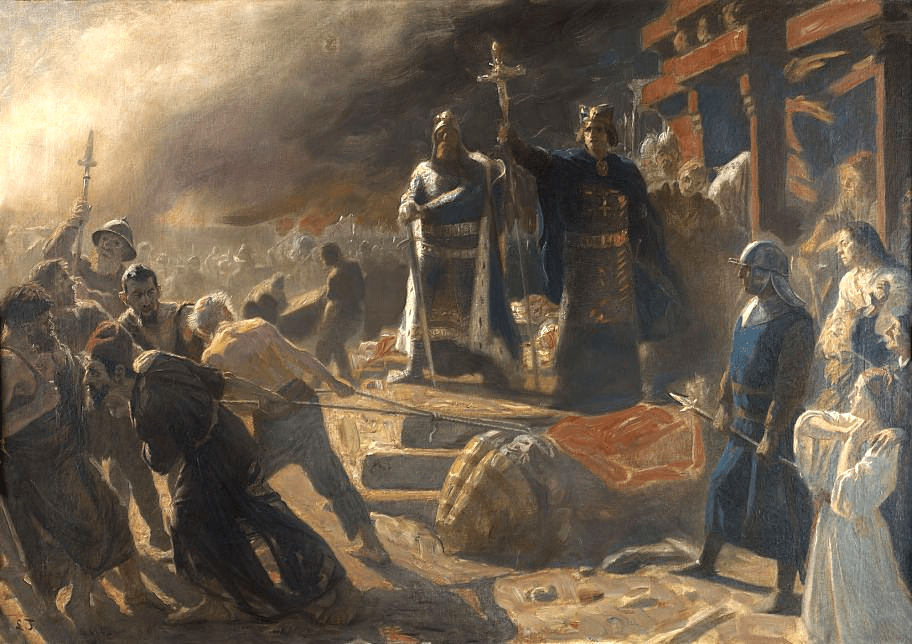

Image taken from https://www.worldhistory.org/.

Abstract:

This study reassesses the chronology, character, and mechanisms of early Slavic settlement in the Balkans based on recent historiographical and archaeological interpretations. Contrary to traditional narratives that place a large-scale Slavic “invasion” in the 7th century, the evidence presented here suggests a more gradual, irregular, and prolonged infiltration beginning in the mid-6th century.

Contemporary Byzantine sources, such as Procopius and the Strategikon, describe Slavic and Antes groups as mobile, loosely organized communities lacking fixed territorial structures. Their early presence south of the Danube appears episodic, consisting largely of raiding groups rather than permanent settlers.

Only between 587 and the mid-8th century did more stable Slavic communities emerge in parts of the Balkans. Modern scholars—including Klaic, Hermann, Birnbaum, and Chrysos—emphasize that Byzantine administrative policies significantly shaped where and how Slavic groups were settled, integrating them into imperial frameworks rather than losing territorial control. The paper therefore rejects simplified invasion models and highlights the complexity of Slavic ethnogenesis, migration routes, and interactions with indigenous Balkan populations.

Skender Gashi writes:

How accurate is it that Slavic tribes invaded the Balkans in the 7th century?

What do the latest scientific data show about their arrival in the Balkans?

How much influence did the Byzantine Empire have in determining the lands where the Slavs would settle?

The 7th century AD is never directly or indirectly mentioned.

And this would almost certainly be considered the earliest date of the Slavs’ presence in the Balkans, including in areas inhabited by Albanians. This same position is also evident when reading different versions of the history of Albania or Kosovo and other areas inhabited by Albanians. It should be borne in mind that their appearance since the 7th century, initially in hordes or in groups of robbers, does not mean their permanent settlement in those areas.

Until now, it has been It is believed that the Slavs began to settle in the Balkan Peninsula during the reign of Emperor Justinian (627-565) and for a short time, within the two decades that followed, they had conquered most of this peninsula.

Historiographers contemporary to Emperor Justinian actually speak of two larger groups of Slavs, namely the Greek Sklavoi, the Latin Sclaveni, Sclavi and the Latin Antes for the Anatal

Historiographer Procopius, a contemporary of Justinian from Caesarea in Palestine, shows at that time that these two populations spoke the same language and were similar in physical appearance.

Half a century later, in the book Strategikon – which is considered to be the work of Emperor Maurice (582-602) – Procopius’s statement is repeated and added that The Slavs and the Antes also had similar lifestyles.

While the ethnic identity of the Slavs remains undisputed, the commonality of the members who, together with the Slavs and mixed with them, came to the Balkans is thought to be a Slavicized Iranian-Sarman tribe.

Although the frequent attacks of the Slavs located above the Danube-Sava line, which at that time constituted the border of the Byzantine Empire, had occurred before, a serious attempt to settle the Slavs within the territory of the Byzantine Empire can be said to have occurred after the year 550, when their attacks became much more frequent.

This becomes clear also in the light of the circumstances of Procopius, as well as other sources, which report Slavic attacks that occurred almost every year.

