Written by Petrit Latifi. Saxed from Vladimir Stojančevićs “Историјски часопис 7 (1957), Istorijski institut”.

In the history of European Turkey at the beginning of the 19th century, the Arbanas movements in northern and southern Albania and the neighboring areas of Old Serbia, Macedonia, Epirus and Thessaly played a significant role. Of all these movements in the 1820s and 1830s, the most significant were those that remained linked to the names of Ali Pasha Janina and Mustafa Pasha of Shkodër.

Although largely incorporated into the political and military history of the Turkish Empire itself, they remained marked as movements of two prominent Turkish pashas of Albanian origin, and therefore as crusades more closely related to the Albanian historical past. But while the historical activity of Ali Pasha Janina was limited and localized far in the depths of the Balkan Peninsula and was more closely related to the history of the liberation of Greece and the history of the seven Ionian Islands than the political neighbors, until then the movement of Mustafa Pasha of Shkodër came into more frequent contact with the states of Montenegro and Serbia, then with the Bosnian Muslim movement of Husein-Captain Gradaščević, and that is why, unlike the first, both of them have a stronger place in Serbian historiography.

Because of all this, the natural interest of the researcher of the Serbian past could not, at the same time, look at some of the basic facts and phenomena that also related to northern Albania, with which both the Montenegro of Peter and Peter II Njegoš, and the Serbia of Prince Miloš, through the confluence of circumstances and the historical development of political relations on the Balkan Peninsula, came to closer or more frequent mutual connections.

Hence, the knowledge about the Albanian past of the period of sudden rise and unexpected rapid collapse of Mustafa Pasha Bushatlia in 1828-1831 is perhaps the most well-known and historically most reliably presented precisely in the works of Serbian historians and Serbian historiography.

In contrast to this, the period that followed him remained known only for the many details scattered in the general problems of Turkey at that time, and not connected into a single historical picture and historical characteristic of a wider scope. It is known, however, that the era of large-scale reform projects of the central Turkish administration and bitter resistance of the conservative and rebellious Muslim feudal-hereditary lords of Bosnia and Albania in the 1820s and 1830s proved to be of great political importance in terms of integrity the Turkish empire in the Balkans, as the Serbian and Greek revolutions proved, on a much larger scale and with great force of consequence in further historical development.

However, unlike the Serbs and the Greeks, the Arbanasis did not lead to a situation in which they freed themselves from Turkish rule in their movements. However, it is interesting for historical research to present the basic moments and events of Albanian-Turkish relations from that era as a fragment not only of Albanian history, but also as a detail of wider importance in the Balkan history of the thirties of the 19th century.

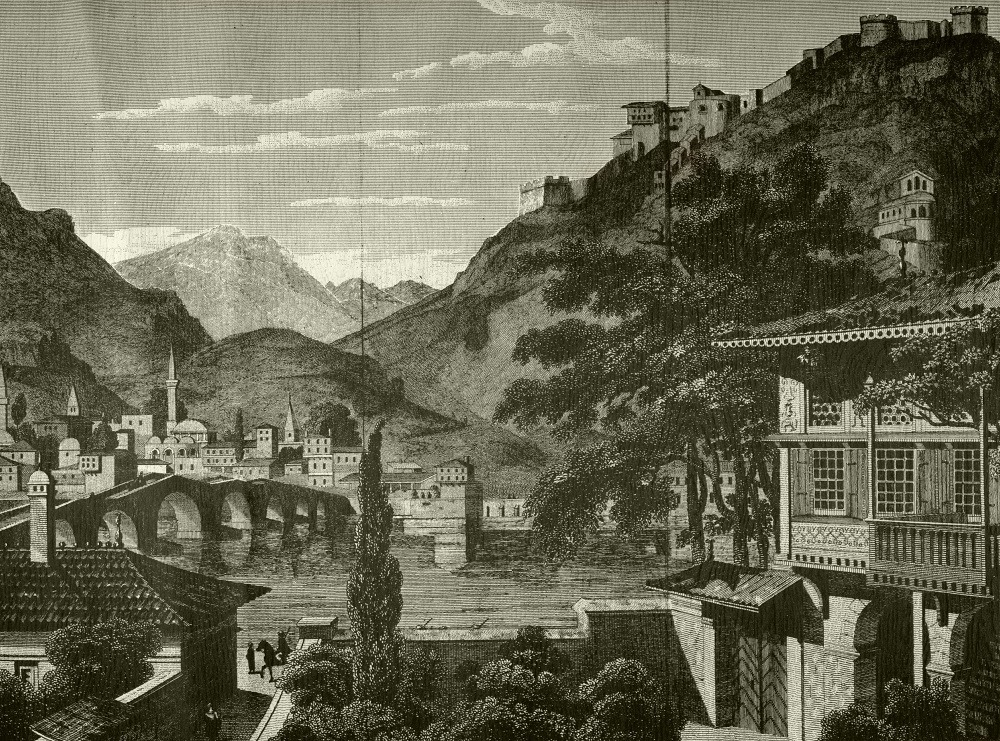

Military breakdown of the hereditary Pasha of Shkodër in the title of Vizier, Mustafa Pasha of Shkodër in 1831. led again to the complete establishment of the central Turkish authority in the whole of Albania. At the beginning of November of that year, Mustafa Pasha was forced to surrender and forcibly transfer to Constantinople, and the leader of the southern Albanian regions, Silihdar Poda, still during the fighting, went over to the side of the army of Grand Vizier Mehmed Reshid Pasha and then took part in the battle for Shkodër.

