanian inhabited regions of Nikşiç, Derbenak, Gaçka, İşbuzi, Podgorica, Trebinje, Kolašin, Taşlıca and Gusinje.

For any state to be recognized and accepted as legitimate in the international arena, it must first have certain borders. A piece of land with defined borders expresses national, political, military, cultural or religious meanings[ 1 ]. The recognition of the geographical borders of a state by other countries means that they respect the political will there.

Therefore, the most important issue that states have been sensitive about throughout history has been the determination of the borders that are the symbol of their sovereignty and the protection of those borders. Especially with the establishment of national states in the 19th century, states have been more sensitive about determining and protecting their borders.

In parallel with this development, the Ottoman Empire also began to give more importance to controlling its borders than before. For example, on 5 Muharram 1257/27 February 1841, the “Men-i Mürûr Regulation” was issued and domestic travel was taken under control[ 2 ]. Since 1851, people without a “murur tezkire” and since 1854, people without a “passport” were prohibited from entering Montenegro’s neighboring country, Bosnia and Herzegovina[ 3 ].

The Ottoman Empire’s effective control of its borders coincided with Montenegro’s desire for independence. Montenegro had no political influence within the Ottoman Empire until the 1850s. Dealing with Montenegro was the duty of the Pashas of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Shkodra. However, this situation changed when Danilo Petrovic Nyegoş[ 4 ] became the vladika[ 5 ]. Because he strived with all his might to establish an independent state on the lands he lived.

A- CONDITIONS PREPARING THE BORDER REGULATION

1- Banditry Activities of Montenegrins

Attacks on Albanians of Nikşiç, Derbenak and Gaçka

From the moment they came under Ottoman rule, the Montenegrins have been attacking the surrounding regions non-stop. According to them, banditry was a sign of heroism and a struggle for freedom for the Montenegrins. In reality, banditry was their most important means of livelihood. For example, in 1856, the Montenegrins first attacked Nikşiç, mowed the grass of the Nikşiç people, killed three people who tried to stop them, and then attacked Derbenak and Gaçka.

1,000 Montenegrins participated in the attack on Gaçka, 1,000 sheep and 100 cattle of the local people were stolen, and two three-year-old children were killed. The Ottoman administration, fearing the intervention of Austria and Russia, tried to prevent the attacks through Austrian state officials in Kotor and Dalmatia instead of responding directly to the Montenegrin attacks. However, the Austrian officials often did not even respond to the demands of the Ottoman administrators in this direction[ 6 ].

Attacks on Isbuzi

The efforts of the Ottoman Empire could not prevent the conflict with Montenegro. Because the Montenegrins did not comply with any official or unofficial agreements. For example, in 1856, the people of the Isbuzi district took an oath with the Montenegrins “besa” [ 7 ] that they would not attack each other[ 8 ], but the Montenegrins disregarded their oaths and burned the house of the Isbuzi District Governor Suleyman and looted his village.

Continous attacks on Niksic (Nikshich)

Again, on March 2, 1856, they attacked Nikshich and killed eight people, six of whom were Muslims and two were non-Muslims[ 9 ]. The attacks continued to increase in the following days[ 10 ].

Especially during the Bosnian-Herzegovinian rebellion that started in 1857, the intensification of attacks disturbed even the Austrians who indirectly supported Montenegro, and they sent a protest telegram to the Austrian governor of Dalmatia, Danilo, accusing him of disturbing the peace and tranquility in Herzegovina[ 11 ].

2- Attitude of the Great Powers

The main aim of the great powers[ 12 ] was for Montenegro to gain independence. In this way, a problem that bothered them would be eliminated and a state under their control would be established in the region. The same situation was valid even for England, which seemed to be an ally of the Ottoman Empire. British public opinion was completely against the Ottoman Empire. Many newspapers and magazines published harsh articles criticizing their country’s Montenegro policy. However, despite the public reaction, British politicians who pursued a balance policy towards Russia continued to support the Ottoman Empire.

The Russians, on the other hand, exploited the Montenegrins’ desire for independence for 150 years and used them as they wished. Whenever an Ottoman-Russian war or disagreement broke out, the loyal allies, the Montenegrins, rebelled and prevented the soldiers of regions with military resources, such as Bosnia, from going to the battlefields, successfully fulfilling their duty of delaying the Ottoman forces in the region.

The Russians, who did not want to lose such a trump card, used the Montenegrins when necessary and when their job was done, they managed the situation with delaying tactics. Since the Russians financially financed all the vladikas in Montenegro, where taxes could not be collected, the vladikas could not make much noise about this situation[ 13 ].

As in every Vladika period, Danilo’s greatest supporters were again the Russians[ 14 ]. After he became Vladika, the Tsar accepted him as a prince. Of course, the incident was met with a reaction in Istanbul and the Sublime Porte declared that it would not accept this fait accompli. Ottoman officials, who described the developments as “ugly” , emphasized that Montenegro was Ottoman territory[ 15 ].

Another state that directly supported Montenegro was France, on the one hand it appeared to be an ally of the Ottoman Empire, on the other hand it gave all kinds of support to the nationalist movements in the Balkans. For this reason, the French took an active role in even the smallest disputes regarding Montenegro[ 16 ]. This situation began to show itself clearly, especially after the Paris Peace Treaty, and they almost assumed the patronage of Montenegro.

They even sent a foreign policy expert named Henri Delàrue to Montenegro. Delàrue served as Danilo’s private secretary until his death. Delàrue frequently went to Paris during Montenegro’s most difficult moments, acted in accordance with the directives he received, and implemented the strategies developed in Paris in Montenegro. During his time as secretary, he became the absolute decision-maker on all matters concerning Montenegro[ 17 ].

Danilo was invited to Paris in 1857 and the French Government hosted him as a prince. The French consul in Shkodra personally organized all kinds of events related to this trip[ 18 ]. However, he writes that he tried to persuade Danilo to go to Istanbul, but could not persuade him because the Russians threatened to cut off his salary. Thus, he played the role of a friend of the Ottoman Empire and put all the blame on the Russians, from whom everything was expected[ 19 ].

Immediately after Danilo returned to Montenegro on May 10, he went to visit him[ 20 ]. The French were the only country that provided direct arms aid to Montenegro in the process that started with the Herzegovina rebellion of 1857[ 21 ]. Murad Efendi, the head of the border determination commission and secretary of the Bosnian Inspection Officer Kemal Efendi[ 22 ], describes the political influence of France on Montenegro with the following sentences[ 23 ]:

“The traditional raids of Montenegrin bandits into Herzegovina after the Crimean War and during the reign of III. “Since Napoleon had entered into competition with Russia and taken over to some extent the protection of the Slavic peoples in the east, it had ceased to be a frequent occurrence and had expanded considerably. The character of these sheep-stealing raids changed; they had become political in their purpose, meeting the needs of war and revenge as well as national economic aims.”

