Abstract

This article examines the marginalization and suppression of Arvanite (Albanian-speaking Orthodox Christian) populations during the formation of the modern Greek state in the nineteenth century. Drawing on contemporary British and Venetian sources, particularly early Greek Gazette reports, it highlights the widespread use of Arvanitika across southern Greece and the deliberate policies that excluded it from education and public life. The study argues that linguistic repression was a central instrument of nation-building, aimed at enforcing cultural homogeneity rather than accommodating historical multilingualism. While Arvanites actively participated in civic, educational, and revolutionary life, their language was stigmatized as inferior and gradually erased from official recognition. The article situates this process within broader debates on nationalism, assimilation, and minority exclusion in modern Greece.

The creation of Greece

The formation of the modern Greek state in the nineteenth century was accompanied by intense efforts to construct a unified national identity centered on the Greek language, Orthodox Christianity, and an idealized continuity with ancient Hellenism.

Within this framework, populations that did not conform linguistically or culturally to the emerging national narrative—despite their participation in the Greek War of Independence and their Orthodox faith—were increasingly marginalized. Among these groups were the Arvanites, Albanian-speaking Orthodox Christians who had been established in southern Greece for centuries.

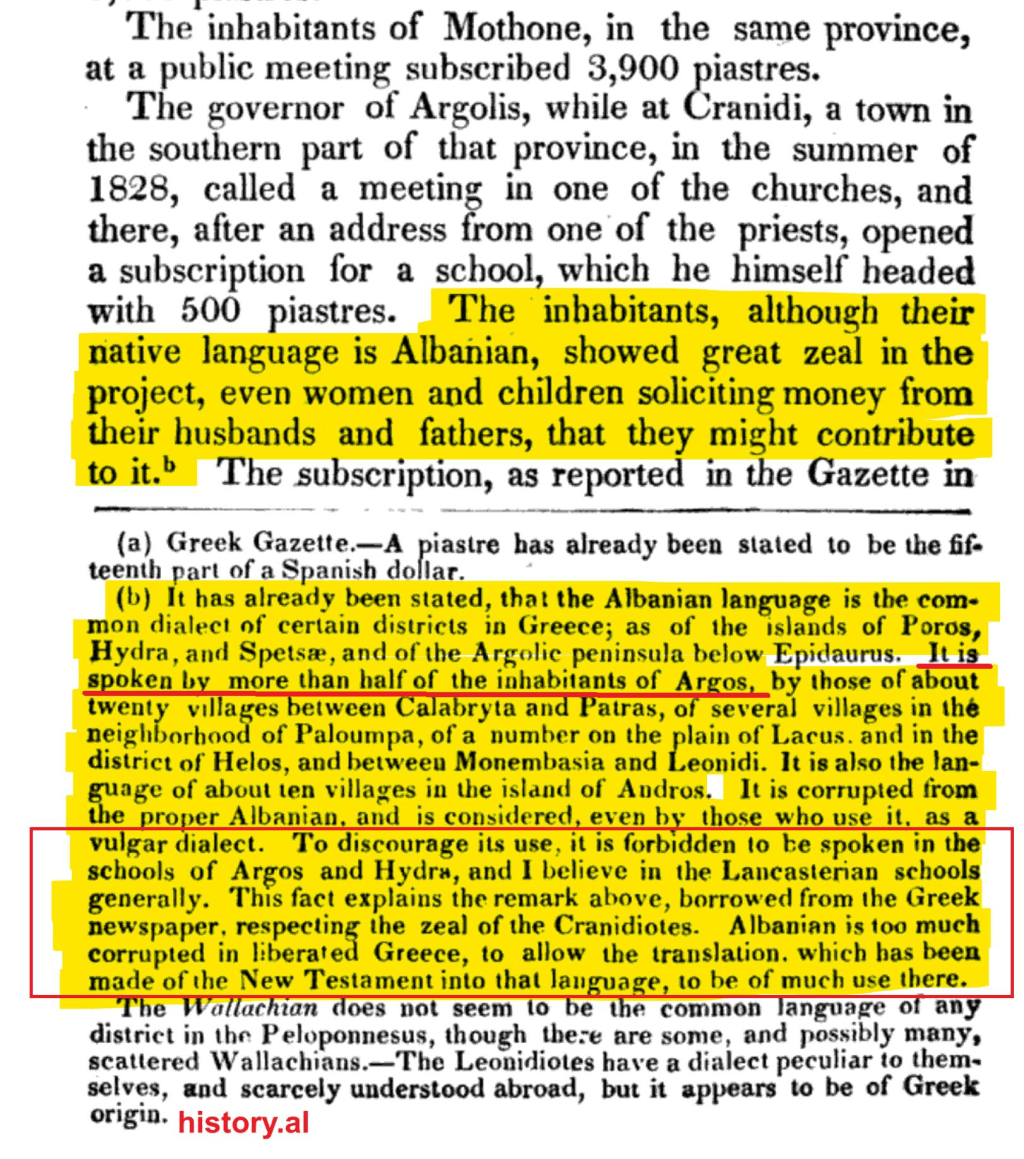

A revealing contemporary source highlights both the presence of Arvanites and the mechanisms of their marginalization. Writing in the late 1820s, an English-language account reports that the inhabitants of Crannidi (modern Kranidi) enthusiastically supported the establishment of a school, despite the fact that “their native language is Albanian.”

The passage emphasizes their civic engagement and commitment to education, directly contradicting later nationalist portrayals of Arvanites as culturally backward or politically suspect. Women and children are described as actively contributing to the fundraising effort, underscoring the depth of local participation in public life.

However, the accompanying footnote exposes the coercive linguistic policies of the nascent Greek state. It explicitly states that Albanian (Arvanitika) was widely spoken across large areas of Greece, including Argos, parts of the Peloponnese, Attica, Euboea, Hydra, Spetses, Poros, and Andros. In some regions, such as Argos, it was reportedly spoken by more than half the population. Despite this demographic reality, the language was characterized as “corrupted,” “vulgar,” and inferior—even by its own speakers.

Crucially, the text notes that Arvanitika was forbidden in schools, specifically in Argos and Hydra, and likely in Lancasterian schools more broadly. This prohibition constitutes a clear example of institutional linguistic repression. Education, rather than serving as a space for multilingual inclusion, became a tool for forced linguistic assimilation. The ban on Arvanitika aimed not merely at encouraging Greek literacy, but at actively erasing a living language from public and intergenerational transmission.

