This article discusses various photographs and reports of Serbian and Yugoslav atrocities and war crimes carried out by Serbs in Albanian territories for the past 150 years. These crimes stretch from 1878 to 1999. The photos and the information is extracted from Fadil Kajtazi’s book “THE SERBIAN IDEOLOGY OF GENOCIDE (Analysis from Serbian and international sources) ENGLISH EDITION” published in 2025. Parts of the book has been translated and edited by publicist Petrit Latifi. This is part 1.

The Genocide Begins – The First Great Expulsion 1877 – 1878

The Congress of Berlin paved the way for the mass murders and expulsion of Albanians from their lands. “At the Congress of Berlin, Disraeli (aka Lord Baconsfield, British Prime Minister, F. K.) and Bismarck had divided the Albanian lands and given them to Serbia and Montenegro. Serbia was given the region of Toplica, while Montenegro was given the city of Podgorica and the port of Tivar, to which a harbor, that of Ulcinj, was added in 1880.

When the Serbs expelled tens of thousands of Albanians from Toplica and Vranje in 1878, to make way for settlers, the British representative in Serbia, Gerald Francis Gould, complained to Lord Salisbury about Serbian brutality. ‘The peaceful and working inhabitants of over 100 Albanian villages in the Toplica Valley and in Vranje were forcibly expelled from their homes by the Serbs in the first part of this year.

These miserable people have been wandering up and down ever since in a state of deep hunger,’ he wrote. Nothing happened to Serbia after these complaints and the Serbs quickly and effectively changed the population structure in that region”.

The ethnic cleansing of this area was planned by the Serbian government and the order was given by Prince Milan Obrenović (1783-1860) himself, which, according to officer Dimitrije Mita Petrović, a direct participant in the events, on 30.11.1877, was read after the Serbian army was gathering to advance towards Albanian lands. On this day, after the Serbian priests blessed the army with holy water, Colonel Lešjanin saluted the army and, among other things, read the order of Prince Milan Obrenović, which stated:

“The fewer Albanians who remain in the territories liberated from Turkey, the more you will contribute to the state. The more Albanians who are displaced, the greater the merits for the homeland”. This is an order for genocide, the effects of which are later explained by Čubrillović, when he states the territorial expansion of the Albanians and compares it to a wedge that stopped the expansion of the Serbs to the south, saying:

“Thanks to the broad state concepts of Jovan Ristić, (Prime Minister, F. K.), Serbia broke another piece of this wedge, after the annexation of Toplica and Kosanica. At this time, the regions between Jastrebac and the southern Morava were radically cleansed of all Albanians”.

Demographics at the time

Due to the circumstances, the source documentation of this tragedy of the Albanian people is scarce, however, sufficient to establish that genocide occurred. Only the order of Prince Obrenović and the statement of academician Čubrillović after 60 years that the order was fully implemented, are evidence of a genocide attempt.

Another issue that remains insufficiently clarified in this process is the number of inhabitants expelled from their properties. From a statement by Čvijić, Serbian science accepts that this number is “around 30,000”, but the cleared territorial area and the ethnic composition of this territory indicate that the number of expelled inhabitants must have been much larger.

We can approximate an overview of the ethnic composition of this area with the city of Kraljevo, which is geographically above the city of Niš, to the northwest. This city, “in 1784 there were 11 Serbian houses and 89 Tutka and Albanian houses. Karanovci (Kraleva as it was called until 1805, F.K), had the following number of inhabitants: 72 Serbs and 592 Turks and Albanians. In 1805, Karanovci was conquered by the Serbs, while the Turks and Albanians were expelled to Novi Pazar”.

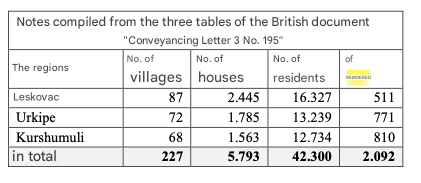

In a letter from representatives of the population of the region of Niš, Leskovac and Prokuplje, sent to the British representative in Belgrade on 2 June 1882, they indicated that they were speaking on behalf of “150,000 unfortunate, ruined and destroyed Muslims”619. Also, from a “Conveyance Letter 3 No. 195” of the British representative in Serbia, in which the number of houses and inhabitants of the Albanian population of these regions are presented in a tabular form for each village, it results that 42,300 inhabitants lived in only 277 villages of the three regions:

The entire deportation process, which began in early December 1877, was accompanied by intimidation, murder, looting, burning of houses, confiscation of property and mass deportation. What the Albanian and Turkish population had experienced from the Serbian army can be summarized in a Letter of Conveyance II No. 195, by the Ottoman representative Nikolaides, sent to the British representative Gould, written from Niš on November 23, 1879:

“… the Bulgarians and Serbs, who had even begun to wreak havoc and burn down the houses of the Albanians, in complete contradiction to the promises given to them by the Serbian commanders… They sent part of the looted goods to Belgrade, while another part to other cities in Serbia… As for the Albanians, who lived in the villages of Leskovci, Prokuplje and Kuršumlija… trusting the Serbian promises, almost all of them returned to their homes; after they returned to their properties, the Serbs invited them to a meeting, under the pretext of reviewing the measures that they should take for the development of the country; the most authoritarian and stubborn Albanians, who came to the meeting, were immediately shot. Unhappy with this inhuman act, the Serbs continued with the demolition and burning of Albanian homes, to rob and extort their property, to disarm all Albanians, and then to continue with murder in broad daylight, on the streets of villages, or wherever they encountered an Albanian”.

These brutal measures are also confirmed by Çubrillović, when in 1937, in the program “The Expulsion of Albanians”, he proposes the same measures that the Serbian state took against them in 1878: “There remains one more tool, which Serbia has used in practice after 1878, and this is the secret burning of Albanian villages and neighborhoods in cities”.

The number of those killed was never learned, while the extent of this tragedy and the number of displaced Albanians were described by the British officer, Aubrey Herbert: “After the Russian-Turkish war of 1877, when Niš and Vranje were ceded to Serbia, it was noticed that a large number of Albanians lived in these regions.

The Serbs expelled Albanians from their homes, took their property without any compensation and drove them into the mountains; 100,000 men, women and children were dispossessed. Many died of hunger or harsh weather on the way to the Albanian and Turkish provinces, where they were allowed to live in peace and security”628.

A description of the ethnic cleansing of this territory is given by Vasa Čubrillović:

He, due to the circumstances, when he makes this description (1983), initially tries to hide the order of Prince Obrenović, saying that: “The cleansing of the regions around Toplica and Kosanica from Albanians in 1877 and 1878, was probably not done by order and according to a plan from above…; This was done more instinctively, in the course of the war and during military operations…”

He then describes the course of the operations: “Starting after the penetration of the first Serbian lines in the direction of Kuršumlija, Prokuplje and Leskovci, they encountered dense settlements of Albanians, who did not want to surrender. The main war was waged by the Serbs with them. It was necessary to conquer the villages one by one. The Albanians mostly retreated south, retreated to the heights and continued the war.

When the Serbian army approached them in the heights, they retreated to the valleys of the South Morava, Veternica, Medvedja, Pusta Reka and Lebana, to continue further – to Kosovo. Thus, the Serbian chetas cleared Toplica of Albanians, acting step by step…”.

