Author: Suad K. Zoranić. Translation Petrit Latifi. 14.11.2025

Summary: The Mountaineers (Malësorë) were Albanian tribes from northern Albania and Montenegro, mainly Kelmendi and Shkreli, some of whom were relocated to Sandžak by the Ottomans around 1700. Over time, they assimilated: those in Muslim-majority areas adopted Islam and the Slavic language, later identifying as Bosniaks; those in Christian areas converted to Orthodoxy and became part of the Serbian population. Families such as Prekić, Ćope, Prdonjić and Nikolić preserve memories of highland origins. Although largely absorbed into Bosniak or Serbian identities, cultural traces remain in surnames, legends and local traditions.

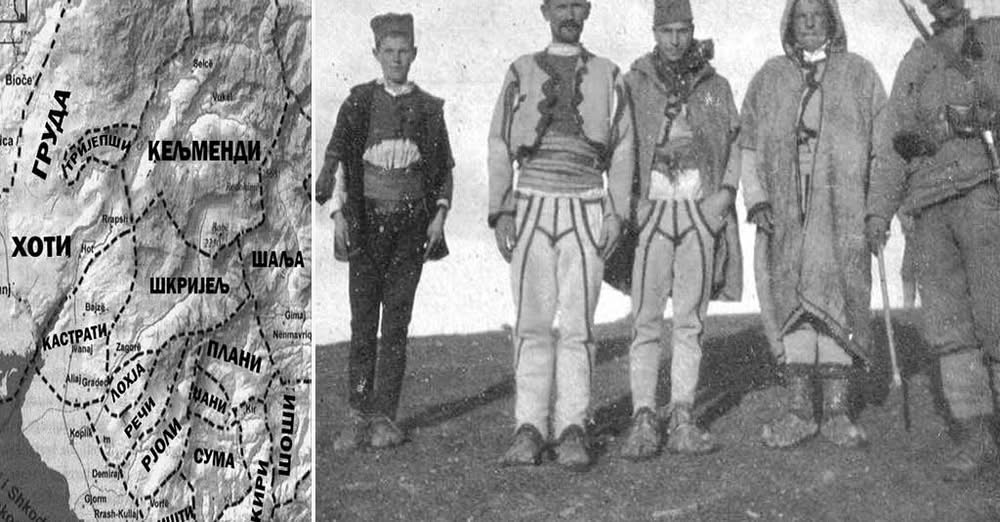

The term Mountaineers (Alb. Malësorë, meaning “mountain dwellers”) refers to the traditional Albanian tribes settled in the mountainous area of northern Albania and Montenegro, historically known as Malësia. Among the largest tribes in this region were the Kelmendi (Klimenti) and Shkreli, branches of which, during the Ottoman period, also migrated to the Sandzak region.

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, due to Ottoman wars and demographic policies, large migrations of Mountaineers to Sandzak were recorded. In 1700, the Ottoman authorities, in an attempt to control the rebellious tribes, relocated about 251 families of the Kelmendi tribe (about 2,000 people) to the Peshter Plateau. According to contemporary sources, even the Kelmendi chieftain converted to Islam under pressure and vowed to impose the new religion on his fellow tribesmen.

Most of these expelled Kelmendi attempted to return to their lands: in 1705 they managed to break the Ottoman blockade, while in 1711 they organized a large armed expedition to Peshter to recapture the rest of the displaced tribe.

⸻

Gradual assimilation of the Kelmendi and Shkreli in the Sandzak

The Kelmendi who remained in Peshter gradually converted to Islam, and by the beginning of the 19th century were completely Islamized. Also, over time, they still abandoned their native Albanian language and adopted the Slavic dialect of the region, becoming Slavophones in the generations that followed.

A similar process occurred with branches of the Shkreli clan, some of whom settled in the Sandžak after 1700 (through Rugova of Kosovo) and accepted Islam in the 18th century, eventually assimilating into Slavic culture and language. As a result, most of the descendants of the Shkreli and Kelmends in the Sandžak today identify as Bosniaks (with the Islamic religion and Slavic language).

However, a part of the incoming Mountaineers remained Christian and over time merged within the Serbian Orthodox population. Ethnological records mention, for example, the Ćilerdžić family, descendants of the Shkreli clan who preserved the Christian religion. Such “Serbized” Mountaineers are still found today in some villages of Tutin and Novi Pazar.

⸻

Prekić and Ćope (village Dolovo, municipality of Tutin)

Descendants of the Shkreli clan still live in the village of Dolovo in Peshter. According to anthropologist Milisav Lutovac (1957), there are five houses in Dolovo belonging to the Prekić family, originally from Shkreli. Their ancestors were among the first inhabitants of the area, initially in the Debeljak neighborhood, and later moved to other parts of the village.