In the writings of Procopius, several Slavic toponyms are also mentioned in the valleys of the Morava and Timok rivers, which proves that Slavic groups had occupied places in those regions since ancient times. In addition, contemporary historians have learned that in the army of Justinian, who was fighting in Italy at that time, there were also Serbian soldiers.

This means that mobile groups of Slavs, who had crossed the border of Byzantium, had penetrated into the depths of this empire since the sixties of the 6th century. However, the Slavs did not have permanent settlements at that time and this presence should not be understood as an invasion or as their actual settlement in the Balkans.

The opinion of the Croatian historian, N. Klaic, and the German archaeologist J. Hermann, quoted by Henrik Birnbaum, Von Ethnolinguischer Einheit zur Vielfalt Die Slaven im Zuge der Landnahme der Balkanhalbinsel, Sudost-Forschungen, seems to be sufficient. Bd 51,1992 p. 9 that the waves of Slavic invasion in the Balkans should no longer be taken as a major event with major consequences, but that their arrival in these regions should be understood more as an infiltration and as a gradual internal movement, then to some extent as a penetration of the Slavic element, which initially appeared in small and isolated groups.

In addition, it should be accepted that these Slavic groups, initially separate, acquired their ethnolinguistic identity and a kind of ethnic consciousness only as a result of the pressure exerted on them by the Slavs. There is no reason, therefore, for the Slavic tribal groups, before they fell into symbiosis with the Avars, to be considered as some large ethnic unit.

Since this work does not pretend to be any contribution to Slavic studies, we will let us limit ourselves only to the manner and time of the settlement of the Slavs in the Balkans and more precisely in Dardania.

However, as for general knowledge, it should be noted that the real settlement and establishment of the Slavs in the south of the Balkans, namely in the Peloponnese and on the Adriatic coast, occurred from 587-746 – when their settlement also took place up to the line formed by the Elbe-Saale rivers and even to the Main in Germany.

For the sake of completeness, it should also be said that it remains to be seen whether the northern region of the Korpati – approximately the area between the Tatra Mountains and up to Bukovina – or some other region should be accepted as the original homeland, namely the area of Slavic ethno-glottogenesis after the departure from which later, under different geomorphological conditions, the differentiation and assimilation of the South Slavic languages followed.

The date of Slavic migrations also remains debatable: did the Slavs spread from the Carpathians first to the Balkans and then to Central Europe and even to Baltic or would the opposite have happened.

While we are talking about the pre-Balkan Slavs, it is worth mentioning the opinion of J.Hermann cit.

According to Henrik Birnbaum, Von Ethnolinguisticher Einheit zur Vielfaltie Slaven im Zug eder Landnahme der Balkanhalbinsel, Sudost-Forshungen, Bd.51, 1992 p.9) according to which “it is likely (…) that from the tribe of Serbs-Sorbians, which in the 6th century was settled in the middle course of the Danube on the borders of Byzantium and which had to confront the Avars, a part of that tribe broke away and migrated northwards.

It seems that this migration to the North was joined by several groups from the tribe of Croats, which together with the Serbs, operated in the middle course of the Danube, as well as some Bulgarian tribes. Returning to the borders of Byzantium in the 6th century in relation to the migration of Slavs to the Balkans and Western Europe, the Serbian scholar, Pave Ivic, has expressed the opinion that while a part of the eastern tribes of the southern Slavs lived in the plains of the Dacians, their western group would have lived earlier in the Pannonian Plain, in today’s Hungary, separated from the other eastern tribes by the Carpathians.

“On the other hand, the mountain tribes themselves were not inhabited by Slavs, but by a proto-Romanian (so-called Vlach) and Albanian population, populations that were accustomed to a transhumance way of life” (cited, according to Henerik Birnbautn, poaty, p.7).

In any case, the appearance of Slavic groups in the Balkans, especially in the 7th and 8th centuries, over large territories (although the manner and extent of the penetration, at least in the first phase of the influx of peoples, must be further investigated) should not be seen as a complete and genuine invasion, because during that time the Slavs – in alliance with the Avars and partly with the proto-Bulgarians and the Germanic tribes of the Gepids, they did not have the strength to attack Byzantium.

Therefore, it is not correct to think that before the 8th century large territories of Byzantium – with the exception of Thessaloniki – could have been inhabited in a constant and homogeneous manner by any Slavic-speaking peoples, says Birbaum (ibid., p. 9). A separate question is how the Slavs, more precisely the South Slavs, managed to establish themselves in today’s Bulgaria, in the former Yugoslavia, in parts of Greece and Albania.

The most acceptable answer to this was given, according to Birnbaum (ibid., p. 10), by E. Chrysos in an unpublished lecture, held in Münster, Germany. “The imperial government of Byzantium participated much more than is thought and how can be evidenced in written sources in the settlement and determination of the territories in which the Slavs would be settled (…)

All indications lead us to a vague conclusion that the settlement of the Slavs in the territory of the empire and their rapid integration was done within the framework of the previously defined concept of the imperial government. The sovereignty of the Byzantine Empire was not seriously questioned either in that transitional period or later, neither in the legal nor the political aspect,” he continues.