Narcissism and Sociopathy in Serbian society: A review of empirical research of mental health

Abstract

This article examines the intersection of right-wing extremism, Chetnik ideology, and war crime perpetration in the Serbian context through the lens of personality psychology and collective processes. Drawing on social-psychological theories of collective narcissism and research on narcissistic and antisocial personality traits, the analysis explores how ethno-nationalist ideologies have contributed to intergroup hostility, moral disengagement, and the legitimization of violence against Albanians, Bosniaks, and Croats. The review situates contemporary neo-Chetnik extremism within broader patterns of collective narcissism, characterized by exaggerated in-group glorification, historical grievance narratives, and hypersensitivity to perceived external threats.

Additionally, the article integrates findings from perpetrator psychology and international criminal justice to contextualize war crimes committed by individuals associated with Serbian political, military, and paramilitary structures during the Yugoslav wars. While emphasizing individual criminal responsibility, the analysis highlights how narcissistic grandiosity, callous-unemotional traits, and antisocial dynamics—when embedded in authoritarian and extremist environments—can facilitate mass violence. The persistence of denial and heroization of convicted war criminals is discussed as a manifestation of collective narcissism with significant implications for mental health, reconciliation, and post-conflict societal recovery

Keywords: Narcissism, Sociopathy, Psychopathy, Dark Triad, Mental Health, Serbi

Introduction

Narcissism and sociopathy represent complex personality constructs that occupy a contested space between adaptive traits and psychopathology. Narcissism ranges from subclinical personality features to Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD), while sociopathy is commonly conceptualized within the framework of Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD) or psychopathy (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

In post-socialist societies such as Serbia, rapid social change, economic instability, and prolonged exposure to collective stressors (e.g., war, sanctions, and transition-related uncertainty) have prompted interest in how maladaptive personality traits manifest within the population. Serbian psychological research has increasingly addressed these traits, particularly through dimensional models such as the Dark Triad and Dark Tetrad.

Orthodox Fundamentalism, Chetnik Ideology, and Collective Narcissism in Serbian Society

Background

Chetnik ideology originates from Serbian nationalist movements of the early 20th century and was revitalized during the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s. Contemporary neo-Chetnik movements combine ethno-nationalism, historical revisionism, Orthodox religious symbolism, and irredentist claims, particularly toward territories associated with Albanians (Kosovo), Bosniaks (Bosnia and Herzegovina), and Croats (Croatia).

While not representative of Serbian society as a whole, these movements remain visible in political discourse, commemorative practices, and extremist subcultures (Bieber, 2018).

Collective Narcissism and Ethno-Nationalism

Recent social-psychological research distinguishes individual narcissism from collective narcissism, defined as an inflated belief in the greatness of one’s in-group coupled with hypersensitivity to perceived threats or insults (Golec de Zavala et al., 2009).

Studies conducted in the Western Balkans suggest that Serbian ethno-nationalist narratives frequently reflect collective narcissistic patterns:

- Idealization of the Serbian nation as historically heroic and victimized

- Externalization of blame onto ethnic out-groups

- Hostility toward reconciliation initiatives and minority rights

Collective narcissism has been empirically linked to:

- Intergroup hostility

- Support for political violence

- Reduced empathy toward ethnic out-groups

(Golec de Zavala et al., 2016)

Racism, Dehumanization, and Sociopathy-Related Traits

Ethnic hostility toward Albanians, Bosniaks, and Croats in extremist Serbian discourse often involves dehumanizing language, conspiracy narratives, and moral disengagement. These features overlap conceptually with callous-unemotional traits and subclinical psychopathy, particularly at the group level.

While no Serbian studies directly diagnose sociopathy within extremist groups, research on political extremism indicates that:

- Individuals high in psychopathy and narcissism are overrepresented in radical nationalist movements

- Dark Triad traits predict endorsement of authoritarianism and ethnic exclusion

(Forsyth et al., 2020; Hodson et al., 2009)

Serbian studies on the Dark Tetrad have shown that psychopathy and narcissism are associated with reduced empathy and increased aggression, especially under perceived threat—conditions frequently invoked in nationalist rhetoric (Međedović & Petrović, 2022).

Irredentism, Trauma, and Post-Conflict Identity

Irredentist attitudes toward Kosovo, Republika Srpska, and parts of Croatia persist in segments of Serbian society and are often justified through historical trauma narratives. Psychological research on post-conflict societies suggests that unresolved collective trauma can facilitate:

- Authoritarian attitudes

- Rigid in-group/out-group boundaries

- Endorsement of violence as moral restitution

(Volkan, 2001)

In Serbia, war memory, NATO bombing (1999), and perceived international injustice have been shown to reinforce grievance-based identities, which may interact with narcissistic and antisocial traits to sustain extremist worldviews (Subotić, 2019).

Implications

From a mental health perspective, extremist ideologies are not mental disorders per se. However, empirical research suggests that maladaptive personality traits, emotional dysregulation, and identity fragility increase vulnerability to radicalization.

