by Bekë Vuçetaj. Translation Petrit Latifi

Abstract

The men of the Buçaj tribe had long joined the freedom fighters, while the women and children sought refuge far from the routes of Montenegrin attacks. One woman, however, refused to abandon her home and her few belongings: Kaje Gala Selmani. When Montenegrin troops suddenly entered the village, the roads were cut off, preventing her from reuniting with other family members.

As she moved toward the tower, Sadri Groshi, an 85-year-old man, entered her courtyard. Fearing he would bring danger, she whispered to herself but took him by the arm and led him inside. She locked the tower door and climbed to the second floor. There, she took up a rifle and began resisting from the tower’s loopholes. With only a few bullets but a strong defensive position, each shot found its target. While Kaja fired from one opening to another, Sadri shouted loudly to deceive the attackers, calling for reinforcements.

When the ammunition ran out, the Montenegrins broke down the door and stormed the tower. Kaja pulled Sadri behind the door, seized an axe, and hid. The first soldier entered—she struck and decapitated him. The second, third, and fourth followed, meeting the same fate. Only after the soldiers withdrew did Sadri emerge, finding the tower covered in blood and Kaja wounded, yet unbroken.

Her act became a symbol of resistance—of defending freedom, homeland, and the threshold of one’s house. Among the people of Nokshiq, her heroism is still spoken of as an example of Albanian tradition and honor. Following the defeat of the Montenegrin forces—who reportedly left over 300 dead—Prince Nikola was forced to request a ceasefire from the League forces in Plav and Guci.

The Buçaj family continued to defend Albania’s territorial integrity through the upheavals following 1912. After 1913, they faced immense pressure: forced assimilation, religious coercion, population displacement, and violence. Yet resistance continued. In 1918, the family again took up arms against Montenegrin forces, becoming a formidable obstacle to occupation.

Kaja fought not alone but alongside her children. Her sons and daughters—Zymer, Ymer, Begeja, and Lacja—became legendary figures of resistance. Begeja, even after her brothers fell, continued to fight, earning respect across the region. She wore men’s clothing, carried a rifle, and rejected domestic expectations, declaring she knew only one craft: war.

Begeja and her husband Bajram Isufi fought together across Rugova, Plav, Guci, Nokshiq, and beyond, alongside notable resistance figures such as Shotë and Azem Galica. Known for her horsemanship and courage, she became a living emblem of defiance.

The family’s suffering continued into the mid-20th century. Ymer Maliqi, Kaja’s son, resisted Yugoslav communist reoccupation until 1946, when he was killed by poisoning through betrayal. His remains were reburied in Peja in 2010 after local authorities refused to allow a memorial at his birthplace.

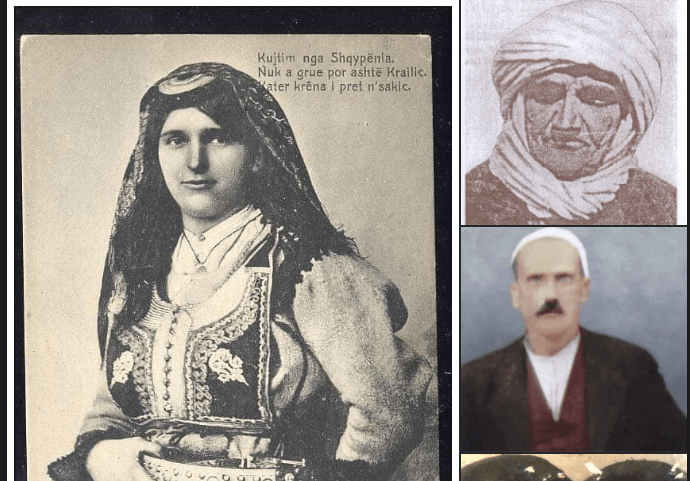

Kaja Gala Selmani lived nearly a century. Tall, dignified, deeply respected, she never removed her weapons and treasured above all the Silver Medallion awarded to her by Sylejman Aga Vokshi for bravery. Though the medallion later disappeared under mysterious circumstances, her legacy endured.

In 1993, the Buçaj family received two first-class decorations for bravery from the President of Albania: one for Kaje Gala Selmani, and one for her son Ymer Maliqi—a final recognition of a family whose history was written in sacrifice, resistance, and unwavering devotion to Albania.

The Heroism of Kaje Gala Selmani and the Buçaj Family

The men of the Buçaj tribe had long since joined the freedom fighters, while the women and children had taken refuge in places more or less distant from the routes of Montenegrin attacks. However, one Albanian woman, Kaje Gala Selmani, refused to leave her home and her few possessions. Suddenly, Montenegrin troops entered the village, and all paths were cut off, making it impossible for her to reunite with her relatives or other villagers.

As she headed toward the family tower, Sadri Groshi, an eighty-five-year-old man, entered the courtyard. “You too, may God protect you,” Kaje whispered to herself, fearing that his presence would bring her trouble. Nevertheless, she took him by the arm and led him into the tower, locking the door behind them.

She climbed to the second floor, took out a rifle, and began resisting from the tower’s loopholes. They had only a few bullets, but their position was ideal—one bullet for one Montenegrin. While Kaje fired from one side and then the other, Sadri’s task was to shout as loudly as possible, calling out: “Hold on, Maliqi’s men are coming!”

When the bullets ran out, the Montenegrins broke down the tower door and rushed toward the upper floor. Kaje, determined to resist until the very end, pulled Sadri behind the door, seized an axe, and hid. The first soldier entered and Kaje struck him with the axe, beheading him. The second entered, then the third, then the fourth—each met the same fate.