The Shkodër Pasha, which during the Russo-Turkish War of 1828/29, due to the participation of Mustafa Pasha, was enlarged by Dukagjin, Elbasan, Dibra, Ohër and Tregovishte, then by Kruja, Kavaja, Durres, Tirana and Ulqin, was again reduced to its old borders. How before that, in 1830, the other two main leaders of southern Albania, Veli-beg and Arslan-beg, were liquidated. and the last hope that the Turkish power, which was energetically established in the rebellious regions by the courageous Grand Vizier Mehmed Rešid Pasha, could be easily removed again in the near future.

Buying weapons and taking Arbanas into the Turkish regular army, the main motives of the Arbanas movement against the sultan under Mustafa Pasha of Shkodër, now began to be introduced as a novelty among the Arbanas.

In March 1832 Namik Ali Pasha, the former Bosnian Vizier, was appointed Vizier of Shkodër, and Kara Mahmud Pasha Vizier of Bosnia. As, after that, the Porta thought to punish the Montenegrins for their friendship towards the deposed Mustafa Pasha, and for their attack on Shpuz, Zhablak and Podgorica in 1831, the new Shkodër vizier Namik Pasha led an offensive against Montenegro as well.

But in this campaign, the Montenegrins terribly defeated the Turks, and the new vizier retreated to Shkodra. This time, the northern Albanian tribes Klementi, Hoti, Grudi, Kastrati, stood in solidarity with the Montenegrins, not participating in the Turkish army. This unexpected Turkish defeat in the battle with Montenegro meant that the authority of the Shkodër vizier was lost at the very beginning of his reign, especially in Shkodër, its immediate surroundings, and in Malesia.

The inappropriate way of administration that Namik Ali Pasha introduced in northern Albania, in addition to the already mentioned tribes, removed the influential beys from the Shkodër area, accelerated his failure, and then led to his downfall. In the writings of fierce skirmishes between the Vizier’s army and armed detachments of the Arban Begoons from Tabaki, Terci and Shkodra, the administration of Ali Namik Pasha was taken away in the town of Shkodër: Ali Bey and Yusuf Bey, from the Bushat family, as a kind of provisional government, took power in their hands, relying on, in addition to their brastvenik, also on three hundred zapgi of Hamzi aga, as the main protector-kulukibasha of Shkodër bazaar. Only the fortress remained under the control of the Vizier of Shkodër, which was protected by only one battalion of the regular army.

The duality of power on the territory of the Shkodër district, and the complete loss of control and administrative authority of the Turkish vizier over the entire territory of the Pashaluk, lasted for several months, during which time all economic life was paralyzed.

The unfavorable consequences of this, as a result of which the Christian merchants of the towns of Shkodër suffered in particular, led to the fact that an Albanian-Turkish town delegation went to Constantinople to ask the Porte to replace the unpopular vizier and to pacify the general situation, certainly keeping in mind the class of the urban population of Shkodër and of the feudal circles of its immediate surroundings. The special Porta commissioner who came from Constantinople, after this intervention, to investigate the conflict between Shkodër and the vizier, ended with Namik Ali Pasha having to leave Shkodër.

The overthrow of Ali Pasha among the population of northern Albania was received with great relief, namely, it spoke of the prudence of the Turkish central administration to, on the one hand, prevent the uncontrolled and improper abuse of power by one of its high officials and, on the other hand, to meet the legitimate wishes of its subjects. In practice, it seemed that the Drim plains, led by Mustafa Pasha’s relatives, relying on the opposition of the small Sor tribes to the Turks, would once again gain some political power. In great anticipation of the further development of the situation, the new Vizier of Shkodër, Hafiz Pasha, finally arrived on January 6, 1834. accompanied by his chief Naselnin Sherif-bey and 1,200 spahis.

The arrival of the new vizier in Albania and Shkodër, however, was immediately accompanied by an act that upset the Shkodër beys and Varosh baryaktars (“elders”): Hafiz Pasha, bringing in his new chehaya, dismissed from his service the former Ali Jashar Bey, from the Bushat family, and one of the resentment was an expression of distrust, which in a short time turned into a latent distrust towards the new vizier.

But in addition to this act of an administrative nature, the new vizier also tried to introduce innovations in the economic field, at the same time violating some of the rights that they had usurped for themselves immediately, during January, Hafiz Pasha banned the export of grain from Albania.

This ban, however, began to cause considerable damage both to the Albanian beys (who had it as their amount of natural rent) and the Shkodër traders-liferants, as well as to the Austrian importers, who mainly supplied some regions with Albanian grain of (Austrian) Dalmatia; this, in turn, had the effect of reducing the income of Albanian merchants on the one hand, and on the other hand had an effect on the price increase in Dalmatia.

