Written by Petrit Latifi

Saxed from an article by Albanian editors on Albanian Wikipedia. Translated by Petrit Latifi.

Conquest and rule during the Ottoman period

After two sieges and incorporation into the Ottoman state, Shkodra became the center of the sanjak of the same name and the sanjakbey was Koxha Jusuf bey, who is considered the first of the Bushatllinje clan[1], within the Elajet of Rumelia. After 1479, Andrea Locha (Loha Zade, Ali Aga) received a timar,[2] who is considered the first of the Lohja family located in Shkodra, near the castle.

It is thought that this is the oldest timar in Shkodra[1]. In 1485, there were 27 Muslim and 70 Christian homes in Shkodra, while by the end of the next century there would be 200 Muslim and 27 Christian homes, respectively[3]. During the first centuries of the Turkish occupation, the Catholics of Shkodra were allowed to live in Zues, Tej-Bunë, Bërdicë, Kuç and Rrëmaj. In Tebune there was a village or neighborhood called Chisen or Chisagno, Kazenë or Kishaj. Regarding the population of this neighborhood, Pjetër Budi also reports in his report of September 15, 1621 that:

“The peoples who are near the bridges and around Shkodra have 1000 warriors and their places are Shiroka, Rizani, etc.” [4]

In 1671, this locality, together with the entire space between Shiroka and Shkodra, had a full 2000 inhabitants, whose name, according to microtoponyms, survived in some properties such as Livadhi i Kishejve, Pusi i Kishejve; because it was abandoned after a plague epidemic in 1819 [5][6][7]. Shkodra enjoyed gradual expansion and prosperity over the following centuries, becoming the capital of the Pashalik in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.[8]

The traveler Evliya Çelebi, in his “Book of Travels”, when he visited Shkodra in 1645, received in his palaces in Bushat the ruler named Mehmet Pasha, heir to the aforementioned Yusuf Bey. In describing Varosh (the city outside the walls), he states:

“There are 1,800 Muslim houses with two floors, all built of stone, covered with slates and tiles and surrounded by vineyards and gardens. There are 15 neighborhoods, among which the most notable are: the Bajazid, Alibegaj, Hysenbegaj, Sqelës, Muftiës, Karahasej and the Gjykatores neighborhood at the end of the bazaar. Shkodra has 11 mosques, the most famous of which are the Bayazid Mosque at the head of the market, which has a very good well in front.

It is covered with tiles and has a large congregation. Then comes the Hysen Bey Mosque in Alibegaj, the Mufti Mosque in Sqelë and the Karahasej Mosque. In addition to these, there are 70 mosques. There are 7 mejtepes, but no school for reciting the Quran or Hadiths. There are 500 shops in the covered market, where all crafts are represented. The fish market on the square is well-maintained and abundant.”[9]

The aforementioned Alibegaj neighborhood has had this name since the so-called Ali beg, the son of Smajli, left a large estate as a waqf to the neighborhood mosque in 1529, which Çelebi calls Hysen beg. According to Dom Ejëll Radoja, the mosque was once the Church of Saint Lawrence; the mosque stood until shortly before independence, when many residents abandoned the neighborhood due to the risk of malaria and flooding.

Not far from this neighborhood, at the entrance to the Bazaar there was a Hamam built by the so-called Allaman beg in 1519, known as the Old Hamam. Pjetër Bogdani mentions that at the entrance to the hamam there was written in marble with Roman numerals (1470, October 5)[7]. Bushati thinks that with the Hysenbegaj neighborhood or the Mufti’s neighborhood he meant the Ajasëm neighborhood[7] – which is a Greek toponym and means “holy waters”, although undocumented.[10][11]

According to the folk song “Zani i Kasnecave”[12], in 1577 a great uprising broke out against the Turks and after a fierce and bloody battle that took place at the “Lama e Spahive” the Turkish army was badly defeated and the people of Shkodër gained the right to be governed by local rulers and for this reason the Begolls of Peja were established[5] – a fact that does not find any coincidence in the lists made by the researcher Hamdi Bushati on the history of the city’s Valins in his two-volume monograph[1].

