Image taken from Dardaniapress.com

Torbesh

Macedonian Muslims (Macedonian: Македонци-муслимани, Makedonci-muslimani), also known as Muslim Macedonians or Torbesh, (Macedonian: Торбеш) and in older origins grouped together with the Pomaks, are a religious minority group within the ethnic Macedonian community who are Muslims (mainly Sunni, although Shia is widespread among the population).

They are culturally distinct from the majority Macedonian Orthodox Christian community, and are linguistically separated from larger ethnic Muslim groups in North Macedonia such as Albanians, Turks, and Roma. The regions inhabited by these Slavic-speaking Muslims are the Dibra Voivodeship, Drimkol, Reka e Poshtme, and Golloborda (in Albania).

Origins

Macedonian Muslims are mainly descendants of Slavic and Orthodox Christians from the region of Macedonia who converted to Islam during the centuries when the Ottoman Empire ruled the Balkans. Various Sufi orders (such as the Khalwati, Rifa’i and Kadiris) all played a role in the conversion of Macedonians and the Paulician population.

Turkish academic and folklore expert Yaşar Kalafat, in his 1994 comparative research on folk culture in Turkey and the Balkans, noted many similarities between some of these communities, especially the Torbesh, and the Turks of Turkey and concluded that most Macedonian Muslims share the same pre-Islamic Turkic traditions and beliefs and claims that this is evidence that these communities may originally be ethnic Turks or Turkic people who converted to Islam during the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans.

Settlement Areas

The largest concentration of Macedonian Muslims can be found in western North Macedonia and eastern Albania. Most villages in the Dibra region are inhabited by Macedonian Muslims. In the municipality of Struga there is also a large number of Macedonian Muslims who are mainly concentrated in the large village of Llabunishte.

Further north, in the Dibra region, many of the surrounding villages are inhabited by Macedonian Muslims. The Reka e Poshtme region is mainly inhabited by Macedonian Muslims. They form the rest of the population who emigrated to Turkey in the 1950s and 1960s. Places such as Radostushë and Tetovo also have large Macedonian Muslim populations.

The majority of the Turkish population along the western Macedonian border are in fact Macedonian Muslims. Another large concentration of Macedonian Muslims is in the so-called Torbešija which is just south of Skopje. There are also large concentrations of Macedonian Muslims in the central regions of the Republic of Macedonia, around the municipality of Pljevlja and the municipality of Dolneni.

Demographics

The exact number of Macedonian Muslims is not easy to establish. Historian Ivo Banac estimates that in the former Kingdom of Yugoslavia, before World War II, the Macedonian Muslim population stood at around 27,000. Later censuses have produced dramatically different figures: 1,591 in 1953, 3,002 in 1961, 1,248 in 1971 and 39,355 in 1981.

Commentators have suggested that the latter figure includes many people who previously identified themselves as Turks. Meanwhile, the Association of Macedonian Muslims has claimed that since World War II more than 70,000 Macedonian Muslims have been assimilated by other Muslim groups, mostly Albanians. The Macedonian Muslim population in the Republic of Macedonia in 2013 is estimated at 40,000 people.

Language and ethnicity

Like their Christian ethnic kin, Macedonian Muslims speak Macedonian as their first language. Despite their common language and racial heritage, it is almost unheard of for Macedonian Muslims to intermarry with Orthodox Christian Macedonians. Macedonian ethnologists do not consider Muslim Macedonians to be an ethnic group separate from Christian Macedonians, but rather a religious minority within the Macedonian ethnic community. Intermarriage with other Muslim groups in the country (Albanians and Turks) is much more acceptable, given the shared religious and historical ties.

When the Socialist Republic of Macedonia was established in July 1944, the Yugoslav government encouraged Macedonian Muslims to adopt an ethnic Macedonian identity. This has since led to some tensions with the Macedonian Christian community over the widespread associations between Macedonian national identity and adherence to the Macedonian Orthodox Church.

Political activities

The main outlet for political activity by Macedonian Muslims has been the Association of Macedonian Muslims. It was founded in 1970, with the support of the authorities, perhaps as a way to keep them tur aspirations of Muslim Macedonians in check.[

Fear of assimilation into the Albanian Muslim community has been a significant factor in Macedonian Muslim politics, reinforced by the tendency of some Macedonian Muslims to vote for Albanian candidates. In 1990, the head of the Macedonian Muslim Organization, Riza Memedovski, sent an open letter to the leader of the Party for Democratic Prosperity of Macedonia, accusing the party of using religion to promote Albanianism among Muslim Macedonians.