The Austrian internunciator in Constantinople, Baron Stirmer, using the means of state diplomacy, intervened at the Porte asking for a piece for the material interests of his citizens. This case, then, was moved several times over the years, especially because of Hafiz Pasha’s attempt to raise export and import duties from 3 and 20%.

The new vizier continued his administration by implementing other energetic measures: he not only dismissed the old Ali Jashar bey from his service, but also kept him with him for a while as a guarantor in order to pay the debts that Ali Namik Pasha left behind to his creditors and suppliers.

Furthermore, for his own needs, he collected 50,000 piastres from Shkodër as an account of his vizier’s salary, immediately upon his arrival, informing the Porte that he had “discharged” the arrears of the vizier’s tax. With that, he also took on himself part of the obligation of the debt owed by his predecessor to several merchants from Shkodër.

In the province, Hafiz Pasha is approachable, but cautious, in the rapid introduction of his full power. He replaced Ibraim Bey from Kanaya, who was appointed as the sandjak of the same name by Ali Namik Pasha for one year, sending his treasurer there. However, Ibrahim Beg was supported by family ties from the beg from Tirana, and had strong support among the population of his region, the vizier’s treasurer did not go further than Durrës. The previous hereditary ajan of Podgorica was also replaced in his position by a vizier’s man, a Turk from Shkodër.

All these measures of the Vizier of Shkodër indicated that he began his reign with energetic endeavors, and that he had a certain political tendency, which was certainly pointed out in Constantinople.

But much more important than all this was the issue of disarming the Albanian population on a wider basis, then their introduction into regular Turkish military service. Hafiz Pasha certainly had an order from the Porte to partially implement the provisions of the tanzimat (“new order”) and to eradicate riots, certainly in the sense of the order of the great nezir Mehmed Rešid Pasha from 1832.

Enumeration of the population for the purpose of introducing them into regular military formations was the main measure of the tanzimat that the new pasha had in mind to carry out in Albania. According to Austrian official information from mid-May, Hafiz Pasha behaved wisely and tactfully in the administration, especially in negotiations with the arrogant beys.

But the Muslims of Albania were determined opponents of the sultan’s reforms and, as such, great sympathizers of Mehmed Alija’s struggle with the Porte. The possibility of Mehmed Ali’s renewed war with the Porte clearly indicated that the Arbanas would be on the side of the tsarist renegade. The very psychological favor of the Muslim Arbanas made it difficult, or could have made it more difficult, for the complete and permanent security of the Turkish administration in Albania. Indeed, when this conflict in the Levant began again, the Porta which needed a lot of troops and a lot of money to successfully fight from a gray and dynamic outlaw, actually Arbanas by origin, Hafiz Pasha ordered a certain requisition of cattle and monetary contributions, all with the intention of reinforcing Shkodër with new detachments of army troops.

This order, understandably, met with indignation in no time, and it was publicly said “how the inhabitants are firm in their decision to oppose even with weapons any innovations (recruits)”. All ranks of the northern Albanian population, beys, Shkodër barjaktars (“old men”) and citizens, opposed the implementation and, in particular, to go to Albania, remaining only with the fact that they hand over only a few hundred to the Porte.

On the other hand, according to the information received by the Austrians, the Shkodër locals were ready to oppose the entry of new regular troops into the city, not hiding their sympathy for Mehmed Alija’s administration in Egypt. Another delegation of citizens, after the case under Ali Namik Pasha, again went to Constantinople to arrange the issue of the introduction of tanzimat.

At the end of July and beginning of August, the three main elements of dissatisfaction in Shkodër were: 1) the appearance of new regular troops, 2) the introduction of new taxes, and 3) the announcement of recruitment for the Nizam.

The resistance of Arbanas forced Hafiz Pasha to constantly seek reinforcements in the army and armaments. The introduction of regular military service was particularly energetically opposed by beys and bannermen. Especially the beys, in order to make the Pasha’s intentions as difficult as possible, secretly supported the otherwise existing bandits and robber groups, and they only now, having powerful protection, indulged in murders and robberies on a larger scale not only in the villages, but also in Shkodër itself.

A general characteristic of the unbalanced and restless situation, could can be seen from the following statements of the Austrian vice-consul in Shkodër, Balarin:

“Jusuf-bey, having been removed from the position of commander of Zadri, no longer wanted to respond to Pasha’s calls.”

This was also done by the other beys who were removed from their positions, and according to the secret order of the aforementioned, four dozen dirty Morlaks disturb the houses in the villages, stealing whatever they can get their hands on. Almost the same thing is done by the inhabitants of Shkodër, who want to live at the expense of rural families. This new phenomenon is not communicated to the Pope, because people are afraid that they will be killed secretly. It seems that even some commanders of the market (bazaar) have a share in these corrupt actions, and they are beginning to turn a deaf ear to such crimes.

The roads and areas between Lezhë and Berat suddenly became very unsafe for all passers-by, and especially for merchants, foreigners and even foreigners. This powerlessness was even more intensified since, sometime (probably) in May, the people of Berac killed their muselim, and opposed the release some military detachments towards Shkodër.

