A study by Artur Vrekaj. Translation Petrit Latifi

Published first on Thursday, 03.20.2014, 07:33 a.m. (GMT+1)

Abstract

This study examines the figure of Scamander (Helenus), a Trojan prince and son of Priam, emphasizing his role after the fall of Troy as a ruler in Epirus and founder of key centers such as Butrint and Chaonia. Drawing on Homeric epic, later classical authors (Virgil, Apollodorus, Pausanias, Strabo), and modern scholarship, the article traces Scamander’s prophetic authority, political leadership, and cultural significance. It argues that the traditions connecting Troy, Epirus, and the Pelasgian–Dardanian world reflect enduring memories of post-Trojan War migrations and the transmission of religious, political, and toponymic traditions in the western Balkans.

Scamander – The Dardanian Prince and King of Chaonia and Lower Albania

The Dardanians of Troy preserved the ancient custom of the tribes of Dardania (Illyria), from which they had come, of giving children names that recalled mountains, settlements, heroes of their lands, rivers, or even the names of the gods, invoked in their inherited Pelasgian language.

Whenever we speak of the Trojan War, our thoughts turn to Scamander (Helenus), the only Trojan prince who survived and reigned in Epirus, in Lower Albania. In Troy, one of the rivers near which the Dardanian migrants settled in Asia Minor was called Scamander, which according to the Albanian (Pelasgian) language signifies a man who no longer has dreams. The Scamander River was also called the river of the god, a son of Zeus.

According to the archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann, we learn more about this river, which he verified at Troy based also on Homer’s epic poem, the Iliad:

“Here (on Mount Gargarus) a grove and an altar were sacred to Zeus. And when Scamander is defined as the son of Zeus, where else should his sources be but on Mount Gargarus? In the imagination of the poet the river and the river of the god merge into a single personality, and the origin of both is referred, as it was, to the great father-god on Mount Gargarus.”¹

“Scamander flowed into the Hellespont (the Dardanelles), in an eastern direction…”²

Thus, after the name of the divine river, the prince Scamander was also called—known in scholarly writings as Helenus. He was the son of Priam and Hecuba, king and queen of Troy in Asia Minor. Scamander was the twin brother of Cassandra, who was a priestess in the cult of Apollo at Troy. Curiously, the most trusted figure for religious consultations among the Dardanians, and even among the heroes of the Trojan War—both brothers and opponents—was Scamander.

“One tradition says that the original name of Helenus was Scamander (Scamandrius), and that he took the name Helenus from a Thracian soothsayer, who also instructed him in the prophetic art.”³

Scamander is described by Homer in the Iliad as a “lord and warrior.”⁴

Throughout the ten-year Trojan War, Scamander was one of the four captains who fought outside the walls of Troy, together with his brothers Hector and Alexander, and his first cousin Aeneas. In one attempt to repel the enemy ships, he was wounded in the arm by Menelaus.

In Book Six of the Iliad, Homer gives Scamander’s assessments of Hector and Aeneas as the principal leaders of the military forces defending Troy.

The advice he gave to Hector and Aeneas—“to hold the front (outside the walls of Troy), to meet the people everywhere, and to organize quickly near the gates”⁵—shows Scamander’s foresight as a warrior and as a trusted man of prophecy, whom Hector respected as such.

After the death of Alexander, in the ninth year of the war, Scamander and his brother Deiphobus clashed over who would take Helen as wife. When Deiphobus married her, Helenus left for the sacred Mount Ida, where he was captured and taken prisoner by the opposing side.

When taken prisoner in the enemy camp, Scamander used his prophetic gift to predict the fall of Troy and the dangers that would befall the enemies on their return.⁶

There are several versions of his departure from Troy and his capture by Odysseus in the ninth year of the war. One version explains it thus:

“When the Trojan Scamander was captured in battle by Odysseus, he revealed that Troy could fall only when Philoctetes and Pyrrhus joined the Mycenaeans and the others. The Thessalian Philoctetes was brought from Lemnos, where he had been abandoned after being wounded, and when healed by Machaon, he wounded Alexander with the bow and arrows of Heracles. The young Pyrrhus was also brought from Scyros to Troy, and he drove the Trojans back within their walls. Another objective of the opposing forces was to seize the Palladium, a statue of Pallas Athena that had been in the city for generations and was a gift of Zeus or Athena. Its presence in Troy ensured the city’s immunity from attack. The enemies were advised by Scamander to take the Palladium. Scamander was embittered toward the Trojans because he had not been given Helen’s hand after Alexander’s death.”⁷

Some authors note the cooperation between Odysseus and Helen in obtaining valuable information for seizing the Palladium and the city of Troy.

While absent on Mount Ida, Scamander informed his people and friends that he had not left Troy out of fear of death, but because of sacrilege—Alexander had killed Achilles in a temple—and he told them the time and circumstances under which Troy could fall. As a prophet of Zeus, he deeply respected sacred places. Three killings occurred in temples: Achilles by Alexander; King Priam by Pyrrhus in the temple of Apollo at Troy; and the killing of Pyrrhus in the temple of Delphi, organized by Orestes.