The Austrians are the old friends and protectors of the Montenegrins. Whenever the Montenegrins were in trouble, the Austrians took it upon themselves to save them. The situation did not change in 1853, when Danilo first clashed with the Ottoman Empire.

The conflict began when the Montenegrins captured Jabyak (Zhablak) on the night of November 24, 1852[ 24 ], and the Austrian government gave an ultimatum to the Ottoman Empire, which brought the Ottoman military operations to a halt in February 1853. Not content with stopping the military operations, the Austrians, taking the Russians and the French with them, put pressure on the Ottoman Empire to accept Danilo’s principality and to cede Grahova to Montenegro[ 25 ].

B- BORDER DETECTION STUDIES

1- The Emergence of the Idea of Border Determination

The idea of determining the border between the Ottoman Empire and Montenegro was first brought to the agenda during the negotiations of the Paris Peace Conference in 1856. Danilo, who came to Paris for this purpose, applied to the representatives of the great powers attending the conference and requested the determination of the borders of his country. Danilo, who had remained neutral during the Crimean War, requested the recognition of Montenegro’s independence in return for this action[ 26 ].

The Montenegro issue came to the agenda during the discussion of the 14th protocol on 25 March and the 15th protocol on 26 March of the Paris negotiations. On 25 March, the Austrian Foreign Minister Count Boul asked the head of the Ottoman delegation, Mehmed Emin Âlî Pasha, about the Ottoman Empire’s thoughts on Montenegro. Âlî Pasha replied that “the Ottoman Empire sees Montenegro as an inseparable part of it and has already declared this situation, but as a sign of its good will, it does not intend to change the current situation” [ 27 ].

The representatives of the great powers also advised Danilo to discuss his demands with the Ottoman Empire and closed the issue[ 28 ]. The Ottoman Empire also acted more sensitively on this issue, and after the Paris negotiations, the expression “to these people and subjects who are subjects of the imperial sultanate” began to appear frequently in official records[ 29 ].

Despite all his efforts, Danilo could not get an article regarding Montenegro included in the treaty, so he left Paris and returned to Montenegro, and on May 31, he conveyed his reaction to the representatives of all the countries attending the conference with a protest. It is significant that Danilo signed his protest as the prince of Montenegro and Brda. On the same day, he published a manifesto addressing the great powers, summarizing his demands in four articles[ 30 ]:

1- Montenegro’s independence must be recognized by international diplomacy.

2- The borders should be expanded on the Herzegovina and Albania sides.

3- The border between Montenegro and Türkiye should be determined like the border between Montenegro and Austria.

4- Bar (Antivari) should be left to Montenegro, thus providing the country with access to the sea.

Attacks on the Albanian villages of Nikşiç, Gaçka, İşbuzi, Podgorica, Trebinje, Kolašin and Gusinje.

When Danilo returned from Paris, rumors spread that he had accepted Ottoman citizenship[ 31 ]. The truth was the opposite. Far from accepting Ottoman citizenship, he supported the rebels in Herzegovina with all his might and openly attacked Nikşiç, Gaçka, İşbuzi, Podgorica, Trebinje, Kolašin and Gusine.

Although Danilo could not get what he wanted in Paris, he managed to convince the great powers that a border determination was necessary. Meanwhile, the Paris Ambassador Mehmed Cemil wrote that the British, French and Austrian consuls conveyed to him as friendly advice that they wanted some arrangements to be made in favor of Montenegro[ 32 ].

In parallel with the developments in Paris, the Austrian and French consuls in Shkodra carried out some work to determine the lands suitable for agriculture along the Montenegrin borders. Following the developments, the Sublime Porte also sent an order to the Mutasarrıfs of Herzegovina and Shkodra, requesting that the possible areas to be left to Montenegro be determined in a possible border determination study[ 33 ].

2- Decision on Border Regulation

The involvement of European states in the events greatly disturbed Ottoman authorities. The Sublime Porte attributed the Montenegrin attacks to poverty and thought that the issue would be resolved if the Montenegrins were given a piece of land where they could farm and graze their animals. To this end, the Sublime Porte took action to resolve the issue and began unofficial negotiations with the British, French and Austrian consuls on the “Montenegro border arrangement” .

On February 2, 1857, the British ambassador to Istanbul, Stratford de Redclife Canning, sent a report to the Minister of Foreign Affairs Clarendon stating that he had reached an agreement with the French and Austrian representatives regarding Montenegro and that the Grand Vizier also supported the establishment of an arrangement on this issue.

The British diplomat stated in his report that Danilo could also accept an arrangement based on the preservation of the current status quo. He even believed that if Montenegro could be given access to the sea and Spezzia on the Dalmatian coast could be given as a port, Montenegro would gain real administrative independence and therefore accepting the Sultan’s sovereignty would not be a problem.

Although Redcliffe stated that this last proposal was subject to the permission of the British government, it is clear what the British understood by border arrangements[ 34 ]. However, the rebellion that broke out in Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1857 turned all plans upside down. Naturally, the Ottoman Empire spent all its energy on suppressing the rebellion and for this reason the border determination work was delayed for a year.

Taking advantage of the easing of the rebellion in Herzegovina due to the winter, the Sublime Porte sent a secret order to the governor of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the governor of Shkodra, requesting the determination of the miri lands in the border regions that could be left to the Montenegrins[ 35 ].

However, the Ottoman authorities were definitely not in favor of drawing a border line, except for minor adjustments. In fact, when the agreement reached with the consuls in 1857 was brought up again in the Special Assembly meeting held on 14 February 1858, the Ottoman Government made the following decisions[ 36 ]:

1- In return for the unconditional recognition of Ottoman sovereignty by the Montenegrins and the Montenegrin chief (vladika), the internal administration of ancient Montenegro would be left to them.

2- In return for the chief who assumes the administration of Montenegro using the title given by the Ottoman State and accepting that his chieftainship be confirmed by a decree, he will be given a rank and a suitable salary.

3- In return for the Montenegrins ending their banditry activities, they will be given the right to trade throughout the state and to travel everywhere with ease.

4- The people of Montenegro will be able to benefit from agriculturally suitable miri lands and pastures in the regions bordering Montenegro, and in return they will only pay tithe.

5- Mekteb-i Şahane will also be open to children from Montenegro. In return, the Montenegrin metropolitanate will be subject to the Greek Patriarchate.

6- The road between Herzegovina and Shkodra (Ishbuzi-Nikshich road[ 37 ]) will always be safe and open.

7- No taxes will be collected from Montenegro, if collected, it will be spent for Montenegro.