According to Balarin, it seems that in this disorganization of public order and security, the beys of Berat Elbasan, Tirana, Kavaja and Ohër were involved in the agreement. And in the city of Shkodër itself, insecurity was also very high, since the beys helped problematic wanderers prone to mischief, blackmail, theft and murder.

This disorganization of public order was one of the elements that caused distrust towards the Turkish government, and resulted in an even stronger loss of its authority. Fiscal and financial measures of Hafiz Pasha met with particularly great dissatisfaction. In the financial administration, in addition to the monopoly of tobacco, scaffolding on Lake Shkodër, salt and gunpowder production, the vizier also banned the sale of wax, which again, as particularly interested, affected numerous Albanian beys.

With the previously mentioned ban on grain exports, and with increased export duties. import duties, this vizier’s intervention and control of the basic economic resources of the country, caused, with its disordered and disorganized public order, that the economic situation of the economically active Albanian areas of the narrower Shkodër district (kaze) and near the sea towns deteriorated to the extent of its complete restraint and stagnation of the nation.

It should be added here that the vizier, only for a while, completely prohibited the Montenegrins from getting grain from Shkodër and salt from the coastal regions under his rule. The moment of administrative control over a large part of the economy of the northern Albanian regions, expressed as a factor of economic coercion and economic management pressure, did not remain without effect and consequences in the sector of political relations of Arbanas towards the Turkish administration and its vizier in Shkodra. It was another element in a series of anti-Turkish sentiments towards the Turkish government.

Due to this development of things, the duel between the viziers and the beys imperceptibly went beyond the limits of their mutual conflict, and by including the urban population of Shkodër and other trading towns on the coast, it rather crept into the field of fierce opposition struggle against the vizier as a representative of the central Turkish government.

The general insecurity throughout the territory of the Shkodër Vizier’s Albania gradually became the work of the opposition mood of the majority of the population. Because of all this, the prospects that the provisions of the Tanzimat could be implemented successfully and peacefully became practically null and void. The situation could be improved only with the participation and presence of a large number of the armed forces of the Empire.

At the frequent invitations of Hafiz Pasha, the Porte finally decided to send a considerable military force to Albania. In the middle of June, two battalions of the new regular army (“militia”) had already arrived in Shkodër, and two more were expected. The news of their arrival caused great excitement among the people of Shkodër, since it was known that the maintenance of these troops would be a burden on the civilian population. Upon arrival in Shkodër, the new troops were poorly prepared in fortress, and along with them Hafiz Pasha also issued special orders marked in a firman.

During July, dissatisfaction in Shkodër was even more pronounced not only because of the presence of the newly arrived army, but also because of the introduction of some new levies (about the maintenance of the army), and because of the beginning of the recruitment census.

Yusuf-bey, the former commander of Zadrim, and a few other begons who had been dismissed from service by Hafiz-pasha earlier, rebelled completely from the government, still retaining the sympathy of a large number of the population. With new reinforcements, Hafiz Pasha sent one battalion to Durrës as support for his treasurer, and then ordered and bought provisions in Peja and Prizren. New reinforcements in the meantime continued to arrive. In August, 4,000 infantrymen, 2,000 horsemen and one company of Toshi with about 20 cannons came to Kavajë from Bitola.

Having just now received considerable reinforcements, Hafiz Pasha immediately started measures to liquidate influential opposition beys, who were certainly sympathetic to Mehmed Pasha of Egypt and, certainly, as was said, at least in a certain sense relied on his authority and popularity.

In addition, it was also necessary to force the obedience of “i principali signori dell’ Albania i quali (sono) contrari nella magior parte alle recenti inovazioni”, and who in their difficult-to-access mountainous regions were not easily forced to fulfill the imperial orders. Finally, the introduction of a stable order in Shkodër itself, which had declined so much recently, lay also in the midst of the activities of the newly arrived army.

Starting his venture, following the earlier action of Grand Vizier Mehmed Reshid Pasha, Hafiz Pasha first, for the purpose of demonstration, occupied the strategic hill of Tepe with three cannons and one battalion of the army, from where he could hold the town of Shkodër in check, and then two imprisoned mountaineers were publicly hanged in the market “reg commun esempio”.

Then the vizier proceeded to the main thing: the partial reading of the 24-point firman. In front of all the gathered bannermen (“elders”), he publicly announced two points of that firman by which Ali-beg, along with his families and movable property, were banished to Brus, Suleiman-bey with his brother and Yusuf-bey also with his brother.

The refugees were given only 24 hours to submit to the decision and prepare for the journey into exile. Until their answer, the vizier, as a surety and security, kept under guard all present flag bearers, except for two. When they refused to submit to the decision of the firman and made it known that they would flee beyond the border, the vizier ordered the houses of Suleiman-bey and Yusuf-bey to be burned in the bazaar, confined the “comme schiave” of their families in a barn, and imprisoned in the city all those bannermen who were friendly to the outlawed beys. One part of the army came down from the city, occupied the entrances of the bazaar and started to ensure order and trade

In such events, the population of Shkodër was convinced that the battalions came for security and the final implementation of “una coscrizione militare”. however, for that moment there was no access yet.