All this is explained more succinctly by Vladimir Dedijer: “After the decisions of the Berlin Congress… the government of the Principality of Serbia urgently ordered its army command to mobilize several divisions and place them on the front line, especially in the Toplica district, with the aim of expelling the Albanian population, giving them only fifteen minutes to take their livestock and the most necessary things. I heard this historical fact from Professor Vasa Čubrillović, whom I thank for his attention”.

Torture methods in 1912 among the Serbian soldiers

The entertainment of the Serbian komitas – Chetniks by killing Albanians, similar to Trotsky, is described by the newspaper “Radničke novine” dated December 18, 1912. In the article “For the Women to Read”, this newspaper, among other things, brings a method of entertainment, killing by torture, described by a Serbian soldier, who tells his wife in a letter:

“… Then they catch the komitas, who are like filthy savages and torture them terribly. One holds the rifle with a bayonet, the other sticks the Turk (meaning the Albanian, F. K.) in it and then takes him out, then the other catches him and sticks him again; and so on ten times they throw him on the bayonet, until he dies. It is terrible to watch… What kind of heart these people have – I do not know”.

Serbian soldiers raping Albanian women and forced conversions

The rape of women, as well as the forced conversion of Muslim and Catholic Albanians to Orthodoxy, was part of the program of this genocidal campaign, which also involved the Serbian and Montenegrin Orthodox Church:

“The heinous acts committed against women and girls, including children as young as twelve, are indescribable. To mark such horrors, the fathers and husbands of the victims, under threat of weapons, were forced to hold candles and witness the rape committed against their daughters and wives in their homes”.

Serbian soldiers betting on wether a pregnant woman had a boy or a girl, and killed the woman to see

“There were not a few cases when the Serbs seized pregnant women, placed bets on whether the child was a boy or a girl, and killed them to see”. The facts about the use of unbridled violence in order to convert Albanians are more than evident: “At the end of August, I went to the Shala highlands, where I saw the refugees from the province of Guci, who had been robbed by Montenegro, who were falling into a miserable state.”

These were those who remained from the massacres that were carried out in the name of Christianity. I asked real witnesses. Four Montenegrin battalions had spread terror in those parts. Muslims either had to be baptized or death awaited them… Many people were slaughtered, women whose faces had been uncovered had been baptized and in some cases even disgraced”.

That the Serbian and Montenegrin Orthodox Churches were involved in this genocidal enterprise is attested to by Mihailo Maletić, in “Kosovo”, published in Belgrade, 1973: “in Peja and Gjakova Metropolitan Dožić carried out forced baptisms of Albanians”. The forced conversion is also confirmed by Herbert, who in an article for “The Time”, dated September 22, 1913, writes, among other things:

“in various areas systematic conversion of religion, expulsion and extermination, dictated by politics, are continuing. These methods, as far as I can discover, were forgotten for a fairly long period, but have now begun again”.

Baptism, torture and murders among the Serbian soldiers in Peja

“In Peja, too, the same thing is attested: “baptisms were carried out with torture. People were thrown into the icy waters of the river and then made to bake near the embers of the fire, while they begged for mercy. And the price for all this was to convert to the Christian religion”.

An authentic testimony was left by the Catholic priest Zef Mark Harapi (1891-1946), who recounts the sadistic violence of Montenegrin soldiers against the Catholic inhabitants of the villages of Novoselle, Papić, Krushevs and Perlep in the Peja district. Under the pretext of searching for weapons, the Montenegrin army arrested the men of these villages and, “as night fell, they tied them by one hand to a fence, and with a stump they hit them on the face, chest and joints of their limbs.

Then, with a tin bucket (tin packaging, F.K) of kerosene, they poured water on their bodies. Imagine how much trouble those poor people must have endured in that frost when the water turned ice on their bodies. That winter, many Christians were tied with ropes by the throat and thrown into water canals, with all their clothes, then dragged to the bank of the canal, repeating this action several times. Many of them died in that cold water.

During these tortures, the villagers had two conditions; either to change their religion or to surrender their weapons. But the poor ones swore that they did not have weapons; and in order not to change their religion and the ancestors agreed to go through snow and ice, to cross mountains on foot for two days through the mountains of Gjakova to buy Mauzers up to 20 Napoleons and return to hand them over to the government…

Once they asked for weapons; we will bring you the weapons, then they said that you still have them and you have nowhere to go except to change your religion (In the original text in Gheg: “perpoosë qi m’u bâa shkjee”, F.K). About six people from our village (Novoselë) declared that they had handed over the weapons they had to the authorities in Peja and that they would not give them any more money or weapons, but we will not change our religion either.

Then they caught them, put them in ice water several times – then they crushed their hands with a large stone slab… There are two names that became famous among the people; one was Sava who lived in Gjakova and beat people to death, while those who escaped set off for Peja, and who were shot by the other Sava, who managed to kill up to 3,000 people inside the city…

The Peja prison, a tower located outside the city, known as the Jemin Pasha Tower, was filled with Muslims and Christians (Albanians, F.K)… Gospodin Sava, to show ‘honor’ to the prisoners, would go to the prison door himself and ask the prisoners; ‘whoever becomes a sheikh is saved, the others become patare’… It would have been heartbreaking to see them so helpless when they were sent to be shot in groups of seven or ten, with their hands tied behind their backs.

To see the pale faces of the shop owners, tearful and not daring to say a word, they were on the way to where their friends, the prisoners, were being sent. The place of the murder was outside the city. A large open pit, where the prisoners were lined up on its edge and turned their faces to the soldiers who were emptying twelve cartridges into each one, and the ones who were not able to do so fell and fell into their own graves…

The order of the Montenegrin government was clearly issued in the villages; either I was shot, or the death penalty… Those who dared to refuse to convert were beaten well and well, then they forcibly put their heads in a burning furnace and held them until their eyes burned; or they smeared their hands with kerosene and set them on fire; or with an iron device, they squeezed their heads until their eyes burst and their brains spilled out; or with a scream, men’s mustaches were pulled out thread by thread…

How many people disappeared without a trace! They were taken from house to house at night, taken to the vineyard hill, and there they were killed with bayonets and tortured… In just one week, the government executed 113 people because they did not listen to me, “Zef Harapi continues, describing how two units of the Serbian army, who had helped the Montenegrin army in pursuing the Kachaks in the Deçan region, had brought pigs with them and had put them in the Çarshia mosque and another in the Shuster neighborhood.

Then, the conversion of the inhabitants of Rugova by torture, in the presence of three Serbian priests, as well as the event of April 2, 1913, when the government and the Orthodox Church had forcibly brought to Peja the Albanians of the villages of Strellc, Grabanica, Isniq, Krushevc and Papiq, “big and small”, to convert them from Muslim to Orthodox, and how the ceremony was led by “Prota Pop Maksim”.

