Authored by Dr Qazim Namani. Translation by Petrit Latifi.

Original title: The Balkan Wars and the occupation of Albanian lands up to Durrës by the Serbian army during 1912 or “Luftërat ballkanike dhe pushtimi i trojeve shqiptare deri në Durrës nga ushtria serbe gjatë vitit 1912″.

Dr. Qazim Namani

For the spread of Albanians in the central part of Serbia during the 18th and 19th centuries, we also find written sources by Serbian authors (See Fig, 1). Knowing that in this period there was no Turkish population living in the cities of the Balkans, we can affirm that the vast majority of the inhabitants of the region were of Albanian origin. I think that Russian and Serbian politics, according to their platform, exploited the Orthodox Albanians who had now entered the phase of Slavism, since they knew the language, tradition and penetrated the Albanian leaders and feudal lords without any problem.

Unfortunately, the Albanian leaders, in the absence of a national platform and unity, did not understand in detail the tricks of Russian-Serbian politics, and through these people they held talks on the most important issues in the region.

Fig. 1. Evidence from Serbian literature, that in 1784, Kraljevo had only 11 Serbian and 89 Albanian houses.

Under the influence of Russian politics and the Serbian Orthodox Church, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Serbian nationalism developed a degree of hatred towards the Albanian people and the Ottoman occupation of the Balkan territories. As we learn from Serbian literature, we learn that until 1834, there were very few Serbian residents.

Based on the first census of houses in 1834, immediately after gaining autonomy, we note that in Belgrade, Serbian and Jewish houses were registered 769 houses or 25%, of the total number of houses in the city, but for a short period, in 1846, the number of houses for these two communities increased to 1720 or 45% of the total number (See Fig, 2).

Fig. 2. Evidence from Serbian literature for the registration of houses in Belgrade, during 1834 and 1846

It is also known from the sources of the time that during this period Jews and Albanians lived in the center of Belgrade, therefore, since the number of Serbs was very small, during the registration of houses and the population at the beginning, in order to increase the number of Serbs, Jews were also included, and later Vlachs.

Many of the Vlachs who had settled in Belgrade were from Albanian settlements such as: Janina, Elbasan, Manastir, Ohrid, Niš, and Skopje, (See Fig, 3).

Fig. 3. Evidence from Serbian literature for the movement of Vlachs to Belgrade from Albanian cities

From Serbian literature, we understand that after Serbian autonomy and until 1867, there was no policy to change the structure of the population that was concentrated during those years in Belgrade. Until this time, Belgrade had been populated by different people, speaking different languages and having different traditions, so much so that they did not even understand each other. After this year, several political actions were taken to assimilate and Serbify members of other communities, who settled them in Serbia (See Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Evidence from Serbian literature that by 1867, many communities speaking different languages and having different traditions had come to live in Belgrade.

Serbian authors, based on historical documents from the Belgrade archive and literature on the memories of old Belgrade citizens, have many names. We are mentioning that Ilija Arnautovic, who was a colonel and a prominent officer, was called that because he had come from the south, from Albanian lands. From this we understand that the first officers of the Serbian army, the majority of whom were of Albanian origin, had come to Belgrade from Albanian lands (See Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Arguments from Serbian literature that many Serbian army officers during the Eastern Crisis were of Albanian origin

In addition to the army from the southern Albanian territories, people with various professions had also gone to live in Belgrade (See Fig, 6).

Fig. 6. Evidence for many citizens of Belgrade, who had gone from the southern territories and had various professions.

From the territory of present-day Macedonia, a large number of residents of Albanian origin of the Orthodox faith had gone to Belgrade, who over time were Serbized (See Fig, 7).

Fig. 7. Evidence for the departure of citizens from the territories of present-day Macedonia to live in Belgrade.

As we will see later, these Albanians who settled in Belgrade during this period, who were Serbized, and who entered the Serbian military structures, committed the greatest crimes against the Albanian population, during the Eastern Crisis, and the most serious crimes in all the military campaigns that Serbia later carried out against the Albanian people.

In the last two decades of the 19th century, numerous youth and institutional organizations were created in Serbia that fought among themselves to seize power.

In August 1901, a group of young officers, led by Captain Dragutin Dimitrijevic Apis, founded the Chetnik organization “Black Hand”, this was a conspiratorial group organized against the dynasty of Obrenovic.

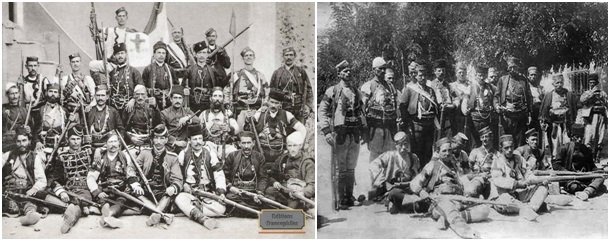

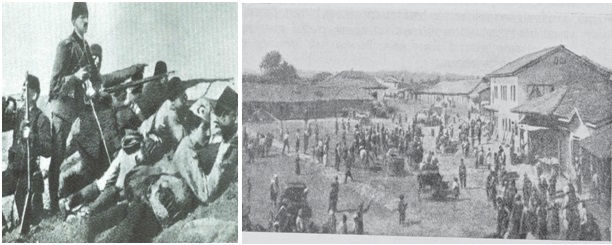

Photos, 1 and 2. Serbian Chetnik gangs that during the years 1905-1908, acted in the Albanians of today’s Macedonia

This secret organization that operated in Skopje, committed the most serious crimes against the Albanian Muslim population. Albanians were massacred in various ways by the actions of the members of this organization. Albanians were continuously pursued, killed, raped, and often by the actions of their gangs the bodies of the killed Albanians were thrown into the Vardar River.

Photo 3. Serbian Chetnik gang established in Prilep, and Photo 4. Serbian Chetnik gang established in Manastir

Vasilije Trbic, was a Serbian Chetnik, who during 1908, with his gang, massacred the Albanian inhabitants in the villages of Braillove and Desovo, in the municipality of Dellovo, which lie in the central part of Macedonia near Prilep. In Brailovo, he built a tower from the loot he had taken from Albanian families.

During the massacre, he had left only one baby alive in a cradle. The baby was a girl whom he had dressed in Serbian clothes and left in the cradle in the middle of the village. Next to the cradle, he had written the slogan that from now on only Serbian babies would grow up here. That baby was named Emine, she was a girl from the village of Desovë of the Bajraktari family.

The family went at night and took the girl, whom they raised, but due to the numerous pressures from the Slavic rulers, who wanted to forcefully marry the girls of this family to Serbian Chetniks, she was forced to move to Turkey. In addition to the numerous massacres they committed against Albanian families, these Chetniks also violated the family honor of Albanians in these parts, taking Albanian girls as wives.