The consequences of these policies were profound. By stigmatizing Arvanitika and excluding it from formal education, the Greek state accelerated language shift and cultural silencing. Over time, Arvanite identity was redefined: Arvanites were expected to identify exclusively as Hellenes, while their language and distinct historical experience were rendered incompatible with the national narrative. This asymmetry is striking—Arvanites were required to become Greeks, yet Greekness was defined in a way that excluded Arvanite linguistic heritage.

The source further observes that the Albanian translation of the New Testament was deemed unusable in “liberated Greece” due to the perceived corruption of the language. This assessment reflects not a neutral linguistic judgment, but an ideological one: Arvanitika was denied legitimacy as a language of education, religion, or culture. Such exclusion reinforces the broader pattern of cultural suppression rather than mere administrative standardization.

In sum, the evidence illustrates that the integration of Arvanites into the Greek nation-state was not a neutral or voluntary process, but one shaped by systematic linguistic repression and cultural devaluation. While Arvanites were celebrated as patriotic Greeks when politically convenient, their language was banned, stigmatized, and ultimately pushed toward extinction. The nineteenth-century Greek state thus presents a case in which national consolidation was achieved not only through liberation from Ottoman rule, but also through the internal suppression of minority identities.

Sources

Finlay, George. History of the Greek Revolution. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons, 1861.

Finlay, George. The Hellenic Kingdom and the Greek Nation. London: John Murray, 1857.

Herzfeld, Michael. Ours Once More: Folklore, Ideology, and the Making of Modern Greece. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1982.

Herzfeld, Michael. Cultural Intimacy: Social Poetics in the Nation-State. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Kitromilides, Paschalis M. Enlightenment and Revolution: The Making of Modern Greece. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013.

Skendi, Stavro. “Crypto-Christianity in the Balkans under the Ottomans.” Slavic Review 26, no. 2 (1967): 227–246.

Trudgill, Peter. “Language and Identity in Southeastern Europe.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 21, no. 4 (2000): 237–248.

Tsitselikis, Konstantinos. Old and New Islam in Greece: From Historical Minorities to Immigrant Newcomers. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

(Includes discussion of minority policies and linguistic suppression.)

Wilkinson, Stephen. Xenophobia and Nationalism in Modern Greece. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Wace, Alan J. B., and Maurice S. Thompson. The Nomads of the Balkans. London: Methuen, 1914.

(Early ethnographic observations on Albanian- and Vlach-speaking populations.)

The Greek Gazette (1820s issues), cited in British travel and diplomatic accounts of early independent Greece.

Magno, Stefano. Annali Veneti (English excerpts and discussions in secondary literature on Venetian Greece).