In Serbian samples, Dark Triad traits correlate with:

- Psychological distress

- Hostility

- Poor emotional regulation

(Kostić et al., 2021)

These traits may be amplified in ideological environments that reward aggression, dominance, and moral absolutism.

War Crimes, Perpetrator Psychology, and Narcissistic–Antisocial Dynamics in the Serbian Context

Legal and Historical Context

International and domestic courts have established that war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide were committed by individuals and organized groups associated with Serbian political and military structures during the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s. The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) convicted numerous Serbian political leaders, military officers, and paramilitary commanders for atrocities committed in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Kosovo, including ethnic cleansing, mass atrocities, forced displacement, sexual violence, and genocide (ICTY, 2017).

It is crucial to emphasize that criminal responsibility is individual, not collective. However, social-psychological analysis remains necessary to understand how such crimes became possible and were socially legitimized.

Personality Traits and War Crime Perpetration

Research in perpetrator psychology consistently shows that war crimes are not committed exclusively by clinically disordered individuals. Nonetheless, certain personality traits are disproportionately represented among perpetrators and facilitators of mass violence:

- Narcissistic grandiosity and entitlement

- Callous-unemotional traits

- Moral disengagement

- Reduced empathy

- Authoritarian aggression

These traits overlap significantly with subclinical psychopathy and malignant narcissism (Baumeister et al., 1996; Miller et al., 2011).

Although Serbian-specific clinical profiling of convicted war criminals is limited, comparative research on genocide perpetrators (e.g., Nazi Germany, Rwanda, Bosnia) suggests that leaders and paramilitary commanders often display elevated narcissistic and antisocial traits, while lower-level perpetrators act under coercion, conformity, or ideological pressure (Waller, 2007).

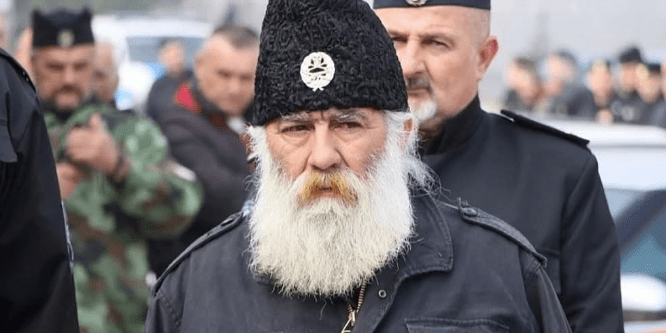

Paramilitarism, Chetnik Symbolism, and Sociopathy

Serbian paramilitary formations such as Arkan’s Tigers and various Chetnik-aligned units operated with weak institutional control and strong ideological reinforcement. These environments fostered:

- Reward structures for violence

- Dehumanization of ethnic out-groups

- Group norms suppressing empathy

- Celebration of cruelty as patriotism

Psychological research indicates that such conditions amplify latent antisocial traits, particularly among individuals high in psychopathy or narcissistic dominance (Zimbardo, 2007).

Notably, Serbian post-war glorification of convicted war criminals through murals, public gatherings, and media narratives may reinforce collective moral disengagement, normalizing antisocial behavior and undermining mental health at the societal level.

Denial, Heroization, and Collective Narcissism

One of the most distinctive features of the Serbian post-conflict context is the persistent denial or relativization of war crimes, including the genocide in Srebrenica, despite international legal judgments.

Collective narcissism theory provides a robust explanatory framework:

- In-group greatness is perceived as unquestionable

- Acknowledgment of crimes is experienced as an existential threat

- Perpetrators are reframed as heroes or martyrs

- Victims are delegitimized or blamed

Empirical studies show that collective narcissism predicts:

- Hostility toward out-groups

- Rejection of historical responsibility

- Support for violent political rhetoric

(Golec de Zavala et al., 2019)

In Serbia, these mechanisms have been documented in public discourse, education, and political messaging (Subotić, 2019; Bieber, 2018).

Mental Health Consequences

The societal handling of war crimes has significant mental health implications:

- For victims and survivors: prolonged trauma, PTSD, intergenerational transmission of suffering.

- For perpetrators: high rates of PTSD, substance abuse, emotional numbing, and antisocial behavior.

- For society: normalization of aggression, distrust, and impaired reconciliation.

Studies of Balkan veterans indicate elevated psychological distress, particularly among individuals with pre-existing antisocial traits (Kovačević et al., 2014). Failure to confront crimes openly has been linked to collective psychological stagnation, reinforcing grievance-based identities and extremist ideologies.

Synthesis: From Individual Pathology to Societal Harm

The case of Serbian war crimes illustrates how individual narcissistic and sociopathic traits, when embedded in authoritarian structures, nationalist ideology, and collective narcissism, can culminate in large-scale human rights violations. While most individuals do not possess pathological traits, systems that reward dominance, dehumanization, and denial enable those traits to exert disproportionate influence.

From a mental health and prevention perspective, confronting historical crimes is not merely a moral imperative but a psychological necessity for reducing future violence.