Photo 5. Evidence of the massacres committed in Presevo during 1913

Albanian-Serbian cooperation and negotiations had begun since the beginning of the 19th century. Let us recall that they increased during the Albanian uprisings of the 1920s, when Mustafa Pasha Bushatliu collaborated with Miloš Obrenović, through their informants. Mahmud Pasha of Niš also collaborated with Miloš Obrenović, who in February 1831 had asked for money from Prince Miloš.

Prince Miloš had also provided assistance to Mahmud Pasha of Niš, and had sent Dimitrije Tiric there as his informant. This suited Prince Miloš, since he was very interested in having his own man in Niš. Prince Miloš chose to send Dimitrije Tiric to Niš, since he was born in Niš, was educated in the West and also knew the Ottoman language well. Tiric was sent to Niš through the consul of Belgrade with the excuse that he wanted to return and live with his family.

According to Serbian archival sources and a merchant from Aleksinci, named Gjorgje, who from April 12-24, 1844, had traveled to the city of Manastir, he had shown that the road in those areas had become unsafe, due to Albanian insurgents. According to his accounts between Veles and Skopje, at that time, about 8000 Albanian insurgents had gathered. Apparently, there had not been a merchant there, but a Serbian agent, who had the duty to provide information about the area between Niš and Manastir, so for this he had gone to Manastir, where the sultan’s army was concentrated.

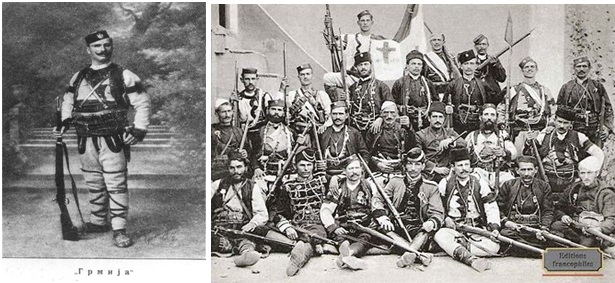

As can be seen, Miloš Obrenović had created the possibility of connections between Serbs and Orthodox Albanians in the vicinity of Kumanovo, Veles, Prilep, Manastir, Ohrid, Tetovo and Skopje. These connections were strengthened even more in later decades, and this caused the Orthodox Albanians of these areas to become Serbized at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, due to the influence of Serbian secular schools and the Orthodox Church. Based on the Serbized Orthodox Albanians in the city of Skopje, the Chetnik organization Dora e Zezë was founded in 1901.

Photo 6 and photo 7. Serbian Chetnik gang organized by Dora e Zezë, in the Albanian territories of Macedonia

War criminal Vojslav Tankosi

One of the Chetniks who committed numerous crimes against Albanians was Vojslav Tankosi? Vojislav Tankosi?, was born in Ruklada, in the Tamnava region near Valjevo, on September 20, 1880 and died on November 2, 1915. His family had previously come to live in the vicinity of Valjevo, from a Bosnian area. As can be seen from his activity before the Balkan Wars, disguised as an Albanian who operated in the Albanian territories of present-day Macedonia and Kosovo, it is implied that he had Albanian origins from Peshteri or even Tregu i Ri (Novi Pazari).

Vojislav Tankosi?, from the beginning of the formation of this organization, had become active with his actions. This group drew up a plan for the assassination of the royal couple, King Alexander and Queen Draga. On the night of June 10-11, 1903, Dragutin Dimitrijevic Apis, organized the assassination of the royal couple in the Old Palace. Tankosic, as Dragutin Dimitrijevi’s confidant? Apis, during this The action executed the two brothers of Queen Draga Mašin, during the plot to overthrow King Alexander Obrenović?, to bring to the throne King Petar Karađorđević I.

Vojislav Tankosi?, in addition to being a member of the Black Hand (Cerrna Ruka), he had also become a member of the New Bosnia, which was also accused of involvement in the assassination of Franz Ferdinand. He was arrested by the Serbian government when Gavrilo Princip assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand (June 28, 1914), but was pardoned when Austria attacked Serbia.

Photo 8 and Photo 9. The Albanian Cafe in Belgrade, where the plan to assassinate Franz Ferdinand is believed to have been made

Vojislav Tankosi?, in his youth graduated from the Gymnasium and the Military Academy, and gained the trust of Milorad Go?evac and other Chetnik leaders. Tankosi? was sent as a secret agent, undercover, to the territory of present-day Macedonia, to study the terrain, the situation and to establish contacts with the people there, for actions allegedly against P. Osmane that were planned to be carried out in the future. Also this fact that he knew the Albanian language, and as an agent easily penetrated among the Albanians, in the territories where P. Osmane ruled.

As a young man educated in a fiery Serbian national spirit, he had greatly increased his activities in Serbian youth organizations, Tankosi? at that time as a young man, tried to gain the trust of General Jovan Atanackovi?, who had begun to gather volunteers to incite uprisings in the territories where the Ottomans ruled. In the winter of 1903-04, as a member of the Serbian Chetnik Organization, Tankosi? went to Skopje, Manastir and Thessaloniki, and there he began to organize actions and groups of Chetniks in present-day Macedonia.

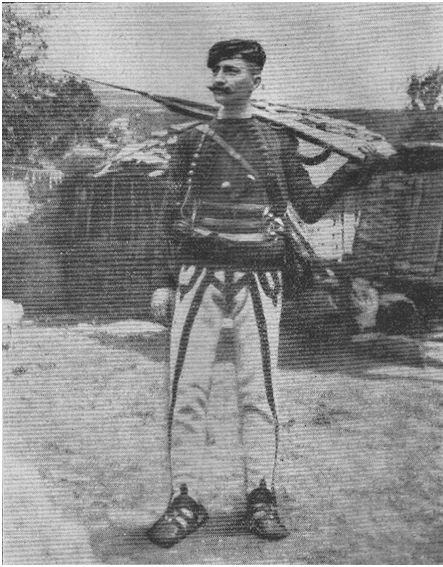

Photo 10. Vojislav Tankosi?, photographed outside Isa Boletini’s house in 1911, dressed in Albanian clothing disguised as an Albanian, during talks for cooperation against the Ottomans.

On April 16, 1905, he participated in the Battle of Pelopek near Kumanovo, under the leadership of Savatije Miloševi?.

Vojislav Tankosi?, in 1907–08 he was the Chief of Staff of the eastern Vardar area, which means that he commanded all active units from the Serbian border to the Vardar. In 1908, he led the attack on Bulgarian bands in the village of Stracin, which almost caused a Serbo-Bulgarian war. After these activities, Tankosi? returned to Belgrade in July 1908.