That conversion was one of the forms that Serbs and Montenegrins used in the function of ethnic cleansing is confirmed by a data from a scientific study by Mustafa Memiqi, born in Guci, “… In order to frighten the people, twelve personalities of Plav were previously executed. The people were ordered through a bullhorn to participate in the shooting and to cheer “Long live the King”… 8,500 were killed, and about 12,500 were converted…

The harsh military court did not condemn 800, but only 550, while 250 were executed without any trial, allegedly during the attempt to escape to Albania… They were killed on the doorsteps of houses, in front of the herd of cattle like shepherds, while they were officially treated as if they wanted to escape. In addition to the 800 killed, from February to May 1913, in the Plav and Gucia regions, 12,500 Bosniaks and Albanians were converted to Orthodoxy…

These data were made public by the Gucia priest Gjorgje Shekullarac in the newspaper. ‘Politika’, as well as Popivić, on March 2, 1941 in the ‘Ditarin croat’… Simultaneously with Plavë and Guci, conversion was also carried out in Dukagjin (Peć and Gjakova)… Luigj Palaj, the Catholic priest in the Gjakova district (village Gllogjan), on the occasion of conversion, had two fingers cut off on both hands, so that he could not make the cross according to the Catholic rule with five fingers, but, according to the manner required by the Orthodox canons, with three fingers… In February 1919, 450 citizens were killed… while the rest of the inhabitants temporarily emigrated”.

Burning Albanian homes as a practice among the Serbs

Likewise, setting fire to Albanian houses was part of the punitive actions: “The fires of the burnt villages were the only signal with which the various columns of the Serbian army informed each other of how far they had reached. Meanwhile, the Albanian population – if they had not been killed and those who had managed to escape – we pushed ahead of us and forced them, like the desperate, to watch as their houses burned down…”

“How can one forget the categorical order of the prefect of Kicevo, which he gave to the Serbian army, when returning from the Albanian border, to burn all the villages located between Kicevo and Ohrid”. Trotsky describes this phenomenon on December 23, 1912, in his authentic testimonies, after entering Kumanovo: “The darker the sky became, the brighter the terrifying illumination of the fires against it. (The burning overtook us too) the fire was all over us. Entire Albanian villages had turned into fire pits right up to the railway line.

This was the first authentic case I had seen in the theater of war, of the merciless mutual extermination of people… With all its fiery monotony, this scene was repeated all the way to Skopje” This practice continued even after the end of military operations. The newspaper “Radničke novine” of March 29, 1914, writes that:

“The rebel Albanians all fled across the Montenegrin border into Albania, while those who remained and were suspicious were summarily executed, and their houses were burned. 200 to 300 Albanians were executed. This happened in the area between Prizren and Suhareka and these were Albanians from these areas, who took up arms to protect themselves from the Serbian government”.

The effects of the Serbian atrocities

The effects of this ethnic cleansing of Kosovo are indicated by the following data: “The total number of those killed in the Vilayet of Kosovo is estimated at 25,000, a figure that is not exaggerated”. Meanwhile, the number of those expelled can be estimated from a 1913 report by the Carnegie Endowment. Some of the refugees from Kosovo and Macedonia, Albanians and Turks, found one of the escape routes by retreating to the port of Thessaloniki.

During the visit that the Commission made to the refugees in one of the camps in September 1913, “they found that about 135,000 immigrants had passed through Thessaloniki, starting from the beginning of the second war. Each steamer that left for Anatolia transported about 2,500”. This is the second wave of ethnic cleansing, while the data for the first is lacking.

It should be noted that this figure is not final, since the expulsion was still in process and this evidence does not include a part of the Albanians of Kosovo and Western Macedonia, who had fled to Albania, then groups that had retreated towards Bulgaria. These figures speak of a balance of over 160,000 people who suffered from the campaign of the Serbian state and from the total number of 639,000 inhabitants that Kosovo had at the beginning of the 20th century, it is estimated that around 479,000 remained in 1920, always including the Serbs.

Another piece of information, which is circulating on the internet and refers to a document of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, section of Historical Sciences (“Dokumenta o slonjoj politici kraljevine Srbije”, K.VII Sv.1 Belgrade 1980. p. 617-618), “says that from 1912 to 1914, 239,807 people were displaced from the Albanian areas of Serbia, Macedonia and Montenegro. It is emphasized that this figure does not include children who were under the age of 6″736, and then presents the dynamics of displacement over the months for three years:

Genocide

That the Serbian army’s undertaking against the Albanians in the Balkan wars, in terms of its purpose and scale, had a genocidal character, is proven by Tucoviq, when he describes its epilogue in “Radničke novine”, no. 223, October 22, 1913:

“Exactly these days it has been a year since the sorrowful Albanian tribes carried their cross to Golgotha. This is the year of the systematic extermination of the Albanian population in all the areas occupied by the Serbian army… These are not the streams of blood of armed people who went to war, no, but these are the streams of blood of the killed unarmed population, of innocent children, of women and peaceful people, of the working people of Old Serbia, of Albania, of Macedonia and Thrace, whose only fault is that they pray to God differently, that they speak a different language and that in their centuries-old homes they have naively welcomed four savage expeditions”.

After 57 years, in 1970, Yugoslav historiography confirms this invasion with extermination intentions and explains it thus: “In the First Balkan War in 1912, parts of the Serbian and Montenegrin army occupied Kosovo, Prizren and (Dukagjin) annexed the cities of Peja and Gjakova to Montenegro. At this time, the deterioration of interethnic relations in this province occurred. Terror against the Albanians of Kosovo occurred, which was inspired by the circles of power of the then Serbia and Montenegro. As a result, a part of the Albanian and Turkish population was forced to move to Albania and Turkey”.

Edith Durhams reports

An authentic description of the rebellion, which prevented the consolidation of Albanian statehood in its early days, was made by Edith Durham, reporting from the scene, who attributes the 1914 Haxhi Qamili Movement against Prince Vid to Serbian intervention, which Andriqi confirms 24 years later in the Elaboration on Albania of 1939. In this chronology of events Durham says:

“Esad, as we suspected, was a Serbian agent”. “News came that Osman Bali, one of the men who was said to have killed Hasan Riza in Shkodra, had been seen among the rebels, perhaps this time in the service of Esad”. “The Russians were as bad as the Italians. They too hoped for the fall of the city (Durrës).

The Russian secretary was a typical Slav, a nervous man. He was quite sad that the Albanian national party was showing itself strong and Albania had not yet been overthrown”. “The rebels now informed Durrës that they wanted to speak with an English representative. They trusted England. Then General Philips came from Shkodra to meet them. He reported that the leaders of the rebels were certainly not Albanians and refused to give their names.

One of them was a Greek priest. The Greeks this time wanted to encourage the Muslims to seek a Muslim king. With such cunning, they exposed Vid as ‘anti-Muslim’, hoping to divide Albania and destroy it more easily”. The chaos that was created by the rebellion forced Prince Vid to leave the capital of the principality, Durrës, on 3 September 1914.

Italy and Austria-Hungary, as two states that supported the independence of Albania, but that wanted to extend their influence in this part of the Balkans, had portrayed the key man of these events, Esat Pasha, as the instigator of this rebellion according to the antagonistic spirit that reigned between these states:

“In Vienna, Esat was considered little more than an Italian, Serbian, Turkish and perhaps even Greek agent; while in Rome he was considered the victim of a pseudo-nationalist conspiracy, inspired by Austria to destroy our position in Durrës”.