A controversy erupted in 1995 when the Albanian-dominated Meshihat, or Islamic Community Council of North Macedonia, declared Albanian the official language of Muslims in North Macedonia. The decision sparked protests from leaders of the Macedonian Muslim community.

Occupation

Many Macedonian Muslims are engaged in agriculture and also work abroad. Macedonian Muslims are known as fresco painters, woodcarvers, and mosaic makers. In recent decades, a large number of Macedonian Muslims have emigrated to Western Europe and North America.

Avdullah Qazimoski writes:

“The chairman of the Struga municipal council, Avdullah Qazimoski, said on STRUGA TV that the residents of Llabunishte and the villages around it are being played with their identity, calling them both torbesh and Albanian, writes Struga Ekspres.

“They call us torbesh, but we are Albanian, but when they need our support, they tell us that we are Albanian. My grandfather, great-grandfather, grandfather and I are Albanian. And even now, when they see us on TV, they say, “Here is this torbesh.” Struga has benefited from us, while we have lost from Struga. We have always voted for Albanian parties.”1

Gorani

Ismet Azizi: Gorani and Torbesh in Bosnian Perspective: A Critical Analysis of Esad Rahić’s Text

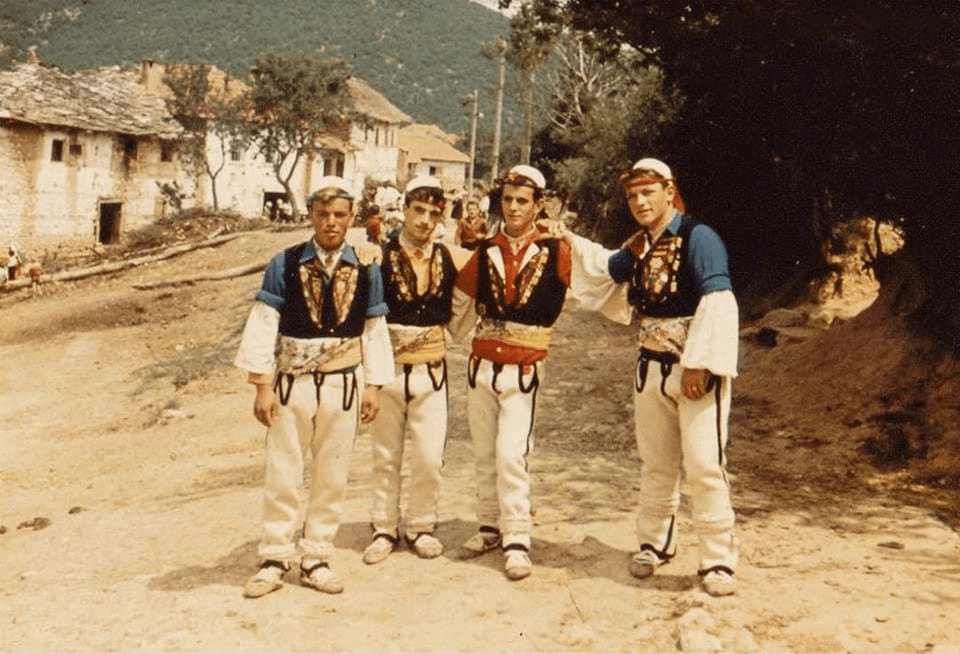

Gorani in Albanian dresses

“In recent years, a strong tendency has emerged in Bosnian academic and political discourse to integrate the non-Albanian Muslim communities of the Balkans – such as the Gorani in Kosovo, the Torbesh in Macedonia and the Pomaks in Bulgaria – into a common Bosnian identity.

A clear example of this tendency is Esad Rahić’s text, which attempts to establish a straight historical line from the medieval Bogomils to today’s Bosniaks. This article aims to provide a critical analysis of this text, highlighting its shortcomings, distortions and biases, especially in relation to the Albanian element and the multifaceted processes of assimilation.

Rahić argues that the “Goranc” identity is an invention of the Milošević regime and the SANU, to separate the Gorani from the “Bosnian body”. Although this is partly true, he forgets that the categories “Muslim” (1971–1991) and “Bosnian” (after 1993) are also political constructs created by the Yugoslav state and then appropriated by Bosnian elites. So, “Gorancs” are no more invented than “Muslims” or “Bosnians”.

In the text, Albanians are presented only as “robbers” of Gorani cattle in the 19th century . The author denies the fact that many villages of Luma and Opoja were Albanianized in the 18th–19th centuries, and that after 1912 the Albanians of Gora were often registered as “Turks” or “Muslims” due to Serbian administrative pressure. Thus, Rahić eliminates the Albanian element from the history of Gora, replacing it with a Bosniakizing narrative.