After the Austro-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (October 6, 1908), Tankosi? founded a Chetnik school in Prokuplje, where volunteers were trained to execute, during special operations, that were planned to take place in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

As can be seen, the negotiations of the Serbs with the Albanians, conducted for centuries, were not unknown to the Serbs even on the eve of the Balkan Wars. This is evidenced by these data about Vojislav Tankosic, who in the most cunning way took advantage during the negotiations with Isa Boletin, who was known as one of the most powerful Albanians of the time.

In the negotiations of 1911 with Isa Boletin, Vojislav Tankosic gained knowledge about the organization of the Albanians, the terrain and the military power of the Albanians. Tankosic proudly painted himself in front of the house of the Albanian military leader with whom he talked. Before the conflict with Turkey, it was very important that Serbia did not intervene in the conflict with the Albanians. Therefore, the Serbian government sent its most prominent officers to talk, so as not to involve the Albanians during the war between Serbia and Turkey.

Dragutin Dimitrijevic Apis also went to talk to Boletin, who wanted to increase the Albanian revolt against the Turkish army.

Belgrade had maintained its main connection with Isa Boletin, who was known to have a kindness towards the Serbs: The Serbian government had sent various Serbian emissaries to Isa Boletin, especially to talk with him, among whom was the notorious Colonel Dragutin Dimitrijevic “Apis”, the leader of the Serbian Chetnik movement “Black Hand”. He had come to Boletin, to influence Isa Boletin, to enter the war against Austria-Hungary.

Isa Boletin at that time was the most powerful Albanian, he was the most respected military leader who had the greatest influence on the entire Albanian people. Although Apisi returned to Belgrade, with the promise he had received from Isa Boletini to return the weapons to Austria-Hungary, no one in the Serbian government and army believed his words. This was also the reason why Tankosic decided to take matters into his own hands.

The Serbian government tried to use the Albanians against the Turks, and sent Tankosic to Kosovo, where he and Isa Boletini discussed organizing actions against the Turkish army. Tankosic during his stay in Kosovo, in June and July 1912, led the Albanians in their conflict with the Turks in the vicinity of Mitrovica.

Knowing the situation and the terrain, Tankosic himself went to Boletini, and humiliated Isa Boletini, kidnapping his two sons! Vojislav Tankosic sent Isa’s two sons to Kusumli, where they were held hostage until the war ended, with the message that their lives depended on whether their father’s word was fulfilled. The Albanians, of course, did not intervene in Serbian-Turkish conflicts, and their commander-in-chief was forced to restrain his anger, Serbian sources say.

Before the outbreak of the Balkan War, in March 1912, Tankosic was transferred to the headquarters of the border troops, in charge of well-trained volunteers for military operations, who had come from all regions with a Serbian population.

Tankosic was very strict in the selection of his volunteers, and out of 2,000 candidates, he selected only 245 volunteers for his unit. One of those who was rejected, due to his weak stature, was Gavrilo Princip, who later assassinated Franz Ferdinand.

In the First Balkan War, Tankosić commanded the Chetnik unit to attack the border at Llap (Merdare). He began operations against the Turkish army two days before the outbreak of the war, at the border point at Merdare. This border point was defended by Albanian volunteers and Albanian soldiers mobilized in the Turkish army. In this battle, the Chetniks and Albanians clashed, and this was the first battle in this war. Tankosić’s Chetniks fought for three days alone, until the regular Serbian Army joined the Chetniks in this fight. Tankosić’s role in organizing conspiracies, fighting and assassinations was decisive in the processes of the developments of the Balkan Wars, and the First World War.

His crimes were known to all armies fighting in the central Balkans.

The following is a brief overview of the activities of this notorious Chetnik, up to his assassination during the fighting with the Austro-Hungarians in 1915. During 1913, Tankosi?i, together with other members of the Black Hand, exerted pressure on the Serbian government of Nikola Pa?i?, before the Treaty of Bucharest (1913). The government tried to withdraw Tankosi?i and Apisi, but the king did not agree.

A conflict between the army and the civil authorities subsided during 1913, but later escalated in 1914, with open threats made to several ministers. It is alleged that Tankosi?i participated in the training of the Chetniks for the assassination of Franz Ferdinand. After the assassination in 1914, the Austro-Hungarian government gave an ultimatum to the Serbian government to kill Ferdinand. Tankosi? was imprisoned by the Serbian government, but he was released when Austria attacked Serbia.

After the outbreak of World War I, Tankosi? became the commander of the Volunteer Squad in Belgrade, and then the Volunteer Squad in Rudnik. At the time of the Battle of the Drin River (1914), against the Austrians, he commanded a separate band of volunteers and Chetniks on the Lim River in Eastern Bosnia, then in Loznica, Krupanj, and other battlefields. With the outbreak of World War I, Jovan Babunski formed the Chetnik unit “Sava” which then fought under the command of Major Vojislav Tankosi?. The unit continued to fight against the Austro-Hungarians in the late summer of 1914, and destroyed a railway bridge over the Sava River to prevent Austro-Hungarian forces from crossing it.

Tankosić supplied weapons to the New Bosnia organization, and had opened a school that trained Chetnik volunteers for the war against the Austrians.

The Chetnik units of Voja Tankosić and Jovan Babunski prevented the Austrians from capturing Belgrade on the first night of the war. On (6 September – 4 October 1914), he fought against the Austrians on the Drina River, and his unit was the last to withdraw from this battle. In this battle he was seriously wounded and died of his wounds two days later in Trstenik on 2 November 1915.

During the retreat of the Serbian Army in 1915, Tankosić while commanding a battalion he was wounded at Igrište near Veliki Popovi? on October 31, 1915. He died of his wounds on November 2, 1915, at the age of 35, in Trstenik.

In this battle, Albanians and Serbs fought at very close range. The Albanians who volunteered to defend the border did not have sufficient weapons. It is important to mention that two years before the Balkan Wars began, the Turkish army had begun the action to disarm the Albanians. The action to disarm the Albanians was led by the Turkish Minister of War Mahmud Shefqet Pasha, according to a telegram that he sent to the Turkish government, it is said that from Gjakova to Mitrovica, 20,000 weapons have been collected from the people so far.

The Turkish minister announced that the amount of weapons that will be collected in the prefecture of Pristina alone will exceed 15,000. During this action, taxes were increased and thousands of cattle were taken for the Turkish army. As a result of these actions by the Turkish army, the residents of the border area with Merdara gathered in the village of Dyzë and the Kulina Valley in 2010 to start the war against Shefki Pasha, but members of the advisory mission from the Turkish government were sent there to disperse the Albanian insurgents in the Kulina gorge. During the disarmament action, there was violence among the people by Turkish soldiers. Albanian deputies in the Turkish parliament even accused the Turkish army of violating the honor of Albanian women.