The surname Prekić is thought to derive from the Albanian name Preka (short for Prenk, i.e. Frang), which indicates a former connection with the Catholic tradition. Over the centuries, the family changed its religious and ethnic identity: today most of them are Muslim and identify as Bosniaks, although they retain memories of their Albanian origin.

A branch of this family moved to Toplica (Serbia) at the end of the 19th century: the Ćulafić (later Milić) family from the village of Zdravinje near Prokuplje comes from the Prekići of Dolovo. That branch adopted Orthodox Christianity and today celebrates Saint Nicholas, while the remaining part in Peshter became completely Islamized and no longer practices Christian traditions.

The Ćope family, a branch of the Prekići, is found in Dolovo and the surrounding villages. They also originate from Shkreli, are today Muslim and identify as Bosniaks, but the old Albanian tradition is preserved in family legends.

⸻

Prdonjić, Nikić, Nikolić and Milosavljević

(Rajetiće village, Novi Pazar)

The mountain village of Rajetiće is a settlement where several Serbian Orthodox families of Kelmendi descent live today. According to the research of Petar Ž. Petrović (Raška, 2010), there are four families with this origin in Rajetići: Prdonjići, Nikići, Nikolići and Milosavljevići. All of them celebrate Saint Stephen as a family holy day (krsna slava).

According to popular folklore, these are “Serbized Klimenti”, i.e. Serbian families today, but originating from the Albanian Kelmendi tribe. They have fully integrated into the Serbian community: they speak Serbian, are Orthodox and practice Serbian traditions, while preserving only some elements of the highland heritage in the family memory.

Their surnames, formed from the names of their ancestors (Nikola → Nikić/Nikolić, Milosav → Milosavljević), suggest that at the time of settling in Rajetići they were already baptized in the Orthodox faith. It is possible that their ancestors from Kelmendi converted to Orthodoxy earlier, in the 18th century or at the beginning of the 19th century.

⸻

Slava – the stigma of assimilation

Slava, the Serbian tradition of honoring the family saint, became a sign of identity for the Malësors who accepted Orthodox Christianity. For example, all Kelmendese families of Rajetića today celebrate Saint Stephen, which shows that they come from the same stock.

Meanwhile, the Prekiqs and Ćopes, being Muslims, do not celebrate the Slava, but their branches that migrated to Serbia (the Milić family) celebrate Saint Nicholas, one of the most widespread Serbian Slavs.

⸻

Ethnic transformation: from Albanian Catholics to Bosniaks and Serbs

The process of ethnic transformation of these families took place gradually. The initially Catholic mountaineers (or Bogomils in some areas) accepted Islam if they settled in an area with a Muslim majority – as in Peshter – later becoming part of the Bosnian identity.

Those who settled in Christian environments, either joined the Austrian army during 1737, or settled in surrounding Serbian villages, accepted Orthodox Christianity and were Serbified over the centuries.

Many of them preserved elements of Albanian culture in wedding customs, old names, physiology or folklore. Today, these lineages are studied mainly through archival sources, genetic research and ethnological data.

⸻

The spread of the Highlanders throughout the Sandzak and beyond

The phenomenon of families with highland origins is not limited to Tut and Novi Pazar. The massive migrations of the 18th century left their mark on the entire region. Ethnographer Milisav Lutovac points out that the Rozhaja area and parts of the Sandzak are widely inhabited by descendants of the Kelmends. The Dacić family in Rozhaja, for example, comes from the Kelmend tribe.

In Peshter and Sjenica, there are also families descended from the Hot, Gruda, and even Dukagjin groups.

In Bihor (Bijelo Polje and Petnjica) many Bosniak families retain names or nicknames derived from Albanian tribes – the widespread surname Shkrijelj is directly related to Shkreli.

There are also Orthodox mountain families in Eastern Herzegovina, which today are fully part of the Serbian population.

⸻

Conclusion

The mountaineers, although in smaller numbers compared to the general population, have played an important role in the ethnogenesis and cultural mosaic of Sandžak. Their descendants today are mostly assimilated as Bosniaks or Serbs, but in many families, memories of their mountain origins still live on – whether in a surname, in an inherited story or in a new interest in genealogy.

⸻

Reference

Academic and historical sources that attest to the presence and heritage of the Malësors in Sandžak were used in the preparation of this article, including Jovan Tomič’s studies of the Kelmends in Peshter, the ethnographic work of Milisav Lutovc (Rožaje i Štavica, SANU 1957), and the monograph Raška (Petar Ž. Petrović, 2010). Data from the genealogical project Poreklo.rs and traditional stories collected from local historiography were also consulted.

Original article