Authored by Nikos Stylos. Translated and edited by Petrit Latifi.

New evidence from variant letter forms—mirroring Messapian, Illyrian and early Albanian scripts—suggests that Aegean epigraphy may preserve a forgotten Adriatic linguistic layer.

Abstract:

This study examines a 5th-century BC inscription from the island of Milos, traditionally considered unreadable by Greek linguists, and proposes an interpretation linking its alphabetic forms and linguistic features to ancient Albanian/Illyrian and Doric linguistic traditions. The text situates the inscription within the broader archaeological and historical context of Milos, highlights parallels between ancient Cycladic, Doric, Illyrian and Messapian scripts, and presents comparative examples such as amulets, coins, and Etruscan mirrors. Through analysis of variant letters (especially multiple forms of T, S, N), the study argues that the inscription may be read through an Albanian linguistic framework, suggesting deeper cultural and linguistic interactions in the ancient Aegean and Adriatic worlds. Broader implications are drawn for the relationship between Doric, Illyrian, and Cycladic cultures and their writing systems.

Summary:

The text explores a 5th-century BC funerary inscription discovered on the island of Milos, which Greek scholars consider unreadable. The author argues that its alphabetic characteristics—including the presence of variant letters such as multiple forms of T (T and 7), S (S and C), and N—are consistent with features found in ancient Albanian, Illyrian, Messapian, and certain Doric alphabets. To support this claim, the text surveys various archaeological and linguistic materials: pan-shaped Cycladic vessels, wall paintings from Fylakopi, Mycenaean pottery, and coins from Milos, Apollonia, Epidamnos, Damastion, and other Illyrian regions. Additional evidence is drawn from magical amulets, Etruscan mirrors, and early dictionaries documenting variant Albanian letters.

The author proposes a transliteration of the Milos inscription into Albanian and interprets it as a dedication connected to figures such as RIA IS (identified with “New Isis”). A parallel inscription from Messapia (4th–3rd century BC) is likewise interpreted using Albanian phonology, suggesting that the Messapians—historically linked to Illyrian settlers—used a script compatible with Albanian linguistic structures.

The study argues for historical connections between the Cycladic and Illyrian cultures, reinforced by migration patterns, ancient testimonies (Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Herodotus, Hesychius), and the spread of Doric-speaking populations. The author challenges the Greek classification of Doric, Ionian, and other varieties as dialects of Greek, presenting ancient grammatical sources that describe them instead as distinct languages sharing only partial lexical overlap. Overall, the analysis proposes that ancient Albanian/Illyrian linguistic presence in the Aegean has been underestimated and that the Milos inscription may be one of many written remnants reflecting this heritage.

The 5th century BC Arvan inscription from the island of Milos

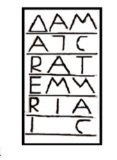

Among the ancient Arvanite inscriptions found on the Aegean islands, one is the following. This inscription, which was found on the island of Milos in the Cyclades and is considered to be an inscription from the 5th century BC, I took it from the Catalog of the exhibition “History of Writing in the World” of 2002, of the University of Athens, where in its content we also find the information: “Simple funerary monument, on which only the name and perhaps the place of origin of the deceased are recorded.”¹ According to this information, we can say that Greek linguists admit that they cannot read this inscription.

5th century BC inscription found on the island of Milos located in the Athens Museum of Inscriptions.

I am writing briefly about the island of Milos, which is located in the southwest of the Cyclades, the distance from Piraeus is 86 nautical miles and is located approximately in the middle of the Piraeus-Crete route. According to archaeological findings, Milos is considered one of the first islands of the Cyclades to be inhabited since the Neolithic Age (7000 BC) and became rich thanks to the exports of obsidian, a black and very hard volcanic stone, which was used to build weapons and tools. This is confirmed by the findings that have been discovered in Thessaly, Peloponnese, Crete, Cyprus, Egypt and other countries.

In the Bronze Age, which lasted for about two millennia, that is, from 3200 to 1100 BC, Milos had a very important place in the Cycladic world, and generally in the Cycladic culture which is divided into three periods: Proto-Cycladic (I and II), Middle and Late Cycladic.

