Introduction

The start of the modern Greek nation in the 19th century brought together many communities from the Ottoman Empire. Among these were Albanian-speaking (Arvanite) populations inhabiting areas later invaded by Greece, notably southern Greece (Attica, Boeotia, the Peloponnese) and Epirus, and Ioannina.

Over the course of several centuries these populations underwent a gradual process of Hellenization, changing their identity from Arvanite or Albanian to Greek.

By the Ottoman era, Albanian dialects (Arvanitika) were widely spoken in:

- Attica and Boeotia (including the countryside around Athens);

- Euboea and parts of the Peloponnese;

- and to a lesser extent, Thessaly.

(See: Balta, 1994; Trudgill, 2002.)

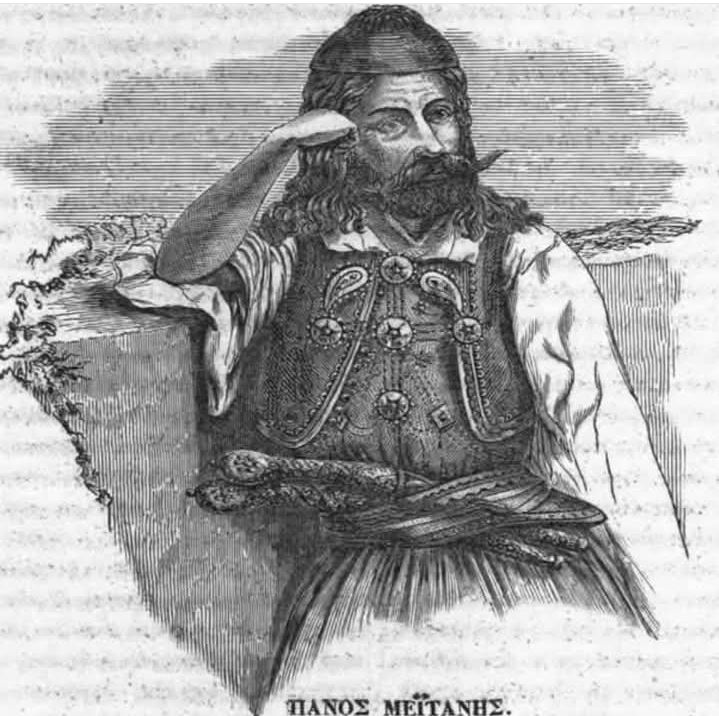

Although they spoke Albanian, these communities were Orthodox Christians and participated fully in the Greek Orthodox religious life. During the Greek War of Independence (1821–1829), many Albanin Arvanites fought as leading figures in the uprising, such as Markos Botsaris and Laskarina Bouboulina.

Epirus and Ioannina: between Albanian and Greek

The Epirus region, stretching from Preveza to Gjirokastër, had long been an Albanian-Greek highway. Ottoman records and Western travellers describe it as inhabited by both Greeks and Albanians.

In the early 19th century, Ioannina flourished under Ali Pasha of Tepelena. Ioannina, although an Albanian center, became a center of Greek education and culture, despite many of its residents being bilingual in Greek and Albanian (Clogg, 1992; Skendi, 1967).

When Greece desired to expand on Epirus after the Congress of Berlin (1878), the citys demographics became politically challenged. European diplomats described Ioannina as largely Albanian-speaking.

The process of Hellenization

The integration of Albanian communities into the Greek nation occurred through Hellenization and Greekification as well as ethnic cleansing and atrocities.

- Religion as a marker of nationality

The Greek Church and state equated Orthodox Christianity with “Greekness.” Albanian Christians were therefore considered members of the Greek ethnos (Herzfeld, 1987). - Education and linguistic shift

Expanding networks of 19th century Hellenism, both in Epirus and in Arvanitic areas of southern Greece, forced bilingualism and eventually Greek assimilation. Albanian ceased to be used publicly or taught in schools (Tsitsipis, 1998). - National ideology and historiography

Greek intellectuals such as Spyridon Zambelios and Konstantinos Paparrigopoulos propagated for a “national narrative” linking all Orthodox peoples of the Byzantine tradition to Hellenic ancestry, effectively focusing nationality around religion and historical consciousness rather than language (Kitromilides, 1989).

Decline of the Albanian language

By the early 20th century, Arvanitika survived mainly in rural communities of Attica, Boeotia, and the Peloponnese, though increasingly marginalized as a “peasant language” by Greek chauvinists. In Epirus, Albanian Orthodox communities gradually adopted Greek, while Muslim Albanians (Chams) were expelled during and after World War II, completing the violent Hellenization of the region (Baltsiotis, 2011). Ioannina itself, once Albanian, became a symbol of Greek culture and education.

Conclusion

The transformation of Epirus and southern Greece from largely Albanian-speaking to Greek-speaking regions was not simply a matter of coercion but of gradual cultural integration. Religion, education, and the institutions of the modern Greek state created a new definition of “Greekness” that could swallow non-Greeks and Albanians.

Bibliography

- Balta, Evangelia. Arvanites and Arvanitika: The Albanian-Speaking Population of Greece. Athens: Cultural Foundation of the National Bank, 1994.

- Baltsiotis, Lambros. “The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece: The Grounds for the Expulsion of a ‘Non-existent’ Minority Community.” European Journal of Turkish Studies 12 (2011).

- Clogg, Richard. A Concise History of Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Herzfeld, Michael. Anthropology Through the Looking-Glass: Critical Ethnography in the Margins of Europe. Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- Kitromilides, Paschalis. “ ‘Imagined Communities’ and the Origins of the National Question in the Balkans.” European History Quarterly 19, no. 2 (1989): 149–192.

- Skendi, Stavro. The Albanian National Awakening, 1878–1912. Princeton University Press, 1967.

- Trudgill, Peter. Language and Nationalism in Europe. Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Tsitsipis, Lukas. A Linguistic Anthropology of Praxis and Language Shift: Arvanitika (Albanian) and Greek in Contact. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998.