In fact, the events that followed proved that he had been sold out to the Serbs and organized the rebellion for their interests. During the time the rebellion lasted, Esat Pasha was under arrest by Albanian government forces. After his release from arrest, Yugoslav sources say that: “Esat Pasha is in Niš coordinating the assistance of the Serbian government to return and take power in Albania. At the end of September, he forms a government in Durrës”.

Serbian terrorism in 1914 in Sarajevo and the Serbian “retreat”

Terrorism, as an act through which political goals are achieved, has its origins in the Sarajevo assassination of June 28, 1914, when the Serbs, also provoked by the Russians, as part of their programs for a greater Serbia, killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife.

The goals of this assassination are best explained by the memoirs of J. Jovanović, left from a meeting he had with academician Lubomir Stojanović, a member of the Radical Party, MP, Prime Minister (1905-1906), Minister of Education, State Counselor during the First World War… As a strategy to create a Greater Serbia, at this time, the Serbs counted on the creation of a world chaos, from which Serbia would benefit. Stojanović explains this:

“We must fight Austria even if it occupies us for a while until Russia acts. Then it will be forced to withdraw from Serbia and hand over Herceg Bosnia, Vojvodina and everything to us”

This action was being prepared while the rebellion of Haxhi Qamili was in full swing in Albania: “On 27.05.1914, the final technical preparations for the Sarajevo assassination were being made in Belgrade. Milan Ciganović, Voja Tankosić’s confidant, handed over six bombs, four revolvers and a bottle of acid to Gavrilo Princip. Principi, Grabež and Čabrinović traveled by ship from Belgrade to Šabac”.

This was the terrorist group, which was formed by the head of the Serbian army intelligence service, Colonel Dragutin Dimitrijević – Apis, part of the terrorist organization “Unity is Death”, also known as the “Black Hand”, and which was also supported by the regent Aleksandar Karađorđević, who, according to the Serbian historian Boris Marković, “on one occasion he also helped financially with 26,000 dinars of the time. This happened just a few days before the assassination attempt in Sarajevo”.

This event became the initiator of the First World War. Under the accusation that the assassination was organized by Serbia, Austria-Hungary, on July 28, declared war on Serbia. After frontal fighting, which lasted until October 1915, the Serbian army was defeated and on October 29 decided to stop resistance and begin the escape.

The only path of salvation for the army, the king, the government and a large number of Serbian state and civil officials were the Albanian territories, in which this army, on the orders of the king and the government, had been causing massacres against the local population for three consecutive years.

On November 28, the government arrived in Shkodra, and on December 6, general command. In the history of Serbia, this retreat of the Serbian army through Albanian territories is known as the “Albanian Golgotha”, since “during the retreat through Albania, 77,455 soldiers were killed… Out of 200,000 civilians who passed through Albania with the army, 140,000 were killed or died”.

“The losses of the Serbs could have been even greater, if Esat Pasha had not remained loyal in those difficult moments”. The part of the soldiers and civilians who died during the passage through Albania died of hunger, cold, but also from the attacks of the Albanian highlanders. Now the Serbian army, which four years ago had left the scorched earth in the Albanian lands and had triumphantly entered the ports of Durrës and Shëngjin as conquerors, was standing there in a miserable state, waiting for the Allied ships to transport it to Crete, where it remained until 1917. This time allowed the Albanians of Kosovo, Montenegro, and Macedonia to breathe freely for three years and experience the liberation of the arrival of the Austro-Hungarian army”.

The body of Vehbi Kajtazi, massacred by Serbs, some time in the 20th century.

The Serbian Yugoslav invasion of Albania in 1919

The occupation of northern Albania – the “war” with civilians

The Paris Peace Conference of June 1919 confirmed Serbia’s access to the sea through Montenegro and Dalmatia. However, it did not give up the territories of Albania, undertaking military actions in Albanian territory, with the aim of putting the international factor before the accomplished act.

Thus, at the end of 1920, the Serbian army crossed the border of what was known as Albania by the London conference, with the idea of ethnic cleansing, so that, in the event of an eventual correction of the border, the ethnic factor would not be decisive. Since Albania did not yet have a consolidated army and forces of order, the Serbian army had no one to fight and, according to the Serbian press, it also waged this “war” against civilians – children, women and the like. How this enterprise unfolded, in summary, is explained by Vladimir Dedijer:

“…the troops that entered from Yugoslavia committed terrible crimes and during one action alone burned down 90 Albanian villages”. Another note says that in the attack of the Serbian army in the eastern part of Albania, “on the long front line from Luma to Martanesh.., 738 civilians were killed, and 6,603 houses were completely destroyed, and property was completely looted.

Because of an international order, which now began to be maintained by the League of Nations, the actions for the occupation of Northern Albania were camouflaged in two ways. First, through propaganda that the occupation was the will of the people. In order to “awaken aspirations for Albanian territory, in Peja, for example, the government organized in April 1920, a large gathering of all citizens of Peja ‘without distinction of religion and nationality’, in which a ‘voiced resolution’ was approved to beg the royal government to act through friendly powers ‘so that Shkodra passes to our kingdom”.

To show that all this was a farce, the authors, put in quotation marks the national affiliation of the participants and the demands in the resolution. Secondly, the actions of the Serbian army in the Albanian territory were camouflaged as being allegedly carried out in the name of clearing the terrain from the armed Albanian gangs, which came from Albania:

“The game of the Yugoslav government is reflected in the arming of the Albanian detachments – they were armed with Serbian weapons and ammunition, in uniforms sewn with money provided from the available fund of the Yugoslav government, these detachments ‘rushed’ into the Yugoslav territory, according to the order of the Yugoslav government itself.

Thus, the Yugoslav government was able to publish the telegrams about the ‘rushes of the Albanians’ and prepare the punitive expedition, the task of which would be to occupy northern Albania up to the Shkumbin River – so that, finally, the Albanian people would not live independently and peacefully”.

Serbian and Yugoslav atrocities in the 1920s

“Radničke novine” dated June 29, 1920, describes that these groups were organized by the chief of diplomacy Stojan Protić and the regional chief of the border with Albania Jovan Ćirković. They paid these groups with the aim of staging interventions against the army because “…since we reached the common border with the so-called independent Albania, these interventions became a real vital need of our Balkan policy”.

Further, on August 19, this newspaper continues: “… our government has decided to invade Albania… the government issues forged telegrams through newspapers about attacks by Albanians… our army will do everything to once again reach the Albanian coast through the territory and through the blood of Albanians… Pogradec on the southern shore of Lake Ohrid has been the first target of our occupation, both before and now, while the final goal is the occupation of Northern Albania up to Shkumbini.

The Yugoslav government’s staging of Albanian intervention in Yugoslav territory, with the aim of justifying military intervention in Albania, is also explained by Horvat, referring to two Serbian authors; Pavle Jovicević and Mita Milković, who “describe the games of the royal government; arming the Albanian troops, which then ‘enter’ the territory of Yugoslavia by order of the government itself. After this, a punitive expedition is sent against Albania, which turns into an occupation”.