As can be understood from the above statements, what the Ottoman Empire meant by border regulation was the leaving of the miri lands on the Montenegrin border to the use of the Montenegrins.

In order to put the Tanzimnâme into effect, a border determination commission was established in February 1858 and the Bosnian Inspector Kemal Efendi was appointed as its chairman. An instruction was also prepared to be given to Kemal Efendi at the same Special Assembly. In addition to the above articles, the instructions also decided how the work would be done. ‘

Kemal Efendi would first go to Bosnia and meet with the governor of Bosnia and the governor of Herzegovina and be invited to Vladika Herzegovina by a method they would find appropriate. If he or one of his men came, the above requests and privileges would be conveyed to him or his representative.

If accepted, the Vladika would be offered the Ottoman civil service and a salary of 75,000 kuruş, and if the offer was accepted, some of the lands in the border regions of Montenegro would be given to their use. As Kemal Efendi was also strictly warned, there would be no cession of even the smallest piece of land to the Montenegrins. In fact, he did not have the right to speak about the lands to be opened to the use of the Montenegrins without asking Istanbul or receiving its approval.

Kemal Efendi would also be careful about the requests for information from foreign consuls. Since the current tâzimnâme was prepared together with the British, French and Austrian consuls, they would be informed. However, the Russian consul’s involvement in the tâzimnâme negotiations would be politely prevented and his requests for information would be rejected[ 38 ]. Kemal Efendi left Istanbul on 13 March 1858[ 39 ].

The re-emergence of the issue also spurred Danilo into action, and on 28 February 1858 he sent a letter to the British Foreign Secretary James Howard Harris (The Earl of Malmesbury), stating that it was difficult to distinguish the current Ottoman-Montenegro border and that the border between the two sides should be determined like the Austria-Montenegro border determined in 1842, and asking for his help on this issue. In his reply on 22 April 1858, Harris reminded him that Istanbul had resolutely started border determination work and advised him to stay away from provocative actions[ 40 ].

While the border determination discussions continued, the Ottoman Empire received unexpected support from Austria. In an article published in the Ost Deutsche Post newspaper on March 2, 1858, the expression “so-called state” was used for Montenegro, and it was clearly declared that Montenegro was a part of the Ottoman Empire and under the sovereignty of the Sultan. The same support was repeated on March 5[ 41 ].

3- The Grahova Issue and War

While planning the border arrangement, the most important issue was the status of the small town of Grahova on the Herzegovina border. The Ottomans considered Grahova a part of Herzegovina, while the Montenegrins considered it their ancient land. Hundreds of clashes took place between the two sides to seize Grahova. As a result of the bloody clashes, neither side was able to gain an upper hand over the other, and the struggle ended with a treaty on the status of Grahova on October 20, 1838.

According to the treaty signed between the Governor of Bosnia Mehmed Vecihi Pasha, the Governor of Herzegovina Ali Pasha and the Vladika of Montenegro Petar, Grahova was accepted as a neutral zone[ 42 ].

Two more agreements were made between Ali Pasha and Petar on the status of Grahova on 24 September 1842 and 9 November 1843. Both agreements were about determining the borders and preventing attacks[ 43 ]. Istanbul never recognized these agreements. The clan leaders living in Grahova continued to obey the vladika.

With the death of Ali Pasha and Petar in 1851, the local agreement agreed between the parties thus became null and void. During the Montenegrin military operation of 1852/53, Derviş Pasha entered Grahova and brought the clan leaders to heel, and Yako Dakoviç, who was appointed voivode in 1838, lost his life during the conflict. However, with the withdrawal of the Ottoman forces, the administrative vacuum in the region continued[ 44 ].

In the rebellion that started in Herzegovina in 1857, Grahova was again one of the most important shelters of the rebels. For this reason, the Ottoman army entered Grahova in the spring of 1858. However, the Russians and the French claimed that Grahova had a neutral status and strongly opposed the military operation.

The British put forward the idea of establishing a commission consisting of representatives of the great powers and the Ottoman Empire to determine the borders. In response, the Germans and the Austrians recommended that an agreement be reached with the rebels and that if Grahova was not evacuated by the rebels as a result of the negotiations, the military operation should continue[ 45 ].

The issue was discussed in detail at the Imperial Majlis, which convened in Tophane-i Amire on 27 Ramadan 1274/11 May 1858 to evaluate the situation. As a result of the discussions[ 46 ]:

1- Determination of the Montenegro border

2- Rejection of the proposal to establish an international commission

3- The detection work was carried out through Ottoman officials.

4- The Bosnian Governor Kani Pasha gave the Montenegrins eight days to evacuate Grahova.

5- In case of evacuation of Grahova, the military operation will be stopped.

6- With the evacuation of Grahova, a council consisting of notables was established there and the local administration was transferred to that council.

7- It was decided that if Grahova was entered, the troops would be withdrawn and positioned in a suitable place on the border of Grahova.

The members of the Ottoman cabinet were unaware that their army was about to be defeated in Grahova on the night they met. Therefore, they used a dominant language and talked about evacuating Grahova either by kindness or by force. However, the war rendered the above-mentioned decisions void and the defeat of the Ottoman army in Grahova turned all plans upside down[ 47 ].

On the day the Grahova War began, on May 11, a manifesto was published in the semi-official French newspaper Moniteur, stating that “Montenegro was independent and the Ottoman intervention was unjust .” Because the manifesto was based on the idea that the Montenegrins would be defeated. The French made a move to preserve Montenegro’s current status quo in case the Montenegrin forces were defeated[ 48 ].

However, the course of the war was not as expected, and the Montenegrins won a decisive victory in the war that took place on May 11-13[ 49 ]. In the face of this unexpected development, the French sent two warships , “Algesiras” and “Eylau” , under the command of Admiral M. Jurien de la Gravière, to the Adriatic on May 20 in order to prevent a possible Ottoman reaction.

The ships anchored in the port of Gravosa, one mile from Raguza. Following the French ships, two Austrian frigates named “Danube” and “Bellocca” also arrived in the port. On May 30, the French ships set off for Budva, the closest point to Montenegro[ 50 ]. Admiral Gravière went to visit Danilo accompanied by his country’s consul in Shkoder[ 51 ].

The activities of France attracted the attention of even the Americans, and an article in the New York Observer and Chronicle stated that “with the support of France, Montenegro’s independence is close” [ 52 ].

After Grahova, the local administrators, who were worried, sent one request for help to the center after another[ 53 ]. Thereupon, soldiers were sent to the region via Raguza to control the Montenegrin border. 8,000 Ottoman soldiers transported by seven steamships landed in Raguza on May 31, 1858.

