Abstract

This study examines historical testimonies concerning the presence and role of Albanian-speaking (Arvanite) populations in Greece from the early modern period to the nineteenth century. Drawing on travel accounts, memoirs, linguistic works, and intellectual writings, it highlights the widespread use of Albanian in islands such as Hydra, Spetses, and Poros, as well as within the Greek fleet. The analysis also explores nineteenth-century theories of a shared Pelasgian origin between Greeks and Albanians, as articulated by figures such as Anastas Byku and referenced in broader Balkan intellectual discourse. These sources reveal a complex linguistic and cultural interdependence that challenges later nationalist narratives of rigid ethnic separation.

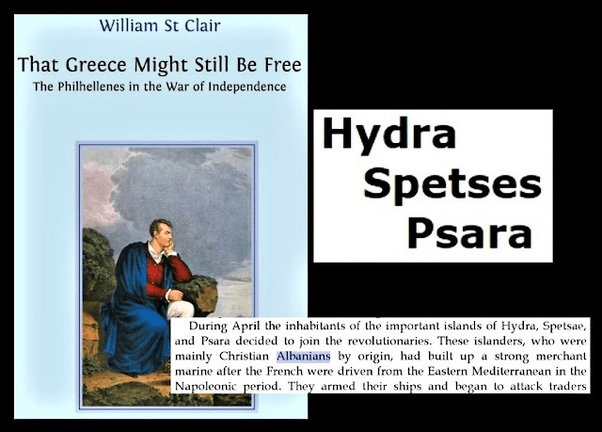

“In Hydra and Spetses, on the other hand, the Greek language was almost unknown to the inhabitants, who spoke Albanian, in contrast to Psara, where it was spoken on the breadbaskets. Krazis reports that as early as 1670, the spread of the Greek language began in Hydra from Peloponnesian refugees who had taken refuge there, while the teacher in Poros, Epiphanios Demetriades, notes in his memoirs that “if you teach Greek, you are the first to teach Albanian.”

“Albanian (Arvanites) sailors of the Greek fleet demand their payments at the port of Poros.”

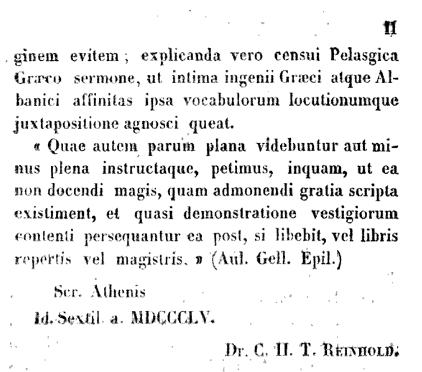

“I will avoid the word “gine”; but I have decided to explain Pelasgian in Greek, so that the intimate affinity of the Greek and Albanian intellects can be recognized by the very juxtaposition of words and expressions.”

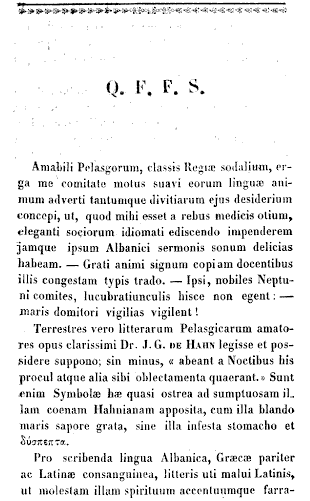

“The amiable Pelasgians, members of the King’s fleet, I was moved by their kindness, and I was attracted by their sweet language, and I conceived such a desire for their riches that, since I had leisure from medical matters, I would spend my time learning the elegant idiom of my companions, and now I delight in the very sound of the Albanian speech. I give a token of my grateful spirit to those who teach me, the noble Neptu-those, accumulated in print. If the companions do not need these little reflections: let them keep vigil for the master of the sea!

I suppose that terrestrial lovers of Pelasgian literature have read and possess the work of the most illustrious Dr. J. G. DE HAHN; if not, “let them go far from these Nights and seek other amusements for themselves. For these Symbols are like oysters placed at the sumptuous il.. lam Hahnian dinner, with that pleasant, bland taste of the sea, without that infesting the stomach and indigestion.

Instead of writing the Albanian language, which is related to both Greek and Latin, I preferred to use Latin letters, so as to avoid that troublesome jumble of spirits and accents.”

