Background

In the early nineteenth century, the Austrian Empire ruled the Dalmatian coast, including Cattaro (Kotor), Budva, and Castel di Lastua (modern Petrovac). Just inland lay Montenegro, an autonomous mountain principality under Petar II Petrović-Njegoš. The frontier between the two was undefined, mountainous, and volatile. Raids, smuggling, and retaliatory incursions were common, with both sides accusing the other of violating the border.

By mid-1838, tensions flared after Montenegrin bands attacked Austrian outposts and plundered settlements near Lastua. The Austrian response would culminate in one of the most dramatic frontier actions of the pre-1848 period.

The Battle of Kopaz

On 2 August 1838, Montenegrin irregulars—estimated at several thousand from the Czerniczka, Rička, and Katunska regions—descended from the mountains and occupied Mount Kopaz, threatening to advance on Novosello (near the Albanian Bojana river and Castel di Lastua (modern day Petrovac).

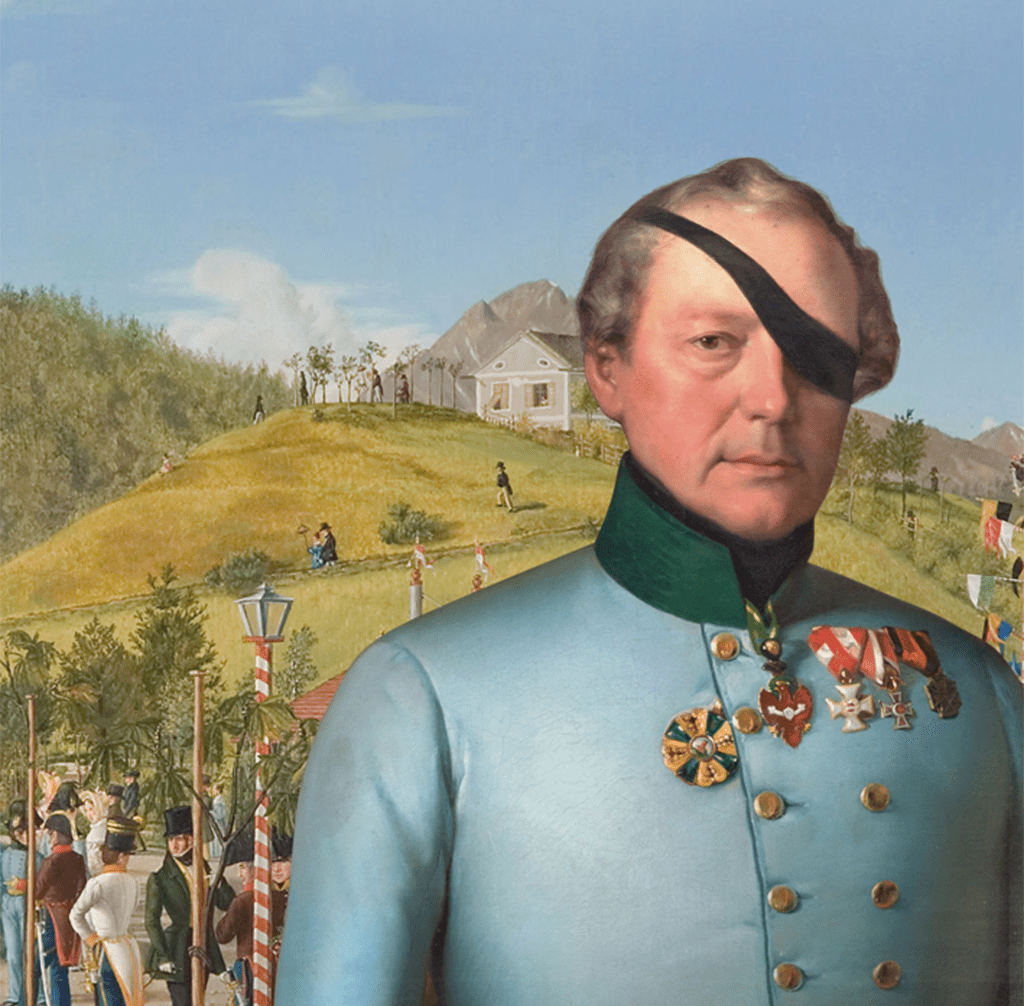

Lieutenant Colonel Baron Friedrich von Roßbach, commanding the 8th Jäger Battalion, led roughly 750 Austrian soldiers—a mix of Jägers (light infantry), regular infantry, and locally raised Pandurs and Terriers. Despite exhaustion from a forced march, Roßbach resolved to storm the heights immediately.