The soldiers reached Trebinje in mid-June. This reaction frightened the representatives of the Great Powers and the Montenegrin Vladika, and they put pressure on the Ottoman Government to prevent a possible Montenegrin military operation. The Ottoman Government, which retreated under pressure, was forced to declare that it would be content with only taking the rebellious districts in Herzegovina under control and preventing Montenegrin attacks[ 54 ].

4- Border Determination Efforts After the Battle of Grahova

The Battle of Grahova did not prevent the border works of Montenegro, but changed the course of the works[ 55 ]. Ottoman authorities reminded the embassies that the great powers should not get involved in the Montenegro issue, by referring to the seventh article of the Paris Peace Treaty of 1856.

The Ottoman Government continued by saying that “the emergence of such a proposal cannot be seen with pleasure by the Great Powers, who are committed to preserving the independence and complete property of the Sultanate of the Exalted” and clearly stated that the pressures exerted on them regarding the determination of the borders were inappropriate.

Despite the objections of the Ottoman Government, the British insistence on the determination of the borders by a commission consisting of representatives of five states put the government in a difficult position. The British wanted Montenegro to have access to the sea and to give Spezzia on the Dalmatian coast as a port. The Ottoman administrators, on the other hand, thought that accepting the British demands would mean recognizing the independence of Montenegro. In the meantime, a neglect made in the past gained time for the Ottoman Empire.

As a result of the research, it was understood that the state did not have a map showing the ancient Montenegro lands. Ottoman officials claimed that the British offer would be invalid in this case and that the ancient Montenegro lands should be determined first. In the face of the developments, the French consul intervened and a middle ground formula was agreed upon.

According to this formula, which the Ottoman Government accepted as a “lesser” option , the ancient Montenegro lands would be determined by a commission of engineers consisting of representatives of five states, and the determined map would be discussed in Istanbul and the final result would be reached[ 56 ].

However, it is understood that the Ottoman Government was not satisfied with this solution and only said yes to the French offer to gain time. According to the Ottoman strategy, the rebellion in Bosnia and Herzegovina would be suppressed in a short time with the forces sent, and thus the government would be able to spend all its time on the Montenegro issue[ 57 ]. The government preferred,

1- To regulate the Montenegrin border through its own officials.

2- To eliminate the victimized image of Montenegrins in the eyes of Europeans by giving them a piece of land where they can cultivate while making border arrangements.

3- In case of an attack by Montenegro on the border regions after the borders were determined, the Europeans would legitimately intervene in Montenegro and take control of the region (vladika) by referring to the border arrangement.

The Ottoman authorities were sure that even if the border arrangement was put into effect, the Montenegrins would not keep their word. For example, the Bosnian inspector Esseyyid Ahmed Aziz clearly stated that such an arrangement would be of no use, saying , “Since the Montenegrins are not a nation that keeps their word and they will break the agreement for a trivial reason when it suits them and they will not be left behind in corruption, their word and deed cannot be trusted and trusted…” [ 58 ].

However, due to the determination of the great powers regarding the border determination and the failure to suppress the rebellion in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the Ottoman State could not implement its own plan and had to accept the border determination despite all its drawbacks[ 59 ].

5- Engineers Commission and Its Work

There was no full consensus among the five states on the border determination. The goal of the Russian and French bloc was to ensure Montenegro’s independence, or if this did not happen, to preserve the situation that existed in 1856. The Austrians were against the work. The Prussians, on the other hand, were thinking of remaining neutral. Neither country trusted the other.

For example, the British ambassador in Petersburg wrote in a telegram to London on June 17, 1858, that the Russians did not trust the British and French engineers who would participate in the border work and that they were suspicious of the decisions to be made. The Austrian Dalmatian Army Commander, General Mamula, was of the opinion that Danilo was a puppet in the hands of the French.

In other words, the Austrians either did not trust the French or thought that their influence on Danilo would be dangerous for them[ 60 ]. The conflict of interests between the countries was also reflected in the convening of the Engineers Commission. Because each country waited until the last moment to send its own engineer. For example, while the Russian engineer Captain Vlangaly was just leaving Odessa to go to Raguza on July 8, the British began to hint that they could withdraw from the commission, complaining that the orders given to Kemal Efendi by Istanbul on July 13 were not constructive and clear.

Finally, after the discussions, the German engineer Captain Stein and the Austrian engineer Captain Ivanovich arrived in Raguza, and the Engineers Commission convened in Raguza on July 15. As a result of the meeting , they decided to determine the borders based on the “de facto status quo” of 1856. The British, in particular, frequently emphasized that the commission’s duty was to determine the 1856 borders[ 61 ].

Another point of disagreement before the commission convened was whether there would be a member representing Montenegro in the commission. While the Ottoman Empire and Austria-Hungary opposed the representation of Montenegrins in the commission, the other members took a stance in favor of the Montenegrin commissioner being included in the commission.

The Prussians suggested that a German engineer participate in the negotiations on behalf of Montenegro, and even made preparations to send this engineer to Cetinje. While the discussions continued, the presence of Danilo’s Aide-de-camp M. Vukoviç, who came to Raguza to represent Montenegro, caused heated discussions between the Austrian commissioner Ivanoviç and the French and Russian commissioners.

In the discussion, the Ottoman delegate Kemal Efendi, who was ordered to remain silent in the face of the presence of the Montenegrin commissioner, supported the Austrian representative[ 62 ].

On July 28, the Ottoman Empire gave up its reservations about the Montenegrins being represented by a commissioner, but the Austrian delegate continued his protest. In response, when the other great powers announced that they had accepted the Montenegrin delegate, the Austrian Foreign Minister Count Boul sent an order to his commissioner to withdraw his protest.

The next day, the Ottoman Government accepted the determination of the border between the two sides based on the 1856 status quo[ 63 ]. The fact that a decision could be reached regarding Montenegro relieved Istanbul, and therefore the soldiers previously sent to the region began to withdraw, a mistaken decision[ 64 ].

The commission began its work on the de facto border on July 30, 1856 [ 65 ]. When the fieldwork began, the Ottoman Empire provided the commissioners with a sufficient number of tents and 60 guards, and in addition, many people who knew the region were assigned to assist the commission. After determining the status of the border, Mirliva Hüseyin Edib Pasha[ 66 ] was appointed as the head of the Ottoman engineers and the necessary technical equipment was sent to him[ 67 ].

In the commission of engineers, the Ottoman Empire was represented by Mirliva Hüseyin Edib Pasha, France by M. Hecquard, Russia by Staff Captain Vlangaly, England by Henry Churchill, Austria by Staff Captain Ivanoviç, Prussia by von Stein, and Montenegro by Vukoviç. Four positions emerged in the seven-person commission[ 68 ]:

1- The French and Russians supported the Montenegrin side

2- The British representative participated in the decisions taken by the French and Russians.