In 1641 Frang Bardhi finds Mehmet Bey, also mentioned by Evlija Çelebi, as ruler. After a gap in time between 1683 and 1696, Sylejman Pasha of the Bushatllin family appeared on the scene, mentioned until 1704[1]. Around 1700, the castle and parish of Kazena were transferred to Tophane, near the seat of the Venetian bailiff. The first to build a house in Tophane as a vice-consul was Anton Duoda[7].

Duoda wrote in 1736 that the city had 1000 shops[13]. In 1745, Tophana was the center of the parish with 150 houses and 680 inhabitants, and the church built there was dedicated to Saint Doda. The register of Bishop Pal Kamsi mentions the following Catholic settlements: Tophana, Rëmaji, Kazena, Sh’Lavrendi, Qafa, Kishaj, Zarufa, Shiroka and Kepi i Madh[5].

In 1730, Mehmet Pasha Begolli was appointed ruler, who was killed at a place called Hamam i Ri, and after him in 1738, Hudaverdi Pasha Mahmutbegolli. In 1740, Sulejman Pasha Çausholli came to power, and since he died that same year, his place was taken by his brother Yusuf Pasha Çausholli, who in 1743 went to war in the Ottoman-Persian war.

His nephew, Muhtar Pasha, was appointed and continued until 1745. During this period, the internal strife between the Terzins and Tabaks factions in the city began, embodying the rivalry between the feudal lords Çaushollaj-Begollaj that reached its peak in 1751 and lasted until 1753.

To calm the situation of the factions of the families and some agallars, Abdullah Pasha was sent to Vlora in 1745, who took measures and burned the feudal palaces and exiled several members of the Tabaku family. The Begolls kept their headquarters in Prizren or Peja, while in Shkodër they left a deputy from the Gjylbegu family[1], Kopliku-Xhabiej or Dizdari[14]. On the side of the Çaushollaj, the families of agallars and spahis that supported them were the Gradaniks and Maxharrs.

This entire period of the first half of the 18th century was accompanied by unrest, which also dictated the position of the mytesarif in the city, which most often passed between the Begollajs, the Çaushollajs and Abdullah Pasha of Gjakova. In October 1755, the Sublime Porte appointed Omer Pasha Kavaja as mytesarif.

This pasha was mainly concerned with the expulsion of the Çaushollajs and on December 3, 1755, he forced them to flee by force. He burned and looted the palaces of Mehmet Pasha Çaushollaj, Abaz Bey and the Gradaniks (uncles of Mehmet Pasha).

Pasha of Shkodra

In 1757, the Sublime Porte officially recognized Mehmet Pasha the Elder as mytesarif, which continued until 1775. With this ruler, a period of some autonomy began, which this dynasty maintained generation after generation until its capitulation in 1831[1]. The city would enjoy or suffer influences that fluctuated according to the policies pursued by this chimney.

Mehmet Pasha had as a winning factor the reconciliation of the tailors’ and tabak’s guilds since the influences of the previous feudal lords had already faded, and a softer approach to the Catholic element of the surroundings and their approach to live near the city, giving the land in the Buna, Drin and Mat discharges to the inhabitants of the Greater Highlands as well as the land in the discharge of the Buna, Drin and Mat. In 1775, with the death of Mehmet the Elder, the Porte appointed Mehmet the Pasha of Kystendili, who was not accepted by the Shkodra nobility.

Finally, he was appointed as the mytesarif by Sultan Mahmut the Pasha of Bushatlliu – one of Mehmet the Elder’s sons. The new mytesarif expressed in action an expanding tendency for the boundaries of the pasha’s authority and an equally broad freedom towards the authority of the Porte. In June 1785 he brought Montenegro under his rule, then he defeated his rivals in Central Albania by fighting with Ahmet Kurt Pasha of Berat and reaching with his army as far as Lushnja, Elbasan and Korça; thus taking the castle of Peqin.

In 1787 the first fermanli was proclaimed, the Sublime Porte dismissed him from the post of head of the pashalik and launched a military expedition against him[15] which initially found the support of one of Bushatlli’s most loyal followers, Tahir agë Juka. Besieging the fortress of Shkodra from August to October of that year, during which time the besieged strengthened his positions and encouraged the loyalists outside to launch a two-pronged attack on the besiegers, with a frontal attack from both his scots inside the fortress and the more surprising intervention of the loyalists from the rear in the city and the province led by Tahir aga Juka, now returned after strengthening the positions of Mahmud and Haxhi Idriz aga Lojje[16].

