by Fahri Xharra. Translation Petrit Latifi

Medieval funerary monuments of the Illyrian-Catharo-Thracian tradition in Bosnia, Montenegro and Serbia. The funerary monuments of this tradition were not simply grave markers, but Illyrian-Catharo-Thracian identity and spiritual statements.

The medieval funerary monuments known today under the Slavic term stećak represent one of the most significant phenomena of funerary culture in the Western Balkans during the 12th–15th centuries. However, despite later ideological appropriations, these monuments are not a Slavic creation, nor a direct product of the Orthodox or Catholic churches. They are an expression of an autochthonous Balkan tradition, with deep pre-Slavic roots, closely linked to heterodox Cathar-Bogomil Christianity.

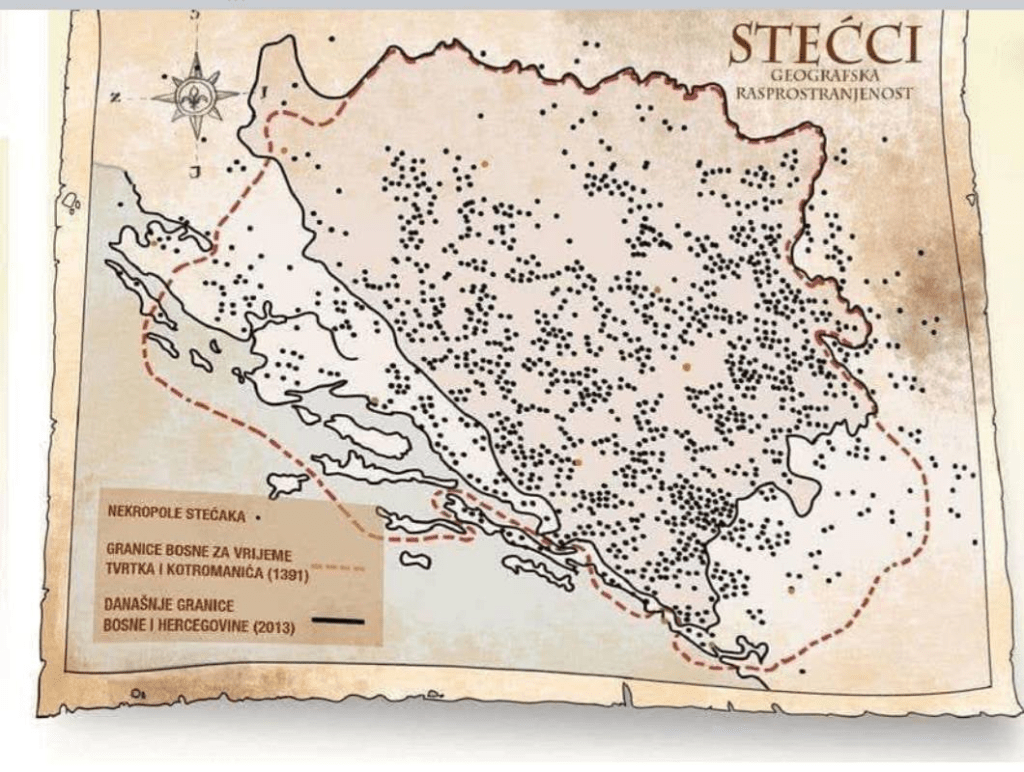

The geographical spread of these monuments – mainly in Bosnia and Herzegovina, but also in Montenegro, Serbia and inland Dalmatia – coincides with areas where the strong presence of non-canonical communities and of the local population that preserved elements of the Thracian-Illyrian heritage is documented.

Here the word “Thracian” is not used as a pure medieval ethnicity, but as a cultural and symbolic substrate, inherited from antiquity and transformed in the Middle Ages.

The iconography of these monuments is essential for their meaning. The solar, lunar symbols, spirals, rosettes, knights, hunting, ritual dancing and the frequent absence of the canonical cross indicate a worldview that does not correspond to Orthodox or Catholic doctrine. This symbolism clearly coincides with the religious dualism of the Cathars and Bogomils, who saw the material world as temporary and emphasized spiritual salvation beyond ecclesiastical institutions.

Medieval Bosnia is known from historical sources as one of the main centers of this heterodox Christianity. The Bosnian Church, considered heretical by Rome and Constantinople, created an environment where a special funerary culture developed, independent of the official canons. The funerary monuments of this tradition were not simply grave markers, but statements of identity and spirituality.

The claim that these monuments are “Serbian” or “Slavic” is late and unfounded in historical reality. The early Slavs did not have a tradition of monumental stone tombs with such iconography, while most of these tombs date back to before the consolidation of Slavic church structures in the region. Their appropriation occurred much later, in the context of the nationalisms of the 19th–20th centuries.

Therefore, in Albanian and scientific terminology, these monuments should be called: Medieval funerary monuments of the Cathar-Illyrian-Thracian tradition or Medieval funerary monuments of dualistic Balkan Christianity.

This designation more accurately reflects their historical, cultural and religious reality, freeing them from ideological labels and returning them to their true Balkan and pre-Slavic context.

References

Marian Wenzel, Studies in Bosnian and Herzegovinian Tombstones (Stećci), National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sarajevo, 1965–1982.

The most authoritative study on iconography and dating; links the phenomenon to local non-canonical culture, not to Slavic tradition.

Noel Malcolm, Bosnia: A Short History, Pan Macmillan, London, 1994.

– Chapters on medieval Bosnia and the Bosnian Church; confirms the heterodox character and the pre-national context.

John V. A. Fine Jr., The Bosnian Church: A New Interpretation, East European Quarterly, Boulder, 1975.

– A seminal work on the Bogomils/Cathars and the religious structure that explains the symbolism of the monuments.

Dimitri Obolensky, The Bogomils: A Study in Balkan Neo-Manichaeism, Cambridge University Press, 1948.

– A classic study of Balkan dualism, with direct relevance to medieval Bosnia.

Šefik Bešlagić, Stećci – kultura i umjetnost, Veselin Masleša, Sarajevo, 1982.

– Documents the distribution and typology; acknowledges that the phenomenon is not an ethnic Slavic creation.

Aleksandar Solovjev, Bogomilstvo i stećci, Belgrade, 1954.

– Although a Slavic author, he connects the stećaks with Bogomilism, not with the Serbian Orthodox Church.

Franjo Rački, Bogomili i Patareni, Zagreb, 1870.

– Classic source on the connection between the Western Cathars and the Balkan Bogomils.

UNESCO, Stećci – Medieval Tombstone Graveyards (World Heritage Site, 2016).

– Accepts the multi-confessional and non-ethnic character, avoiding the Slavic definition.

Florin Curta, Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

– Analyses the pre-Slavic continuity and local structures in the Balkans.