3- The Prussian representative remained neutral

4- Austrian representatives, who did not want Montenegro to grow too much, supported the Ottoman Empire[ 69 ]. They were especially against the transfer of Grahova to Montenegro. Austrian representatives defended the rights of the Ottoman Empire on many issues as if it were their own territory, and since they knew Serbian, they conveyed the confidential information that other representatives received from Montenegrins to the Ottoman representative Hüseyin Pasha. For this reason, Austrian representatives were rewarded by the Ottoman Empire and the officers were given medals according to their ranks.

The commission began by first dividing the areas to be mapped into fields. Then the commission was divided into two groups. The groups consisting of representatives of the Ottomans and the Great Powers carried out their own work independently of each other[ 70 ]. Then, the commissioners of the other states, accompanied by Montenegrin experts, and the Ottoman representative met at a determined place on the border and negotiated the border they had determined.

When the French and Russians wanted to realize their claims on Montenegro, these obstacles were tried to be overcome with Austrian support. However, the French commissioner insisted on the borders they had determined, and almost every time his word came true, and thus the border passed where the Montenegrins said it would. Ahmed Cevdet Pasha explains how this was done as follows[ 71 ]:

“Koç district is divided into two parts, namely Zîr and Bala. In the determination and limitation of the privilege line of Montenegro by means of a mixed commission, the testimonies of the people of the parties were taken as the basis, and since the people of Koç were in a state of rebellion as they were subject to Montenegro at that time, the people of Podgorica could not come to the border, and only the people of Montenegro and Koç who were subject to them, according to the statements of the people of Koç, the definite border remained on the side of Montenegro and Koç on the side of Zir. However, the state commissioner did not confirm this.

The Vasovik district is divided into two parts, Zîr and Bala. When the border was demarcated by the commission of mixed borders to be a privilege line to Karadağ, Vasovik Bala was left on the Karadağlu side and Vasovik Zîr was left outside.

However, although the testimonies of the people of the side were essential in determining the borders, since the people of Gusine could not come to the border, the border was demarcated only on the testimony of the people of Vasovik, and this part of the border was not approved by the state commissioner…”

Montenegrin attacks on Albanians of Shkodra, Suzina and Ispiç

As Ahmed Cevdet Pasha beautifully described, the determination of the border caused new conflicts at many points. For example, the conflicts were still continuing in 1864 due to the division on the Ispiç side of the border. Because half of the Suzina pasture in Ispiç was given to the Montenegrins and the other half to the Shkodra people.

However, the Montenegrins attacked continuously to seize the land on the Shkodra side, thus frightening the local people and aiming to seize the entire pasture. They even disturbed the people with rumors such as “Suzina will be left entirely to Montenegro” , and the Suzina people who believed the rumors even submitted petitions to Istanbul to prevent this situation. It was Ahmed Cevdet Pasha’s duty to calm the people and reveal that the rumors were not true[ 72 ].

As a result of the rather controversial negotiations, the most difficult part of the border, the Grahova-Benan section, was determined at the beginning of August. On August 10, the Zupa and on August 11, the Derbenak border works were completed and the Taşlıca direction was reached[ 73 ].

Mujo Ajvazovic and Ago Ljuca of Nikşiç

This region was indeed controversial. Because the Muslims (Albanians) of Nikşiç saw their own existence in danger if Zupa was left to Karadağ. Mujo Ajvazovic and Ago Ljuca from the Muslims of Nikşiç voiced the people’s reaction by saying, “We do not want to draw a border between Nikşiç and Zupa .” However, they could not prevent Zupa from being left to Karadağ[ 74 ].

The border determination commission completed its field work on August 24 and returned to Raguza, where the commission office was located. However, a final map could not be agreed upon in Raguza either[ 75 ].

The works carried out on the Montenegrin border were first called “tanzimnâme” , but in September the term “taḥdid” began to be used[ 76 ]. Even this expression used in official correspondence is important in terms of showing the point that the Ottoman Government had reached in six months.

The financial crisis that the state was in and more important problems such as the “Memleketeyn Question” played a major role in this transformation in the Ottoman Government. In order to solve the problems, the Ottoman Minister of Foreign Affairs Mehmed Fuad Pasha went to France, which opposed the Ottoman Government in every respect, and met with the French Minister of Foreign Affairs Count Valewski[ 77 ] and Emperor Napoleon III. However, the meetings were not successful.

Because Count Valewski asked Fuad Pasha not to exaggerate the Grahova and Kolašin incidents, while the Emperor only listened to the Pasha. According to Fuad Pasha’s report, the French believed that the Ottoman authorities were exaggerating both incidents. On the other hand, Fuad Pasha stated that even if it is accepted that the local people and the people of Kolašin exaggerated the events after Grahova, the Montenegrins cut off the ears and noses of the captured soldiers and sent them away, and that this alone would be an example of the savagery of the Montenegrins.

However, the French did not change their opinion about the Montenegrins, on the contrary, they gave Danilo 30,000 francs in aid and invited him to Paris[ 78 ].

C- ISTANBUL CONFERENCE AND SIGNING OF THE MONTENEGRO BORDER PROTOCOL

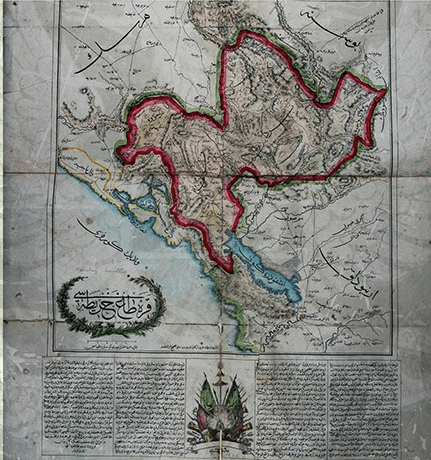

During the studies, the question of which side Grahova, Zupa and Kuchi Drageli would be on posed a major problem. Thereupon, a map was prepared by the French Staff Captain M. Gelis, and the Bosnian claims were marked in green and the Montenegrin claims in red[ 79 ]. The prepared map was signed by seven members of the commission on September 4 and presented to the Ottoman Government on September 15[ 80 ].

However, the French had Gelis prepare a third map containing a middle ground formula between the two sides and sent it to Istanbul. The French map took into account the Montenegrin claims regarding Grahova and Zupa, and the Ottoman claims regarding Kuchi Drageli. The British, French, Russian and Prussian representatives also supported the borders indicated on Gelis’ second map[ 81 ].

At the beginning of the negotiations, the Ottoman Government reiterated its view that the border should be arranged according to the status quo of 1853 in order to prevent these regions from being ceded to Montenegro. However, in the face of pressure from France and Russia, who would recognize Montenegro’s independence and even give it an exit by sea in case of rejection of the 1856 status quo, the Ottoman Government was forced to reluctantly accept the 1856 status quo[ 82 ].

