by Prof. Dr. Sylë Ukshini. Translation Petrit Latifi

Abstract

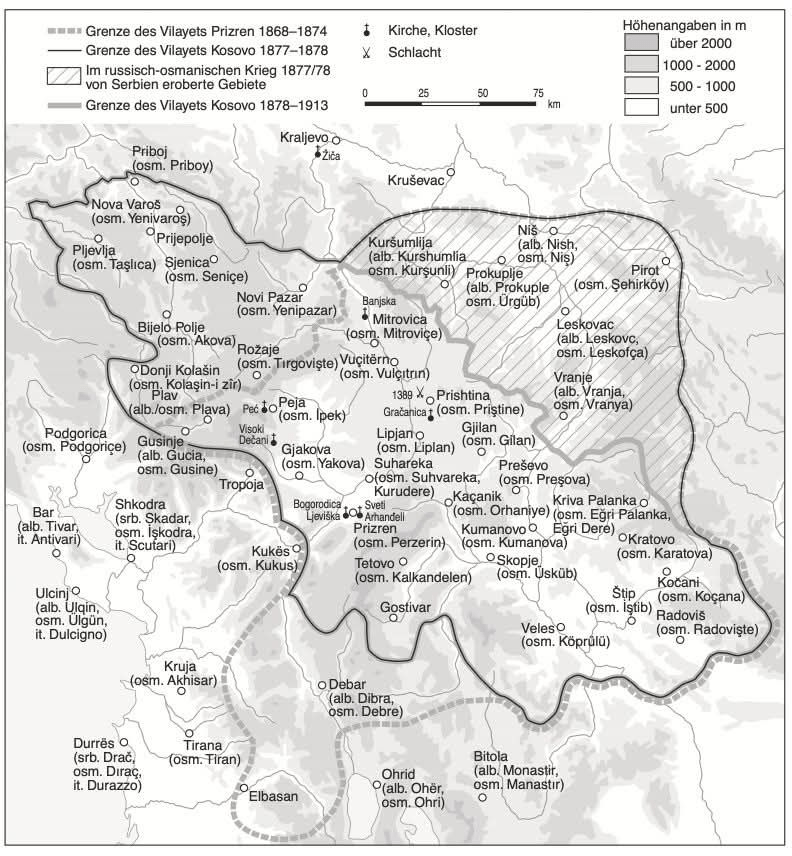

This article examines Russian–Serbian cooperation in the northern districts of the Kosovo Vilayet at the beginning of the twentieth century, focusing on a confidential Austro-Hungarian consular report written in Skopje on 6 August 1901 by Consul Gottlieb Pára. The report provides detailed evidence of coordinated Russian and Serbian diplomatic, political, and propagandistic activities aimed at destabilizing Ottoman Kosovo and countering Austro-Hungarian influence. It documents the arming of Serbian villagers, the exaggeration of refugee movements, and the deliberate circulation of misinformation regarding the origin of weapons, as well as Russian interventions within the Ottoman administrative hierarchy. Particular attention is given to the role of Russian consul Mashkov, Serbian local agents, and pro-Serbian journalists in shaping international perceptions. By situating these actions within broader Great Power rivalries, the article demonstrates the structural continuity of Russian–Serbian policies toward Kosovo and highlights the deep historical roots of contemporary regional tensions.

Russo-Serbian Pan-Slavist plans for Albanian territories

In the Austro-Hungarian consular reports of the early 20th century, the cooperation between Russian and Serbian diplomats in the north of the Kosovo Vilayet (Üsküb/Shkup) is presented as a stable element of geopolitical rivalry in the Balkans, as well as permanent Serbian efforts to destabilize Kosovo through the arming of the population and Serbian gangs.

A timely and significant piece of evidence in this regard is the report of the Austro-Hungarian consul Gottlieb Pára, addressed to the Foreign Minister Alois Lexa von Gołuchowski, dated August 6, 1901, drafted from Skopje, then the administrative center of the Vilayet.