His besiegers, except for Mehmet Pasha Çausholli who was beheaded, became friends of Mahmud and his guarantors at the Porte to pardon him[17] in 1789 with the enthronement of Sultan Selim III. In June 1788, Tahir aga was beheaded for treason and burned down the palaces in the Parrucë neighborhood. In 1792, Kara Mahmud was declared a fermanli for the third time, dismissed from the post of vizier and sentenced to death, in 1793 the next punitive campaign was sent to besiege the fortress of Shkodra and with the same scheme the besieged were released after three months.

He obtained a pardon through the intervention of the King of Spain in 1794[16]. With his death in 1796, his successor Ibrahim Pasha undermined the growing independence of the pasha[15] and pursued a more loyal policy towards the Porte, but the independent spirit, giving even more economic development to the city market, resumed with Mustafa Reshi Pasha.

In 1786, a report by Monsignor Gjergj Radovan states that Tophana and Rrëmaji have 406 Catholic houses and 2131 inhabitants[18]. With the establishment of public order and social balance, the protection of the interests of local merchants eliminated anarchy, and encouraged the production and trade of goods. The Shkodra Bazaar enjoyed a flourishing of internal and external trade, which gave the city significant importance in its relations with the province and the region.

In addition to the handicraft workshops-shops, dozens of bakeries, grain and oil mills and shajaku workshops served the needs of the urban and rural population, while the inns and caravanserais around the bazaar, cafes and taverns provided temporary accommodation for customers coming from the villages of Krajë, Malësia e Madhe, Dukagjini, Puka, Mirdita, Malësia e Gjakova and up to Peja.

With their caravans they brought to the market their agricultural and livestock products: transport animals and livestock, wool, leather, cereals, dairy products, olive oil, fruit, timber, cashews, wax; handicraft products such as ropes, woodwork, and wattle. Then they returned to their countries with food products such as coffee, salt, sugar and industrial products such as clothing, various utensils and furniture, metal tools, kerosene, weapons, jewelry, etc.[19]

Such was the prosperity that at the vizier’s meal, tanneries could be found one after another in the Tabakeve neighborhood, which took its name from the tanners’ guild[20] and left a legacy in the field of home crafts that lasted until the end of the 18th century, where about 2,000 traditional looms, where women worked according to the orders of entrepreneurs and market demands.

Agricultural crops, such as cereals, olives, tobacco, and cotton, were oriented towards the market, and the expansion of the monetary economy in the countryside influenced the development of internal trade[19].

This led to a flourishing of trade across the Adriatic, mainly with the Republic of Venice, where 130 mercantile companies were established by Shkodra merchants[21] who had established a trading company called the “Shkodra Square Committee” even before the establishment of the pasha[7].

With Venice in its final throes and with the naval strengthening of France, Holland, England, and several Italian cities such as Ancona, many consular agencies were opened in the city, such as the English, Dutch, Venetian, Ragusan, Austrian, etc. By protecting the interests of the Shkodra reshphers and the Ulcinj reis, with whom they collaborated, the Bushatlin viziers managed to control not only the transit trade of the Durrës pier, but almost the entire Ottoman coast on the Adriatic – which made Venice protest strongly at the Sublime Porte.

One of the characteristics of the Shkodra trade was the participation of large feudal estates. In addition to the Bushatlins, the estates of the Kopliks and Sokols are mentioned in the letters of the Venetian consuls. From the consulate documents we learn the names of many Shkodra merchants:

Andrea Kambësi (1741), Anton Boriçi (1741), Hasan Vorfa (1741), Andrea Pema (1741), Hasan Kastrati (1744), Ali Mehmet Shkodrani (1746), Engjell Muzhani (1747), Hasan Parruca (1749), Hasan Garuci (1767), Halil Rrjolli (1768), Ali Meta-Shkodra (1768), Ndrek Zoga (1780), Gjon Melgusha (1784), Hasan Kçira (1784), Engjell Suma (1794), Gjon Serreqi (1798), etc.