After the Ottoman Government accepted the 1856 status quo, the conference began on 14 October 1858 under the presidency of Grand Vizier Mehmed Emin Âlî Pasha and the assistance of Minister of Foreign Affairs Mahmud Nedim Pasha[ 83 ].

The Ottoman representatives tried very hard to include in the protocol the articles containing the sovereign rights over Montenegro, in addition to the lands to be left to Montenegro on the border line, but they were unsuccessful. During the discussions, the Austrian delegate Ludolf supported the Ottoman side, while the British and German delegates abstained, and the French and Russian representatives strongly opposed the Ottoman proposal.

The negotiations came to a breaking point due to the strong opposition of the Russians and the French. After the Russians and the French declared that they were ready to recognize the independence of Montenegro if the discussions were prolonged, Âlî Pasha withdrew his declaration on the sovereign rights of the Ottoman State, this issue was frozen, and only the provisions related to the border were included in the prepared text[ 84 ].

The preparation of the protocol text was completed on 4 November and the approval of the Ottoman side was awaited[ 85 ]. The text was written in accordance with the request of the French, and Grahova and Zupa were left to Montenegro. With the acceptance of the French offer by the Ottoman Government, the conference ended on 21 Rebiülahir 1275/8 November 1858 and the Montenegro border protocol was signed.

The protocol was signed on behalf of the Ottoman side by Grand Vizier Mehmed Emin Âlî Pasha, Minister of Foreign Affairs Mahmud Nedim Pasha, President of the Tanzimat Council Mehmed Rüşdü Pasha, Ludolf on behalf of Austria, Thouvenel on behalf of France, Bulwer on behalf of England, Eichmann on behalf of Prussia and Butenef on behalf of Russia. The agreed text is as follows[ 86 ]:

“With the approval of His Majesty the Sultan, on the one hand, the Grand Vizier, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Sublime Porte and the President of the Tanzimat Council, and on the other hand, the representatives of the Austrian, French, British, Prussian and Russian states, within the framework of the instructions given to them by their respective governments for this purpose, came together to hold discussions on the continuation of the status quo on the borders of Albania, Herzegovina and Montenegro, which had existed since March 1856, and decided to convene a local commission on this subject.

At the end of this meeting, it was decided that it would be appropriate to add a map indicating the borders in question with red lines to the minutes prepared with the signatures of the participants. A copy officially approved by the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Sublime Porte would also be given to each representative.

At the same time, it was agreed that a commission of engineers, to be formed by the governments of the great powers, would personally go to the borders of Albania, Herzegovina and Montenegro, and fix the borders by placing boundary stones until next spring, and that the determined borders would be drawn and indicated on the attached map.

However, if this commission wishes and deems it necessary, it may also consult with the elders of these countries and reach a decision on the changes that have occurred in the territories (borders) of these places. In this case, they will determine the border between Upper Vasovik and Lower Vasovik[ 87 ] and the actual location of Kolašin by marking them on the map. It should be understood very clearly that this division will in no way interfere with the private property of either the individuals or the villages located on either side of the border.

Any differences that may arise on this issue and issues that cannot be resolved by the parties concerned will be examined and referred to the discretion of the commission responsible for the placement of the border stones. The real owners will be free to decide whether or not to continue to dispose of their property and rights by paying all taxes and fines, just like the local people, within the specified period, or they will leave their property and rights to the fair decision of the said commission.

As can be understood from the text, the Great Powers recognized Montenegro “de facto” , but not “de jure” [ 88 ].

D- IMPLEMENTATION OF THE BORDER PROTOCULUS

After the signing of the protocol, maps containing the new border were first printed. These maps were sent to the relevant units, primarily military institutions[ 89 ]. Then, in accordance with the decision taken in Istanbul, a new commission was established and the erection of the border stones began in the spring of 1859. The Minister of the War Department Hüseyin Pasha, who was on duty in the map-drawing commission, was appointed as the Ottoman delegate to the commission for the erection of the border stones on March 7, 1859[ 90 ].

With his appointment as commissioner, other countries made their own appointments[ 91 ]. 50,000 kuruş were allocated to Hüseyin Pasha, 15,000 kuruş to his assistants, and 10,000 kuruş to Anton Efendi, who would accompany the pasha[ 92 ]. A budget of 100,000 kuruş was allocated for the erection of the border stones. However, since the state budget could not cover this amount, it was decided to take out a loan[ 93 ].

In fact, since Hüseyin Pasha could not be paid when he first started his duty, he had to borrow 1,500 Hungarian gold coins from the Ottoman consul Monsieur Persiç in Raguza. The necessary money was paid by borrowing from Komodo, a Galata banker[ 94 ]. After the completion of the bureaucratic procedures regarding Hüseyin Pasha’s appointment, the Herzegovina Army Commander İbrahim Derviş Pasha, the head of the border determination commission and the Bosnia Inspector Kemal Efendi, and the governors of Shkodra and Herzegovina were sent a map of Montenegro indicating the new borders, and the regional administrators were informed about the work to be done[ 95 ].

The members of the commission, headed by Hüseyin Pasha, gathered on 18 April 1859 and began work on determining the final border line. At the same date, Ibrahim Dervish Pasha also transferred some of the forces under his command to Bleke in order to carry out the border works properly[ 96 ].

Since the work was not progressing rapidly, the first commission was abolished in July[ 97 ] and a new commission was established in August. Each country also appointed a commissioner to this commission. The Austrian commissioner Ivanoviç, the French commissioner Hecquard and the British commissioner Cox continued their duties; however, the Ottoman, Russian, German and Montenegrin representatives changed. Sefvet Bey was appointed as the Ottoman representative, Pedroviç as the Russian representative and von Lichlanberg as the Prussian representative[ 98 ].

The Ottoman State allocated 1,000 kuruş as a travel allowance[ 99 ] to its own delegate Safvet Bey and 150,000 kuruş to be used in the border determination work[ 100 ]. As in the appointment of Hüseyin Pasha, an order was sent to the governors of Herzegovina and Shkodra requesting that all kinds of assistance be provided to Safvet Bey[ 101 ].

Safvet Bey reached Trebin on 10 September 1859, met with Derviş İbrahim Pasha on 12 September and received information about the previous border determination works, and went to Koryaniçe on 13 September and started the actual works[ 102 ].

In the order given to Safvet Bey[ 103 ];

1- No property belonging to individuals on either side should obstruct the determination of the border.

2- Strict compliance with the protocol signed in Istanbul

3- Solving the problems that arise while drawing the border immediately on site

4- All issues that are expected to disrupt the peace of the country and the solutions to prevent them should be reported in writing through the commissioners.

