Abstract

This article examines an early twentieth-century British encyclopedic portrayal of Albania and the Albanians, rediscovered by researcher Shyqyri Nimani in an antiquarian book collection in Bournemouth. The source in question is Peoples of All Nations: Their Life Today and the Story of Their Past, edited by J. A. Hammerton and published in London by The Amalgamated Press. Within the first volume of this extensive work, Albania is presented across eighteen pages, accompanied by photographs and a map, authored primarily by Mary Edith Durham, with additional contributions by H. T. Montague Bell.

Through Nimani’s analysis, first published in the journal Albanica in 2007, the article explores how this encyclopedia constructs Albania as one of the oldest and most distinctive peoples of the Balkans. Durham’s contribution emphasizes Albanian continuity from ancient Illyrian and Celto-Illyrian origins, highlighting cultural resilience, strong national consciousness, craftsmanship, folklore, social customs, and religious coexistence. She presents Albanians as a people who consistently placed ethnic identity above religious division and who resisted cultural assimilation despite centuries of foreign domination.

Bell’s section complements this narrative by framing Albania as an emerging European state while reinforcing claims of Albanian antiquity, territorial continuity, and ethnic unity despite internal religious and regional differences. Together, these texts reflect a Western anthropological and historical discourse that portrays Albanians as a distinct, enduring Balkan people. The article argues that this encyclopedic representation is significant not only as a historical source, but also as evidence of how Albania and Albanian identity were perceived and articulated in British intellectual circles at the turn of the twentieth century.

In a collection of antiquarian books, several years ago, researcher Shyqyri Nimani came across an encyclopedic publication, among whose pages were several pages dedicated to Albania. An almost century-old publication. Nimani testifies that he came across these traces while researching among these antiquarian books in the center of the southern coastal and very beautiful English city of Bournemouth.

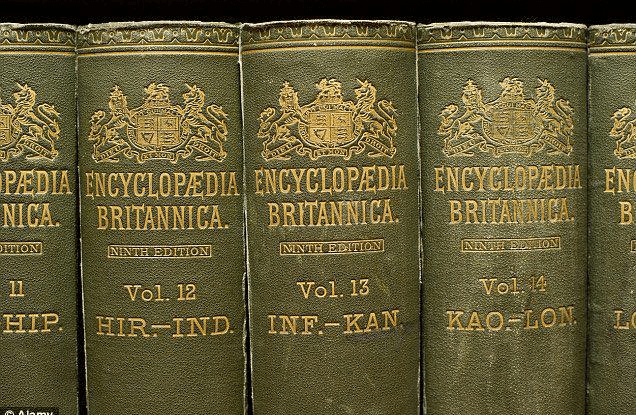

The voluminous British encyclopedia is entitled “Peoples of all nations- Their Life Today and the Story of their Past”. The texts are written by the most prominent writers of travel anthropology and history, and are illustrated with over 5,000 photographs, numerous color tables and 150 maps,

The editing was done by the well-known J.A.Hammerton, and it was published by “The Amalgameted Press Limited” in London. Nimani published the research on this case in March 2007 in the monthly “Albanica” and among other things explains details on that part of this encyclopedic volume that is directly related to Albania.

As Nimani explains, the first volume which starts from page 1 to page 78, from Abyssinia to the British Empire also includes the chapter related to Albania (Albania) starting from page 46 and ending with page 63. So, there are 18 pages, 18 photographs and 1 map, all in black and white. 15 pages were written by Mary Edith Durham, while 3 other pages by H.T.Montague Bell,

The most voluminous chapter, entitled “The oldest and most unique of the Balkan peoples” was written by M.Edith Durham, author of the book “High Albania”. Among other things, Durham writes:

“About 600 B.C. they were conquered and perhaps largely influenced by the Celts, from the north. From this Celto-Illyrian stock the modern Albanian is descended. He is thus the oldest inhabitant of the Balkan Peninsula, and the fact that he has survived the successive conquests and rule of the Romans, Bulgarians, Serbs and Turks and remained Albanian is sufficient evidence of his strong national feeling.

No conqueror has succeeded in subduing him.” Miss Durham then writes that each tribe has its own patron saint and that the festivals are celebrated in a magnificent manner. The folk costumes with all the feminine and masculine adornments create unforgettable scenes.

War has devastated these lands and left the starving population devastated, plundered successively by the Montenegrins, the Serbs, the Bulgarians and the Austrians. Albanians used the favorable periods to rebuild the burned villages and normalize their lives.

Next, Miss Durham describes the life of the citizen throughout Albania, who leads a very different life from his rural compatriot. “He is usually a skilled artisan and works industrially. Almost the entire production of beautiful gold embroidery in the Balkans is Albanian work. The magnificent costume of the Court of Montenegro was the creation of Albanian tailors.

Most of the Balkan goldsmiths, too, are Albanians or of Albanian descent. And, strangely enough—as Miss Durham says—most of the artistic formations still made by them resemble the ornaments found in prehistoric tombs, so that together skill and ornament seem to have been inherited from the ancient Illyrians. She then goes on to assert that the domestic cleanliness of the Albanian may be an example to many others.

“Churches and mosques together may be found in the larger cities. Since the Turks had conquered Albania at the end of the fifteenth century, the Albanians had for years sought help from Christian Europe and especially from Venice. No one came, and in the 18th century Islam began to spread in Albania, as it did in other Balkan lands. But Albanians put race before religion, and Christians and Muslims joined forces to fight the Turks for independence.

Nor is the Albanian Muslim fanatic”. Durham then writes about the mixed marriages of Christian and Muslim Albanians against the orders of the clergy, that members of both religions could sometimes be found in the same family. Many tribes are mixed and Christians and Muslims have the same national customs inherited from antiquity: the ora-spirit that flashes like fire at night; the witch-who can shrink to the size of a fly, who slips through a keyhole and sucks the blood of her victim.