During 1912, the Albanians of Llapi and Galapi of the Pristina Highlands, voluntarily organized themselves to enter Pristina and to protect the border with Serbia.

Photo 11. Albanians from Llapi and Gallapi, who in 1912, were organized to enter Pristina

The Albanians of this area had also had several meetings with Isa Boletini to organize the uprising. According to the accounts inherited from the elderly people of this area, Isa Boletini was accused of not supporting and not supplying weapons. Isa Boletini at that time, due to the relations he had established with Belgrade, was hated by the inhabitants of this area.

Due to the relations that Isa Boletini had with the Serbs, people began to talk about him as a collaborator of the Serbs and a man sold to the Serbs. Sources of the time prove that Isa Boletini at that time was in a very difficult position, after the betrayal that the Serbs had made to him, with Vojislav Tankoshic. According to Malcolm, the fight that Isa Boletini waged against the Serbian Third Army in Merdare, proves that Isa Boletini had not betrayed the Albanian insurgent movement. However, in those difficult circumstances for the Albanian people, Isa’s cooperation with the Serbian Chetniks, greatly influenced the loss of trust in him and the division among the Albanians.

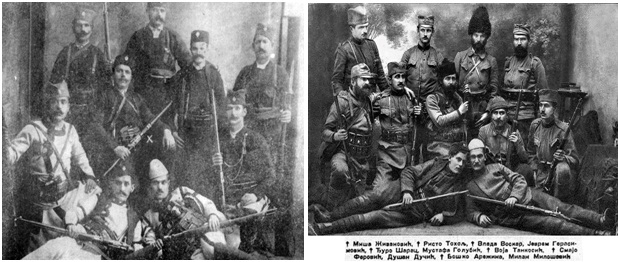

During the fighting in Merdare, several groups of Chetniks had participated, and one of the chetas was led by Vojadin Popovic.

Photo 12. Vojvoda, Vojin Popovi? (Vojin) with his group in Merdare.

Vojin Popovici was born on December 9, 1881 in Sjenica, at that time his birthplace belonged to the Vilayet of Kosovo. Immediately after his birth, the family moved to live in Kragujevac. He was educated at the military high school. On November 3, 1901, he received the rank of second lieutenant. Vojin with his band of Chetniks was among the first Chetnik groups organized in 1905, which went to the Albanian territories of present-day Macedonia. This case also proves that his family had gone to Serbia, from the Albanian territories of Sjenica, so it is possible that Vojin Popovici, like Vojislav Tanaskovici, was sent to the Albanian territories since they knew the Albanian language.

The Ottoman Empire at this time was militarily weakened, especially by the war with Italy, then by the one in Yemen and by the successive Albanian uprisings (1908-1912). Thus, several Balkan states, such as Serbia, Montenegro, Greece and Bulgaria, wanting to benefit from this situation, formed an alliance and started wars against it.

The Balkan Alliance considered the Albanian lands as “no man’s land” which could be easily conquered and assimilated. The main goal of this alliance was the fragmentation and disappearance of Albania. This Balkan alliance was mainly achieved with the mediation of the great powers and especially under the patronage of Russia and its main goal was the extinction of the Albanian nation, in order to create a new space for the implementation of pan-Slavic ideas.

On October 8, 1912, Montenegro declared war on the Ottoman Empire, while Serbia and Bulgaria declared war on October 17, and Greece on October 18, 1912. The First Balkan War dealt a fatal blow to the idea of the Albanians, since the first renascentists, to declare the true Albania independent. On the eve of the Balkan Wars, the Vilayet of Kosovo had 32,900 square km, with 1,066,891 inhabitants, of whom 63% were Albanians, 20% Macedonians, 15% Serbs and 7% others.

The Pan-Slavic alliance had as a platform the occupation of Albanian territories in order to make it impossible to realize the demands of the Albanians. In the circumstances created, the Slavic alliance found Kosovo almost unprotected by the Ottoman Empire.

The Serbs, in order to justify the war they were waging to the European powers, implemented the project drafted by Nikola Pashiqi, which, among other things, states: “Serbia wants to work in the spirit of Europe and in the realization of the desires and goals of the European powers.”

While Nikola Pašić and Petri I (First) Karađorđević were extolling the ideal of war against the Ottoman Empire, Serbian social democracy, through its organ “Radničke novine”, wrote: “The war of 1875 and 1877 was fought at the behest of Russia. In 1885, Serbia entered the war at the instigation of Russia and Austria-Hungary. So in the Balkan wars, Serbia entered the war inspired by foreign states. The Serbian Orthodox Church also blessed the Balkan war, giving support to the genocide of non-Serbian peoples. The Balkan wars of 1912-1913 were undoubtedly favorable for Russia.

At this time, there were many articles and reports from international journalists who closely observed the the massacres and burnings that the Serbian army committed in Albanian territories. Many Serbian authors also reported with pride on the war against the Ottomans. Books began to be published on the docks, traditions and the Albanian issue. Many books by Serbian authors, written at the end of the 19th century, had become a motive for murder and genocide against the defenseless Albanian population.

After the Balkan Wars, several books were also published in which they denied Albanian history, tradition and culture. In these publications, Albanians were presented as uncultured and organized into tribes that fought among themselves.

Dimitrije Tucovic in his book, regarding some writings by some Serbian authors, writes that: “When we talk about Albanians, to prove that this people has no meaning for life and culture, they present it not as a matter of the historical phase in which it is and through which all other peoples have passed, but as a matter of a weak race that is not capable of cultural development. Tucovic emphasizes that, when it comes to blood feuds, for which reason Vladan Djordjevic called Albanians “people with tails”, as if no Albanian would have the right to remind them that until recently, Dalmatinja (a woman from Dalmatia) kept her husband’s bloody clothes, to show her son that she had made him lie in her lap to get the blood”.

The hatred of the Slavic peoples for the Albanian population had its origins in the formation of the group of Pan-Slavic movements in Western Europe at the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century. This movement also drafted Pan-Slavic projects for the Balkans. One of the young Serbs who had established connections with the young Polish, Russian, Slovak, Austrian and North German was Dragiše T. Mijuškević who in 1829 wrote about Albania and the Albanians with hatred. He described the Albanians as savage Muslims and prone to plunder.

Fig. Evidence from the writings of Dragiše T. Mijuškević, written in 1829, and published in a book in 1889, in Belgrade.

Dragisha in his book “Putovanje po Serbiji”, written in 1829, even when describing the structure of the population of Belgrade at that time, still expresses his hatred only for Albanians.