Approaching the energetic implementation of measures to strengthen the Turkish supreme power without poverty and legality, Hafiz Pasha could not do anything to the three beys who were sentenced to exile in Brus in absentia. According to a news report from the end of July, these fugitives were seen at the mouth of the Bojana on a small boat, for which at that time it was not known where they were going.

Only in the middle of August, Balarin informed the matin administration that these three were spotted near Corfu, so it was considered that they had headed for Egypt. A month after this, Balarin also reported that the fugitives had indeed been holding out for the state in Corfu for some time, and that Hafiz Pasha had asked the administration of the Republic of the Ionian Islands to hand over the fugitives to him as rebels.

The Republic, however, did not meet him, invoking the right of the London Parliament, under whose patronage it stood in political questions, to decide on this. After all these events, it was certain that the Northern Albanian beylirs, in the face of his main representatives, lost the battle, and that for a while he withdrew from the field of active political opposition.

Another event was just as interesting at this time, and it refers to some interroom among the Miridites, in which Hafiz Pasha also had a say. Namely, skilfully quarreling over the primacy and representation of the two Miridite fraternities in the Turkish government, he managed to make the institution of blood revenge take hold among them, and to bring discord between them for the first time. (Later, Hekar gave a more detailed account of the events surrounding this blood feud, which is also confirmed by archival data, i.e. reports sent by vice-consul Balarin from Shkodër).

This mutual Mirditë feud ended temporarily when Bok Doda, Alexander’s cousin, as was the case with his uncle, was imposed by the vizier as the commander of the quarreling and weakened Miridites. After Pasha’s intervention reconciled, 24 Miriditë elders, having the consent of all their tribesmen, together with the new commander Đok, swore allegiance to Hafiz Pasha and Porti.

This penetration of the central Turkish administration from Shkodër into the cells of the Miridite tribal organization, which were largely Christian, a procedure similar to Mehmed Repid Pasha’s attempt at the end of 1831, meant another victory for the Turkish Empire in Albania, and was not without significance for the future the consolidation of Turkish power among the Arbanas, especially in this period of revolts and uprisings.

It was natural, in such circumstances, that the new commander of Miridit, similar to 1831, the commander of Hoti confirmed by the Vizier of Shkodër, was one of the strongholds of the Turkish influence on these two powerful Arban tribes, and through them, to some extent and occasionally, also on other Malisor tribes.

After the defeat of the beys, and a part, the most powerful in fact, of the tribal organization of northern Albania, Hafiz Pasha achieved his full success in pacifying the Shkodër Pashalik. The citizens of Shkodër, the weakest of all the northern Albanian population groups, did not resist in the slightest after that.

After all this, Shkodër and its surroundings were completely calm. The army behaved well and paid its expenses, and it was considered that the Pasha wanted, according to the principle of legal but just administration, a normal and quick pacification of the irregular situation: by supplying everything from the side, the Pasha wanted to prevent the lawsuits of the townspeople in every way.

The only remaining uncertainty rested on the news that the vizier, having taken the situation completely into his own hands, would at any moment want to proceed with an energetic enumeration of those liable for military service, i.e., to enslave a certain number of Arban people.

The convocation of the pashas and beys, which Hafiz urgently ordered to communicate the latest orders from Constantinople, were a sure fact that this was finally being approached. At the beginning of December 1834 in Shkodër they were together: Pasha of Debra and Pekin with several beys of Debra, Elbasan, Ohrid, Ibrahim-bey from Kavaja, Abdurahman-bey from Tirana.

In particular, the appearance of Debar Pasha in Shkoder was interpreted as a clear fact that Hafiz Pasha’s new order was already on firm feet, since this native of Debra, in the eternally restless and independent Dibra, was important until now as a persistent and bitter opponent of the sultan’s reforms and new regimes. But the shepherds of Peć and Đakovica, over which the Porte extended the supervision of the Vizier of Shkodër some time ago, refused to come to Shkodër, not expressing any disobedience to the Vizier as a high official of the Sultan.

He acted in the same way on the next commander of Miridith. For this situation and for this moment, it was characteristic that now, even if in a roundabout form and under cover, the main role of the opposition against the Shkodër vizier passed to two Arban hereditary pashas from Old Serbia (Metohija) and to the most powerful tribal organization of Severia Albania-Miridite.

But the threats still took their toll, and these opposition members came to Shkodra at the end of December. During several days of talks, Hafiz Pasha read them an order according to which they all confirm their positions, but also submit to full authority and obedience to the Vizier of Shkodër. Then they started talking about providing soldiers for the imperial army “ed a ciascuno venne stabilito il contigente di recluta per contributeire all’ effetto”.

The Pasha of Pejë, Gjakova and the commander of Miridita protested against the vizier’s request to provide the necessary number of soldiers at their own expense and clothing. The Shkodër people were assigned to provide 500 soldiers, and Hafiz assigned ten days for all of them to gather recruits.

At the same time, as a sign of the goodwill of the central administration, it was considered that the sultan pardoned all the Shkodër locals who had previously been confined in Thessaloniki. Hafiz Pasha could, similar to Mehmed Reshid Pasha after the collapse of Mustafa Pasha of Shkodër, start introducing the provisions of the sultan’s tanzimat.