A major role in this trade was played by the navigation of the Buna, which allowed the navigation of small ships up to 90 tons. On the Buna, the river pier of Pulaj served at the mouth of the river, Shirq and Obot, in the middle of it, and that of Pazar, at the foot of the castle. This way, communication was established with Shëngjin, Ulqin, which was essential with its large shipyard, and Tivar, ideal for medium and large ships[19].

The patriarch of the pashalik built important objects for worship, education, culture, and movement, such as: the Bahçalëk Bridge, the Moraça Bridge, the Mes Bridge, the Niksic Bridge, the Lead Mosque, the Qafës Madrasa,[7] and perhaps also that of Tamara. During the time of his son, Karamahmud Pasha, the Pazar Madrasa and the Vakëf Library were built, and during the time of Ibrahim Pasha, the construction of the Bexhistën Bridge began[7].

The End of the Pashalik, the Tanzimat

With the Sherri Vaki, as it was known in the Balkans, the Janissary Chimney collapsed, causing this echo to have its impact in Shkodra where, after the departure of Karamahmud Pasha to Kruja, Mustafa Pasha dealt the strongest blow to the Bektashis. With the continuous violations of Mustafa Pasha and his departure with the reforms against the ayan system of Sultan Mahmud II, after the massacre of Manastir, it was understood that the system of ojaks who had hereditary rule would be changed with a centralized system of appointment with non-native pashaliks.

The Tanzimat Revolt

From the dissatisfaction that had been aroused by the measures taken, in 1835 Hafiz Pasha took measures to dismiss the vocal opponents and demanded from the citizens 100 people for the Shpuza castle plus the cost of the castle’s repairs. Among them was the representative of the beylers Hysen beg Bushati, of the craftsmen Hamza Kazazi and Dasho Shkreli, and of the clergy Haxhi Idriz Boksi and Ahmet efendi Kalaja; who launched the uprising against Hafiz Pasha[7].

Environment

The siege of Shkodra, the end of the war and the Conference of Ambassadors began to create a situation that was not at all favorable for the Montenegrin armies. Realizing that the situation was going against them, the Montenegrins increased their attacks and bombardments, with the idea of subduing the city and making it theirs before the discussion of the northern borders began. Against Russian will, the Conference of Ambassadors had recognized the independence of Albania, but had made frightening “corrections” of the borders in favor of Serbia, Montenegro and Greece.

Shkodra was foreseen in the Montenegrin area, but a short time later, Austria-Hungary and Italy remembered that it was the center of Albanian Catholicism. As a result, together with the help of England, they decided that the city should remain in Albania. The Tsar himself sent a telegram to Prince Nicholas of Montenegro and the King of Serbia, in which he explained the decision and the inability of Russia to oppose this decision.

Immediately after this decision, the Serbian troops withdrew from the siege of Shkodra, while Montenegro did not accept. In response, the British parliament held a discussion session on the siege of Shkodra and Foreign Minister Grey was summoned to give explanations. Grey gave an open, but also very cynical speech.

“We know that after a while our children will see all this as a great injustice. They will be surprised that lands inhabited mainly by Albanians or entirely by Albanians have been given to their neighbors. This is unjust, but they will understand that the balance of the Great Powers could not be broken for a country called Albania”.

Gray did not forget to explain that the war that Montenegro was waging in Shkoder was no longer a war of liberation, but a real war of conquest. He added that all the Great Powers are against this[22]. The capture of Shkodra can be considered to have been only a belated and failed attempt by Montenegro, as the Powers would subsequently force it (Austro-Hungarian diplomacy with Foreign Minister Berchtold and Count Mensdorf made a great contribution) to withdraw and leave Shkodra in the hands of the International Commission of Admirals. 13.6.1913 The Albanian National Flag is raised in the Shkodra Castle, the patriot Karlo Suma delivers a speech.

Raising the flag in the Shkodra Municipality

In November 1913, the National Flag is raised for the first time in the city municipality. For Austria-Hungary, there were primarily (national) racial and religious reasons for not handing Shkodra over to Montenegro. The surrender of Shkodra was considered more of a betrayal than a victory. Ismail Qemali received Esta Pasha with honors as he arrived in Vlora to take up his post.

But the surrender of Shkodra created problems for pro-Albanian diplomacy. The unanimous decision of the great powers to give Shkodra to Albania was complicated by the Montenegrin presence there. Russia again entered the game and asked the Conference of Ambassadors that Gjakova, the northeastern city that had been left to Albania, be given to Montenegro, on the condition that it give up Shkodra.