Fig. data on the structure of the population in Belgrade, during 1829, where the hatred for Albanians by the author of the book Dragisha T, Mijushkovic can be seen.

From the hatred that Dragisha expressed towards Albanians, as is evident in his writings, he had also had conflicts with Albanians during that time.

Fig. Description of Dragisha’s conflict with an Albanian in Belgrade in the presence of an Austrian officer

Such publications published at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, among Serbian nationalist groups, had increased the great hatred towards the Albanian people.

The Balkan Wars proved that the Albanians were completely unprotected, and not treated as human beings even by the international factor. The Albanians were now the only people left in Europe, without education in the national language, with very poor household economies, a people divided by religion and regions, a people exploited for their own interests by the 500-year-old conqueror, who in the end disarmed, raped and abandoned them, leaving them at the mercy of their barbarian neighbors.

Memoirs of Raif Berisha and Xhemajl Beg Prishtina

As can be seen from these sources, the Albanian population was very unprepared to defend the border from the attacks of the Balkan armies. Based on the memoirs of Raif Berisha, born in the village of Sicevo, municipality of Prishtina, it is said that Xhemajl Beg Prishtina, in 1912, fought in Merdare against the Serbian army.

The fight was fought hand to hand, it is said that there were bayonet attacks on both sides. After this battle, Xhemajl Beg passed through the Albanian areas of Macedonia in Albania. In World War II, he returned to Pristina. After the communist victory, he took refuge in Hasan Berisha’s house in the village of Sicevo, Pristina.

For a long time, they kept him sheltered in an old woman’s room. Then he surrendered and was sent to the Niš prison. Since he was very old, he was released to remain under house arrest. He died in Pristina and the government of the time ordered that Xhemajl Begu be buried at the beginning of the Pristina cemetery. He was buried at the beginning of the road that separates the cemeteries, on the left side. His burial took place in the evening after it had become dark, somewhere around nine o’clock in the evening. Only 4 family members were allowed to attend his burial. I visited the burial site in 2005, with the late Raifin, but we were unable to identify his grave.

During the Italian occupation, between 1941 and 1944, the Prefecture of Prishtina was headed by Hysen Prishtina. Hysen Prishtina was the son of the Prishtina nobleman, Xhemajl Beg Prishtina. Hysen Prishtina’s descendants created successful businesses with great sacrifice. They today enjoy great authority in Turkey and Canada.

A large number of the Albanian population, now on the brink of war, and Balkans lived in the villages around Merdare and were originally from the Sandzak of Niš. Let us recall that only three decades ago these Albanian families had experienced expulsion, murder and violence by the Serbian army. The Albanian population of the border region, recognizing the Serbian army for the crimes it had committed against them, did not fight in Merdare to defend the Ottoman border, but to protect their families and Albanian territories.

The Turkish army had left the Albanians at the front without supporting them. In Merdare, the border was defended by about 3,000 Albanian volunteers without superiors and regular Turkish soldiers

The Serbian army and Tankosic’s Chetniks, during this battle, broke the Albanian army, and these were the first Serbian soldiers to enter Pristina, and other areas of Kosovo. About the fighting that Tankosic waged in this battle? was decorated with the Order of the Star of Karaçor?e Petroviqi, with swords and was awarded the military rank of major.

This is also confirmed by Serbian authors who have written that the withdrawal of Turkish and Albanian forces from Merdarje and the breaking of the resistance of the Albanians in the village of Teneqdoll near Pristina, which were the most important positions, enabled the Serbian army to expand into the Kosovo Plain and march towards Albania.

Serbian sources say that on October 22, 1912, at around 4 pm, the last parts of the Turkish forces defending the entrances to Pristina withdrew. On October 22, 1912, the Turkish army units withdrew towards Ferizaj, while the Serbian Third Army, without any major resistance, occupied Pristina.

According to Serbian sources, 1,507 Serbian soldiers and officers were killed in these battles. Malcolm says that the Third Serbian Army occupied Pristina on October 22, 1912, after having lost 1,448 killed and wounded in the fighting with the Albanians.

The third regiment of the Serbian army, which included the Medvedja district, was commanded by three commanders, who operated on the northern side of Mount Lisica in Prapashtica, and this border line closest to Pristina was also called the “Fat Gut”.

At this border point, Živko Gvozdi?, a Chetnik of Albanian origin from the city of Vushtrri, also operated with his Chetnik unit. While Sava Petrovic Germija, born in Pristina, was sent with his Chetnik group to operate in Sfircë, apparently the reason for sending him to Sfircë was because if he operated in Merdare or Prapashtica he would be identified by the Albanian population.

Photo 13. Sava Petrovic Germija, in Chetnik formations between 1906-1908, and Photo 14. Živko Gvozdi?, (seated in the first row from the left)

Photo 15. Serbian Chetnik Stefan Nedići with his group and Photo 16. Vojslav Tankosići, with his group of Chetniks in Merdare, during 1912

The Serbian government had placed the largest army forces in the villages of Medvedja. According to the Serbian military plan, it was intended to enter Pristina through Prapaštica. However, the attacks of the Chetnik unit of Vojslav Tanasković, which preceded the attacks of the regular Serbian army, caused these units from Merdare to enter Pristina first.

Prapashtica and Sfirca

After the border was broken in Merdare, the Albanian territories were attacked from all Serbian positions along the border. Albanians were attacked from all sides, killed, and entire villages were burned. The regular army from Medvedja attacked Prapashtica and Sfirca. In both of these positions, the Albanians did not have the support of the Turkish army. The Albanians, although they did not have proper weapons, fought fierce battles with the Serbian army on a voluntary basis. In Prapashtica, the entire village was burned, part of the population took refuge in the mountains, while the rest entered Pristina before the Serbian army entered from this side.

According to the accounts of my grandfather and grandmother, who had been carried by their ancestors, including members of our family before the Serbian army, they had entered Pristina with great difficulty. Our family, having a family connection with the Orana family and Salih Gogle, had taken refuge with their families, somewhere around the Velusha River in Pristina.

During that time in Pristina, all the men who were caught on the road by the Serbian army were imprisoned or killed. In one case, the Serbian army was chasing a family member of ours, who was quickly crossing the wall of a yard. His 13-year-old son Lahu, when he heard his father’s voice, opened the yard door to see what was happening in the street.

The Serbian soldiers caught Lahu and took him away. Lahu’s mother, Mihane Vrapca, burst into tears in the yard without having the chance to save her only son. The Serbian army, bayonets in hand, dragged Lahu up the road towards the village of Matičan. As the road went downhill, Lahu’s mother, Mihanja, also saw this painful scene. As for Lahu’s fate, no one knew how to tell. As the grandmother said, Mihanja had cried all her life, and was blinded by tears for her son, who had the first by dragging him in front of the bayonets of Serbian soldiers. Every person who came to the family, Mihanja had with him: Do you know anything about the fate of my Lahu.

