Petrit Latifi

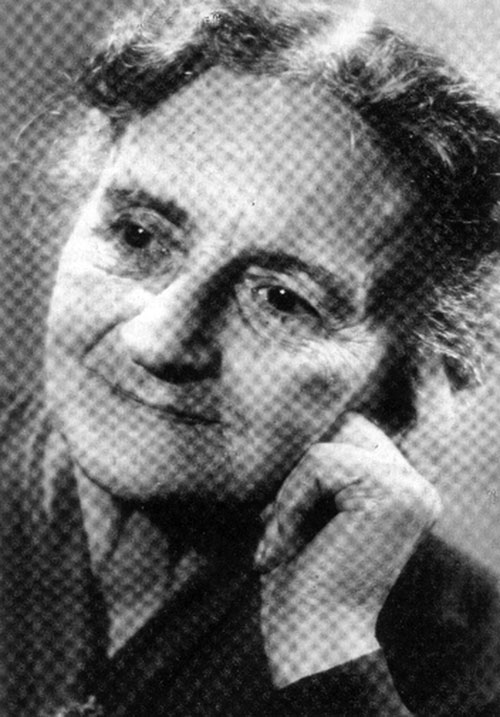

Photo of Marie Amelle Frelin von Godin. Source: Elsie

In 1914, traveler Marie Amelle Frelin von Godin published a report where she writes that 100,000 Albanian civilians had to flee from the mountains due to Serb, Montenegrin and Greek atrocities in 1914. In Shkodër, the refugees numbered 15,000, Kruja, 6,000, in Elbasan 10,000, and in Tirana and the surrounding area, 12,000. In Dibra, 15,000 Albanians were left homeless after the Serbs burned their homes. The author also states that the Serbs would massacre wounded Albanians in their homes. The total numbering 158,000 refugees.

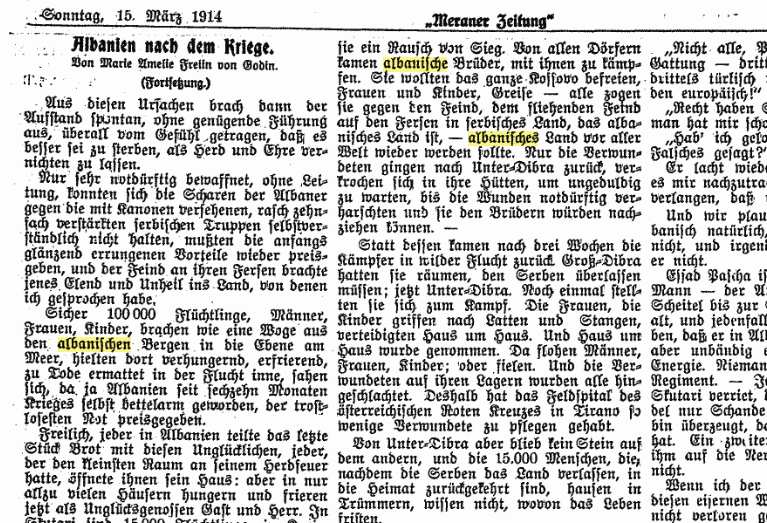

“Albania after the war. Don Marie Amelle Frelin von Godin.

For these reasons, the uprising broke out spontaneously, without sufficient leadership, driven everywhere by the feeling that it was better to die than to let their loyalty and honor be destroyed.

Only very poorly armed, without support, the Albanian troops could naturally not hold out against the cannon-equipped Albanian troops, which had quickly been reinforced tenfold. They had to give up the advantages they had initially brilliantly gained, and the enemy at their heels brought the darkness and disaster into the country of which I have spoken

At least 100,000 refugees, men, women, and children, burst like an arch from the Albanian mountains onto the plains by the sea, then stopped in their flight, starving, freezing, and exhausted, and found themselves exposed to the most desperate hardship, since Albania itself had become destitute after sixteen months of war.

