Written by Col Mehmeti. Translation Petrit Latifi. Taken from the publication “Kulturë”.

In this article by Col Mehmeti we can find an interesting passage on the history of Bajë or Baja region and church.

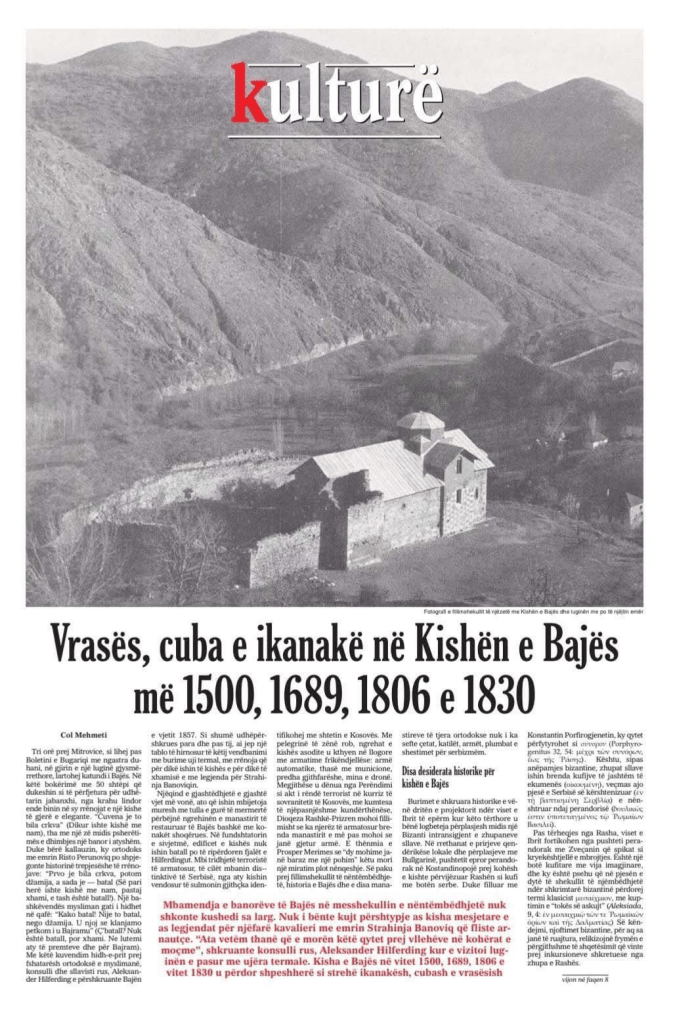

Photo: Early twentieth century photograph of the Church of Baja and the valley of the same name

Page 7:

“Three hours from Mitrovica, as Boletini and Bugariqi were left behind with their smokestacks, in the middle of a semi-circular valley, the village of Baja rose. In this idyll of 50 houses that seemed like a haven for the foreign traveler, the ruins of a large and elegant church still stood out from the eastern side. “It was a famous church once,” said a local resident in a voice between sighs and pain.

Acting as a guide, this Orthodox man named Risto Perunović was explaining the three-part story of the ruins: “First there was a church, then a mosque, and now it’s a battle!” A Muslim neighbor almost jumped on his neck: “Kako batal! Nije to batal, nego džamija. “U njoj se klanjamo petkom i u Bajramu” (What a battle? It is not a battle, but a mosque. We pray there on Fridays and on Eid).

With this impromptu gathering of Orthodox and Muslim villagers, the Russian consul and Slavist, Aleksandr Hilferding, described Baja in 1857. Like many travel writers before and after him, he paints a gloomy picture of this settlement with thermal springs, with ruins that some say were of a church and others of a mosque, and with legends about Strahija Banović.

One hundred and sixty-six years later, what were the remains of brick and marble walls make up the restored Baja monastery complex, along with the accompanying quarters. At the end of September this year, the church buildings were no battle, to use Hilferding’s words. Over thirty armed terrorists, wearing Serbian agents, from there they had decided to attack everything identified with the state of Kosovo.

With the pilgrims taken prisoner, the church buildings were immediately turned into trenches with terrifying weapons: automatic weapons, bags of ammunition, all kinds of shells, mines and drones. Although it was condemned by the West as a serious terrorist act at the expense of Kosovo’s sovereignty, with successive contradictory statements, the Diocese of Raska-Prizren initially denied that there were armed people inside the monastery and then denied that weapons had been found.

Prosper Merimee’s statement that “two denials equal one affirmation” received a mocking approval here. At least since the beginning of the nineteenth century, the history of Baja and some other Orthodox monasteries has not been without squads, slaughterhouses, weapons, bullets and debates about Serbism.”

“Some historical wishes for the church of Baja

Written historical sources put the spotlight on the Upper Ibar region when these crossroads became the battlegrounds of clashes between an intransigent Byzantium and the Slavic zhupans. In the circumstances of local nationalist tendencies and clashes with Bulgaria, the imperial power in Constantinople had long since delineated Rasha as the border with the Serbian world. Starting with

Constantine Porphyrogenitus, this city is depicted as a σύνορον (Porphyro-genitus 32, 54: μέξρι των συνόρων, ἕως τῆς Ῥάσης). Thus, according to the Byzantine view, the Slavic zhupans were within the outer borders of the ecumenical community (oikoumenē), especially that part of Christianized Serbia (ev τη βαπτισμένη Σερβλία) subordinated to the empire (δουλικώς ἐστιν ὑποτεταγμένος τῷ Ρωμαίων Βασιλεί).

After the withdrawal of Rasha, the Ibar region was fortified by the Pera-Ndorak power, with Zvečan standing out as the main stronghold of defense. It was a border world with imaginary lines, and this is why in the second half of the eleventh century, Byzantine writers used the classicist term έμαιχμιον, meaning “no man’s land” (Alexiada, 9, 4: ἐν έμαιχμιώ τών τε Ῥωμαϊκών ὀρίων καὶ τῆς Δαλματίας). Therefore, Byzantine reports, to the extent that they are preserved, relict the general spirit of concern that came from the devastating incursions from the Rasha region.

The memory of the inhabitants of Baja in the mid-nineteenth century did not go far. Neither the medieval church nor the legends about a certain knight named Strahinja Banović who spoke Arnautče made an impression on anyone. “They only said that they took this city from the Vlachs in ancient times,” wrote the Russian consul, Alexander Hilferding, when he visited the valley rich in thermal waters. The church of Baja in the years 1500, 1689, 1806 and 1830 was often used as a shelter for fugitives, cuba (bandits) and murderers”