Dedijer’s claim of “terrible crimes” by the Serbian army and gendarmerie during this intervention is also confirmed by the Serbian and international opposition press: thus the London newspaper “Spektator” dated September 4, 1920 publishes the article by Obrej Herbert:

“On August 14, the representative of the Albanian government in Paris, Mr. Konica (Mehmet, F.K) sent this telegram to Mr. Lloyd George: ‘… the Serbian army on August 14 suddenly intervened in Albanian territory in the direction of Shkodra and Dibra. The attacker is penetrating deep into the territory, bombing cities and villages, destroying everything in its path and terrorizing the people… it is obvious that this invasion is pre-planned and the aim is the destruction of the Albanian state and the extermination of our race…”

A complete picture of what happened during the Serbian army expeditions in Albania has been left by Dragisha Vasic, who was a participant in this campaign, mobilized with the rank of reserve captain. He, traveling from Prizren towards his command post, which was advanced deep into the territory of northern Albania, curses himself that once again, after the Balkan wars, he is in the territory that had been transformed into a “slaughterhouse of hell” and adds:

“The villages we passed through were empty, because a few days ago they were burned by our troops, after having been previously destroyed by artillery and only a few houses were emitting smoke from their chimneys, which shows that in them there are still people alive. These were spared, they are the houses of our trusted ones… In a very wide area across the Black Drin, enemy villages were burning for days… those that are burning, I think are Çezina, Grika, Araci, today they were set on fire.

That the expedition had the aim of exterminating the Albanian race, as Konica claims in his letter, is proven by “Radničk novine”, which publishes a letter from a soldier with communist convictions, who is part of these units, and who recounts the attack of the Serbian army in the Luma area, authorized under the pretext of pursuing the Kaçaks by the prefect (naçellnik) of the Dajić region, who writes:

“The victorious expedition after the seven-day action was carried out by demolishing houses, looting livestock and burning villages and was carried out at the head with Colonel Katanić and Prefect Dajić, returning with over 2,000 heads of sheep, goats, cows and oxen looted in poor Albanian villages, abandoned for fear of the Serbian army. Of the ‘kaçaks’, only one imam was captured in the mosque of the village of Kalis… for this (looting, F. K.) our units often attack Albanians.

Even the Albanians and the victims who become a result of this are a consequence of the plundering-imperialist policy that is being developed in Albania”… This same newspaper, on September 16, 1920, reports: ‘from the country, Peshkopi, September 1: …on August 27, 28 and 29, our people occupied the villages which, as soon as they were taken, were plundered and set on fire, leaving them to burn completely, while the people were left on the streets and in the ridges without shelter and without bread… a special company was combined to set fire to and destroy the villages.

When a general from the 3rd Army came these days and asked who was setting fire to the villages, Colonel Jasha Mihajlovic replied that the Albanians, before fleeing the village”…. September 17, 1920, “The Serbian army ‘liberated Peshkopi’. The villages are all burned on both sides of the Drin. The sight is terribly horrifying. The women and children are all taken out and then the house and everything around it is burned.

The looting is done to a large extent for the benefit of the officers… throughout the region the looting is done by the gendarmes and the communes, while for this the logistics of the army and the prefect are used, as well as many high officials, to whom the loot is handed over.

In addition to military intervention, “Belgrade attempted to interfere in the development of events in Albania, supporting the demands of its clients (Esad Pasha Toptan), or inspiring Catholic tribalism in the North (Marka Gjoni’s ‘Republic of Mirdita’).

This is also confirmed by Ivo Andriqi in his “Elaborate on Albania” of 1939, according to which, Yugoslavia at this time, through its agent Gjon Marka Gjoni, organized the proclamation of the “Republic of Mirdita”, which would join Yugoslavia, something that Vladimir Qorovic had also previously affirmed, when he said:

“Our government intervened in Albanian affairs and significantly influenced the development of events there. With its covert interventions in northern Albania, it helped create the Republic of Mirdita and, when it sent troops across the border, it provoked a protest in the autumn of 1921 from the British government and the League of Nations”.

Serb atrocities against civilians in 1924

A literary description of these circumstances is given by the Montenegrin writer Niko Joviqević (1908-1988), a general in the Yugoslav People’s Army, who himself was a settler and observer of this process: “In this situation, the Albanian side had all the moral legitimacy to protect its biological being and the basis of existence – the property, which the state forcibly alienated from them.

The Albanians killed, because they had had enough of the robberies; the Turks left, we came (the Montenegrins, FK); the Serbs left, the Germans came (the Austrians, F.K), the Germans left, the Serbs and Montenegrins came. And everyone snatched from the defeated what belonged to someone else, to them, to the Albanians. But no one for a long time: only the Albanians are eternal here and do not allow themselves to be touched.

They fled from home or left only for a while short in the mountains and killed from the well or by attacking in an organized or open manner”793. This resulted in the organization of groups of Kaçaks, which were associated with the name of Azem Bejta (1889-1924), and which began the resistance against Serbian rule.

This resistance, which continued until 1924, does not appear in any official Serbian report or in the press of the time to have taken action against the local Serbian civilian population, while, on the other hand, the army, gendarmerie and engaged Serbian civilians used the expeditions against the Kaçaks to vent their chauvinistic anger against civilians, massacring entire Albanian villages:

“The Kaçaks attacked state bodies, but also some settlers, who came to the Kaçaks’ lands, because they were clear that they came to serve the establishment and strengthening of the new government”… “According to the data and statements of the first settlers, in most cases the Kaçaks did not attack those settlers who settled on uncultivated lands and forest lands.

The settlers’ villages were attacked at night by people from (the settlers, F. K.) the neighboring village, with the aim of expelling the families from there and those attacks attributed to the Kachaks”…“The state bodies, the gendarmerie and the army, since they could not destroy the Kachaks, punished their families, sending them to camps…

The Kachak families had all their property confiscated, there were cases when their houses were also burned… During the occupation of individual Albanian villages, by burning houses and destroying property, the army and the gendarmerie committed atrocities against the innocent population, killed women, children and displaced entire villages…

Burning of houses and expulsion of Albanians from their homes, who were replaced by settlers, also occurred in other villages of Kosovo – Kërnina, Kabashi Jabllanica, Harilaçi… The total confiscated property of the Kachak families in the districts of Kosovo covers an area of 3,759.51 hectares.

A profile of the Kachaks – the freedom fighter, can also be found in the novel by N. Jovicević: “The Kaçaks are something special both in the fantasy of children and in the fear of adults. According to the worldviews of Albanians and Montenegrins, they are not Cubans, but fugitive warriors due to injustice, who cause admiration, envy due to their bravery and fear.”

That brutal measures were taken on the ground, Bogdanović confirms in a few words: “There have been many uprisings, for example the Llap uprising of 1920, which was brutally defeated (Prapashtica, Knina, Kabashi, Jabllanica, Arilaqi (Harilaçi, F. K.)796. We understand the extent of Bogdanović’s “brutality” from a report dated June 21, 1921, of the prefect of the Kosovo district, with whose authorizations the punitive expedition of January 1921 was undertaken:

“in the village of Prapashtica, for example, after the suppression of the Llap uprising, where cannons were also used and where not a single house remained undamaged”797. In a published monograph on this massacre, it is stated that in Prapaštica alone, “during this expedition, 80 houses were burned and 1,020 people were liquidated, while in Keqekolë 574 people”.