Reading the secret reports of European diplomats on Upper Albania (Kosovo) reveals obvious parallels with contemporary political developments and with the consistency of Russian policy against Kosovo.

The 1901 report also sheds light on this structural continuity, documenting Russian-Serbian coordination on the ground and the instrumentalization of local issues for strategic purposes.

The article highlights, among other things, the exaggerated presentation of the displacement of Serbian families from Novi Pazar, the shipments of weapons from Serbia, and the deliberate spread of rumors about the alleged Austro-Hungarian origin of these weapons.

The report also addresses the actions of disarming the population, carried out in part under the leadership of Isa Boletin, as well as the journey of a Czech journalist with a pro-Serbian orientation, who served to reinforce political narratives in favor of Serbia.

Another important aspect is the dissatisfaction of the Ottoman governor with the disarmament of the Serbian population by the mutasarrif of Pristina, as well as the Russian intervention in dismissing this official. Pára also notes signs of disloyalty within the Ottoman administration, plans to convene an Albanian assembly near Peja, and the precarious position of the Serbian vice-consul in Pristina and the Serbian metropolitan in Prizren.

Overall, Pára’s report constitutes an important source for understanding the mechanisms of Russian-Serbian influence in Kosovo at the beginning of the 20th century and proves that the current tensions in the region have deep historical roots, linked to the competition of the Great Powers and the instrumentalization of local Balkan realities.

Consul Para further writes:

“The episode of the turbulent days in Pristina, Mitrovica, Kolasin and Novi Pazar seems to have ended with the return of the military commander Ferik Nuri Pasha, on Saturday the 3rd of this month, as well as with the arrival today of Mr. Mashkov after his three-week excursion. From the observations that these events offered to an impartial observer, it is worth mentioning in the first place the fact that the Russian government once again did not let the opportunity to interfere in the internal affairs of the Ottoman Empire escape, claiming a so-called right of protection over the entire Slavic-Orthodox Christian world.”

On the basis of the notification received from the Serbian vice-consul in Pristina, that the latter – due to the threatening attitude of the Muslim population – had been forced to interrupt without result the journey undertaken on July 15 towards Mitrovica, with the aim of intervening in favor of the Christian population of Kolasin (from which the Muslims had taken up arms), Mr. Mashkov requested from his embassy to send him (command) to the north of the vilayet. This request was immediately accepted and he left on 17 July for Mitrovica, joined by the Serbian vice-consul in Pristina, Avramović.

Mr. Mashkov stayed longer in the area of Kollashin, which lies on both sides of the Ibar River west of Mitrovica and is inhabited mainly by Christians. In the village of Brnjak (about 27 km as the crow flies west of Mitrovica) he is said to have been seriously threatened by the Muslims gathered there, so he had to seek military protection. Mashkov was able to communicate freely with the Orthodox population of that area and to draw up minutes of testimony regarding the oppression and ill-treatment allegedly suffered by the Muslim population.

On 30 July, he arrived in the company of the Russian Guard officer, Rittich, in Novi Pazar, where he settled in the Serbian school and continued his investigations in the same way as in Mitrovica and Kolasin. According to the account of Mr. von Rittich, who returned here on the 3rd of this month, Mashkov managed to discover some traces of mistreatment and torture of Christians by Muslims.

As a particularly serious matter he mentions the fact that, at the time of his arrival in Novi Pazar, the disarmament campaign was still going on, although the imperial decree prohibiting further persecutions against Serbs had been issued as early as July 23.

Although many Christian inhabitants have abandoned their settlements during the last three months and have taken refuge in Serbia, the figures published by the Serbian newspapers on this matter are clearly exaggerated. In the areas visited by Mashkov, according to Rittich himself, the number of those who fled is small and they mainly ht belong to the best classes (e.g. priests, etc.).

According to information received from reliable sources, the Russian representative used his contact with the Christian population to promote a position against Austria-Hungary, especially against the project – which he considers to be decided – for the extension of the Bosnian railways to Mitrovica.