Photos 17 and 18. Albanians imprisoned in Pristina, during the years 1912/13

After the action of disarming the Albanian population in Kosovo, by the Minister of War in the Turkish government who himself led this military operation, the Albanian population in the border zone with Serbia did not feel safe. The inhabitants of the border zone had no support, the only opportunity to be supplied with weapons was the illegal purchase of weapons from Serbian merchants.

Some Albanian merchants began to buy weapons from Serbian merchants, of course the Serbian merchants were closely connected to the Serbian army. In these circumstances, having no other option, Ibrahim Fana, Ibrahim Govori from Prapashtica, and an Albanian from the village of Hajobilë, both of these villages on the border with Serbia, buy 2000 rifles from Serbian merchants.

Immediately after the Serbian army entered these villages, all three of these Albanians are arrested, and they are asked to register the weapons as they had bought them. Since these weapons had been distributed to the Albanian volunteers who were defending the border, all three are killed and their bodies are thrown into the well of the village of Surkish near Podujevo.

Albanians killed at the town of Aleksinac

After the Serbian army entered Prapashtica, they killed over 100 Albanians and burned the entire village, in the villages of this border strip from Merdara to Prapashtica they gathered 1800 Albanian boys and men. The arrested were divided into two groups. In the first group of about 1000, the Serbian army sends them to the town of Aleksinci, and all of them are shot there at once.

Among those shot, only Imer Fana from Prapashtica remains seriously wounded, who, already seriously wounded, arrives in a few days at an Albanian family in the village of Sfircë. In Sfircë he had told about his friends who had been shot, but from his serious wounds he had died there without having the opportunity to see his birthplace with his own eyes once again.

Bulgarian encounter with the Serbian army saved 800 Albanians

The other group of about 800 Albanians, being sent to be shot in Serbia, the Serbian army encounters Bulgarian soldiers, so the Albanians, after ending up in the hands of the Bulgarians, are released, and return alive to their families. For this case, I have not found any written sources, but I have noted these events from the accounts of elderly people from this area, especially from my grandfather who was born in 1909.

These accounts probably do not have the place to be included in such a serious topic as the battle of Merdare, but in the absence of written sources and the concealment of the crimes committed by the Serbian army against the Albanians, I think that any information of this nature would be good to note, in order to complete the gap we have about our past.

That the number of Albanians killed was very large, during the military expeditions of the Serbian army, carried out against the unprotected Albanian population, is also evidenced by the sources of the time, when the Daily Telegraph reported about these events that during the entry of the Serbian army into Pristina, 5000 Albanians were killed, but also reported about another 5000 Albanians killed from the border belt to Pristina. Likewise, horrifying reports are also shown about other Albanian regions.

The New York Times also wrote about these massacres by the Serbian army on December 31, 1912. Then we also have quite important sources from correspondents from Western countries who reported the events of that time from the field.

The war diary of Kosta Novakovic, an officer in the Serbian army, a participant in the Merdar war, published in the Belgrade electronic newspaper “E-novine”, testifies to the terrible atrocities of the irregular Chetnik troops and the Serbian army. He judges the behavior of the Chetniks and the Serbian army towards the Albanians, evaluating it as a shame for Serbia and the Serbian army.

While Isa Boletini returns to Mitrovica and later to Albania, Idriz Seferi faces the Serbs again on his way back to the outskirts of Ferizaj.

During the Balkan wars, many Albanians were killed and expelled, many houses were burned, property was confiscated, art values were destroyed and the process of forced assimilation began with the blessing of the Serbian Orthodox Church. The assimilation of the Albanian population during the 19th century, and after the Balkan wars, is evidenced by documents preserved in the historical archive of the city of Belgrade. In literature and in the memoirs of In the old citizens’ registers there were many names of citizens that indicated their former non-Slavic affiliation. One of them was Arnautović Ilija, with the rank of officer, who bore this surname because he had come to Belgrade from the south, namely from the Albanian territories.

Kosta Peçanac and Azem Bejta

It is an interesting fact that in the Merdar war Kosta Peçanac also participated, also a Serb of Albanian origin from the Deçan area, who later collaborated a lot with Albanians, including Azem Bejta, and during the Second World War shared power with Xhafer Deva, in the German-controlled territory in northern Kosovo.

Russia supported Serbia with officers, volunteers, military equipment and goods. Hundreds of Russian wagons supplied the Slavic soldiers on the front line, on one occasion a Danish journalist writes that together with the Serbs in the city of Skopje they had counted 150 Russian wagons. Several thousand Slavs from the north, the Czech Republic and Slovenia volunteered to fight alongside the Serbs.

The first Serbian army, consisting of 126,000 soldiers, attacked from Vrija in the direction of Preševo and Kumanovo. The largest battle was that of Kumanovo on October 22-24. they threw. The Ottoman army on this front had mobilized 50,000 fighters. Among them were several thousand Albanian soldiers. On October 24, the Ottoman army was finally defeated at Kumanovo.

The Serbs viewed the Albanians as harmful people who should be exterminated. The Serbian army in the vicinity of Vraj, Kumanovo, Pristina and other cities killed a large number of innocent Albanians. In the city of Kumanovo, it was reported that 3,000 Albanians were killed in the villages between Kumanovo and Skopje. The Albanian villages were surrounded and then set on fire. The inhabitants who came out of their homes were shot to death like rats. This manhunt was shown with joy by the Serbian army.

In this battle, to follow the situation closely on the front line, the king of Serbia Petar Karađorđević had also come.

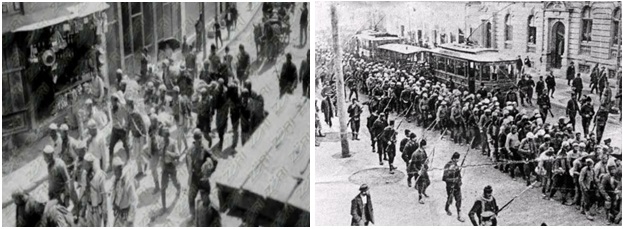

Photos 19 and 20. The occupation of Kumanovo by Serbian forces on 22-24 October 1912.

Two days later, on 26 October, the forces of the First Serbian Army occupied Skopje without a fight.

Photo 21. Albanians arrested by the Turkish army in 1912. Photo 22. Albanians arrested in 1912 by the Serbs in the city of Skopje and who were sent to Belgrade

Petar Karađorđević reported to foreign journalists that most of those killed and arrested in Vraj and other cities were Albanians. In Vraj, Prince Alexis Karađorđević, who was the son of the uncle of King Petar Karađorđević, stood next to the foreign journalists. Petar Karađorđević declared to foreign journalists that this war would bring cultural progress to the Balkans.