The Serbian newspapers “Vreme” and “Pravda” provide cursory information about these expeditions, as information from the field was reserved. The newspaper articles covering these events are mainly taken from government communiqués and from secondary sources. In relation to the largest expedition undertaken, in mid-June 1924, these newspapers report on the killing of 200 to 300 Kaçaks and mention the participation of Montenegrin settlers in this expedition, as well as the use of artillery against four villages where the expedition was undertaken:

Galica, Zubovci, Mekušica and Lubovec. In none of the articles of these newspapers covering this event from 14, 15 and 16 June, nor The Ministry of Internal Affairs’ communiqué of 16 June does not mention the number of civilians killed. The extent of the suffering of the civilian population can be understood from the descriptions that the newspapers give of the end of the expedition:

“The villages where the fighting took place were turned into piles of collapsed stones, with a bloody corpse hanging in the middle of them on broken beams”.

Serbian massacres against Albanians of Dumnica of Vushtrri in 1924

A chilling testimony of the massacre of civilians, in the name of the war against the Kachaks, which was not published by the Serbian press, but which can be taken as a sample of what happened in those areas where the Serbian army and gendarmerie passed, is described by the three Albanian priests; Don Gjon Bisaku, Don Shtjefën Kurti, Don Luigj Gashi, in the Memorandum which they sent to the League of Nations in Geneva on May 5, 1930, where, in the section “Mass violence”, they present data on the massacre in the village of Dumnica:

“In Dumnica, Vushtrri district, on February 10, 1924, by order of the prefect Lukić and major Petrović, the village was surrounded and burned with the intention of burning all the inhabitants alive. Their fault was this: the gendarmes wanted to capture the kaçak Mehmet Konji, but without success. After the kaçak escaped, the authorities blamed not only Mehmet Konji’s relatives, who were all massacred, but also the entire village. 25 members died in this fire, among them 10 women, 8 children aged 8 and 6 people over 50. No one has been punished for this horror.”

Serb vojvoda Milic Krstic and his atrocities

This was the picture of the development of events that permeated the process of “pacification” of Kosovo by the insurgents!

In addition, this Memorandum provides information about the massacres committed in the name of the war against the Kachaks in other parts of Kosovo and Macedonia, confirmed by the names and dates of those who suffered and those who caused this terror.

One of them is that of “a Serb named Milić Krstić from the Istog district, (who) formed a group for the war against the Kachaks of more than 80 people, with whom he circulates throughout Metohija, raids, loots, burns houses and mainly kills innocent people, while he turns a blind eye to the fighting with the Kachaks”.

Krstić, “within one day, with his supporters, killed 60 Muslim Albanians in Jabllanicë (on July 9, 1921), among whom was also the influential personality, Osman Aga Rashkovci, the family sued Krstic in court. Since the guilt was very clear, the authorities declared Krstic dead, in order to save him, even though he still lives well in Istog, Peja district”801.

Perhaps these data would not have had their full relevance if they had not been a supplement to the report of the Minister of the Army and Navy of October 28, 1940.

Denunciation of the genocide in the League of Nations

Unable to denounce these acts, which also contradicted the constitution and laws, in 1924, the Albanians addressed a petition to the League of Nations, in which they emphasized that “Yugoslavia has organized armed gangs, which are terrorizing the Albanian regions and destroying numerous villages. After each destruction, colonization with Russian, Montenegrin and Serbian settlers follows.

On the other hand, farmers and citizens of Albanian nationality are having their fields taken away with the justification of the application of the agrarian law”. Of course, Serbian diplomacy had justified these as untrue, relying on their constitution, which guaranteed equal freedoms for all citizens.

We learn about the rampant violence against Albanians in the Yugoslav state from a document called “Order of the Chief of the Information Department of the General Staff – Belgrade, addressed to the Yugoslav military delegate in Tirana, Pov. Br. 11013, Belgrade, August 23, 1930, which requests “that the Memorandum of the Albanian priests be submitted to this body”.

With the act Pov. Br. 702, dated September 5, 1930, the military delegate in Tirana returns a copy of the Memorandum, which reflects concrete and detailed data on the rampant sadistic violence of the Serbian state authorities against the Albanian civilian population.

The Memorandum was drafted by Albanian Catholic priests: Don Gjon Bisaku, Don Shtjefën Kurti, Don Luigj Gashi and on May 5, 1930 it was submitted to Erik Drummond, Secretary General of the League of Nations in Geneva.

In this memorandum, the clerics first state the goals of the Serbian state policy for the institutionalization of the extermination of the Albanian people in the areas of Kosovo, Montenegro and Macedonia.

According to them, “this policy, already very rich in disasters and flare-ups, consists of this sentence: to change at any cost the ethnic character in the regions where Albanians live”. They then continue by describing the methods that the Serbian state structures apply on the ground with the aim of exterminating the Albanian population. According to them, the methods are as follows:

a. “Persecution of any kind, with the aim of forcing us to migrate;

b. The use of violence for the forced assimilation of the population, which is

not able to defend itself;

c. The persecution and disappearance of elements who do not want to leave the country or who do not accept Serbization”.

According to the evidence presented in this memorandum, it results that from this extermination methodology of the Serbian state structures have suffered:

“140,000 and more Albanians, who have been forced to leave their homes and property and move to Turkey, Albania and other neighboring countries, wherever they hoped to find shelter, a share of bread, especially a larger humanity”.

The second category, which has been subjected to violence for the purpose of assimilation, according to this evidence, includes the population of “800,000 to 1,000,000818 Albanians, the majority of whom are of Islamic faith, which lives compactly in the provinces near the border of Royal Albania, to the east, which in the north goes as far as Podgorica, Berane, Pazar i Ri, touching in the north and west the Morava valley and continuing west to the Vardar valley”.

And “The last category includes Albanian personalities in Yugoslavia who are increasingly persecuted because of their national feelings, as well as those who try to stop the denationalization, of whom the last victim is our brother in Christ, the venerable Franciscan Father Stefan Gjeçovi, who was ambushed by the gendarmes and killed on October 14 last year”

In the summary section regarding Serbian actions in Kosovo, the three priests provide data that prove the genocidal character of Serbian policy, through which it was installed in Albanian territories after 1918. These data include: “12,371 killed, 22,110 imprisoned, 6,050 houses destroyed, 10,525 families robbed”.

This memorandum provides information about methods of terror undertaken by the Serbian state, among the most absurd; one of them is the imprisonment of Shtjefën Gjeçov six months before he was killed, because he “had been involved in the reconciliation affair of two feuding Albanian families”821! Or the order of sub-prefect Sokolović for the Albanians of Reka (Bad Reka in Gjakova, F. K.) “to wear Serbian hats”.

Part of the memorandum is also information about the care that the Serbian state had shown in its relations with Albanians to hinder their political activity within the framework of the only legal organization “Xhemijeti” (Union), which represented the Muslims of Yugoslavia, and which it had eliminated in various ways: “The chairman Ferat Bey Draga received 4 years of imprisonment, Nazim Gafurri was wounded (March 11, 1927), then killed (May 7, 1928) in front of the gendarmerie station in Prishtina, Ramadan Fejzullahu was sentenced…”.