After the Montenegrin soldiers withdrew, Sadri emerged and found the room drenched in blood. He then noticed that Kaje herself was wounded, yet she had not given up. As he tried to bandage her wound, he cried out in fear:

“Where were you hit, sister? The blood is pouring out as if you were stabbed!”

Kaje calmly replied, as if nothing had happened: “Here.”

Sadri took her by the hand and helped her climb to the top of the tower. There he saw Montenegrin soldiers lying stretched out, their heads severed and crushed, immersed in their own blood.

Kaje’s heroic act became a lasting inspiration for defending freedom, homeland, and the threshold of one’s home. This is how the people of Nokshiq have spoken—and still speak—about the heroism of this daughter of Rugova. According to Albanian tradition, Kaje earned the honor of standing beside the bravest men, those who had proven themselves through bloodshed in battle.

After the defeat of the so-called invincible Montenegrin army—as Prince Nikola liked to describe it—leaving more than three hundred dead on the battlefield, he was forced to request a ceasefire from the League forces in Plav and Guci.

The later historical fate of these lands is well known, unfolding through and beyond the raising of the Albanian flag in Vlora in 1912. The Buçaj family, rifles in hand, with men, women, and youth, stood ready whenever Albania’s territorial integrity was threatened.

After 1913, socio-political conditions turned against the Albanian population of the region. They faced pressure to change religion and nationality, forced demographic changes, and eventually mass displacement, especially after the 1950s. This family, however, was never separated from suffering and tragedy.

In 1918, the family again rose in arms against the Montenegrins, determined to become masters of their homeland and trampled freedom. They stood firm like a rock against storms and winds, never yielding. Their resistance made them an insurmountable obstacle to Montenegrin chauvinism, which sought their elimination at any cost.

To destroy them, Montenegrin soldiers surrounded the family at night, believing that their defeat would open the way to the evacuation of Nokshiq and the surrounding area. The family’s resistance, like the “good hour” of the mountains, was immortalized in folk verses.

The mother, together with her daughters Begeja and Lacja, and her sons Zymer and Ymer, stood surrounded in a struggle for life or death. The main cause of the tragedies suffered by this family—and many others—lay in the conspiracies of European diplomacy in collaboration with Pan-Slavic circles against the Albanian people.

Being a Nokshiqan meant living in constant vigilance. One always had to stand guard, rifle in hand, never knowing when danger would strike. According to field notes, the local population constantly defended their lands against Montenegrin Chetnik hordes and gangs.

The heroism of Kaje Gala Selmani, as the central figure of this narrative, becomes even more powerful when viewed as part of collective family resistance. The siege remembered in song dates back to 1918, when her son Zymer was killed. Once again, she fought from the tower—this time alongside her sons and daughters.

For these acts of bravery, Sylejman Aga Vokshi, Commander-in-Chief of the All-Albanian Resistance, awarded her a Silver Medallion in the Highlands of Gjakova, as gratitude to an Albanian woman who placed her children in the service of the homeland.

Kaje was first married to Gali Rexhi of the Buçaj tribe, who was killed in the Nokshiq war. According to tradition, she was later married within the same family to Maliqi, who was also killed early in the struggle against the Montenegrins. From Maliqi’s first marriage came four sons—Jahe, Syle, Delina, and Ali—all killed in ambushes and continuous fighting between 1913 and 1946. None lived beyond the age of twenty-three, except Delina, who left behind a single daughter, Xhemile.

From Maliqi’s marriage to Kaje were born Zymer, Ymer, Lacja, and Begeja. Alongside their parents, these four became legendary defenders of the homeland, continuing the family’s tradition of courage and sacrifice.

Begeja, even after her brother fell on the battlefield, continued fighting against Montenegrin soldiers, forcing them to flee and preserving the honor of Nokshiq. Since 1918, alongside her mother Kaje, her brothers Ymer and Zymer, her husband Bajram Isufi of Kuqishta, and other kaçaks, she stood on the front lines of resistance.

She rejected traditional domestic roles, declaring: “I know neither needle nor thread, fork nor spindle—I know only this,” pointing to the Mauser rifle hanging on the wall.

Always dressed in men’s clothing, she was proud of it. She never tried to beautify herself. When her sisters-in-law tried to apply makeup on her wedding day, she silently turned away. An old woman finally said: “Do not worry, this is Bege Maliqi—she does not need red or white.”

She was a master horsewoman. On her wedding journey, when her escort lost control of the horse, Begeja seized the reins and rode ahead alone. When the wedding party arrived, they found her calmly waiting, greeting them with irony: “Besa, you were not very late.”

Begeja left behind two sons, Adem and Bajram, and a daughter. Adem lived until the last war in Kosovo, during which paramilitaries killed four members of his family—his wife, son, daughter, and one-year-old grandson. The same fate that had struck previous generations returned once again.

Begeja rests today in the village cemetery. Her grave, forgotten by people, is remembered only by mountain birds. No monument marked her sacrifice until recently.

Her brother Ymer Maliqi continued resisting Yugoslav communist reoccupation. He lived in caves in Valbona and Dragobi with his son Zymer and grandson Shaqiri. In 1946, through betrayal, he was poisoned. His death shook all of Rugova.

His remains were later reburied in Peja in 2010, where he was honored with a large ceremony. Telegrams were read, including one declaring his lifelong devotion to Albania and the sacrifices of the Buçaj family.

Kaje Gala Selmani lived nearly a hundred years. Tall, dignified, deeply respected, she never removed her weapons and treasured above all the Silver Medallion awarded for her bravery. Though the medallion later disappeared under mysterious circumstances, her legacy endures.

In 1993, the Buçaj family received two first-class decorations for bravery and patriotic service from the President of the Republic of Albania—one for Kaje Gala Selmani and one for her son Ymer Maliqi.