Petrit Latifi

Turko-Albanoi (Τουρκαλβανοί, Tourk-alvanoi) in a broader sense is an ethnographic, religious and derogatory designation used by the Greeks for both the Albanian and Turkish political and military elites of the Ottoman administration in the Balkans, since 1715.

This identification of Albanian Muslims with Ottomans and/or Turks occurred due to the administrative system of the Millet of the Ottoman Empire; the classification of peoples according to religion.

Since the mid-19th century, the term Turk and onwards, as well as the subsequent designation Turco-Albanian, has been used as a derogatory approach to Albanian Muslim individuals and communities.

“The Albanians have expressed a mockery and disdain for the terms “Turk” and “Turkish-Albanian”, …the Turko-Albanians and those who have the same religion as the Turks, are the most warlike and political of the Muslims and do not agree on everything.

– [Gazēs, Geōrgios: Biographia tōn hērōōn Marku Mpotsarē kai Karaïskakē, Aigine 1828)]

The war against the Albanians was carried out through division, identifying the Turkalvans against the Suliotes.

“In this battle, the Turkalvans were not allies. It took place in the year one thousand eight hundred and twenty-one, on the eighteenth of April. After this battle they all returned to Sulio, to consider to which places it was necessary to send more troops, because there were some disagreements and divisions among them, as follows; who authorized the campaign to be carried out east of Soul, that is, in Dervizana, Tyskesi and Lelo, and for this reason to try to break the siege of Ali Pasha, according to their promise.

But in order that their words might have more conviction, they secretly assured many that the king was all of one mind and in agreement with the movements of the Greeks and that if the Russians came to him, the re-introduction of the summer, I had it in my ears, would become a disaster. progress and Suliotai, who saved him from danger, will enjoy more wealth and honors than all the others”

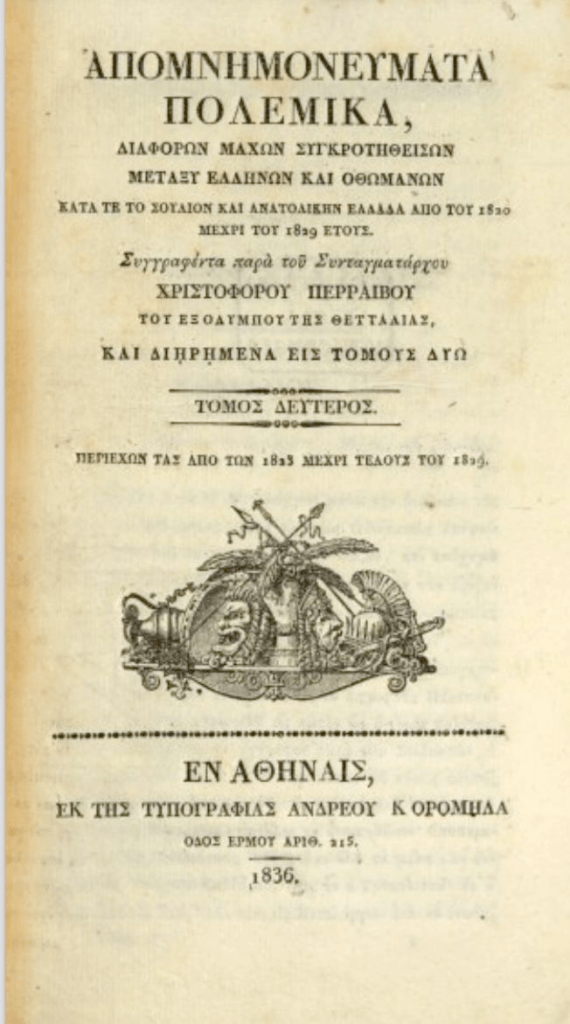

– [Perraibos, Christophoros: Apomnēmoneumata polemika diaphorōn machōn syncrotē theisōn metaxy Hellēnōn kai Othōmanōn 1820 – 1829. 1, Periechōn tas apo tōn 1820 mechri telus tu 1822]

Consequently, in the early 1880s the Greek press openly incited anti-Albanian hatred, linking the Albanian irredentists with Turkish anti-Greek propaganda and baptizing them Vlachs and ‘Turkish agreements’

– (Aión. 10 and 14 July 1880;Tzanelli, Rodanthi (2008). Nation-building and identity in Europe: The dialogics of reciprocity. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 62.