Of course, while collecting this voluminous information in illegal conditions, the three priests encountered difficulties, from which, during the collection of information, even minor errors were made. The Yugoslav state used these and the fragility of the League of Nations to minimize the effects of the “Memorandum”:

“The Yugoslav representative in the League of Nations, Šumenković and others, have defended Yugoslav policy in Kosovo and Metohija in two ways: they have used the erroneous names of various localities in the Memorandum of the Catholic clergy to invalidate the essence of their statements and then, they say that the Albanians in the southern regions, due to backwardness and lack of education, still do not feel the need for schools, for the press and for cultural-educational institutions and therefore this is the only reason that there are no such schools and institutions in these regions”.

Serbian atrocities in 1943 and Slavic colonisation

Due to the circumstances in which Serbia found itself during World War II, its quisling government did not have the space and opportunity to act towards Albanians, Germans and Hungarians. During this time, it was oriented and contributed to the anti-Jewish campaign and provided its assistance in their imprisonment and liquidation, as well as the Roma, in the concentration camps that had been set up in Serbia.

As for ethnic cleansing, on the ground were the Chetnik operational units of Draža Mihajlović, who operated in western Serbia, Bosnia and Montenegro, and who were involved in horrific massacres against the civilian Muslim-Bosnian and Albanian population in the Sandžak of Novi Pazar and in the northeastern part of Montenegro, where there was a Muslim and Albanian population.

The goals of Draža Mihajlović’s Chetnik movement against non-Serb ethnic groups are described in a report signed by Major Pavle Đurišić, commander of the Lim-Sandžak Chetnik headquarters, dated 13 February 1943, in which he informed Draža Mihajlović, as Chief of the Central Command, about the outcome against Muslims in the districts of Plevla, Čajnica and Foča.

According to this report, during this action “1200 Muslim fighters and 8,000 other victims: women, elderly people and children” were killed. The Chetnik movement of Draža Mihajlović had within itself the National Central Committee of the Ravnagora Movement, as a consultative body on political issues. This committee consisted of eight Serbian intellectuals, among whom Dr. Stevan Molević stands out as a prominent lawyer and member of the Serbian Cultural Club.

After the capitulation of Yugoslavia, he joined Mihajlovic’s Chetnik units and was the initiator of the drafting of the study “Thoughts on its borders, legal order and relations with other Balkan countries”, drafted in the spring of 1941 and presented in Nikšić, in June of the same year. This program-elaborate, Molević drafted in consultation with Dragiša Vasić, who was part of the Chetnik central headquarters and a member of the committee, as well as with Zarije Ostojić, chief of military intelligence in Mihajlović’s headquarters.

The main point of importance of this program is mainly related to the position of Serbia in the future Yugoslav state, where special emphasis was placed on the definition of the border with the Croats and the issue of national minorities. The program was drafted in the spirit that: “Serbs should have hegemony over the Balkans, but, in order to have hegemony over the Balkans, they must first have hegemony over Yugoslavia”.

The solution was envisaged by first creating a “homogeneous state of Serbia”, which would have defined borders, as the author of this program states that “the fundamental error of our state regulation was that in 1918 the Serbian state borders were not regulated. These borders should be regulated and should include the ethnic space in which the Serbs live, with free access to the sea for all Serbian regions, which are located near the sea”

The territory that would include Greater Homogeneous Serbia, according to this program, was: “… in the east and southeast it would include Serbia and South Serbia – Macedonia and Kosovo, to which the Bulgarian cities of Vidin and Kyustendil would be attached; in the south – Montenegro, Herzegovina and Northern Albania; in the west – Bosnia, Northern Dalmatia, the Serbian parts of Lika, Kordun, Baranja and parts of Slavonia.

The Dalmatian coast, from Šibenik to Montenegro, would belong to Serbia… point b. The northern part of Albania, in case it does not gain autonomy”. Meanwhile, Yugoslavia, with Homogeneous Serbia inside, according to this program, would consist of three peoples; “Serbs, Croats and Slovenes”, with well-defined ethnic territories, where, according to Molevic, “the war situation should be exploited and at favorable moments the territories marked on the map should be occupied and cleared before someone takes over the key places with strong forces: Osijek, Vinkovci, Slavonski Brod, Knin, Šibenik, Mostar, Metković and the territory with the mentioned cities should be freed from the non-Serb element: the guilty should be immediately punished, while the others should be expelled, Croats in Croatia, Muslims in Turkey, eventually in Albania, and the vacated territories to be colonized with Serbian refugees who are in Serbia”

The issue of non-Slavic ethnicities in this program would be resolved according to the projection for Croats and Bosniaks remaining within the territories of “homogeneous Serbia”, while on the basis of Chetnik actions in the field, the approach based on Nazi ideology, which this organization has towards minorities, is implied. The method of ethnic cleansing from non-Serb elements is regulated by Chapter II of the “Program of the Chetnik Movement, September 1941: worked on the Moleviqi Program:

“Preparations so that in the days of the break (the fall of Nazism, F. K.) the following actions can be undertaken:

a. To punish all those who criminally served the occupier and who consciously worked for the extermination of the Serbian people;

b. The de facto limitation of Serbian lands and arrange for them to be inhabited only by Serbians;

c. Special attention should be paid to the radical cleansing of the cities and their filling with fresh Serbian population;

d. Drafting a plan for the cleansing or relocation of the rural population with the aim of homogenizing the Serbian state community;

e. In the Serbian part, the Muslim question should be taken as a difficult problem and, if possible, resolved at this stage”.

Serbian Yugoslav Secret Police atrocities in the 1950s – 1960s

The events that followed confirm the murder organized by the UDB, because they accused our family and relatives of having committed the murder, through blackmail and violence they tried to create discord and suspicion between our families. Therefore, the entire neighborhood, men and women over the age of 16, were interrogated by the UDB and tortured on the pretext of having killed their son.

The UDB went to raid the deceased’s family, supposedly to find material evidence of the murder. In the cold of that February, as the grandfather said, they took out the deceased’s sister-in-law, who was in labor, as she had given birth to a son that night. Under the pretext that the knife with which the execution was carried out was under her bed, they took her out, keeping her in the cold until the raid was carried out. As a result, two days later the baby also died.

The next event that had shaken our small neighborhood of Muhaxhirëve was the murder of Sabit Ramadani, from the family of my great-grandfather’s uncles, who, together with our family, had been expelled from the village of Pllanë e Vogël in Toplica in 1878. Sabiti had been working as a policeman in Viti since 1948, and on the night of February 26, 1951, he was allegedly “accidentally” killed by a Serbian policeman during patrol.

In fact, the murder had been organized by the UDB, in order to intimidate and expel him to Turkey. These two stories, and one that occurred at the end of World War II, when the partisans had wanted to shoot all the men in the neighborhood and when a Serb from Shilovo named Živko had saved them, filled the background of daily events; Those from newcomers to the family, at regular evening meetings, were recounted in full or in parts, or in context, and were usually commented on in combination with 100-year history and with what daily politics produced after the events of 1981.