The Paracycladic II period (2800-2300 BC) is known for the development of metallurgy, navigation and communication and is characterized by the development of metal tools and weapons, as well as rowing ships, which we also find represented in pan-shaped ceramic vessels, which are among the most characteristic finds of Paracycladic tombs, and mainly of Syria, one of which is the one shown in the photo below.

Pan-shaped ceramic vessel with an engraved representation of a ship from the Pre-Cycladic II period (2800 – 2300 BC), found at Chalandrianí on the island of Syros.

From the findings presented below on Milos, which date back to the Late Cycladic period, we can see very well the level of civilization that this island had at that time.

A΄. Parts of a wall painting depicting a seascape with flying fish (ulsae). It was found in Fylakopi, Milos and dates to 1600-1500 BC. The wall of the room in which this painting was located belonged to a religious complex. B΄. Ceramic foot. Year of creation around 1600 BC and is located in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

A. Krater found at Eptastomo on Milos, in the Mycenaean period cemetery (1700-1100 BC), in a photograph from the Directorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades. B. Aphrodite of Milos. The famous statue of the Hellenistic period, which was found on Milos in 1820 and is located in the Louvre Museum, Paris.

With the so-called descent of the Dorians from the north, around 1000 BC, Milos was settled by the Dorians, who belonged to the same ethnic group as those who settled in Sparta, but remained independent. From the 6th century BC until the siege of 416 BC by the Athenians, Milos issued its own coinage, and also had its own alphabet, which according to the writings of experts had many influences from Thira and Crete.

With the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) between Athens and Sparta, Milos maintained a certain neutrality, in contrast to the other Dorian cities. In 426 BC the Athenians made their first attack on the island’s countryside and demanded tribute from the Milos, but they refused.

In the summer of 416 BC the Athenians attacked Milos again with 3,400 men and threatened to completely destroy it if it refused to make an alliance with them. The Milos refused once again and the Athenians began the siege in the summer of 415 BC. After the island fell, the Athenians executed all the adult men and sold the women and children into slavery and transferred about 500 of their own settlers to the island.

With the final defeat of Athens (405 BC), the Spartan general Lysander expelled the Athenian inhabitants from Milos and transferred the descendants of the old inhabitants. Sparta made Milo a member of its Federation and established a subordinate government with a Commissioner as commander.

Milo’s inscription clearly written.

Returning to the inscription, which I am repeating and writing clearly, and knowing that one of the problems, and even the most important, that we cannot read most ancient inscriptions, are the alphabets, I feel the need here for some of the letters of this alphabet.

Amulets with the magical four-letter word written in the form SATOR.

Starting with the letter 7, I will simply say that this alphabet has two different Ts, written T and 7. For those who are more interested in this, I will add for information that these two different Ts are also found in the Elbasan alphabet, which, as is known, is one of the many Albanian alphabets, written and V.2

As for the Greek linguists who consider this letter I, and completely ignore the existence of the second T in the old Doric alphabets, from a book published in the first decade of the 19th century, I am bringing this photocopy: Πάται ῥώσατ ἰάνᾳ θα ράντα (The ducks and the geese are falling), as well as the following amulet, where the magical or secret quatrain is written in the Albanian alphabet and Greek letters.

The alphabets in which, as can be seen, the second T is written 7 and 7. Also interesting in the alphabet where the magical or secret tetragrammaton is written is the letter used to write S, that is, the letter C, which in Milo’s inscription is written C.

Amulets with the magical four-letter word written in the form SATOR.

This amulet, which is even the only find with the magical or secret eight written in the Greek alphabet, is known to have been in the Berlin Museum until 1945 and to have been found in Asia Minor.4 As for its dating, although there is no information, due to the small letters we can say that it was written or engraved after the 7th century, when their use began.

Making it my life’s goal, not only to show Albanians that there are many written remains in their language, but also to teach them to read them, regarding the alphabet in which the above amulet is written, making a parenthesis here, I will add that, in addition to the two Ts, T and 7, there are also two S, S (S) and C (SH), as well as two E, C (e) and E (ë), which with the same pronunciation we also find as letters of the Istanbul alphabet.

Without going into the content of the text of the secret tetragram, taking into account the other relevant fragment about its sanctity from Clement of Alexandria: “But even the secret tetragram, which was worn only by those allowed to pass into the inner sanctum, is called iaue, which is translated as being and what will be”.