5- If no petition is received regarding the lands on the border and no situation occurs that will directly violate the public order of the country, the border determination and commission work will be considered completed.

The work of the new commission was as follows: First, six commissioners would come together and determine the points where the stone would be erected according to the map drawn by the previous commission. After determining where the border stone would be erected, the latitude and longitude of the location where the stone was located were determined and recorded, and the information on which the border stone was erected there and from whom information was obtained were noted next to the relevant place in a report.

This work was carried out with the same meticulousness for each border stone[ 104 ]. Decisions were made unanimously, which caused the work to be delayed. In disputed areas, the border was not marked and the problem was moved on to the next work area to be resolved in the future. Especially strategically important areas were the subject of serious discussion.

For example, when determining the border around Klobuk, Safvet Bey tried to ensure that the border passed 3 km away from Klobuk Castle, while the Russian and French representatives tried to ensure that it passed 1,400 m away. The fact that the border passed 1,400 m away from the castle meant that Klobuk Castle would remain within the range of the Montenegrin cannons, meaning that the castle would lose its function.

When the Russian and French commissioners did not back down despite Safvet Bey’s objections, Safvet Bey also protested the situation. In response, the French commissioner accused Safvet Bey of obstructing the border works and threatened to complain about him to Istanbul. The attitude of the Russian and French commissioners became even more uncompromising, especially in determining the borders of the area surrounding the Duga Strait, which was Nikşiç’s only supply route.

Because both commissioners insisted that their own statements be followed, claiming that the weather had been rainy when the region was being mapped a year earlier and that the map had been drawn haphazardly for this reason. They aimed to bring the Montenegrin border as close as possible to the Duga Strait.

The Duga Strait of Nikşiç (Niksic)

In this way, the Duga Strait, which was already frequently attacked by the Montenegrins, would be closed at any time and Nikşiç’s position would be jeopardized. As can be understood from the attitude of the Russian and French commissioners, they made interventions that would pave the way for the indirect takeover of regions of strategic importance for both sides, such as Klobuk, Nikşiç, Kolašin and Isbuzi, by the Montenegrins or that would create new areas of conflict in the future[ 105 ].

When the works were about to end, the Montenegrins took action to seize the land between Isbuzi and Podgorica[ 106 ]. The Montenegrins claimed that there were some places belonging to the Montenegrin Piperi tribe in the Mali Berdo and Veli Berdo mountains between the two cities and wanted this region to be left to Montenegro. If the Montenegrin proposal was accepted, the connection between Podgorica and Isbuzi would be cut off, and thus it would be indirectly included in Montenegro[ 107 ].

When the Montenegrin demands were heard in Isbuzi, the people protested the border determination works and expressed their concerns[ 108 ]. As a result, the Ottoman-Montenegrin border passed only 1,000 steps from Isbuzi, and the coppice forests of the Isbuzi people remained on the Montenegrin side[ 109 ].

The population of Nikşiç, Trebin, Kolaşin and Taşlıca

The border determination works naturally made the Muslim people living in the region very uneasy[ 110 ]. In fact, the people of Nikşiç, Trebin, Kolaşin and Taşlıca expressed their uneasiness by sending two people named Mahmud and Mehmed to Istanbul. Thereupon, the Sublime Porte issued a declaration stating that no one would be victimized regarding the people living on the border.

Mahmud and Mehmed Ağas were given two thousand kuruş allowances each and sent back to their hometowns[ 111 ]. The Muslims were right to be uneasy. Because the commission usually ruled against them. For example, after the Montenegrin attack, in Koryaniç, where 57 Muslim and 12 Orthodox households remained, the lands of 84 people were left to Montenegrin by the decision of the commission[ 112 ].

The most important problem during the drawing of the border line was the land and real estate belonging to Muslims on the Montenegrin side. In order for this situation not to create problems for the public, the price of all kinds of goods in those regions was paid in advance. It was planned to sell the products of the disputed areas in auctions to be organized by a three-person commission appointed by the Governor of Shkodra, the Vladika and the consuls.

However, as soon as this issue was heard, the Montenegrins plundered the disputed areas and ended the problem before it started, and the state had to pay compensation to the owners of the products[ 113 ]. The foreign representatives, who were quite tolerant about the Montenegrin attacks, did not show the slightest tolerance to the Ottoman officials.

For example, the French consul in Shkodra, who was disturbed by the cannon fired by the Ottoman officials as a celebration for the completion of the border determination work, escalated the incident and personally complained to the Ottoman Minister of Foreign Affairs. According to him, this action could provoke the Montenegrins and lead to new conflicts[ 114 ].

The border determination work was completed at the beginning of November and the commissioners went to Raguza to draw the final map on 10 November 1859[ 115 ]. While Safvet Bey was working on the map with the commissioners in Raguza, the French consul Hefar was disturbed by Safvet Bey’s sensitivity in protecting the interests of the Ottoman Empire and spread the rumor that he had met with Istanbul for his dismissal, that his application had been accepted and that another commissioner would be sent in his place[ 116 ].

In this way, Hefar tried to upset Safvet Bey and break his resistance, but he was unsuccessful[ 117 ]. The preparation of the map, on which all representatives agreed, was completed on 2 February 1860 and approved by the commissioners[ 118 ].

The commissioners worked in Raguza until the beginning of March and on March 6, 1860, the commissioners of five countries sent a telegram to Istanbul stating that their duties were about to end, that only the disputed lands remained and that this problem should be resolved by the Governor of Shkodra, Abdi Pasha[ 119 ].

The request was examined on March 26 with the participation of the consuls of five countries under the presidency of Fuad Pasha and it was concluded that the commissioners had fulfilled their duties properly. On April 17, 1860, the consuls of five countries came together in Istanbul and decided to end the duty of the commission based on the decisions of March 6.

The decision of the consuls was approved by the parliaments of each country separately, thus effectively ending the commission. For example, the decision to end the commission was approved by the British parliament on May 9[ 120 ]. Thus, the determination of the border of Montenegro was completed. As can be seen in Maps 3 and 4, during the determination of the exact border, border marks were placed at 83 places[ 121 ].

During all the work, Austria was the only country that gave direct support to the Ottoman delegates. For this reason, the Ottoman Government awarded a fourth-rank medal to the Austrian commissioner in charge of the border determination commission, Jel Kristianovic, as it had previously done to Austrian officers who had shown service[ 122 ].

ESTABLISHMENT OF THE EQUIVALENT LAND AND REAL ESTATE COMMISSION

The border change was both a costly and sensitive issue. For example, during the border determination in Nikşic, the lands of 120 households remained on the Montenegrin side. 1,886,900 kuruş was required for the compensation of these lands alone. Some Nikşic families migrated to Bosnia because they did not feel safe. Thus, the Muslim population living along the border began to lose power[ 123 ].

