Summary:

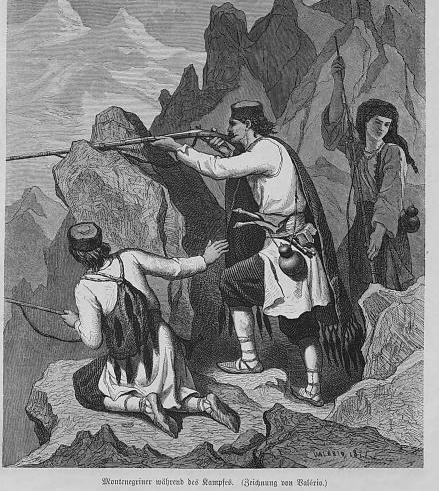

This article, published in Der Sammler (Vol. 31, 1862) and citing the Weser Zeitung, offers a vivid glimpse into the poverty and misery that afflicted Montenegro during its expansionist war against the Pashalik of Shkodër. Despite contemporary reports describing Montenegrin civilians clothed in rags and dying from disease, heat, thirst, and starvation, the Prince of Montenegro nevertheless deemed it fit to wage war on the Ottoman Empire in the hope of acquiring new territories.

Montenegros expansionist war

This war ended partly when Omer Pasha Lata invaded and pillaged Montenegro forcing them to sign a peace treaty, on August 31, 1862, with the conditions they decrease military capacity. After this defeat, Montenegrin bandits – hired once again by Prince Danilo – started plundering the Albanian regions of Vranina, Lesendro, Grudi, Hoti and Tuzi. Austrian diplomats at the time described these raids committed by “banditi montenegrini” quietly supported by Cetinje.

Cited from the article:

“The Weser Zeitung from Vienna reports on August 2 that the battle between the Turks and the Montenegrins, which appears to have been decisive, took place on Friday afternoon, July 18. Omer Pasha, with the three corps of Abdi Pasha, Dervish Pasha, and Hussein Pasha, totaling approximately 50,000 men, attacked the combined Montenegrin forces under Prince Mirko Petrović and Vukotić, numbering about 15,000 men, between Duga Luka and Tuzi, on the line of Bijelo Polje and Pavlovići.

This time the Turks fought with the greatest fearlessness and charged with bayonets against the almost impregnable enemy position, which they finally captured on Saturday evening, July 19. However, they suffered losses of approximately 2,000 dead and just as many wounded or missing. The Montenegrins, who also lost around 400 men, retreated to the strong defensive line of Žagari (Zagarač), which they had already fortified earlier.

After abandoning the Bijelo Polje and Pavlovići positions, they passed through a mountain range, and the Turks did not dare pursue them there. Immediately after securing the Bijelo Polje–Pavlovići line, Omer Pasha began reinforcing it with entrenchments. On Monday, July 21, however, he advanced toward Žagari, and a new, furious battle ensued, the outcome of which was not yet officially reported.

On the plain, it was said that the Turks had been unable to dislodge the enemy from his new position. But anyone who knows the circumstances of the war, the fighting style, and the character of the combatants must consider Montenegro’s situation desperate. To explain this sudden turn of events, the word “exhaustion” suffices, for if 1,000 Turks and 100 Montenegrins remain, the loss is far more severe for the latter, since the Turks constantly receive reinforcements, while the Montenegrins must face the same fire with dwindling numbers.

Since the beginning of the war, around 8,000 Montenegrins have already perished. Montenegro has exhausted its last reserves, and even old men over sixty and boys under fourteen are among the fighters. Typhus threatens both armies, as masses of unburied corpses in the heat are polluting the air. The Turkish hospitals are overflowing, and thousands have already died.

But the Montenegrins, too, cannot endure such hardships indefinitely. The sun beats down on the bare rocks with terrible intensity — there is almost no shade or tree to be found. Added to the misery is an extreme water shortage; over forty men have already died of sunstroke. Night brings little relief: after suffocatingly hot days, the nights are bitterly cold. The soldiers are poorly clothed; without exaggeration, nearly a third of the Montenegrins have no shirts, only a single garment.

From the cold or storms, many die even without combat. Fever is common, striking so violently that the afflicted remain unfit for days. Since the retreat began, an eyewitness reports, an oppressive silence has descended upon Cetinje. Desolation reigns. No one dares speak of the army, much less of the future. The Prince — long resigned to his unhappy fate — has even prevented Darinka, the widow of Prince Danilo, from leaving Paris to return to Montenegro and share the fate of her people.

He wanders about dejected and pensive. Telegrams are constantly sent; almost daily dispatches reach the Russian and French consuls, all identical in content, demanding aid. All hope now rests on Russia. The dispatch from France to Mirko was very inconvenient for Montenegrin interests, and lately communications have also been sent to Lerin (Florina).

In Cetinje, people speak poorly of Serbia, blaming jealousy for its slow action. It is even said that the Prince considers moving to another city, probably Cattaro (Kotor). Preparations are already underway to secure the archives, the treasury, the Prince’s personal effects, and the relics of two saints. The Montenegrins seem to have money, but suffer a great lack of ammunition. Rumors of an impending ceasefire circulate, though they sound unlikely at this moment. One wonders how long the Great Powers will permit this barbaric and utterly senseless war to continue.”