by Shefqet Cakiqi-Llapashtica. Translation Petrit Latifi

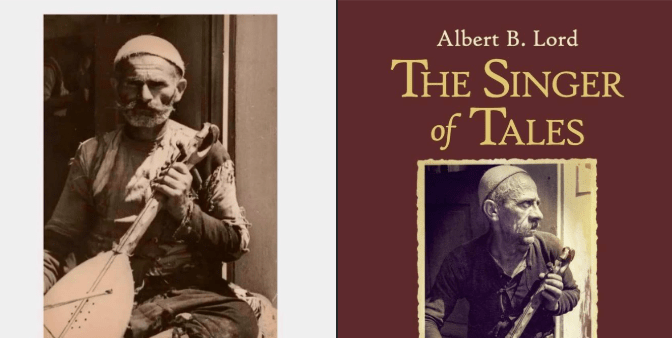

Under the Shadow of Myth: Sheq Kolaj and the Legacy of an Oral World. In the summer of 1932, in the town of Bijelo Polje in northern Montenegro, sat a man in old, worn clothes. In his hand he held an ancient Balkan instrument – the lute (Lahuta).

The lines on his face bore the marks of stories, not of years. That man’s name was Sheq Kolaj. That day, Milman Parry, a young linguist from Harvard University, encountered Kolaj during his research trip to the Balkans. Parry was traveling from one village to another, documenting the local oral tradition. His goal was to record epic tales, which lived in the language of the people through the ozans (lute players).

He took a picture – and it remained a silent witness to a culture.

One string, thousands of stories

A single-stringed bowed instrument, used for centuries by Albanian, Montenegrin and Bosnian lute players. Each lute carries within it the echo of the mountains, the struggle of the people and unforgettable heroism. Legends like Sheq Kolaj told legends through music, keeping the memory of their people alive.

Each performance was much more than a song – it was a history lesson, a declaration of identity. The voice of the lute was not just a melodic voice – it was also a form of resistance. A way of remembering in the face of poverty, war and oblivion.

Milman Parry’s legacy

This fieldwork by Milman Parry in the Balkans during the 1930s laid the foundations for the modern study of oral literature. Parry discovered how spoken poetry was improvised and passed down from generation to generation through the recordings he collected from public rhapsodists like Sheq Kolaj.

This approach, now known as the “Parry-Lord Theory,” enabled us to understand an oral cultural chain that stretches from the legends of Homer to the lute players of the Balkans. But, above all, that photograph from Parry’s lens says something more than words: The silent pride of an ozan.

More than a photograph

Today, this black-and-white photograph is preserved in the Harvard University Archives. But if you look closely, you can still hear the same voice:

A lute string vibrating, a vision of myth and a folk memory.

Although that moment has long passed, the story of Sheq Kolaj continues to be told, as does the sound of his lullaby.

Sources:

Milman Parry Oral Literature Collection, Harvard University, Balkan Ethnomusicology Archive, Alan Dundes, Oral Tradition and Epic in the Balkans, Kicking Homer to the Curb: The American Scholar Who Upended the Classics”: By Robert Cioffi. “Hearing Homer’s Song: The Short Life and Great Idea of Milman Parry” By Robert Kanigel.

When he died in a Los Angeles hotel in 1935 — just 33 years old, fatally wounded by his own gun — classicist Milman Parry had achieved more than academics twice his age could have dreamed of.

The son of a pharmacist from Oakland, California, Parry, who had won a place at Harvard University who, at the age of 27, managed to completely revolutionize the study of Homer’s “Iliad” and “Odyssey,” showing that these epics were not written, as had long been believed, but oral — created in the act of interpretation. Almost a century after his death, he is still known as the “Darwin of Homeric studies.”

His work had far-reaching consequences, bringing orality to the center of modern culture, which today appears in everything from professional storytellers to TED Talks, podcasts, and audiobooks. In “Hearing Homer’s Song,” biographer Robert Kanigel offers the first full account of Parry’s short life, his mysterious death, and the lasting influence he left behind.

The Discovery That Changed Everything

Homer has been called a “classic” since the 5th century BC, but his poems and the identity of the person who composed them have always been a mystery. Who was Homer? How did he compose his poems? Were the “Iliad” and the “Odyssey” the works of the same man? After more than two millennia of debate, Parry has shown that these are the wrong questions.

According to him, there was no ancient poet named “Homer.”

Nor were the poems attributed to him written by a single individual; rather, they were the product of a centuries-old tradition of poet-performers.

From libraries on the Balkan terrain

Parry’s research, which had until then been conducted mainly in the libraries of Berkeley, Paris, and Cambridge (Massachusetts), took a bold turn when he traveled for 15 months in what was then the former Yugoslavia, where he discovered the Lute Singers — or “story singers,” as he later called them — who still kept alive a genuine oral tradition.

Their songs about weddings and wars, performed in coffeehouses (and later in a mobile studio built by Parry himself), offered living testimony to the and his theory of how the Homeric epics were composed was entirely possible in practice.

During his fieldwork, he created a new recording device that allowed the recording of long songs on aluminum discs—which are now preserved at Harvard University. This fieldwork marked, according to many scholars, the beginning of the modern discipline of “sound studies,” showing that poetry could be both song and epic, a living performance.

An inaccessible man even for biography

Despite his great influence—and a vast archive—Parry remains a difficult subject for biography, both for Kanigeli and for me. His collected manuscripts run to nearly 500 pages, while the recordings and transcripts he made number thousands. However, his writings rarely stray beyond technical topics; in interviews with singers, he often let his assistant do the talking.

In Kanigel’s hands, we see Parry laughing at a student performance of a Greek tragedy at Harvard, complaining about bedbugs, and driving his mud-covered Ford through the backstreets of the Balkans. But his inner life, the source of his scientific passion—even why he loved Greek epic so much—remain a mystery to both the reader and the biographer.

The person who emerges most clearly in “Hearing Homer’s Song” is his wife, Marian, who financed his doctorate and cared for his children while suspecting infidelity, moving the family back and forth across the Atlantic, and postponing her return to school. Yet even to him, Parry remained ambiguous, withdrawn, distant.

Parry’s Mysterious Death

Marian was the only witness to Parry’s death — the circumstances of which remain shrouded in mystery to this day. Kanigel provides the most detailed account yet. The police ruled the killing an accident, but another rumor quickly spread in academic circles: that it was suicide. Others suspected that he had killed Marian himself.

What is certain is the great irony that remains: The scholar who gave the world the importance of oral epic left so little of his own voice behind.

His intellectual legacy lies not in any single major work, but in a series of ideas, recordings, and notes, later developed and debated by his student and assistant, Albert Lord, and by his son, Adam Parry.

A Literature Without an Author, but with a Thousand Voices

In his work, Parry envisioned a literary form that was both profoundly traditional and strangely modern — created not by a single genius standing at the head of the Western canon, but by hundreds, perhaps thousands, of performers on stages large and small, composing and reworking songs for their audiences.

If he himself resists biography, perhaps that is entirely appropriate:

a man who gave voice to the oral tradition remains himself an undiscovered voice in history.”

Robert Cioffi, Assistant Professor of Classics at Bard College. Source:

Robert Kanigel, “Hearing Homer’s Song: The Brief Life and Big Idea of Milman Parry”.