By Col Mehmeti. Translation Petrit Latifi

Abstract

The emergence of modern national consciousness in the Balkans was deeply influenced by intellectual currents originating in the German-speaking world. German Romanticism, articulated by figures such as Goethe and the Brothers Grimm, promoted a model of nation-building rooted in language, folklore, and shared cultural memory. This model was adopted by South Slavic intellectuals, most notably Vuk Karadžić, who encountered these ideas in Vienna and applied them to the Serbian context. Folklore collection became a foundational nationalist practice.

Karadžić’s Srpski rječnik (1818), the first dictionary of modern Serbian, reflects this early, Herderian phase of nationalism. Containing approximately 26,000 entries with German and Latin explanations, the dictionary also includes references to Albanian spaces and populations. Notably, the city of Peja (Ipek) is described as being located in Albania. However, in the revised 1852 edition, the same city is reclassified as part of “Old Serbia,” revealing a significant conceptual shift.

This article examines how such a geographical redefinition became possible and what it reveals about the transformation of nationalist thought. It argues that the change reflects the transition from a pluralistic, culture-centered Romantic nationalism to an expansionist, state-driven nationalism. While Albania initially appeared as a neutral cultural designation, it later became incompatible with emerging territorial ambitions. Yet the concept of Albania proved resilient, continuing to appear in the political and cultural discourse of the autonomous Serbian state.

The awareness of something originally called Albanian was born in a laboratory of innovative ideas in the German world. German Romanticism, with colossuses like the poet Goethe or the Brothers Grimm, spread a recipe that, if followed meticulously, could give birth to an immortal creature like the nation.

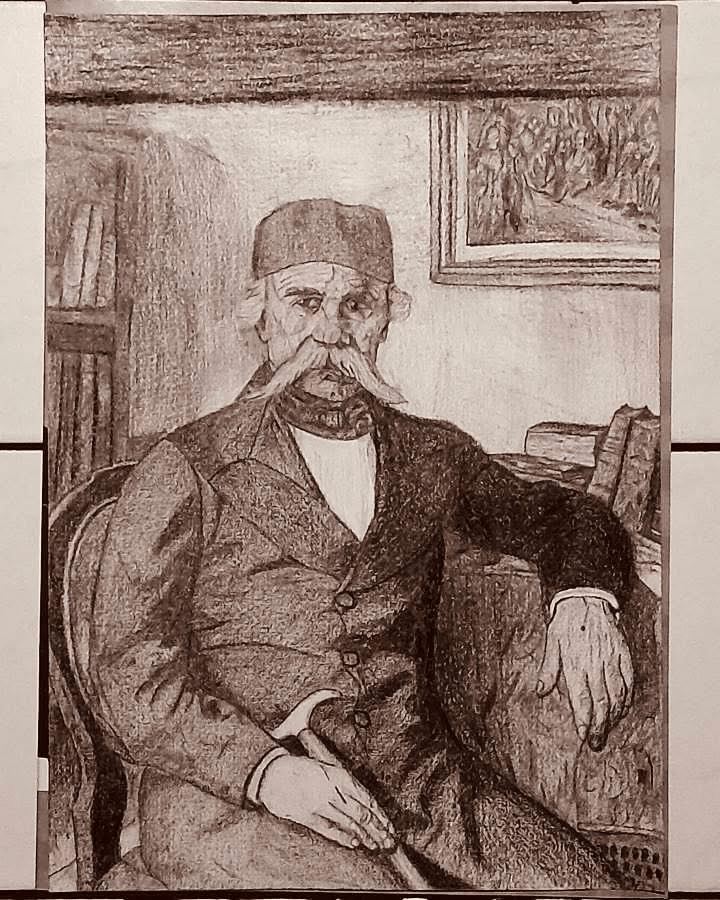

Having learned this recipe in Vienna, Vuk Karadžić wanted to try it among his own people and suddenly a new consciousness opened his eyes among the people. It was the time of nationalism and the collection of folklore was considered the first rite.

In 1818, Karadžić published the first dictionary in modern Serbian “Srpski rječnik”, which included 26 thousand words with explanations in German and Latin. There are also some Albanian pieces that found a place in the dictionary.

For example, the Peja of the Kelmends and Begolls was listed as being located in Albania: “Die Stadt Ipek in Albanien” (p. 551) 34 years later when he reprinted the same dictionary, Karadžić rounded up the content in places. In the section on Peja, he revised it and wrote: “Die Stadt Ipek in Alt-Serbien” (p. 497)

How was it possible for a city to be located in two places at the same time?

Which place was real and which imaginary, which on earth and which only in books?

In the first case, in 1818, Karadžić was the ‘Herderian’ nationalist who saw the world as a flower garden. The flowers are the nations that are not pushed by borders and lands, but are happy with their differences.

In the second case, in 1852, Karadžić was already old. His students were grown.

Many of them were leaders of the autonomous state and no longer looked down on the former projects of collecting fairy tales and folklore.

Now, the nationalist idea sought expansion, it sought with a hungry eye new spaces.

Albania, which in 1818 was mentioned without any intention or harm, in 1852 was somewhat of an obstacle, so it had to be replaced with something else. This is how it was called “Old Serbia” because it coincided with a new vision.

But, an idea is hard to throw away that can be reversed even if a correction is made. Albanian had also found a place in the discourse of the autonomous Serbian state itself. Perhaps as a natural inertia, newspapers, pamphlets, and books of the Obrenović dynasty used the concept of Albania as the first southern neighbor.

Reference

Srpski rječnik (Српски рјечник), Vuk Karadžić, 1818.