In the city of Vraj, the victories of the Serbian army in the battles of the front were celebrated. After the fall of Kumanovo and Skopje, celebrations were organized with songs and dances. In addition to songs and dances, the Serbian, Greek, Montenegrin, French and Russian national anthems were also sung. The dance became more and more intense, while in the streets of Skopje they celebrated with music and cheers: Long live King Petar Karadjordjevic! Long live the Balkan Union! Death to the Ottoman Parasites! To celebrate in the city of Skopje with King Petar Karadjordjevic, Prince Alexander, Prince Georg Karadjordjevic and Nikola Pashiqi, whose family origins were from a village in the Tetovo district, had also come, so all of them were of Albanian-Vlach origin.

Photo 23. The transport of Albanians from Skopje to Belgrade in Russian wagons. As we mentioned, 150 Russian wagons had come to Skopje to supply it with weapons and food

The violence of Serbian soldiers continued throughout 1913. During this year, Albanians experienced the most severe pain in the city of Pristina. This violence is also evidenced by many photographs of the time.

Photos 24 and 25. Serbian soldiers torturing Albanians in Pristina during 1913

After Kosovo remained under Serbian occupation after the First Balkan War, colonization with Serbian population began, the forced expulsion of Albanians and other non-Serbian communities, the forced Christianization of Muslims, and the confiscation of their property.

Photos 26 and 27. Serbian soldiers in Pristina in 1913

Serbian and Montenegrin legislation on colonization did not come out immediately after the annexation of Kosovo and other Albanian lands, but was delayed for several months. At first, some legal provisions were issued on the agrarian issue, which prepared the ground. The plunder of the land of the Albanian peasantry in Kosovo began as early as the last months of 1912, with the arrival of the first settlers.

In 1913, the number of arriving settlers began to increase, and along with their increase, violence against Albanians to move from their lands also increased. At the beginning of 1914, Serbia and Montenegro, with decree-laws for the regulation of the newly liberated regions, made the colonization law official. On February 20, 1914, Serbia, by means of the decree-law, officially engaged in the organized colonization of Albanian territories.

The displacement and Christianization of the Albanian population of the Muslim faith began throughout the terror of Kosovo. Regarding the difficult situation that had arisen, Monsignor Lazër Mjeda on January 9, 1913, sent a letter to the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Austria-Hungary, informing him of the Serbian violence against the Albanian civilian population. Mjeda also sent several other reports to Rome and other Western countries.

During the Balkan Wars, the Serbian army committed many murders of innocent people. This was witnessed by international journalists who closely observed these events. In the book Leo Freundlich writes that when the village of Shashare near Leshnica fell into the hands of the Serbs, they took all the men of the village and tied them up, then they began looting the houses and raping the girls and women in the most disgusting way.

In 1913 in Janjevo, the Serbian army put pressure on the Catholic church of Janjevo with the aim of forcing the believers to renounce their religion. In this bishopric, which numbered about 800 Catholics, the so-called “Laraman”, pressure was exerted on these residents to either declare themselves Muslim or Orthodox, but not Catholic.

At the beginning of 1913, the “Serbian Idea” society was formed in the city of Peja, whose goal was the Christianization of Muslims. By March 21, 1913, according to official documents, 5,000 Muslims had been converted in the city of Peja. In Peja, the campaign for violent Christianization was led by the police commander, Sava Lazarević, and captain Tomo Jaksimović.

Sava shot 17 Muslims in the village of Novo Selo, and he also began shooting in other villages in order to intimidate the villagers into handing over their weapons and converting as many as possible.

The process of Serbization is related to the fact that many Catholic Albanians were imprisoned and experienced unprecedented violence in order to become Orthodox during the years 1912-13. Below we present the facts that prove this, which Zef Mark Harapi, as a survivor of the events of 1912-13, wrote. Here is how he describes the situation of the Catholic Albanian population in the vicinity of Peja:

“As the night wore on, they tied one arm to a fence and with a stick they tied their turbans and armor and between their elbows they filled a can of water from a stone and poured it over their heads and the water poured down their bodies. On that day, many of the kshten were tied with ropes around their necks and thrown into the water with all their clothes and dragged along by the ropes and thrown onto the shore, this is how they were often washed. Many of them lost their souls to the cold water. They told the kshten to go and show them their hidden weapons.”

Zef Mark Harapi in his memoirs as a survivor of this violence reports: The complaints of the monks of Novoselë, Kruševo, Papić, Përlep and other villages were increasing for days and even more before Father Luigj Palić, who, not afraid of those bishops from Gllogjan, the place where the friar and parish were staying, tried to contact the captain of this village in Gjurakoc and told him: “Your Majesty, the monks of the Peja district are only doing bad things and are only trying to slander some of the people.”

The prisons of Peja are mentioned to have been filled with innocent people during the years 1912-1913, while Father Sava would go to the prison door and say to them: “Whoever goes to prison will be punished, the others will be executed.”

At the end of March 1913, Archbishop Mjeda complained that more than 1,200 of his followers had been forcibly converted to Orthodoxy. In May 1913, the commander of the Pristina area boasted to Belgrade that 195 Muslim Albanians had been converted in Pristina and that strong pressure was being exerted on the Catholics of Janjevo to convert to Orthodoxy.

In early 1913, a census was taken, and not a single Albanian was registered in Pristina. In 1915, a Russian journalist reported that half the population was Albanian. In 1916, according to the Bulgarian census, 11,486 Albanians were registered in Pristina.

In such circumstances, the Albanian Catholic and Orthodox population, which had endured violence during the rule of the Ottoman Empire, was forced by Serbian violence to accept assimilation on a large scale.

The Serbian government of Pašić in the international arena used the Muslimism of the Albanians as an argument, so as it has been written in many sources that the claims to the Albanian lands were related to the Serbian churches, monasteries and schools that the Ottoman Empire within its territory, in the Albanian lands, allowed Serbia to build after the second half of the 19th century. In addition, Serbia relied on international support and was supported by Russia with the force of arms.

The consequences of the Balkan wars were very great, the Albanians lost a lot, a large number of the population was killed and moved to Turkey and other countries. All branches of the economy were destroyed, the Christian Albanian population (raja) was finally assimilated so that the number of the population in the cities and villages was significantly reduced.

The third Serbian army that at the end of 1912 invaded Albania planned to go to the Adriatic Sea, to complete its strategic platform designed according to Pan-Slavic projects. The Serbian army for the invasion of present-day Albania was commanded by General Bozidar Jankovic.