Serbian war crimes in 1998-1999

- The body of Ali Bejtullah Selim, born on 15.04.1937, executed by beheading;

2. The body of Nezir Hasan Ramushi, born on 16.02.1929, crucified on oak branches and executed by beheading. Both were executed on 13.04.1999, by the police, army and Serbian civilians, and the bodies were found decomposed on 17.06.1999 (after 65 days), on the outskirts of the village of Llashticë, Gjilan municipality. On April 13, 16, 20, and 30, 1999, the Serbian army and police, in cooperation with Serbian civilians from Pisjan and Zhegra, looted and burned Llashtica, and massacred 24 civilians, the youngest of whom was a one-month-old baby and the oldest 81 years old. The photos are from a recording made by Fatmir Bllaca, published by Sylë Murseli at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T-JKT2YQrbA , updated on 24.01.2024

Serbian war crimes in Llovcë of Gjilan.

On 04.04.1999, the Serbian police and army launched a campaign to clear civilians in the village of Llovce, Municipality of Gjilan. During the campaign, seven people were killed and a one-year-old girl (Marigona Azemi) was injured. The influence of the ideology of genocide on the Serbian troops is evident from the passion with which the victims were executed, who were then burned.

Photo: The burned bodies of teachers Rrahim Ymerit (1954) and Xhevrije Zeqiri (1944), from the village of Llovce.

Source: Archive of the Council for the Protection of Human Rights and Freedoms – Gjilan.

More than 20 bodies burned by the Serbian army were found by NATO soldiers in a barn in Kruše e Madhe. Source: Ed Oudenaarden /ANP/AFP

The same Serbian war crimes committed in 1912 were committed in 1998-1999

In 1989, I read Dimitrije Tucoviq’s collections and, among the chilling stories, I was impressed by a description of the Serbian army’s behavior towards Albanians and Turks in the Balkan Wars (1912-1913), where he describes the killings of the civilian population, rapes, the burning of villages, looting and expulsion. It was hard to imagine that after eighty-six years of this event we would witness such scenes:

We experienced the looting and expulsion beyond the Bjeshkët e Nemuna, when, at the beginning of the march on April 16, 1999, we witnessed the entertaining scenes of the Serbian army:

“first, the looting under the threat of weapons that whoever did not hand over all the money and jewelry would have their family executed, and then the forcing of the elders and the young to sing in Serbian the Serbian nationalist song “Who says, who lies that Serbia is small”, and the death run – the killing of young boys from the village of Malishevë, who were taken from the column, ordered to run and told that whoever would be the last to remain would be executed. Over 1,000 people of all ages witnessed these young men, running for their lives, being shot and both of them falling to the ground. Then they forced their neighbors to dig the holes to bury them, but not letting them use shovels, except with their hands”.

Before they even reached the outskirts of the village, our houses began to be looted and set on fire. The column of deportees, led by the Serbian police, moved along the city center of Gjilan, in the direction of Ferizaj, while both sides of the road were filled with Serbian citizens, who, with cheers and whistles, applause and shouts of “do you love NATO”, “Go to Albania, here is Serbia”… accompanied the column to the outskirts of the city.

At the entrance to Kllokot, a Serbian civilian, who was plowing his field, as soon as he saw the column of deportees, put down his hoe and took his rifle, went out into the street and, under threat of killing us all, began to rob women, the elderly, and children, taking what the previous looters had left behind. We witnessed and experienced the Serbian state’s genocide of Albanians during 1998-1999 and the implication of Serbian civilians in the crimes.

And now, after two decades, we are seeing that the mentality of hatred towards Albanians is still present among the Serbian political, church and intellectual elites, which is manifesting itself in various forms, while the most pronounced is that of the rehabilitation of the criminals who ordered and committed genocide in Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina, to whom the government is glorifying, erecting monuments and naming streets and squares in Serbian cities after them.

This and the creation of the argument for Kosovo as Serbian land, by fabricating additional arguments that once again dispute Albanian autochthonism in these areas, is a strong signal that after all that has happened in these 100 years, the Serbian political, academic and church elites have not given up on their goal, which is expulsion, to ethnically cleanse Kosovo.

The exposing of Serbian propaganda

If Albanians had cultivated hatred for their Serbian neighbors for centuries, the least they could have done during the Ottoman rule and Nazi-fascism was to raze medieval churches and monasteries to the ground, which at the very least have been and are in the service of religion, which have been and continue to be the place where hatred and xenophobia are produced, from where extermination projects against Albanians are designed and blessed.

Albanians proteced the Decani monastery

“Regarding this issue, Milan Kovačević, a member of the Serbian Philosophers’ Association, linking the survival of Serbian churches and monasteries to Abu Simbel, Egypt, says: “They came to our days preserved, they survived the Turks, who did not destroy them – they had 500 years to do so, they did not destroy the Albanians of Kosovo, even during the years 1915-1918, or even 1941-1944, when there was no Serbian power. We are mentioning an Albanian family, who for centuries preserved the Dečani monastery at the cost of their lives”.

Serbian authorities organize riots among Albanians to damage Orthodox monuments and the Serbian destruction of Albanian monuments

One such case occurred in 2004, when the riots of March of that year: “left nineteen dead (nine of these Albanians), 954 injured and 4,100 displaced. At least 730 houses owned by minority communities, twenty-seven Orthodox churches and monasteries and ten public buildings, providing services to minorities, some of the Serbian churches and monasteries were damaged by Albanian protesting crowds”.

But this did not happen by a prior plan of any Albanian political organization, it was a storm, which was organized by the Serbian intelligence services, which aimed to antagonize the Albanians with the international community and balance the barbaric behavior of their army towards cultural heritage, when in 1991 they bombed the center of Dubrovnik, as part of the world cultural heritage, protected by UNESCO, when they “destroyed 534 mosques in Bosnia and Herzegovina and in Kosovo, 218 Islamic religious objects.

They, taking advantage of the emotional state of the Albanian population for the 10,500 killed by the Serbian state during the period 1998-1999, touched the wound that was still oozing, manipulated the crowds for political purposes.

Testimony from a Serbian Colonel

In the interview with Colonel Momir Stojanović, Chief of the Serbian Army Intelligence Service (VBA), conducted by the journalist of the NIN Magazine, Miloš Antic, he proves the implication of these services in the events of March 17, 2004. To Antic’s question about the situation in Kosovo, Stojanović’s answer gives a clear message:

“In the last year, we have managed to renew it, that is, to ensure operational presence right at the head of the separatist movement, at the head of the terrorist organizations (“terrorists”, a pejorative for the Kosovo state structures. F.K), which operate there and which have branches in southern Serbia. Now we have an increased number of operatives there, even in the right positions, from which we can follow everything”. “NIN” Magazine, Belgrade, 01.10. 2004. Stojanović, is the organizer of the Meja massacre of 27 and 28 April 1999, “where at least 350 civilians were killed in this area, thousands of villagers were expelled and their property was looted or destroyed. Among the killed civilians, 36 were minors and 13 are still missing”. Source: Fond za humanitarno pravo, “Dosije: Operacija Reka” 2015, Belgrade, p. 13.

Sources and references.

Fadil Kajtazi. IDEOLOGJIA SERBE E GJENOCIDIT ( Analizë nga burimet serbe dhe ndërkombëtare ) BOTIMI I NË GJUHËN ANGLEZE. 2025.

ISBN 978-9951-980-02-9. Katalogimi në botim – (CIP)

Biblioteka Kombëtare e Kosovës “Pjetër Bogdani”.

End of Part One.