I will additionally say that this is dedicated to the God Kronos, called by the Greeks and Saturn by the Latins, that even in English the day of Saturday is dedicated to him, whose name in the amulet above in Albanian is written CTWP (SHATOR), and even with omega (w), from which we can also explain the writing of U in the name SATURN, knowing that the letter omega (o) is transcribed as U by the Romans but also by the modern Greeks in many loanwords.

Knowing that the name CRTUP (SHATOR) in the Arbëresh language means “carvers with a hoe”, I also find the information very interesting: «Δευάδαι· οἱ Σατοὶ, ὑπ᾿ Ἰλλυρίων» (Deuadhai; Shatoi, under the Illyrians), which we find in Hesychius’ dictionary. Information according to which, even if the word in the manuscript “Σατοί” was rendered “Σάϊοι” by Hesychius’ publisher Maurikios Smiditos and the others “Σάτυροι”, considering what language the Illyrians spoke, we can very well understand why the Illyrians called “Σατούς” or Shator “Δευάδαι”, since in the Illyrian language, which I equate with ancient Albanian, dheuadhai and dheua dhai mean: and (land) they gave.

Although the issue of ancient alphabets, which has not attracted the attention of Albanology to date, and which in my opinion should take its rightful place in Albanology, I will also clarify that the letter we have in the inscription above is the third N, which we find in many ancient alphabets, one of which is the alphabet where the names are written in the presentation of the Etruscan mirror below, which, like the amulet above, has been lost by a strange coincidence.

Etruscan bronze mirror made in the early 2nd century BC, which was previously in the Janzé collection and is now lost.

Malion

In the representation of the mirror above, as we see, in addition to the letter, we also have two other N, written N and M, which, we can say, were also letters of the Milos alphabet, according to the other coin from this island, where, as we see, the name NA AICN is written, which the Greeks, not wanting to say that it is not Greek, transmit as MALION, and more Greekized MILEON with the explanation that the name of the island of MILOS also derives from it.

Coin of Milo, 5th century BC.

For these additional letters I will say that N is pronounced as N in the Greek and Latin alphabets and as NN in the Arbëresh alphabets, NJ in the Albanian one or GN in Italian and Ç in Spanish, which in many names the Greeks and Latins mistakenly or intentionally write as M, such as in the names NENVE and NENDER, where the first is written by the Greeks as Menelaos and the second by the Latins as Minerva. A certain verification that it is not M is also found in the expression of the mirror above, where, in addition to N, M and, we also have the letter M.

Information about the pronunciation of the letter, i.e. the third N, can be found in the grammar of the Albanian language by J. G. von Hahn, information which, although not entirely accurate, translates as it is written:

“The Greeks also distinguish a third n which coincides exactly with the pronunciation of the French n in on, sans, etc. For this reason, in the dictionary we write it with (n).” 8

Written with the letter (n)”, that is, with the so-called third N of this language, from the Albanian-German dictionary of J. G. von Hahn I am also bringing in photocopies the words ναζαν (nxan), ναζιν (nxin) and vjoči (njun). 9

I am talking about the previously mentioned information of J. G. von Hahn, that it is not completely correct, because we find this sound not only among the Gheks, but also among the Arbëresh in Greece and Italy, and even written with the same letter, namely the letter (n) in the Greek-Albanian dictionary of Panayiotis Koupitoris from Hydra and among the Arbëresh of Sicily written И.

From the dictionary of P. Koupitoris I have taken the words written with this letter: tosóv (çon), gέn (gen), ζgερόν (zgeron), gjoúav (gjuan), ντζείν (nxein).10 From the Arbëresh of Sicily, I present the following icon, where, as can be seen, the letter u is in the name ST. CLAUDIA which is written for the Saint illustrated in this icon, which in the second icon also from Italy is written ST. CLAUDA.

Names that have as their first components KLAM and CLAU, both of which in the Arbëresh language mean: he was knowledgeable. Knowing that KLAM (KLAN) DIA and CLAU DIA, according to the translation, mean “he was knowledgeable”, we can understand why in the third of the following icons ST. CLAUDIA intentionally holds the open book in her hand.

Milos alphabet

Icon of Saint Claudia, of the Catholic Church.