The Serbian army, however, as soon as it crossed the border of present-day Kosovo and entered the Luma area, encountered resistance from Albanians. Based on contemporary sources and the international press, the Serbian army committed mass murders against the civilian population in that area. Reports from the time testify to the murder of many children, elderly people, women and the burning of 27 villages in the Luma area.

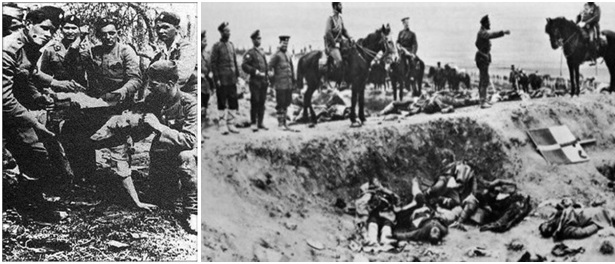

Photos 28 and 29. Massacres of the Serbian army against Albanians during the Balkan Wars in Luma

The Serbian soldiers remained in Luma, and did not retreat, the Albanians in September 1913 rose in rebellion, but the Serbian army used this opportunity to once again take revenge by committing cruel crimes against the population of Luma.

According to the writings of Dimitrije Tucoviq, the Serbian army killed hundreds of residents and burned several villages in Luma.

Photos 30 and 31. Serbian soldiers in Luma

For all these crimes committed by the Serbian army against the Albanian people, Serbia has never been indicted in an international court, but on the contrary, the crimes committed have been hidden from the Albanian citizens and the international public. Even the Albanians honored only the Serbian soldiers!

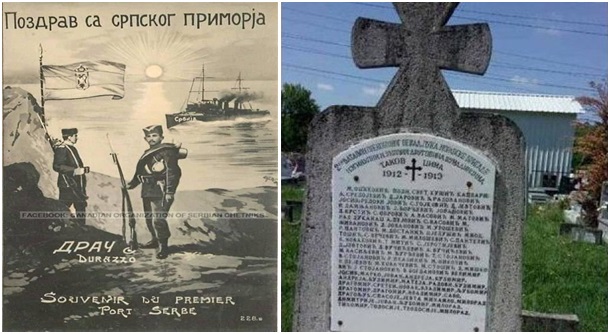

Photo 32. Serbian soldiers in Durrës and photo 33. Serbian army memorial in Tirana

Surprisingly, due to the lack of recognition of the crimes and terror committed by the Serbian army against the Albanian people during the Balkan wars, in the Sharra cemetery in Tirana, in 1939 a memorial was erected dedicated to 522 Serbian soldiers who died during the years 1912-1913 in Albania! It is truly absurd that a memorial for 522 Serbian soldiers is erected in Tirana without any memorial being erected for the tens of thousands of Albanians killed and hundreds of thousands of others displaced by the Serbian army during these wars!

The Serbian administration, after committing all these crimes and colonizing Kosovo, in addition to changing the population structure, where it brought settlers to Albanian lands, also changed the toponyms of settlements. The Serbian administration named Hani i Elezit, on the present-day border with Macedonia, after General Bozidar Jankovic, christening it General Jankovic, while the village colonized by Serbs near Ferizaj was named after the Serbian Chetnik Vojislav Tankosiq, who committed the most serious crimes against the Albanian population. Similar names were given to all Albanian territories occupied by the Serbs.

I believe this happened due to the lack of an Albanian national platform to eliminate differences in mind and pain for our population, which preserves the traditional Albanian language, traditions and culture despite minor differences in all areas of the Illyrian Peninsula.

All these testimonies that were offered in this paper are undeniable facts that Serbian soldiers during this bloody journey through Albanian territories killed and massacred thousands of innocent Albanians, and reduced hundreds of Albanian settlements in Kosovo and Albania to ashes.

Conclusion

The Albanians during the last four centuries belonged to an oppressed and discriminated people, therefore several extermination projects were drafted against our people. Considering this fact, it must be admitted that the Albanians for four centuries in a row had entered into a continuous process of murders, migration and assimilation at a much greater pace than in previous centuries.

When it is known that this grave situation of the Albanians can be argued with historical facts, therefore for the internal and external opinion the logical question is added, But who benefited from other peoples to assimilate into Albanian, when it is known that the Albanians did not enjoy any elementary national rights, and did not have any power of the time to protect them.

With the strengthening of the Albanian feudal lords from the beginning of the 18th century until their extinction in the 19th century, they survived the time by fleeing from one enemy, to enter the bosom of another enemy, and by remaining poor, persecuted and subjugated at the mercy of their enemy (the Albanian Pashals). The Albanian pashaliks that were created, to maintain their positions and by remaining servile to the sultan, benefited depending on the services they rendered to Istanbul.

The Albanian pashaliks were rewarded with posts and fiefdoms. In these fiefdoms, to fulfill the interests of the pasha and the sultan, the poor Albanian people worked. The Albanian pashaliks to maintain the positions granted by the sultan, and who were not satisfied with the collection of taxes and tortures exercised against their own people, and for these low behaviors of theirs, towards their own being, even Europe, which at that time had entered the phase of cultural and technological development, did not cry its head hard.

The Albanian national renaissance began in a very difficult phase for our people. Thanks to the general cultural movements that were revived after the French bourgeois revolution, our diaspora, which had migrated to Italy four centuries ago from its ethnic lands, revived the hope of education for our people, increased national awareness, for language, identity and antiquity, but all this effort and movement of the Albanian intelligentsia was unable to prevent the realization of Pan-Slavic projects and Turkophile assimilation programs against the poor Albanian population.

During the 19th century, the poor Albanian population, survived in its ethnic lands, despite the projects that this people was continuously killed, and assimilated according to the Slavic platform drawn up in Western countries and the programs of the Ottoman Empire for internal reforms that it had begun. The reforms begun in the Ottoman Empire severely violated the elementary cultural and economic rights of our people.

So as can be seen, the Albanian people throughout the 19th century and until the Balkan Wars were subjected to severe pressure from the two greatest military powers, Russia and Turkey, which at that time had extended their influence to the Illyrian Peninsula.

The Ottoman Empire had increased the pressures for the Islamization of the Albanians since the 16th century, by acquiring additional interests in the cities, and by the spread of Bektashism. Through these measures, the Ottoman Empire aimed to create great divisions among the Albanian people, in order to prevent cultural unity and a nationwide uprising.

From the bitter historical experience, in order to survive the times, the Albanian people must create a national platform, relying on genuine pro-Western cultural values.

It is known that the various invaders have left serious wounds, leaving us behind other peoples of the region, but we must move forward with courage to unify our national values, preserving traditional values to prove that we deserve a dignified human treatment like other European peoples.

References