One of the pillars of the text is the claim that the term “Torbesh” derives from medieval Bogumilism and testifies to the continuity of this community up to today’s Bosniaks. In reality, this is an ideological thesis:

There is no evidence that the term “Torbesh” was used for the Bogumils before the Ottomans; Most scholars see the Islamization of the Gorani as a typical process of the Ottoman period, not as a continuation of medieval heresies; The use of Bogumilism aims to create an “antigenesis” that legitimizes Bosniakization.

Rahić underlines the Slavic and Romance elements in the Gorani language, but does not mention the borrowings from Albanian, which are numerous and indicate long coexistence with Albanians.

When he talks about the change of surnames, he speaks of “Albanization,” but the facts show the opposite: surnames were Serbized (–ić) or Turkized (–ler, –lar, –oğlu) in certain periods, especially during the migrations to Turkey in the 1950s–1960s. The “Albanization” thesis is a distortion.

The author provides with merit evidence of Serbian violence during 1912–1913, including the massacres in Restelica, Kruševo, and Brod, also citing Dimitrije Tucović. But he avoids emphasizing that the main victims were Muslim Albanians, who were often neighbors and related to the Gorani.

Similarly, the Tivar Massacre (1945) is reduced by the author to only “7 inhabitants of Gora,” when it is known that thousands of Albanians and Bosniaks from Kosovo and Sandzak were killed there.

The text ends with the call: “I propose that we remain one people”. This is not a scientific statement, but a political platform for the Bosniakization of the Gorani and Torbesh. The comparison with the Bosniaks of Sandžak is wrong: there the main process was the assimilation of Muslim Albanians, not the preservation of any early “Bosnian” identity.

Esad Rahić’s text is more of an ideological essay than a scientific study. It aims to legitimize a Bosniakization project, minimizing the Albanian element, abusing the concept of Bogomilism, and ignoring the processes of Serbization and Turkization. In reality, the Gorani are a complex Balkan community, with Slavic, Albanian, Turkish, Vlach, and Oriental layers. Their history cannot be reduced to a “branch of the Bosniaks.” Any attempt to impose a single identity on them is part of the policies of assimilation – whether Serbian, Macedonian or Bosnian – which have always undermined their historical authenticity.”

References and sources

- Kowan, J. (2000). Macedonia: The Politics of Identity and Difference. London: Pluto Press. fq. 111. ISBN 0-7453-1594-1.

- Report of the International Commission to Inquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan Wars, published by the Endowment Washington, D.C. 1914, p.28, 155, 288, 317, Лабаури, Дмитрий Олегович. Болгарское национальное движение в Македонии и Фракии в 1894-1908 гг: Идеология, программа, практика политической борьбы, София 2008, с. 184-186, Поп Антов, Христо. Спомени, Скопje 2006, с. 22-23, 28-29, Дедиjeр, Jевто, Нова Србиjа, Београд 1913, с. 229, Петров Гьорче, Материали по изучаванието на Македония, София 1896, с. 475 (Petrov, Giorche.

- Center for Documentation and Information on Minorities in Europe – Southeast Europe (CEDIME-SE).

- Лабаури, Дмитрий Олегович. Болгарское национальное движение в Македонии и Фракии в 1894-1908 гг: Идеология, программа, практика политической борьбы, София 2008, с. 184, Кънчов, Васил. Македония. Етнография и статистика, с. 39-53 (Kanchov, Vasil.

- Fikret Adanir, Die Makedonische Frage: Ihre Entstehung und Entwicklung bis 1908, Wiesbaden 1979 (in Bulgarian: Аданър, Фикрет. Македонският въпрос, София2002, с. 20)

- 52 Makedonya Türkleri arasinda yasayan halk inanclari : Türkmenler, Torbesler Turkbas, Çenkeriler ve Yörükler, p. 18-20, 52, at Google Books

- Banac, Ivo (1989). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. fq. 50. ISBN 0-8014-9493-1

- Poulton, Hugh (1995). Who Are the Macedonians?. C. Hurst & Co. fq. 124.

- Duncan M. Perry, “The Republic of Macedonia: finding its way”, in Politics, Power and the Struggle for Democracy in South-East Europe, ed.

- Hugh Poulton, “Changing Notions of National Identity among Muslims”, in Muslim Identity and the Balkan States, ed.

Sources for Ismet Azizis article

Rahić, Gorans or Gorans – part of the Bosnian people in the diaspora, [pp. 7, 4, 10, 7-8, 9, 11]. https://dardaniapress.net/veshtrime/goranet-dhe-torbeshet-ne-optiken-boshnjake-nje-analize-kritike-e-tekstit-te-esad-rahic/