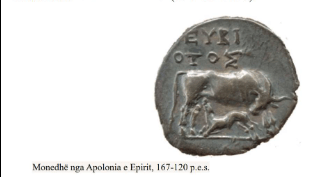

Concluding here my writings on the Milos alphabet, considering that in the above inscription one of its letters is also R, I can completely say that this letter is found in many of the Doric alphabets, of which, according to another coin, is the alphabet of Apollonia in Epirus, in which, as we see, the name or characterization ΕΥΚΙ ΟΤΟΣ (ΕY RI OTOS) is also written in the Doric alphabet.

Coin from Apollonia of Epirus, 167-120 BC.

Returning to the text of the inscription, I repeat it here written in one line, then also giving it transcribed in the Albanian alphabet.

ΔΑΜ ΑTC RAT EMM RIA IC

DHAM ATËS RAT EMN RIA IS

Without going into detail here, we find information about Aty in Dionysius of Halicarnassus, which I quote below:

“from Zeus and the Earth Mother was born the first king of this land. From him and Callirroe, the daughter of Oceanus, was born Cotys, and Cotys, marrying the daughter of Tyllus the native Alie, the two brought forth the children Asia and Aty, while Aty from Kallithea, the daughter of Horaeus, brought forth Lydho and Tyrreno. And Lydho remained with him and after taking power from his father, the country was called Lydia, while Tyrtinnoi, after conquering a large part of Italy with the colonists they brought with the fleet, established his name.”

According to the text of the inscription above, we can say that this inscription is dedicated to RIA IS, and in other words, to what is called the New Isis by the Greeks, who in many ancient representations we find illustrated also as a crescent, as in the coin from Milo that I gave above, with the name written AΛICN, as well as in the other coin, where the name WAAI is written for her. These names which, dividing both into the components NA AICN (NJA LISN) and WAAI (NJA LI), will mean “the first was left”.

Coin of Milo, 5th century BC.

With the appearance called in the above inscription RIA IC (RIA IS) and Nea Isis by the Greeks, I am also bringing the other appearance in the mirror from the ancient city of Praeneste, which I consider to be an Albanian city in Lazio, where, as we see, the name 101515 is written for it, and with the division into the components | DIS IS (I RIS IS).

Bronze mirror from Praeneste, 3rd century BC. National Museum of Palestrina, formerly Villa Giulia. Bibliography: (LIMC, v. III (1), p. 164). E. Gerhard, Etruscan Mirrors IV Taf. 378.

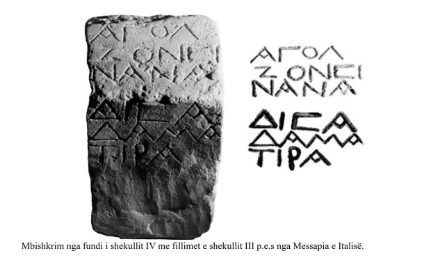

In seeking more information about the above inscription, I am also attaching another one, which was sent to me from Italy by my friends Oreste Caroppo and Elis Duka, which was found in Messapi, Italy and, according to paleographic criteria, dates back to between the 4th and 3rd centuries BC, which I repeat next to it, also written clearly.

Inscription from the late 4th century to the early 3rd century BC from Messapia, Italy.

Before continuing with the writings about its text, I also want to make some clarifications about the letters of the alphabet in which it is written. Starting with the letter, which in many of the ancient Greek alphabets we also find written as F, also known as digamma, the pronunciation of which, although this letter is found in many ancient Greek texts, is unknown or the Greeks do not want to know; I will only say that it is pronounced dij or di written in Frank Bardhi’s alphabet¹2, where ij is found written as a letter, the letter ÿ, as for example in the word Perendij. As a written letter DJ, to date I have only found it in Illyrian alphabets with Latin letters.

Because my writings in Greece, according to the previous characterization of the former rector of the University of Athens, Georgios Babiniotis, are considered without logical basis, for Greeks who do not think “logically”, I am also bringing further reflections of the goddess Athena, known by the Greeks as Athena and by the Romans as Minerva, from the Etruscan mirror, where, as we see, the names MENEDCA – MENEPFA, MENDEA-MENDEA and MENADFA as well as NENADE are written for her.

Name or names that we can say are composed of MENED (NJENER) and CA or FA (DIJA), or NEND (NJENR) and [A or ή ΡΑ (DIJA), as well as MENAD (NJENAR) and (DIJA), but also END (NJENAR) or EN (NJENA) and (REA), which in the Arbëresh language would mean: the first of the second and the first of the new.