The situation between Austria-Hungary and Russia became tense again, but everything was again resolved in favor of the Slavs. One morning in early May 1913, the Austro-Hungarian Ambassador in London, Count Mensdorf, requested an urgent meeting with the British Foreign Secretary, Edward Grey. Having just gotten out of bed, Grey was forced to wait for the count dressed in his home clothes.

Before he even entered the door, the count exclaimed with euphoria: Austria-Hungary and Russia no longer have to quarrel among themselves. We accept that Gjakova should pass to Serbia or Montenegro on condition that Shkodra remain in Albania. Grey approved at that very moment and the pact became official[22].

On April 14, 1913, the Montenegrins burned the Shkodra Bazaar, after looting it, and left the country in the hands of the international army (Austrian, Italian, French, English, German).

The Liberation

The 6-month anniversary of independence rally, celebrated by the people of Shkodra in Kalà, where Father Vincenc Prennushi gave his speech.

Vice Admiral Burney entered the still burning city. On May 15, the New Municipal Council was created, consisting of 6 Catholics and 6 Muslims. All under the orders of a British man. After more than 450 years, Shkodra was free again[22].

Austria also linked these reasons to the international acts that had established for it the right of protectorate of worship over Albanian Catholics.

“Austrian feelings,” said the Austrian ambassador in London Mensdorf, “would be mortally offended if this population were to merge into a small state with which it had no racial or religious affinity.”[23] To pressure Montenegro to lift the siege, several Austro-Hungarian warships accompanied by Italian, English and French ships demonstrated in the Adriatic waters, opposite Tivat[22].

In 1913-1914 the city was administered by the great powers[24], by the International Commission with Austro-Hungarian delegates. 1915 A provisional government is established in Shkodra, but it is more anarchy. Fighting takes place between neighborhoods between nationalists and supporters of Esat Pasha Toptani. 5.6.1915 Krajl Nikola Petrovic I, Krajl of Montenegro, together with his army marches through Shkodra and enters Italy.

1915

The defeated Serbian armies march through Shkodra, where in Shtoj they shoot Mustafa Qulli and Çerçiz Topulli, the famous captain who had gone to the north of the country for the sake of the Albanian cause.

1916

The Vanguard of the Austrian army enters Shkodra. 23.1.1916 The Austro-Hungarian armies, having occupied Northern Albania, Serbia and Montenegro, arrive in Durrës.

Franz Ferdinand Street

Official visit to Shkodra by Archduke Karl Salvator of the Habsburgs.

1916-17

The “Literary Commission” is established in Shkodra. 30.10.1918 The Austro-Hungarian armies leave Shkodra and Albania. 11.1918 The Allied armies enter Shkodra. With the end of World War I, an international administration is established in Shkodra. After the Congress of Lushnja, in 1920, the city is administered by the Albanian government that emerged from this congress. 2.1920

The French army leaves Shkodra. Around 1920, the Koplik War took place, in which Shkodra participated with the districts of Malsina in the struggle for freedom that some Serbo-Montenegrin chauvinists wanted to rob them of. In 1921, the Mirdita uprising took place, led by the Gjonmarkaj family against the central government of Tirana.

In this, Shkodra also participated voluntarily to suppress it. On June 6, 1924, the uprising against Ahmet Zog broke out, and the people of Shkodra, the mountain people, and the villagers participated voluntarily.

In 1926, the Dukagjin Uprising broke out, and if it were not for the betrayal in the middle, the mountain people would have entered Shkodra, taking control, after they had reached the Middle Bridge. The hanging of the Catholic priest Dom Gjon Gazulli on March 4, 1927, made an extremely great impression on the people of Shkodra. In September 1936, the prefect of Shkodra, Javer Hurshiti, discovered the place where Ç. Topulli and M. Qulli were buried.

He found their remains, which he placed in two coffins and invited the municipality of Gjirokastra to send a delegation to participate in the ceremony of escorting their remains, which was to be held by the municipality of Shkodra. On this occasion, a delegation headed by Beso Gega left Gjirokastra. After resting for a day in Tirana, Enver Hoxha also joined the delegation.