Under intense fire and heavy stone-throwing from the slopes, his five Jäger companies advanced in tight formations and retook Kopaz after a sharp uphill fight. According to Austrian reports, hundreds of Montenegrins fled, while Austrian losses were minimal. The victory restored order and lifted morale among the local Dalmatian population, who had fled the fighting.

Escalation and wider operations

Skirmishes continued for several days around Gomila, Vidrak, and Oggradenizza, with Montenegrin forces counterattacking under Georg Petrovich. On 5–6 August, Roßbach planned a wider repressalie (reprisal operation) into the Planina Paštrovičiana, a highland zone regarded by the Montenegrins as private tribal land.

Despite diplomatic efforts by Montenegrin envoys to avoid open war, intelligence reached Roßbach that additional enemy contingents—supplied with ammunition by the Vladika (Njegoš) himself—were massing to strike first. Determined not to be pre-empted, Roßbach launched a coordinated attack at daybreak on 6 August, deploying six assault columns in a semicircle.

The Austrian force was small—barely 1,450 men including irregular auxiliaries—against over 5,000 Montenegrins who enjoyed strong defensive positions and a reserve of 3,000 near Gliundo and Cettinje. Nevertheless, after hours of intense fighting under severe heat and water shortage, the Austrians succeeded in burning and destroying Montenegrin stockpiles and homesteads, fulfilling the objective of the reprisal.

Austrian losses were heavy for such a small action: 19 dead (13 Jägers, 3 infantrymen, 3 Pandurs) and 20 wounded, including several officers and the bairaktar (standard-bearer). Montenegrin casualties were estimated at around 50 killed or wounded.

Outcome

By nightfall on 6 August, fighting subsided, and Roßbach consolidated his line at Kopaz. The following day, a message arrived from Brigadier General Ritter von Tursky, informing him that negotiations had begun: the Vladika of Montenegro had ordered his men to withdraw from the Paštrovići region and to suspend hostilities. Roßbach immediately ceased fire across the line.

Although minor in scale, the campaign had an outsized effect. In Austrian military circles, Roßbach’s action was hailed as proof that a handful of disciplined troops could dominate and overawe irregular mountain forces, and that “the hiding places of the Montenegrins were not beyond reach.”

Roßbach’s leadership and the courage of his Jägers were formally recognized, and he was later commended in the records of the Military Order of Maria Theresa. The engagement reinforced Austrian control along the Dalmatian frontier and temporarily discouraged Montenegrin raids.

For Montenegro, the event underscored both the limits of its power and the fragile nature of its relations with the neighboring empire—a foretaste of the tense Austro-Montenegrin interactions that would continue throughout the nineteenth century.

It is also interesting to note that Castel di Lastua, re-named later to Petrovac, is mentioned to be close to the Turko-Albanian border. From the publication:

“Outnumbered and disadvantaged by the terrain, the surveyors and seasoned riflemen of the 8th Battalion disarmed the enemy and, as their only desperate means, launched an assault on our rifle post. At the same time, the Vidrak post was attacked in the area stretching from Castel di Lastua to the Turko-Albanian border. Only with difficulty could Novosello be saved from the plundering and savage fury of the Montenegrins.”

Source

Militär-Zeitung Volume 11. 1858. https://www.google.se/books/edition/Milit%C3%A4r_Zeitung/vcdFAAAAcAAJhl=sv&gbpv=1&dq=Montenegro+novosello&pg=PA303&printsec=frontcover