But the great uprising in the southern parts of Albania has now just taken the place of the suppressed uprising in the Shkodër pashalik. The center of this movement was the area around Berat. With its appearance and its development over several months, it had the effect that, on the one hand, the implementation of the measures of the Turkish central administration in the area of northern Albania was again suspended, and on the other hand, it caused a major military and naval action by the Turkish armed forces, which, for the third time in less than four years, once again strengthened the sultan’s power over the whole of Albania by force. The second great bombardment of Shkodër in June 1835, after 1831, together with the great armed battles between Arbanas and the Turks, were a direct consequence of the uprising around Berat.

The beginning of a new series of riots among the Arbans, according to the well-publicized news of the “Obštih Novina” from Trieste from the beginning of January 1835, seems to have come at the instigation of the agents of Mehmed Alija from Egypt. Although, at this time, it was still not certain whether the Arbans movement encompassed the entire country, or only the southern after all, the general belief was that the Arbanasis would not be satisfied with the Turkish administration, since the unrest here lasted for almost two full decades.

The main reasons for the instability of the political situation among the Arbans were: the disintegration and crisis of the feudal economy (in the territories of the Albanian beys in the plains and valleys of northern and especially central Albania), the penetration of the Turkish administration into the autonomy of the tribes, especially among the Malisors, the destruction due to frequent military campaigns of the city economy of Shkodër as the center of the economic life of a large part of Albania, replacement of the hereditary ayans of Ulqin, Shpuz, Podgorica with ordinary Turkish military officials.

Those elements of a political, economic and social character formed a situation of indeterminacy and stagnation both in the Albanian economy and in the social life of Arbanas, especially in matters of their local tribal self-government. But the same, to a large extent, was also true for the population of central and southern Albania.

According to the same report of “Opštih Novina”, “some rebellion was declared” in southern Albania, especially known Tafil-Buzi who operated with his squad in the vicinity of Berat, extending the scope of his action even to the borders of Epirus. Because of this situation, the Porte was forced to send one of its commissioners to Albania, whose task was to investigate the true state of affairs, and with the probable authority to influence the pacification of Arbanas.

The Turkish fleet, which made small preparations for departure from Constantinople, according to the news reaching the public, was certainly destined for an expedition to the Albanian coast, the news, however, which in the meantime and with a delay arrived from Albania to the Port, spoke of the capture of Berat by Tafil-Buzi, and of further expansion of the uprising. Although there was no accurate information, it was certain that the Turkish government in Albania was by no means sure of its stability.

Thus, according to a piece of news brought by Salvatore, the Toskë Albanians raised a general uprising and, taking Berat, marched towards Janjna and Bitola. This movement was supposed to have the character of a struggle for political independence, judging by the fact that it was said that a “legislative body” was in charge during the winter. The news also confirmed the influence and financial support that Mehmed Alija sent from Egypt to the Arbanas, as his natural allies in the fight with the central Turkish power in Constantinople.

Although independent of this influence, probably at the end of March, the inhabitants of the city and district of Elbasan also rose up to the uprising. According to some news reports, the citizens of Elbasan started the uprising by first expelling one and then killing another Turkish representative of the Shkodër vizier, allegedly because of excessive, violent beatings and a smaller fine.

The resistance of the Albanians, with the further development of events, seemed to have its center right here. The people of Elbasan, moreover, appointed one of their vassals as their commander (muselli), refusing to submit in advance to the new commander whom the Porte had already sent to them. On the contrary, having put the whole district under arms, the Elbasan people relied on Tafil-Buzi, the princes together with him revolted on the neighboring districts.

After the people of Berat and the people of Elbasan, almost the whole of Albania was in the movement, especially Ulqin and Shkodër with their surroundings. Although here, in the north, the causes and reason for the uprising were of a different nature, the uprising around Berat and Elbasan served as a reputation and an incentive.

According to the information that reached the Austrians at the border, the inhabitants of Derz, Tirana, Kavaje and the mountain tribes opposed giving Hafiz Pasha military help to fight the rebellion in southern and central Albania, unlike Podgorica, Shpuz and Baran who were in a constant border conflict with the Montenegrins, and hence they needed the support of the viziers. Dibrans also resisted the Pasha’s orders.

With this development of the political situation, northern Albania began to be at the center of events again. As the general cause of this new sudden movement in northern Albania, which created material grounds for general discontent and which completely paralyzed for a few months the complete efficiency of the Turkish administration, it was stated that the “upper” Arbanasi refused to pay the Porte 600 kesas (300,000 groschi) a year in the name of maintenance of the Turkish army in the (expanded) Pashalik of Shkadar, and according to some accounts, 75,000 groschi were allocated to the Shkadar for the construction of barracks in the town.

According to the news published by the Zadar newspaper at the beginning of June, the Pasha demanded that the Arbanas not appear with weapons in order to preserve order and order. In addition, he asked for 250 bags to finance repairs and maintenance the fortress of Shkodër, for the purpose of supplying Zhablak and Shpuz, and finally, the extradition of some criminals.

As the beys, led by Husein-bey Bushatlia, and the Muslim part of Arbanas refused the Pasha’s demands and responded with a rebellion, a two-day bloody conflict ended with the death and wounding of several hundred. Arbanas and the Turks.