Of course, everyone in Albania shared their last bread with these unfortunates, everyone with the smallest space by their fire opened their house to them: but in all too many houses, hungry and freezing, they were guests and masters as fellow misfortune-seekers. In Sutari there were 15,000, 6,000, in Elbasan 10,000, and in Tirana and the surrounding area 12,000.

Dibra, or Dibra e madhe (Great Dibra), came to Serbia, although no other than Albanian souls breathe there. Not a single Slav, Wallachian, or Greek lives in this once rich, beautiful, and commercial city. But the communities around Dibra, Dibra e vogel. Dibra, with about 20,000 souls, came to Albania.

These people have no other market than that of Dibra e madhe to sell their products, as they are separated from every other city by almost insurmountable mountains, which are completely impassable due to snow for seven months of the year

Serbs were also here at the border, offering the possibility of a tolerable life in exchange for the booty from Lower Dibra. Since ancient times, however, the people from the area around Dibra have been warlike and daring, familiar with rifles and knives like no other part of the population of Albania.

They banded together; they knew that many Albanian brothers on the Serbian border were suffering from similar hardships; they knew that they, too, were about to turn against the enemy; they knew that their Albanian compatriots on Serbian territory now had to endure, bear, and endure much harder. That is why they marched to Greater Dibra with rifles, knives, and axes.

There, the Albanians were well-armed and couldn’t help them at first, but years. Over Serbs, there weren’t that many, and the few were taken by surprise by the shred. So they took the booty from Lower Dibra, the magnificent, rich Dibra e madhe. And it seized them a rush of victory. Albanian brothers from all the villages gathered to fight with them.

They wanted to liberate all of Kosovo; women and children, old people, all of them marched against the enemy, on the heels of the fleeing field into Serbian land, which is Albanian land, should become Albanian land again before the whole world. Only the survivors returned to Lower Dibra, hid in their huts, and waited impatiently until their wounds had healed somewhat and they could join their brothers.

Instead, after three weeks, the fighters returned in wild flight. They had to evacuate Greater Dibra and leave it to the Serbs; now Lower Dibra. Once again they stood up for battle. The women and children grabbed saddles and poles, defending house after house. And house after house was taken. Then men, women, and children fled; others fell. And the wounded on their beds were all slaughtered. That is why the field hospital of the Austrian National Cross in Tirano had so few wounded to care for.

But in Lower Dibra, not a stone was left standing, and the 15,000 people who returned home after the Serbs left the country live in ruins and do not know how they survive. I myself spoke to the Austrian General Staff officer who has traveled the area and said that if no relief expedition with food is sent to Dibra by mid-February, then none of these 15,000 will survive the spring.

Who wants to know what happened in Dibra over there, across the border? The refugees in Tirana are asking themselves with fearful eyes. What happened to their houses, their warehouses? It’s better that no one knows the news, so that a little hope still lives, senseless and hopeless, but it lives.

When we landed in Durazzo, no one yet suspected the misery. Above the blue bay with its belt of lagoons, its wide wreath of mountains, over which the white ridge of the Zomor gleams, separating Kavaja from the rest of the mountains, like a laughing magic greeting from sunny South Albania, the old, angular city rises. At first, everything seems as it used to be. But then one encounters Essad Pasha’s gendarmes everywhere; and then there, in front of the government building, is the bodyguard of the Almighty”.

Marie Amelle Frelin von Godin prepared the Albanian Declaration of Independence and worked a medic in a military hospital in Durrës.

“[…] In the following years, Godin was in Albania for long stays, reporting regularly from and about Albania. Remarkably, Godin was involved in the preparations for the Albanian Declaration of Independence (28 November 1912). During the July 1914 uprising, she worked as a medic in a military hospital in Durres and became seriously ill. After World War I, she settled in Bavaria and picked up her journalistic work and her work for charities. This was also the period when she translated from French and composed novels.”1

References