By Ilmi Veliu. Translation Petrit Latifi

ARNAUTI ISKENDER – Ottoman documents that speak about Skanderbeg’s Albanian origin

Although the works of early Ottoman chroniclers were mostly written by official court historians — often showing a hostile attitude toward Albanians — they still provide valuable information about Skanderbeg, the Kastrioti family, and their Albanian origin. In several cases, these Ottoman sources preserve details that do not appear in non-Ottoman writings.

The authors of these works, while naturally focusing on the deeds of sultans and Ottoman commanders, also include information based on their own memories or on stories from people who lived through the events. Their texts give precise descriptions of Skanderbeg and the Albanian population.

Below are the most important Ottoman sources that mention Skanderbeg’s Albanian identity.

Oruç bin Adil

Author of Tevari el Osman, one of the oldest Ottoman histories. Manuscripts were found in Oxford and Cambridge and later published by Franz Babinger.

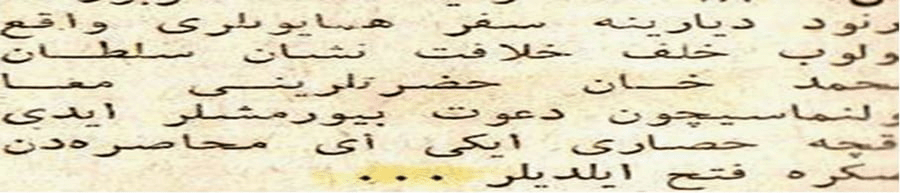

Oruç describes the many campaigns against Skanderbeg and notes explicitly that the Sultan went to fight in Albanian lands (“Arnavud Ili”), not in Greece, Macedonia, or Serbia. He repeatedly refers to the region as the “Vilayet of the Albanians.”

He writes that Ali Bey, son of Evrenoz Bey, entered the Albanian vilayet to fight against Iskender, and that Sultan Murad II sent forces to capture Sfetigrad in Albanian territory. Oruç consistently uses the title “Arnavud beg Iskender” — meaning “Iskender, lord of the Albanians.”

He also mentions the “land of Juvan” (the principality of Gjon Kastrioti) and says that Murad II invaded it but failed to take Kruja.

Anonymous Ottoman Chronicles (Tevarih el Osman)

This collection consists of numerous late-15th- and early-16th-century chronicles, published by Franz Giese.

They describe the principality of Gjon Kastrioti as Albanian land and recount how Ali Bey plundered the “Albanian vilayet.” Skanderbeg is consistently called “the Albanian ruler.”

When describing the campaigns of 1450, 1466 and 1467, the chronicles state clearly that the war was fought against Albanians under their Albanian lord, Iskender.

One passage describes Albanian territory as extremely mountainous, with fortresses perched on cliffs and narrow, dangerous paths that even crows could not pass over.

Ashik Pasha Zade

A 15th-century Ottoman chronicler.

He refers to Iskender as “an Arnaut (Albanian)” and calls him “the son of the Albanian ruler.” He notes that Iskender had been raised as a page in the Sultan’s court before rebelling.

Thus Pasha Zade confirms both Skanderbeg’s Albanian ethnicity and his descent from an Albanian ruling family.

Mehmet Neshri

A historian and poet of the era of Sultan Selim I.

Neshri mentions Albanians participating in the Battle of Kosovo alongside Hungarians, Vlachs, Czechs, and Bulgarians.

In a chapter titled “The War with the Albanians,” he calls Skanderbeg “Iskender arnavud beg” (Iskender, the Albanian lord). He writes that Iskender rebelled, moved through the mountains near Tetovo, and later fled via Durrës to Italy.

Dursun Beg

Historian of Sultan Mehmed II.

He writes that the “ungrateful Albanian population” rose in rebellion under Iskender. After punishing Franks and Hungarians, the Sultan planned to crush the “ungrateful Albanians” under “Arnaut Iskender.”

Despite this hostile tone, Dursun Beg confirms Skanderbeg’s Albanian identity multiple times. He describes the Albanian lands as rugged and difficult even for “Alexander the Great” to penetrate, and says that Iskender returned to his father’s homeland claiming: “I am the son of your ruler.”

Idris Bitlisi

A Persian scholar who joined the Ottoman court in 1501.

Bitlisi mentions the ruler of Shkodra, “George,” and refers to Skanderbeg as “the Albanian Iskender”, one of the most trusted men in the Sultan’s service. He praises Albanians as naturally brave and fierce.

He writes that Iskender, raised with great care at court, eventually left to return to his own homeland and rule his people — a detail confirming that he was known to be Albanian even at the Ottoman court.

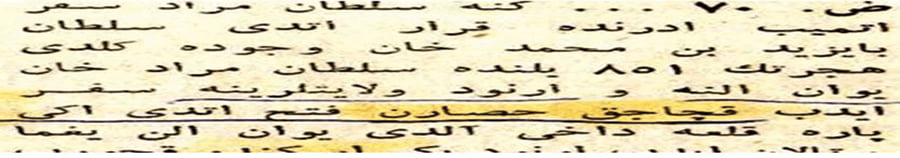

Kemal Pasha Zade

Son of a commander who fought at the conquest of Constantinople.

He writes that in the land of the Albanians there appeared a man “from an old royal lineage — the son of Juvan — by the name of Iskender.”

He later notes that this “Arnaut Iskender” was welcomed by the people into his father’s vilayet and became king of the Albanians.

Hoxha Sadedini

One of the most respected Ottoman historians.

He writes that “the Albanian ruler had a handsome son named Iskender,” describing his appearance in unusually flattering detail. He notes that Iskender was sent to the Ottoman capital as a sign of loyalty.

This is one of the rare Ottoman passages describing Skanderbeg’s physical appearance.

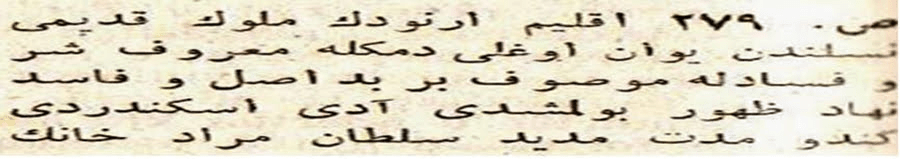

Ali Mustafa bin Ahmed

Secretary of the imperial council and author of Kunhul Ahbar.

He refers to Hamza Kastrioti as “the grandson of the Albanian Iskender,” again affirming Skanderbeg’s Albanian identity.

Elsewhere he calls Iskender “a worthless man of the Albanian tribe,” showing hostility yet clearly identifying him as Albanian. He also writes that Iskender was the son of “one of the bandits of that evil people” — again referring to Albanians.

Conclusion

Across a wide range of Ottoman sources — historians, chroniclers, poets, and court officials — Skanderbeg is consistently described as Albanian. The texts repeatedly call him:

- Arnaut / Arnavud (the Ottoman term for Albanians)

- Albanian lord

- Son of the Albanian ruler

- Ruler of the Albanians

None of these sources suggest a Slavic, Serbian, Greek, or Macedonian origin. Even when hostile, the authors still identify him as unmistakably Albanian.