To the horror of the merchant population (Christian and Muslim), the Pasha and his army occupied the market. During the rebellion of 5,000 peasants, Hafiz Pasha had 4,000 soldiers and 36 cannons at his disposal, which – while the fight was going on for a short time – bombarded and heavily destroyed the town of Shkodër. In this way, the rebels were also wounded from Shkodër, but they compensated for this loss by joining the rebellion of the militant Catholic Miridites and Ulqin people.

Fierce fighting took place in Drisht, in Zadrimë, in Tabaki, 50 In this last place in particular, there was a three-day bloodshed and street fighting from June 26-28, in which several hundred insurgents, citizens and soldiers again fell dead and wounded. The city of Shkodër, which as a result of the fighting was already “half-almost deserted” and besieged, began to suffer greatly from the scarcity of food.

The danger to the vizier was all the greater, as help arrived with great difficulty, and the people of Shkodër joined the people of Ulqin, while the arrival of new ones was also expected. The situation of the defenders of the fortress was made more difficult by the fact that all the bridges on Drin were destroyed, and that the Miridites had, at a special meeting, promised to kill anyone with their entire family, and to ravage his property with fire and sword to anyone who proved that the besieged sultan’s army had been wounded.

Other Malisor tribes intended to, by helping the Shkodër people, force the vizier to surrender and capitulate by siege and starvation. Very angry because of the dead and the destruction, the insurgents publicly asked the city crew to hand over the surrender of the vizier, on whom they thought they would take public revenge.

In the meantime, Porta had invited all pashas of Rumelia and Albania to move to Shkodra, and appointed Pasha of Trikala and Larissa, the son of the former Grand Vizier Reshid Pasha, as commander. 57 Serasker led 800 soldiers, the pasha of Debra was supposed to prepare 1,200, and the beys from Pećin, Mata, Tirana and Kroja and irregular troops from Teto’s pashaluka were supposed to go to Lješ via Elbasan and Tirana.

During the first half of August, fierce battles were fought around Lezhë and Shkodër. During that time, the Turkish fleet was also in front of Durrës, and at the end of August, it landed 900 soldiers in Lezhë and a small army in Tivar. During that time, suddenly, before the onslaught of the imperial army, the uprising around Berat and Elbasan was very quickly suppressed.

But the uprising of the north Albania, less fragmented by feudalism and stronger tribal organizations, lasted much longer. While the fighting was going on around Lješ, the kanci-basha of Rumeli valija Suleiman-ag came to Shkodra, but his mission in negotiations with the insurgents did not end completely successfully.

While the army of the Rumeli Wallia was gathering and moving towards Shkodra and Lezhë, Vasaf-Effendi, the son of Hai Bey Pertef-fendi, as the Sultan’s new secretary, personally went to Shkodra to “soí proprii occhi” inspect the situation. It seems that his arrival, if it did not quieten down, at least prepared for the gradual calming down of the uprising.

The move of the imperial troops forced the insurgents to withdraw and capitulate. In the second half of September 1835, the Grand Vizier was already free from the blockade, and sent the parliamentarians to the insurgents to lay down their arms fourth, by the gift of the Austrian vice-consul. Many of the beys laid down their arms one after the other.

However, it is interesting to note that on this occasion a delegation of merchants from Shkodër begged the Grand Vizier to unblock the Adriatic coast, which he promised to do within ten days, according to the agreement with Vice-Admiral Ahmet Pasha. In order to psychologically influence the cessation of resistance, the grand vizier promised to conduct a survey on the correctness of Hafiz Pasha’s management of the pashaluka in the presence of the flag bearer and Vasaf Effendi.

At the end of September and the beginning of October, with 10,000 regular soldiers and about 4,000 irregular troops in Shkoder, Lezhë, šDurrës, Kavaja, Elbasan, the Grand Vizier was the complete master of Albania. By the middle of October, peace was fully established, the coast was unblocked, and commerce was given the possibility of free development and traffic.

As a result of this great military campaign of the imperial army and its military successes, as well as political negotiations with the Arbanas, Albania settled under the main condition: that the Arbanas recognize the sultan’s authority, but do not receive a nizam that they will replace with a soft ransom, but according to the valuable possibilities of their region.

Only later, the pashas of Dibra, Spic, Gjakova, the Shkodër kadi Ibraim Dagi Mustafa, three other prominent Malisori tribal leaders and 12 Christian elders – although they did not actively participate in the rebellion against the Shkodër vizier – were deported to Constantinople or executed in the fortress. The Shkodër Pashaluk, on the other hand, is divided into two parts: narrower: from Shkodër to Lezhë, and territories that, with less local competences, were annexed either directly to the Vali of Rumelia or to the pashalik of Janina, Vlorë and Delvina, who was also subordinate to Rumelia. The temporary administrator of this reduced Shkodër pashalik was Bajram Pasha; it was only in mid-December 1835, the real Vizier of Shkodër, Osman Nuri Pasha.