“The so-called Tourkalvanoi, a compound term literally translated as ‘Turkalbans’ and used to refer to the Turkish and Albanian Muslim elites and military units that represented Ottoman dominance in the Balkans.” – Umut Özkırımlı & Spyros A. Sofos (2008). Tormented by history: nationalism in Greece and Turkey.Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-70052-8, p. 50: “https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=eR-7aHdTIhIC&pg=PA50”

In the 20th century, anti-Albanian policies towards “non-Slavic Albanian Muslims (and Catholics) evolved into a bureaucratic category particularly vulnerable to the periodic state-directed expulsion campaigns – during the 1920s, 1935–8, 1953–67, and then again in the 1990s – that swept through the region. Constantly accused of being “foreign” and “fifth column” threats to national security, the labeling of entire regions of Kosovo, Novi Pazar, Montenegro, and Macedonia as inhabited by “Muslim Albanians” often implied the organized expulsion of those communities.

To justify such measures to the casual foreign traveler witnessing the violent process, or to delegations sent by the newly formed League of Nations at the request of Albania (a member state), the Serbian/Yugoslav state often brought in historians, demographers, and anthropologists. In an exercise often repeated throughout the post-Ottoman Balkans, operatives of the “ethnic cleansing” campaigns revived the “professional knowledge” of racial sciences first developed in the United States at the turn of the century.

In the 1920s, for example, state authorities eager to continue a process of expulsion begun in 1912—briefly interrupted by World War I—sent an army of European-trained ethnographers to “Southern Serbia” to identify those communities least likely to accept Serbian rule. These ethnographers and human geographers adopted many of the same racist epistemologies identified in other Euro-American contexts to identify and catalog the “subhuman” characteristics of the hybrid “Turks”

– [Blumi, Isa (2013). Ottoman refugees, 1878-1939: migration in a post-imperial world. A&C Black. pp. 149–150.]

On the other hand, this pathological approach to the created identity of Hellenes versus Albanians is explained by “The ‘eternal’ existence of The Other (and the relation of the Self to this Other) is provided by the name used to designate him or her. Greeks often refer to various states and groups as ‘Turks’—such as the Seljuks, the Ottomans, and even the Albanians (Turkalvanoi)”.

– [Millas, Iraklis (2006) “Tourkocracy: The History and Image of the Turks in Greek Literature”. Society and Politics of Southern Europe.11. (1): 50.]

Instead of the term “Muslim Albanians”, Greek nationalist histories use the more familiar but derogatory term, “Turkalbans”.

But who are the Turks and what does the DNA of the population in the Turkish state show?

Genetic evidence against the national myth according to the article by ‘greekherald’. Genetics ignores national narratives; DNA testing has shown that Turkish citizens, mainly come from indigenous populations of the Mediterranean; Italy & the Balkans.

The common haplogroup J2 (24%) found in Turkey is typical of Italians and Greeks – not Asians. Science refutes the idea that modern Turks are primarily of “Turkish” origin.

Cyprus case study:

A comprehensive study by Harvard Medical School showed that Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots share a common pre-Ottoman ancestry.

Crypto-Christianity, forced conversions, and centuries of coexistence resulted in genetic similarities. Most Turkish Cypriots share the same genetic makeup as Greek Cypriots.

Suppression of truth & scientific findings:

Turkish authorities discourage DNA ancestry testing due to its challenge to the official narrative. New laws make questioning “Turkishness” punishable by imprisonment. Science—especially genetics—reveals that many modern Turks have Mediterranean and European roots.

Turkish identity, as currently promoted, is a political myth. Denying genetic reality can lead to cultural backwardness, while embracing it opens the door to future scientific progress.

– https://greekherald.com.au/…/a-look-at-genetics-and…/

Currently, a reprint of sources by 19th-century Greek authors speaks of the Alvanokratia, or Albanian occupation of the Morea as gatekeepers, to suppress the Russo-Greek revolution in the region. According to the authors, Albanian Muslims were hated by Greek elites in the region because Albanians, they said, used violence to gain key roles.

“In a letter to the Grand Vizier, dated 31 August 1770, the governor of Morea, Muhsinzade Mehmed Pasha, expressed his anger at his inability to control the Albanians and requested his transfer to another region. After the suppression of the revolt, the Albanians did not withdraw from the peninsula, but remained for almost a decade. “

This period of the Alvanocracy (period of Albanian rule), as it is known in Greek historiography, was marked by the marginalization of the pre-1770 elites, Muslim and non-Muslim alike, by a new class of Albanian strongmen, whose main characteristic seemed to be a culture of violence and brutality.

– 2007: The Ottoman Empire, the Balkans, the Greek lands : toward a social and economic history : studies in honor of John C. Alexander.

References