When the lands on the border caused problems for both sides, Pasko Vasa Efendi, the government translator on duty at the Shkodra Governorate[ 124 ], was sent to Cetinje at the beginning of October 1860. As a result of Vasa Efendi’s negotiations, Vladika Nikola also stated that he was willing to solve the border problem, and thereupon a new commission was established to resolve border disputes only[ 125 ].

Both sides nominated five people to the commission. The Ottoman side in the commission was represented by the Sixth Şişhaneci Battalion Major of the Imperial Army Ali Efendi, Ülgün Director Raif Efendi, Vasa Efendi, Hafız Bey and Mahmud Ağa from the local population; the Montenegrin side was represented by Kapudan Maşo Vrbiça, Kapudan İlya Menaç, Serdar Povo Yuçavik, Serdar Bro Stanovik and Pol Dimitriyevik.

Following the establishment of the commission, an instruction was sent to the members of the commission on what to pay attention to. The instruction later formed the basis for the Cetinje Agreement signed between the Ottoman Empire and Montenegro on May 3, 1864, and the Istanbul Protocol signed on October 26, 1866 [ 126 ]. The instruction in question is as follows [ 127 ]:

1-a- It is not possible to change the previously determined border.

b- The properties of people or villages on both sides of the border will not be touched.

c- If the disputed areas that arise between the two parties cannot be resolved according to customs, the current owners of a property may keep their property on condition that they pay taxes like the other people of that locality or they may abandon the properties in their possession in return for a price to be determined fairly by the commission. The final decision on the status of these lands will be made after the commission examines them.

2- Those who abandon their real estate and land with a price to be determined by the commission will be able to buy real estate on the other side of the border or if there is an ownerless real estate belonging to the state, it will be given to them regardless of whether they can afford the price. However, it should not be concluded from this sentence that the land and real estate remaining on the Montenegro side will be left to them free of charge.

Special care will be taken to ensure that the real estate owners do not suffer any loss. However, the amount of the price to be given to those who want to sell their lands within Montenegro and the suitable lands to be given to those people on this side of the border will be investigated, the situation will be reported to Istanbul and action will be taken according to the response received.

3-a-The parties will be represented in equal numbers in the commission.

b- The commissioners will examine the border together and visit the disputed areas in person.

c- In order to prevent foreign countries from interfering with the activities of the Commission, it will be declared that the Sultan’s blessing is also valid for the Montenegrins.

d- If people who own property in disputed areas apply to the commission, the cases will be heard in accordance with justice and fairness.

4- Expert witnesses (erbab-ı vukuf) from the parties will be invited to the commission to determine which party has the disputed land and real estate along the border. However, in this case, care will be taken to ensure that the witnesses are as impartial as possible.

5- The commission members will report the decisions they make to the surrounding administrators and the Montenegrin side. These certificates will be prepared in Turkish and French, since the Montenegrins do not know Turkish. All commissioners will sign the certificates.

6- Since the people of both sides are not calm and there has been friction between them for a long time, the border arrangement was made for the comfort of both sides. Since a part of the state land will be left to the Montenegrins, the problems that will arise will be solved amicably and the issue will be reported to the center.

7- Books will be prepared for those who sell their real estate and land, by determining the product prices of the land to be left on the other side, and the annual prices of places such as coppices and meadows, and taxes will be collected accordingly.

8- Those who do not sell their properties but intend to operate them themselves will be taxed according to the rules of the party in which their property remains.

9- Commission members will be given a daily allowance by the state, and nothing free will be requested from the public.

10- As a result of the negotiations between the two parties, the security of the commissioners has been ensured. However, if necessary, three or five people may be assigned as escorts by the district directors.

11- Maximum attention will be paid to protecting the interests and dignity of the state in the work to be carried out.

The commission met in Vir Village on October 21, 1860 and began its work[ 128 ]. However, at the very first meeting, the Montenegrins agreed to include the disputed lands in Montenegro and the Ottoman commissioners did not agree to this, which caused a dispute between the commissioners of both sides. Therefore, the work was interrupted from the very beginning[ 129 ].

Montenegrin attacks on Nikşiç and İşbuzi continued after the failed commission

After the commission failed, the Montenegrins increased their attacks to seize the disputed border regions such as Nikşiç and İşbuzi. The fuse of new conflicts was ignited when the Montenegrins attacked a grain convoy heading to İşbuzi with a force of 10,000 people on February 21, 1861.

While in previous attacks, civil and military authorities were asked to be careful or to remain on the defensive, an immediate response was ordered to any attacks that would take place after the İşbuzi attack[ 130 ]. In August, discussions began on a military operation against Montenegro[ 131 ].

CONCLUSION

It was unrealistic to draw a definite border between the two sides. As can be seen from a journey from Podgorica to Cetinje or Niksic in today’s Montenegro, the plains, lakes and rivers are on the Ottoman side, while the mountainous land from Kotor to Niksic is on the Montenegrin side. It is understood from the attacks they made on the surroundings while the border stones were being placed that the Montenegrins would not accept these borders.

Nevertheless, the Montenegrins benefited greatly from the arrangement, increased their territory by 1,500 km2 to 4,400 km2 [ 132 ], implemented a policy completely independent from the Ottoman Empire within the borders determined in 1858, established their own legal and military system and finally declared war on the Ottoman Empire in 1878. Therefore, it would not be wrong to claim that with the 1858 arrangement, an independent state emerged, not politically but de facto.

Although the Ottoman authorities did not accept it, the foundations of a new state were laid with the drawing of the map indicating the border lines. Because in the Gotha Almanach of 1861 , Montenegro was shown as an independent country right after Mexico, and a short two-page note was made about the country’s history[ 133 ]. However, until the previous year, Montenegro was mentioned as a region governed by the Petrovic family under the title of Turkey[ 134 ].

On the map prepared by Kiepert in 1862, Montenegro was shown as a principality[ 135 ]. Vladika Nikola also began to refer to himself as a prince[ 136 ]. Traces of this approach can also be seen on the Montenegro map prepared by the Ottoman Empire[ 137 ]. The status discussions would continue until the Treaty of Shkodra, signed as a result of the Ottoman military operation in 1862.

After the military operation of 1862, Montenegro, which was previously shown as an independent country in the Gotha Almanach , was included under the title of the Ottoman Empire again. The authors of the almanac stated that Montenegro had been shown as an independent country in previous years, but that the region was part of the Ottoman Empire[ 138 ]. However, both during and after the Treaty of Shkodra, the Ottoman Empire and other countries would respect the borders of 1858. Even in the Ottoman documents themselves, the region was referred to as the Montenegro Hatt-ı İmtiyazı from 1858 until 1878, when Montenegro gained its independence .

Reference