Names that we can also call synonyms, because when it comes to two people, the second is also the younger, and the opposite is the younger and the second, and a name or names according to which we can say that the Athena of the Greeks and the Minerva of the Romans was the second who was called ONE or the first or A, with the first called by the millionsWAAI. (NJALI).

Athena in Etruscan mirror representations

Staying on the written record, considering that the above inscription has, like the inscription from Milo, six lines, with half a dozen other words, with four letters written on each line, with the exception of the second line, in which we have five, with the word written ZONCI, believing that the texts in these inscriptions were not written by people with limited knowledge, and assuming that here too we have four letters, I come to the conclusion that one of the letters in this word, and specifically NC, is written with two elements.

Knowing also that in the 4th and 3rd centuries BC, when this inscription was built, the letter NN (NJ) had ceased to be used in the Greek alphabet, I suppose that in the Messapian alphabet it was replaced by Ne, which by a strange coincidence in the Italian alphabet we find written GN. Considering that the letter NE is equivalent to the Albanian NJ, transcribing the word with the Albanian alphabet, we have ZONJI, which is a pure Albanian word.

I find it interesting that in many alphabets of the Albanian language for writing the second letter S, which in today’s official Albanian alphabet is written SH, SC is used, one of which is the alphabet of P. Francesco Rossi da Montalto, which is also written “Il Vangelo di S. Matteo tradotto dalla volgata nel dialetto albanese Ghego Scutarino”, which was published in London in 1870.

Returning to the text of the inscription, I repeat it here written in one line, underlining it and transcribed in today’s Albanian alphabet.

AGOLS ZONCI NANA DICA A TIPA

AGOL ZONJI IN THE HANDS OF THE DHIDIJA.

A text that we can say is dedicated to the mother of AAMA (DHAMA), called in translation into Greek Δώτιδα (Dhotidha), for whom, apart from the fact that the Messapians called her ΑΓΟΛ, we also have information that she was the wife of NANA, with whom she even had a daughter DAMA. Regarding the Doric name DHAMA, I will simply say here that it is the past participle of the irregular verb jap (I gave, gave), which in ancient Greek is called δίδωμι and in modern Greek δίδω and δίνω.

If you don’t know anything about the name ΑΓΟΛ, I’m also bringing another ancient coin of the Kushan empire in Central Asia, where, as we see, the person depicted here with a halo around his head, and in other words as the Sun king, has the name NANA written on it.

Coin of the Kushan Empire of the 2nd century AD.

We find information about this king in Dionysius of Halicarnassus, which he transmits as it is written:

“Knowing from the writings of historians that with what is called the northern landing of the Dorians in Milo around 1000 BC, the Dorians settled, who belonged to the same ethnic group as those who settled in Sparta, but who remained independent, and also knowing from history that the Dorians are identified with the Heraclids, and in other words with the descendants of Hercules, I am simply saying here that one of the names of this Hercules was also Illyrian, who for me is also the national leader of the Illyrians. A topic that we will deal with more extensively in a future article.”

Taking into account what is written about the origin of the Messapians, that most historians claim that they were Illyrian Japigs, who in the 10th century BC crossed the Adriatic Sea and settled in Apulia in southern Italy, taking into account the name AAMA (∆HAMA), which is written in the inscription above, I am also presenting the following coin from the city of Damastion, known from the writings of Strabo as an Illyrian city, where here too, as we see, it is written, and even with a woman depicted on the other side, which we can say that hypothetically it should be what the Illyrians call AAMA, which in the Cham dialect they also call JAPIA. A name from which I assume that the ethnic name Japije is also derived, to whom the Messapians also belonged.

Tetradrachm from Damasition of Illyria, dated 360-345 BC.

Considering the Doric language, and not a dialect as the Greeks say, as a sister language of Illyrian, from Doric Dyrrachium in Illyria, which the Romans renamed Dyrrachion, I am bringing the following coin, where the name AAMA (DHAMA) is written on this one and even with the addition of the word EOZ. This name or description that is written together AAMA ΓΕΟΣ in the Doric dialect of Dyrrachium means: Dhana or Japia Deu (Earth). This name that we can also take as a synonym of DE AO (DHE LOI), which is written for the figure of the Sphinx on the coin from Delphi, I am giving below.