The issue of arming the Christians deserves special interest, which neither the Serbian side nor Mr. Mashkov can deny. Since during the last few weeks several hundred Martini rifles were found in the possession of Serbian villagers in the northern part of the vilayet, the Serbian leaders of the arming campaign and their Russian protectors are now trying to somehow “credibly” explain to the European public opinion the origin of these weapons.

Always capable of invention and distortion, the Serbian and Russian sides comment that the weapons were smuggled in by Albanian smugglers and sold to the Christian population. The Turkish authorities, however, say otherwise, as they have evidence and confessions from many Orthodox – repentant – that the weapons came from Kuršumlje and were distributed free of charge through the mediation of the priest of Kolašin, Mihajlo, who had fled to Serbia the previous year. Moreover, the Serbian version falls flat if we consider that a Martini rifle here still costs 40–50 guilders, an unaffordable sum for the poor Christian border inhabitants.

There is no shortage of rumors spread from Serbia today that the entire movement was staged by Austria in order to finally realize its idea of advancement. It is unfortunate that such insinuations have also found their way into major newspapers such as “Novoje Vremja” and “Národni listy” (the latter, for example, in its issue of July 9 of this year, referring to an article in “Novoje Vremja” based on completely false circumstances, demanded from Your Excellency to immediately withdraw me from the post of consul in Skopje and – as happened once with Mr. von Kuczyński – to send me somewhere to South America).

Symptomatic in relation to recent events was also the visit of the editor of “Novoje Vremja”, Vsevolod Svatkovsky (who uses the pseudonym “Nestor”), accompanied by the aforementioned Guard officer. After several trips from Skopje to the Slavic villages on the slopes of Karadak, as well as to Tetovo, Köprülü, Prilep and Thessaloniki, to collect data on the linguistic and national affiliation of the South Slavs (Serbs and Bulgarians), the two returned to Skopje and on July 22 traveled to Mitrovica to join Consul Mashkov.

Initially, they intended to go as far as Bosnia, but they seem to have abandoned this plan due to the possibility of quarantine at the border. Svatkovsky returned to Skopje on July 23 and on July 28 left for Bulgaria, while von Rittich stayed with Mashkov until August 2. It is easy to understand that the officer will use his military-geographical observations, supplemented by numerous photographs, in an official manner.

I have become more familiar with both gentlemen. Mr. Svatkovsky, referred to me by the Czech deputy Dr. Kramář (whom I do not know personally) was in no hurry to fulfill this “mission”; he came to me only after he had spent several days in intensive communication with the Russian and Serbian consuls.

This talented and relatively cultured journalist appeared to be an ardent propagandist of Pan-Slavic ideas; consequently, he has no sympathy for the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, at least as long as – as he says – the centralist order in Austria is not replaced by a regime that takes into account the interests of the Slavic peoples (i.e., a federal system).

He especially condemns the Monarchy’s policy in the occupied provinces. I replied that, in order to form a more fair judgment on Bosnia-Herzegovina, it would be useful for him to carry out the planned trip, where he could be convinced that the so-called “Catholic propaganda” of the government there is nothing more than a crudely invented fable.

Although Svatkovsky declares that he is impartial in the Macedonian question and would like a Serbian-Bulgarian brotherhood, this “impartiality” disappears whenever a concrete case is discussed regarding the linguistic affiliation of a province, where he regularly appears as a supporter of the Serbs.”

(The text continues with the section on the position of the Ottoman authorities, the role of the mutasarrifi Xhemal Bey, the disarmament action undertaken by the Muslim population under the leadership of Isa Boletini and Adem Çaushi, intrigues within the administration, and the plan for an Albanian meeting near Peja; if you wish, I will immediately translate that section to the end, without abbreviating it.)

Reference

Oliver Jens Schmitt and Eva Anne Frantz (eds.), Politics and Society in the Province of Kosovo and in Serbian-ruled Kosovo 1870–1914. Reports of the Austrian-Hungarian Consuls from the Central Balkans, Volume 4 (1908–1914), Writings on Balkan Research, Wien: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften / Böhlau Verlag, 2020.