The ceremony took place in front of the Shkodra Municipality building on September 14, 1936. The speeches given on this occasion by Father Anton Harapi and Ernest Koliqi are well known and published in the press of the time. On this occasion, Enver Hoxha also came out from the second row, and gave a speech that was never published, but was captured by photographer Kel Marubi.

During the communist regime, this photo was published by deleting the images of all the personalities who were present, at that moment, on the balcony, leaving only the image of Enver Hoxha. Enver Hoxha also lied in his memoirs that he supposedly took off his jacket, rolled up his sleeves, and worked with a pick and shovel to find the remains of the two martyrs, at a time when the Gjirokaster delegation arrived in Shkodra, everything had been prepared beforehand.

If we compare the original photo found in the Marubi Photo Library with the retouched one published in the books of the time, where Enver Hoxha is shown speaking alone on the balcony of the Shkodra Municipality, the deception made is clearly visible.[citation needed]

In the years 1924 to 1939 there was an industrial development with small factories mainly in the food and cement industries. In 1939 there were about 70 such factories. During this period of monarchy the city had a European administration, with regular institutions, and a series of progressive reforms were carried out.

In 1939 Albania was invaded by the fascist armies of Italy, on April 7, 1939, the Shkodra youth asked for weapons to escape, but they were denied: despite this, the black shirts of the fascist government awaited them from the fortress and from the banks of the turbulent Drin with rifles in their faces. Living proof that the murder of Lieutenant Bombigi at the Drini Bridge.[25]

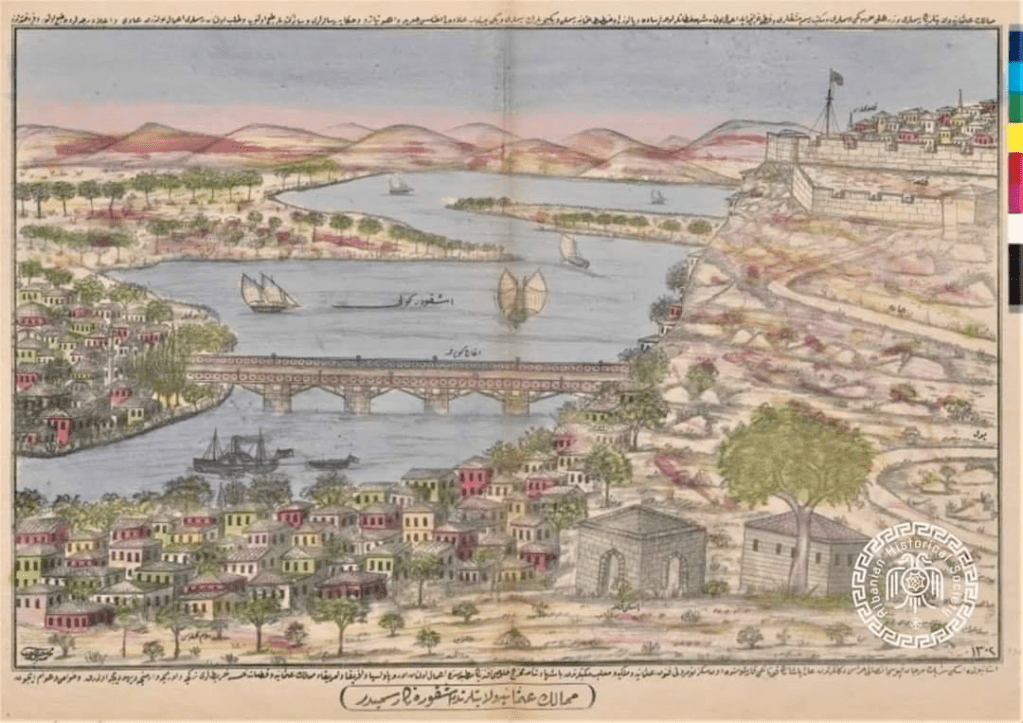

Shkoder in 1884 in an Ottoman map

References

- ^ Bushati H., Shkodra dhe motet (traditë, ngjarje, njerëz) v. II, Shkodër: “Idromeno”, 1999.

- ^ Bushati H., Shkodra dhe motet (pemë gjenealogjike familjesh shkodrane) v. III, Shkodër: “Idromeno”, 1999.