“The lovable Pelasgians, the exhausted companions of the King, were so moved by the kindness of their sweet language that I was attracted to their spirit and conceived such a desire for their riches that, while I had leisure from medical matters, I spent it learning the elegant idiom of my companions and now I delight in the very sound of the Albanian speech. I give them a token of my grateful spirit, which I have accumulated in print, to those who teach them. They, the noble companions of Neptune, do not need these little reflections: – let the tamer of the sea keep vigil!

Instead of writing the Albanian language, which is related to both Greek and Latin, I preferred to use Latin letters, so as to avoid that troublesome jumble of spirits and accents; but I decided to explain Pelasgian in the Greek language, so that the intimate affinity of the Greek and Albanian intellects could be recognized by the very juxtaposition of words and expressions.”

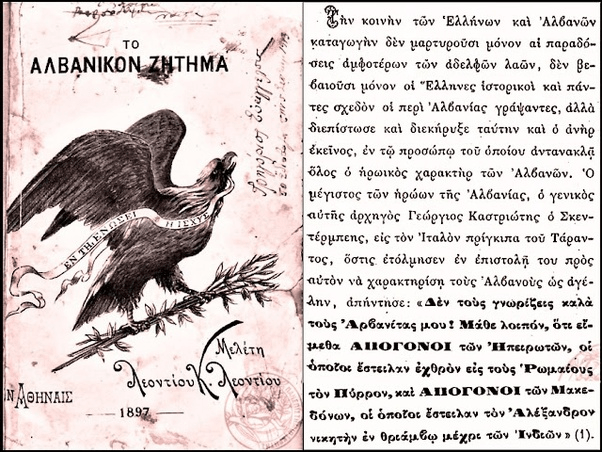

“The common origin of the Greeks and Albanians is not only attested to by the traditions of both brotherly peoples, not only confirmed by Greek historians and almost all those who have written about Albania, but also ascertained and proclaimed by that man, in whose face the entire heroic character of the Albanians is reflected. The greatest of the heroes of Albania, its general leader George Kastriotis Skanderbeg, to the Italian prince of Taranto, who dared in his letter to him to characterize the Albanians as nobles, replied: “You do not know my Albanians well! Know, then, that we are descendants of the Epirotes, who sent Pyrrhus as an enemy to the Romans, and descendats of the Macedonians, who sent Alexander the victorious in triumph as far as India” (1).”

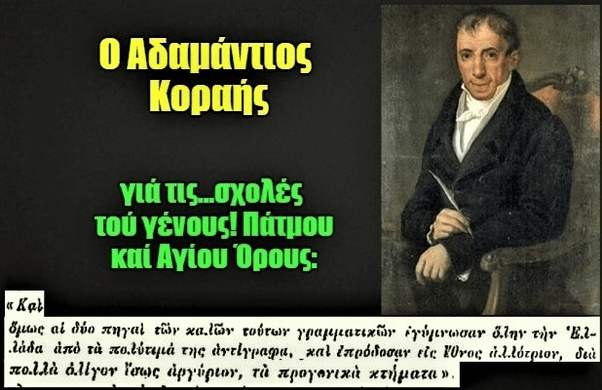

“However, the two sources of these good grammars stripped all of Greece of its precious copies, and betrayed their ancestral lands to a foreign nation, for perhaps very little silver.”

– Adamantios Korais

“He who persecutes the Albanian race cuts the nerves of Hellenism”! “PYRRHUS”, Athens 1905.

Sources

William St Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free, The Philhellenes in the War of Independence.

HISTORY OF THE REEK REVOLUTION, GEORGE FINLAY, LL.D. IN TWO VOLUMES WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS EDINBURGH AND LONDON MDCCCLXI

Anderson, Rufus. Observations Upon the Peloponnesus and Greek Islands, Made in 1829. Boston: Crocker and Brewster, 1830. A traveler’s account noting the prevalence of Albanian language (Arvanitika) on Hydra, Spetses, Poros, etc., and the spread of Greek among refugees and later populations

“Arvanitika.” Overview of the Arvanite dialect (a variety of Albanian) spoken in Hydra/Spetses, its writing systems (Greek/Latin), and historical bilingualism

“Hydra (Island).” Discusses Albanian settlement from the 16th century, Arvanitika usage, and the later shift toward Greek.

“Panayotis Koupitoris.” Biographical article on a Greek-Albanian writer from Hydra who studied Albanian language and published works on Albanian/Greek linguistic connections.

“Anastas Byku.” Lists Byku’s publication of Pelasgos and his ideas about Greek and Albanian shared origins and Pelasgian identity