Discussion

The analysis of right-wing extremism, Chetnik ideology, and war crime perpetration in the Serbian context reveals a convergent set of psychological and socio-political mechanisms that link individual personality traits with collective ideological processes. Rather than attributing violence or extremism to psychopathology alone, the findings underscore how narcissistic and antisocial traits can become socially amplified within nationalist and authoritarian environments, producing outcomes with severe human and psychological consequences.

A central contribution of this discussion is the integration of collective narcissism as a bridging construct between individual-level traits and large-scale political violence. Collective narcissism helps explain why ethno-nationalist ideologies rooted in Chetnik symbolism remain resilient despite legal judgments, historical evidence, and international condemnation. The persistent glorification of national victimhood, combined with hypersensitivity to perceived external humiliation, creates a psychological climate in which acknowledgment of war crimes is experienced not as moral reckoning but as an existential threat to group identity. This defensive posture facilitates denial, minimization, or heroization of convicted war criminals, thereby sustaining intergroup hostility and obstructing reconciliation.

The discussion of war crime perpetration further illustrates that mass violence does not require a population of clinically disordered individuals. Instead, it emerges from the interaction between situational pressures, ideological legitimation, and a subset of actors displaying elevated narcissistic, psychopathic, or callous-unemotional traits. Leadership figures and paramilitary commanders—who often occupy positions that reward dominance, lack of empathy, and grandiosity—are particularly likely to translate these traits into organized violence. At the same time, lower-level perpetrators may act under conformity, fear, or moral disengagement, highlighting the importance of structural and cultural factors over purely individual pathology.

Importantly, the Serbian case demonstrates how post-conflict denial and revisionism function as psychologically maladaptive coping strategies at the societal level. While such narratives may temporarily protect collective self-esteem, they appear to perpetuate long-term psychological harm by freezing societies in grievance-based identities. This dynamic has implications for mental health beyond ethnic relations, contributing to normalized aggression, distrust in institutions, and reduced capacity for empathy within the broader social fabric.

The intersection between extremist ideology and personality traits also raises important ethical and methodological considerations. Pathologizing nationalism or entire populations would be both scientifically invalid and morally problematic. The evidence instead supports a diathesis–stress model, in which latent narcissistic and antisocial traits become behaviorally salient under conditions of ideological radicalization, social instability, and moral permissiveness. This framework allows for critical analysis without collective blame and aligns with international standards in political psychology and trauma research.

Finally, the findings suggest that addressing the psychological legacy of war crimes and extremism requires more than legal accountability alone. While international tribunals establish individual responsibility, psychological reckoning at the societal level—including education, memorialization, and public acknowledgment of victim suffering—is essential for reducing the appeal of extremist ideologies. Without such processes, collective narcissism and moral disengagement may continue to provide fertile ground for the re-emergence of ethnically motivated hostility and political violence.

In sum, the Serbian case illustrates how narcissistic–antisocial dynamics, when embedded in right-wing extremist ideology and reinforced through denial of past crimes, can exert enduring effects on mental health, intergroup relations, and democratic development. Future research should adopt interdisciplinary approaches combining clinical psychology, social psychology, and political science to better understand—and ultimately mitigate—these dynamics in post-conflict societies.

References

Forsyth, D. R., Banks, G. C., & McDaniel, M. A. (2020). A meta-analysis of the Dark Triad and unethical behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 167(3), 495–514.

Golec de Zavala, A., Cichocka, A., Eidelson, R., & Jayawickreme, N. (2009). Collective narcissism and its social consequences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 1074–1096.

Golec de Zavala, A., Dyduch-Hazar, K., & Lantos, D. (2019). Collective narcissism: Political consequences of investing self-worth in the ingroup’s image. Advances in Political Psychology, 40(S1), 37–74.

Hodson, G., Hogg, S. M., & MacInnis, C. C. (2009). The role of personality in prejudice. Journal of Personality, 77(6), 1749–1784.

Međedović, J., & Petrović, B. (2022). Dark Tetrad traits and psychological distress among violent offenders and community adults in Serbia. Primenjena Psihologija, 15(1), 27–45.

Volkan, V. D. (2001). Transgenerational transmissions and chosen traumas. Group Analysis, 34(1), 79–97.

Baumeister, R. F., Smart, L., & Boden, J. M. (1996). Relation of threatened egotism to violence and aggression. Psychological Review, 103(1), 5–33.

Bieber, F. (2018). The rise of authoritarianism in the Western Balkans. Palgrave Macmillan.

ICTY. (2017). Key judgments and cases. International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

Miller, J. D., Hyatt, C. S., & Campbell, W. K. (2011). Narcissistic personality disorder and antisocial behavior. Journal of Personality Disorders, 25(2), 168–185.

Subotić, J. (2019). Yellow star, red star: Holocaust remembrance after communism. Cornell University Press.

Waller, J. (2007). Becoming evil: How ordinary people commit genocide and mass killing. Oxford University Press.

Zimbardo, P. (2007). The Lucifer effect: Understanding how good people turn evil. Random House.