- ^ Clayer N., Is̲h̲ḳodra, Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill Online, 2012.

- ^ Zamputti I., Dokumente të shekujve XVI-XVII per historinë e Shqipërisë. Vëllimi III (1603=1621), Tirana 1989, ff. 376-389.

- ^ a b c Sheldija Gj., Kryeipeshkvia Metropolitane e Shkodrës dhe Dioqezat Sufragane Arkivuar 3 mars 2016 tek Wayback Machine, Shkodër, 1957-’58.

- ^ Armao E., Località, chiese, fiumi, monti, e toponimi varii di un’antica carta dell’Albania Settentrionale, Roma: Istituto per l’Europa Orientale, 1933. fq. 53.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bushati H., Shkodra dhe motet v. I, Shkodër: Idromeno, 1999.

- ^ Elsie R., A Biographical Dictionary of Albanian History, I.B. Tauris, London-New York: 2012, së bashku me QSA. ISBN 978-1-78076-431-3.

- ^ Dankoff R., Elsie R. (red.): Evliya Çelebi in Albania and Adjacent Regions (Kosovo, Montenegro, Ohrid) Arkivuar 3 janar 2018 tek Wayback Machine, Leiden 2000, ff. 27-57. Translated from the Ottoman Turkish by Robert Elsie and Robert Dankoff. Duke e krahasuar me përkthimin e S. Vuçiternës dhe monografinë “Shkodra dhe motet” I&II të H. Bushatit, përktheu Sait N. Saiti më 20 qershor 2017.

- ^ Kamsi W., Shkodra, kryeqyteti historik i Shqipnisë, Art & Trashëgimi, 2012.

- ^ Valentini Z., Përfundime historike të nji dokumenti, Shkodër: revista “Leka”, vj. VI, nr. VIII, fq. 260.

- ^ Ardian Vehbiu e çmon si hoax dhe osianizëm këngën, krijim i një poeti i shekullit XIX. Zef Jubanit pas gjase.

- ^ Studime historike, Volume 4, Akademia e Shkencave, Instituti i Historisë 1967, fq 62.

- ^ Vlora E., Kujtime 1885-1952, përktheu Afrim Koçi, Tiranë: IDK, 2010.

- ^ a b Duka F., Sfida shqiptare ndaj shtetit osman: Pashallëku i Shkodrës, Art & Trashëgimi, 2012.

- ^ a b Bushati H., Bushatllinjtë, Shkodër: Idromeno, 2003.

- ^ Jazexhi O., Kara Mahmud Pashë Bushati Arkivuar 19 gusht 2018 tek Wayback Machine, dielli.net.

- ^ Sarro I., Gjendja e të krishtenëve të dioqezës së Shkodrës në fundin e shekullit XVIII, Hylli i Dritës, Shkodër: Botime Françeskane, Vjeti XXXI, Nr. 1.

- ^ a b c Tafilica Z., Veprimtaria tregtare e Shkodrës (Mesi i shek. 18 – fundi i shek. 19), Art & Trashëgimi, 2012.

- ^ Ippen Th., Skutari und die nordalbanische Küstenebene Arkivuar 17 janar 2018 tek Wayback Machine, Sarajevo 1907, ff. 27-32. Përkthyer nga gjermanishtja prej R. Elsie.

- ^ Saraçi A., The Trade Relations between the Sanjak of Scutari (Shkodra) and the Republic of Venice in the First Half of the XVIIIth Century Arkivuar 19 tetor 2018 tek Wayback Machine, Anglisticum Journal (AJ) shtator 2016, V. 5, nr. 9.

- ^ a b c d Tratativat diplomatike dhe dorezimi i qytetit[lidhje e vdekur] nga Blendi Fevziu

- ^ Çështja e Shkodrës në Konferencen e Ambasadorëve 1912-1913 deri në momentin e dorëzimit Malit të Zi Arkivuar 16 tetor 2007 tek Wayback Machine, Dr. Romeo Gurakuqi

- ^ “Nga Romeo Gurakuqi”. Arkivuar nga origjinali më 8 tetor 2011. Marrë më 29 tetor 2010.

- ^ “Sheldia”. Arkivuar nga origjinali më 16 tetor 2007. Marrë më 22 qershor 2010.