A. Silver drachma from Dyrrachium, dated after 229 BC. B. 5th century BC coin from Delphi.

Knowing that Epidamni was a Doric colony in Illyria, and that the Pelasgian name Epidamni is the equivalent of the Greek Poseidon, writing ΔΑΜΑ ΓΕΟΣ, which is written on the coin above from Epidamni, with a different word order we have ΓΕΟΣ ΔΑΜΑ, and by replacing the Doric E with the Illyrian DHEU, we have ΔΕΟΥ AAMA, and transcribed DHEU DHAMA, which we can also identify with the name Δευάδαι (Dheuadhai), which we find in Hesychius, which is one of the rare Illyrian names that we find in Greek texts.

Considering Strabo’s writings that Damastion was located in Illyria, I am also bringing the other coin from this Illyrian city, where the name AAMA is also written there and even with the additional word NON. Knowing that AAMA NƠN (DHAMA NUN) in the Doric dialect of Damast means “Given mind”, I am also bringing the other coins from Epidamnus, where also there and again with the Greek alphabet the text AAMH NOE (DHAMË NOS) is written, which in the Doric dialect also means “Given mind”.

A. Silver tetradrachm from Damastia, circa 360-345 BC. B΄. Silver drachm from Durrës, dated after 229 BC.

Identifying the so-called AAMA NON on the above coins with ΔΑΜΗ ΝΟΣ, as well as with RIA 1C (RIA IS) named in the Milos inscription and IDISIS (I RIS IS) in the representation of the mirror from Praenesto, with the New Isis called by the Greeks, I translate it for Isis and the other information we find in Plutarch, “her name, it seems, expresses what suits her most of all, knowledge and science”16.

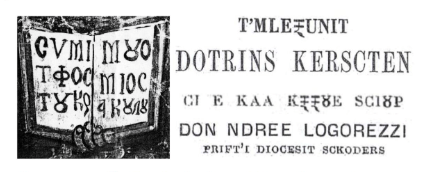

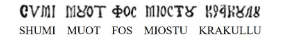

Although I do not want to go into great detail, considering that in the word NON (NUN), which was written in the 4th century BC by the Illyrians of Damastion, instead of the letter OY (U) there is 8, which is not a letter of the old Attic Greek alphabet, I also present the other Albanian text, which was on an icon in the church of Saint Mary of Lumbova in Gjirokastër, which is estimated to have been written in the 6th century, where in this one too, as we see, we have the letter ४. We also have the written letter 8 in the photocopy that I provide below next to the cover of the book by Don Ndree Logorezzi¹¹, who was a priest in the church of Shkodra, which was published in the Vatican in 1880 in the Vatican propaganda printing house, where, even in this, as well as in the text of the icon in the church of Saint Mary of Lumbova, we also have a second U written V and U.

From the text above, which is even written in the Albanian dialect that I also speak, and which is repeated here with word divisions, then also given transcribed in today’s official Albanian alphabet

SHUMI MUOT FOS MIOSTU KRAKULLU

we can say that the letter & is used to write a short U, and V to write a long U, considering that the word CVMI (SHUMI) in the Albanian-German Dictionary of J. G. von Hahn is written as shūmë (shūmë), that is, with a long U.

Approaching the end of my writings, I am translating another quote from the book “Registration of Archaic and Classical Cities” by Mogens Herman:

“As a long-distance trading community, Aegina was not an active colonizer, but colonized Cydonia (no. 968) in 519, Adria (no. 75) around 61, and Damastion in Illyria after 431 (Strabo 8.6.16).”

The fragment where we also have the information that Aegina colonized Damastion in Illyria in 431 BC. Information that, although in the literature that it gives in the edition of Strabo’s Geographical work that I have does not exist, taking it as accurate, I find it very interesting.

Also knowing that with the beginning of the Peloponnesian War in 431 BC most of the inhabitants who were expelled from the island of Aegina and replaced with colonists from Attica, because Athens was worried that Aegina might be able to support the Spartans, I will simply say that, in my opinion, Damastion was not colonized by Aegina, but the persecuted Dorians of Aegina migrated to Illyricum Damastion.