There are villagers in Albania who can cure certain diseases and very skilled surgeons who can perform operations, because they understand antiseptic treatments. Indeed, it seems that this method was practiced in Albania before it was known in England.

According to Niman, “Durham’s focus is on the relevant data on the language of the Albanians, in which case, among other things, he writes that the Albanian language is spoken from the plains of Kosovo to the Gulf of Artës, that it is undoubtedly the language of the ancient Illyrians – the Macedonian speech of Alexander the Great.

Strabo (from the 1st century AD) told us that both peoples (Illyrians and Macedonians) spoke the same language. The Albanian, whether Christian or Muslim, feels pride in this language with a zeal and determination that contains something heroic”.

Durham further writes that the Serbs, Greeks and Turks tried in vain to destroy the Albanian language. The Serbs and Montenegrins have annexed thousands and thousands of Albanians and have never allowed them to have a school or to print a paper in their native language.

Durham writes: “since the Christian Albanians of the south belong to the Orthodox Church, a Greek bishop here once even excommunicated the Albanian language and the priests said that it was useless to pray in Albanian since Christ does not understand it. On the other hand, the Turks sentenced anyone who lectured or published in the forbidden Albanian language to fifteen years in prison.

But the steadfast Albanian published his books abroad and smuggled them in with difficulty and danger. The Albanian learned and remained Albanian. When he had the opportunity, he studied in Vienna or Paris. Many students were educated at Robert College by Americans”. Meanwhile, the second chapter on Albania was written by H.T. Montague Bell, editor of “The Near East”. He titled his article “The Rise of the Infant State of Europe”.

“Descendants of the first Aryans of the arrival and of the Illyrians, Thracians or Epirotes of classical times, the Albanians are the oldest race in Southeastern Europe. The same well-defined division, which once divided the country between the kingdoms of Illyria and Molossia, can be found today at the Shkumbin River (the Via Egnatia, the great Roman artery between East and West), separating the two main parts of the population.

But, despite the differences between them in religion, dialect and social institutions, the Albanians have always maintained a race – as a peculiarity of national consciousness and have clearly distinguished themselves from the other races of the Balkan Peninsula”. Bell then writes about the successive conquests of Albanian lands and the wars for freedom.

Then he presents facts about the country, power, trade and industries, communications, religion and education, the main cities – which had this number of inhabitants: Durrës (5000), Shkodra (32,0000), Elbasan (13,000), Tirana (12,000), Gjirokastra (12,000), Korça (8,000), Vlora (6,500). Ad.Pe.

Albanians the oldest race in Southeastern Europe H.T. Montague Bell H.T. Montague Bell, was editor of “The Near East”. From three pages written by him in the encyclopedic volume we have extracted this passage: “Descendants of the first Aryans of the Ardhacak and of the Illyrians, Thracians or Epirotes of classical times, the Albanians are the oldest race in Southeastern Europe.

The same well-defined division, which once divided the country between the kingdoms of Illyria and Molossia, can be found today at the Shkumbin River (the Via Egnatia road, the great Roman artery between East and West), separating the two main parts of the population. But, despite their differences in religion, dialect, and social institutions, the Albanians have always maintained a race—as a peculiarity of national consciousness and clearly distinguished from the other races of the Balkan Peninsula.”

The Albanians, the Oldest and Most Distinctive People of the Balkans Mary Edith Durham Throughout the eastern half of the Balkan Peninsula—in Bosnia, Serbia, Montenegro, and Albania—remains of a very early people have been found in prehistoric cemeteries. They were skilled bronze workers and were among the first in Europe to work and use iron. Their origins are lost to the past.

About 600 B.C. they were conquered and perhaps extensively influenced by the Celts from the north. From this Celto-Illyrian stock the modern Albanian is descended. He is thus the oldest inhabitant of the Balkan Peninsula, and the fact that he survived successive Roman conquests and rule, The fact that he was conquered by the Bulgarians, the Serbs and the Turks and remained Albanian, sufficiently proves his strong national feeling.

No conqueror has succeeded in subduing him. Consequently, among the Albanians we still find traces of some of the earliest European costumes. Like the Scottish Highlanders, the Albanians were a tribal people. These tribes at an early time formed two groups, under separate princes. These groups may still be defined as the Ghegs of the north and the Tosks of the south.

They are one and the same people, speaking the same Albanian language. The Ghegs, however, live in a much harsher land and in the natural fortresses of the mountains have preserved some of the old customs than the Tosks of the south. In the northern mountains the tribal system still holds its own, and in spite of oppressors and conquerors the tribes ruled themselves according to ancient unwritten laws and customs, carried over from a remote period and administered by the elders of the tribe. in the solemn council.

The northern Albanian has further demonstrated his his powerful left, in which case the great number of the fissanaks remained loyal to the Roman Catholic Church. Albania was Christianized at a very early time. Shkodra was the Bishopric of the Patriarchate of Rome several centuries before the pagan Serbs and Bulgarians were converted, and despite the oppression inflicted on them during the time when Northern Albania fell under Serbian domination in the Middle Ages, the Northern Albanians are among the very few peoples of the Balkans who steadfastly refused to join the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Churches and mosques together can be found in the largest cities. Since the Turks had conquered Albania at the end of the 15th century, the Albanians sought help from Christian Europe and especially from Venice for years. No one came, and in the 18th century Islam began to spread in Albania as it did in other Balkan lands. But Albanians put race before religion and Christians and Muslims joined forces to fight the Turks for independence. Nor is the Albanian Muslim fanatic.

Article