At the beginning of 1836 Turkish troops, in order to ensure the authority of the central administration in Albania, were deployed as follows: in Shkodër 2 battalions, Elbasan 1, Krujë 2, as the main strategic centers. 100 Hafiz Pasha, to whom Porta acknowledged gratitude for maintaining the sultan’s authority in Albania during the difficult months of the Arbanian movements, was transferred to Chitaja in Asia. The new vizier Osman Nuri Pasha began his administration of northern Albania, as conditions had been considerably altered by force to the detriment of Arbanas. Albania was then ruled by relatively well-guarded internal peace for a few years.

If the causes of the Arban uprisings during the viziership of Hafiz Pasha in 1834-1835 are summarized, it will be seen that they were the following:

(1) the presence of the Turkish army in Albania and its occasional interference in the civilian affairs of Albanian society,

(2) an attempt to introduce strings among the Arbanas,

(3) the introduction of new taxes related to the support of this army, and otherwise,

4) lack of full security and public order, which in particular hinders free movement and trade,

(5) restriction of trade by customs and monopoly by the vizier,

(6) attempts to disarm the kulukcibas of Shkodër town and bazaar,

(7) attempts to suppress the political influence of the Arban Beys,

(8) attempts to penetrate into the inner affairs of tribal life, e.g. through the replacement of individual heads, and finally

(9) violent imposition of the ransom, since the abdication proved to be unenforceable by peaceful means.

All these were the causes, some of them also the immediate causes of Albanian-Turkish conflicts and uprisings in Albania at that time.

What was the characteristic, and what were the consequences of this political and socio-economic state of Albania, and of these Albanian-Turkish mutual relations?

Rebellions and uprisings in Albania in the 1830s, so numerous in their events and so sudden in their causes, were suppressed by the Turkish central administration after a longer or shorter military intervention, leaving behind no visible traces of a broader movement with a national liberation tendency. Without a developed civil class and a developed economy, largely incorporated into tribal frameworks, into separate special geographical units and separate confessional groups, the Albanian social environment could not, at this time, bring to the surface a program of the anti-Turkish movement based on the political-political-national liberation struggle, but rather clung to the times and the historical development of conscious principles of defense and preservation of the state, rights and privileges of preserved tribal and feudal socio-economic relations.

Hence, after the fall of the strong personality of Mustafa Pasha of Shkodër, during 1832-1836, all movements were doomed to failure, with one exception that, even if they failed, they constantly weakened Turkish power and Turkish administration in Albania, without opposing it with any new form of self-government and self-administration. what would this latent repression of the Turks lead to a certain, second-strong political and social order.

The events in Albania in 1832-1836, during the viziership of Namik Ali Pasha Moralija and especially Hazif Pasha, clearly show this state of affairs. The viziership of Hafiz Pasha is a typical example, on the one hand, of how and to what extent the Turkish power in Albania weakened, and on the other, an example of the backwardness of the Albanian social environment to use this weakening of the foreign, Turkish, power, until after 1878, to use it, like the Serbs and Greeks, for the political-national purposes of complete emancipation from Turkish Empire.

Spontaneous in their origin and development, they acquired the appearance of indeterminacy and vacillation both in their goal and in their completion. Without a certain and clear new political perspective, in backward social conditions and underdeveloped economic relations, the Arbanas locals, often unorganized and without common interest among certain tribes and certain regions and certain pashas, in the 1830s took the form of a successive series of struggles that did not organized into a more permanent, consequential and, from a socio-political position, progressive anti-Turkish movement.

Not having a definite and clear perspective of the future development of Albanian-Turkish relations taken as a whole, they turned to the old and returned to the old. Anachronistic in their development and in their special contribution, and in relation to the general course of national-revolutionary development among the Balkan peoples of that time, they were therefore condemned to decline.

Mich. Gavrilović presented the ideological and psychological basis of the movement under Mustafa Pasha Shkodër, and Drag. Pavlović also pointed out the Arbanian co-dominated and unorganized, feudal and tribal way of warfare. The great physical energy expended in the fight against the Turks could not achieve results precisely because of this social and political division among the Arbanese population, in which the clan-tribal base was characteristic in the mountainous regions, and the feudal one in the Drima and Primorje plains.

Weak built branches, separated by petty personal and local interests, without an organized broader market, a broader cultural background and a broader political perspective, perspectives, at the same time confessionally and nationally divided, in a collision of understanding between public loyalty to the Turks under the assumption of reforms in the administrative order and guaranteeing the security of trade, persons and wealth, and secretly emphasized sympathies for the prosaic lithistic inclination of Catholic Austria, for which there is also some evidence – they were powerless, due to their composition, number and political orientation, to take the development of events into their own hands and to give it a certain national-liberation political and social content.

Hence, all those uprisings failed one after the other, and in Albania they prolonged the Turkish political power. Due to such objective difficulties in the political and social development of Albania in the 1830s, just ten years later, Garašins actions in connection with the program from Nachertani will also encounter considerable difficulties.

Hence, Albania, having no perspective of its own liberation and in a collision with the national expansions of the neighboring states of Montenegro, Serbia and Greece, during the 19th century, will remain the largest reservoir of the armed forces of the Turkish Empire and, in essence, the greatest support for the survival of Turkey in the Balkans.

Reference

Историјски часопис 7 (1957), Istorijski institut. Vladimir Stojančević. Link.