This assumption, if correct, can also be taken as a confirmation of the closeness between the Dorians and the Illyrians, and going even deeper into antiquity, we can also look for the connection of the ancient European civilization in the territory of Illyria with the Cycladic civilization and in general with the Aegean civilization, since from the archaeological findings, of which the following two are also present, we can say that there are elements that support the closeness of these two great ancient civilizations.

A. Goddess on the throne. Green terracotta figure, found in excavations in 1955 on the outskirts of Prishtina. Dates before 3500 BC and according to others in the period 5700-4500 BC. Located in the Prishtina Museum. B. Marble statue of a seated male form holding a musical instrument, lyre or harp. Found on the island of Syros. Dates from 2800 – 2300 BC and is located in the Cyclades Museum.

Although we do not find any written information about the proximity of the Illyrians to the Dorians, and more precisely of the Illyrian language to the Doric language, anywhere, taking into account the question that Oreste Caroppo asked me: “it is said that for the alphabet that the Messapians used, they possibly took it from the Dorian colonies of Taranto. But their language was not Greek”, I want to clarify here that what the Greeks write about the ancient Greek languages, which they call dialects, one of which is Doric, is not accurate.

Discussion

From ancient writings that I believe have escaped the eye of censorship, I also transmit other information that we find in the Marciana commentaries, of the most ancient Greek grammar, which has been partially preserved, of the grammar of Dionysius of Thrace:

“And simply speaking, the dialects are five: Ias (Ionian), Atthis (Attica), Dhoris (Dhoris), Aiolis/Eolis, Koini (united) and the many dialects (languages). Some say that it should not be called Koini (being-united), but mixed because Koini/united is made from the other four, while from four united medicines we do not say common but mixed. And they said correctly about those who support that Koini/united consists of the other four, and for 19 more that the mother of dialects is Koini/united”

Regarding the terms dialect and language mentioned above, I will clarify that the term dialect has the current meaning of language, as well as the opposite, that is, the term language has the current meaning of dialect, and to prove this I also provide the explanatory fragment found on the previous page of the same book:

“We must recognize that dialect differs from language, because dialect contains languages [and history]. The Dhoris (Dhoric) dialect is one, in which many languages are included, (the language of) the Argives, the Laconians, the Syracusans, the Messenians, the Corinthians, and the Aeolian/Aeolian one, in which many languages are also included, (the language of) the Boeotians, the Lesbians, and others”

Knowing that the Greeks do not accept any discussion on this issue, and although they find inscriptions in Greek space that they admit they cannot read, I am also bringing the other fragment from Xanthos of Lydia, as we find it quoted by Dionysius of Halicarnassus:

“From Lidoi they become Lydians, from Torhevi they become Torhevars. Their language deviates a little, and now they use quite a few common words, just as we do with our hands.”

The text in which we can say that we have the information that the Ionians and the Dorians did not have the same language, but they had quite a few, and in other words, many, words in common.

Although I suppose these are sufficient, I am also passing over the other relevant fragment about our language and its dialects from Herodotus, assuming that the accuracy of what is written in it will be more difficult for the Greeks to challenge.

“The Ionians do not all speak the same language, but have four dialects. Their first city in the south is Miletus, followed by Myus and Priene. These two are cities of Caria and have the Ionian dialect. The following cities are in Lydia: Ephesus, Colophon, Lebedus, Theo, Clazomene, and Phocaea. These cities speak the same language, which has nothing in common with the language of the other three. There are three other Ionian cities, two of which are on islands, in Samos and Chios, and the other on the mainland coast and is called Eritrea. The inhabitants of Chios and Eritrea speak the same language, while the inhabitants of Samos have their own language. Thus the dialects become four.”

Commentary and interesting aspects

The fact that Greeks themselves retained several “Illyrian” characters in early local alphabets (e.g. Corinth, Crete, Thera) makes the claim of an Illyrian writing system more plausible.

There is a growing body of research on Albanian as a possible heir to Paleo-Balkan languages, making any comparisons between Messapian, Illyrian, and Albanian relevant – albeit controversial.

Many “illegible” inscriptions in the Aegean consist of mixed alphabets—not because the language is unknown, but because scribes in 600–400 BC experimented with local variants. This may support the idea of a non-standardized, multi-ethnic writing society.

Footnotes

Exhibition catalogue, The History of Writing throughout the World”, University of Athens 2002. p. 52.

The letters T in the Elbasan alphabet table in the book Albanian Studies, Volume I by Johann Georg von Hahn, page 280.

Niko Stylos “Danil Voskopojari’s Quadrilingual Dictionary”, Kristal Publications, Tirana 2011, p. 28.

Liselotte Hansmann and Kriss Rettebech, AMULET and TALISMAN, Publisher: Georg D. W. Callwey, Munich. 1966, f. 156.

Clement of Alexandria, Stromateis, Books IV and V, Pyrinos Kosmos, Athens, 1995, Book V, VI.

σάτε-α (shatë-a), pl. σάτα-τε (shata-të), Karst, Egge. σατόιγ (shatoj), ich hacke Erde. J. G. von Hahn, Albanian Studies, Volume III. (Albanian-German Dictionary).

Panagiotou D. Koupitoris, Albanian Studies, Historical and Philological Treatise on the Language and Nation of the Albanians. Athens, from the Printing House of the Future, 1879. §-98.

J. G. von Hahn, Albanian Studies, Volume II. (Grammar), p. 4).

Ibid. Volume III. (Albanian-German Dictionary).

Niko Stylos, Panajot Kupitori’s Greek-Albanian Dictionary, Apirotan Publications, Tirana 2011.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Archaeology. Verlag B. G. Teubner, Stuttgart, 1967, Book I, XXVII.

Dictionarium Latino Epiroticum, per R.D. Franciscum Blanchum, Romae: Typis Sac.Congr. de Propag. Fide. 1635.

Carl Faulmann, Das Buch der Schrift, haltend die Schriftzeichen und Alphabete aller Zeiten und aller Völker des Erdkreises. Ëien, 1880. Druck und Verlag der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Hof- und Staatsdruckerei. F. 190.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Archaeology. As above. Book I, XXVIII.

1″for above Epidamnon and Apollo as far as the Ceraunian Mountains dwell the Byllions, Taulantes, Parthines, and Brygians. Near these are also the silver mines of Damascus, around which the Dyestes and Angeles (who are also called Caesareti) established their rule together; and near these peoples are also the Lygists, the region of Deuriop, Tripolica of Pelagonia, the Eordae, Elymaea, and Eratria. In ancient times these peoples were ruled separately, each by its own dynasty.” Strabo Geography. Book 7. 7.8.

Plutarch Ethics, On Isidore and Osiris. Book B΄, § – 2.

Don Ndre Logorezzi, T’mledhunit Dotrins Kerscten, Shtypshkornja e propagandës Vatikanit, Rome, 1880. 18 This text is held in his hand by Jesus Christ in an old icon, which was found by the restorer Gazmend Muka during the restoration of the church of St. Mary of Labovo, Gjirokastër, below the newer existing (icon). Since it is written in the Epirote Greek alphabet, Dr. G. Muka, calling it (the text) Greek and not knowing the Greek language, asked for help from his Greek friends, who replied that the text was not Greek. Accepting this answer and assuming that it would be written in a Slavic language, he sent it to Belgrade. There, Ms. Sanja Kesic, from the <<Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments», transcribed it as: ΕΥΜΙ ΤΟ ΦΟΣ ΤΟ ΤΟ Κ(Ο)ΣΜΟΥ ΟΠ(Ο)ΙΟΣ ΑΚΟΥΛΟΥ (ΘΩΝ ΕΜΟΙ) and said that it is a derivative/deviation of «ΕΓΩ ΕΙΜΙ ΦΩΣ ΤΟ ΚΟΣΜΟΥ Ο ΑΚΟΥΛΟΥΘΩΝ ΕΜΟΙ…”. Ms. Kesic’s conclusion is wrong. As evidence of the error, only the letters C and M are sufficient. As we see, C transcribes E the first time and the following two ∑ (S), while M transcribes II the third time. Gazmend Muka, Church of the Nativity of Saint Mary in Labovën e Kryqit, Albas Publishing House, Tirana, 2013, p. 78.

Grammatiki graeci, Georg Holms. Hildeshein publishing house, 1965, f .303.

20 Ibid., f. 302.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Archaeology. As above. Book I, XXVIII.

Herodhoti Alikarnasi Historie, Libri I, 142.

This study and analysis was published by Niko Stylos. Translated and edited by Petrit Latifi.