After the fall of Troy, Pyrrhus took Scamander captive along with his sister-in-law Andromache, the wife of Hector slain by Achilles. To determine a safe route home, Scamander advised Pyrrhus to return by land through Thrace and Thessaly, as sea travel might bring the danger of storms. Pyrrhus trusted him.

After reaching the kingdom of Pyrrhus’s grandfather, Scamander suggested that Pyrrhus should establish another kingdom far from his grandfather. Thus, they settled in Epirus, in the region ruled by the Molossians. We should bear in mind that Scamander’s suggestion was influenced by existing human ties—commercial, communicative, migratory—as well as by their shared origin between the Pelasgian Dardanians of Troy and those of continental Europe. After some time, Pyrrhus freed Scamander and gave him in marriage his mother Deidamia, the wife of Achilles.

Pausanias (I.II.1) mentions:

“Pyrrhus settled in Epirus in accordance with the oracles of Scamander, and with Andromache he had Molossus, Peleus, and Pergamus… and Pyrrhus gave him (Scamander) his mother, Deidamia, as wife.”⁸

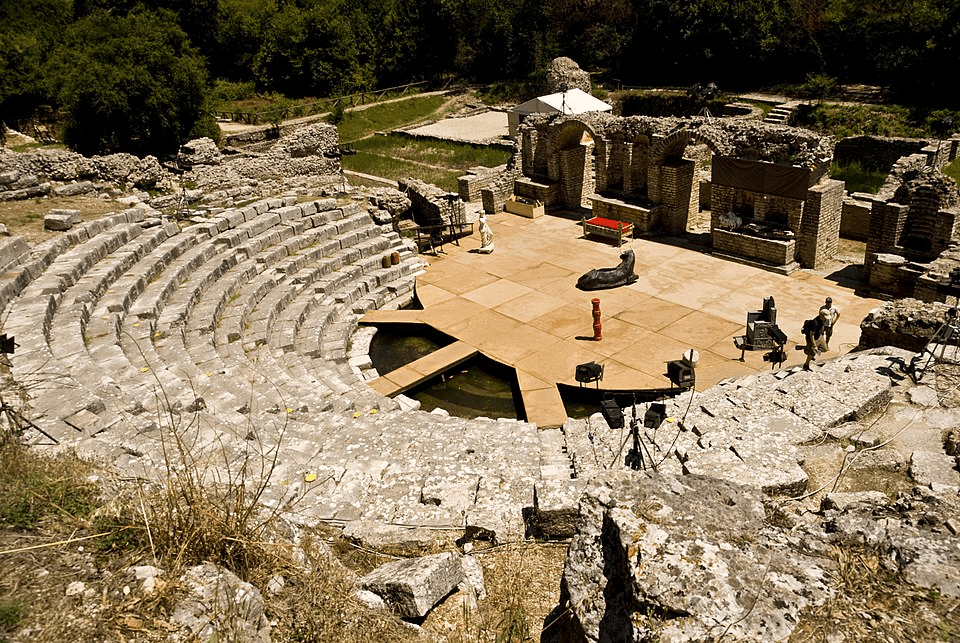

Scamander built Butrint, a fortified city in southern Albania today, in the form of a crown of trees, well protected by walls and waters.

After the death of Deidamia, the former wife of Achilles with whom he had no children, Scamander married Andromache, with whom he had three children after their return from the Trojan War and settlement in Epirus.

Scamander named the entire region he ruled Chaonia, in memory of his brother Chaon. “Chaon was a son of Priam who was accidentally killed during a hunt by Scamander. However, it is quite possible that this name derived from the ancient Pelasgian tribe of the Chaonians.”⁹

Scamander was the founder of two cities: Butrint and Chaonia (named after his brother Chaon).¹⁰ On one of the tablets found in Ioannina, addressed to the temple of Dodona, a request is described as coming from the “City of the Chaonians.”¹¹

Buthrotum was the capital of Chaonia, the second most renowned city after Dodona, which was the capital of Pelasgia and a pilgrimage site for the most famous Pelasgian heroes of the Trojan War. The name Buthrotum—today’s Butrint—derives, according to an ancient legend, from Scamander’s sacrifice of a bull to secure entry into his new settlement. The wounded bull swam into the Bay of Butrint and then walked ashore toward the hill where the castle stands today. On the eastern side of the ancient city of Butrint, on the stone arch of a gate, a carved bull can still be seen.

Buthrotum was also a second Troy on the Mediterranean coast, which amazed his cousin Aeneas on his journey to Italy. Aeneas marveled at seeing lions at the entrance as in Troy, a watchtower to detect every sudden movement of the enemy, enclosing walls difficult to breach—all reminding him of their homeland. During his stay in Albania, Aeneas called Butrint “Little Troy,” because the fortress was exactly like that of their ancestral Troy.

From Virgil’s epic poem, the Aeneid, which documents Aeneas’s visit to Albania, we learn:

“Coming along the coast of Epirus and reaching the bay of Chaonia, we landed near Butrint, a hill-top city. Scamander had asked Pyrrhus to give him Andromache, who then returned her to her own people. Aeneas felt a strong and wondrous desire, while speaking with Scamander, to learn how all this had happened. The story of Andromache is given by herself: ‘When Pyrrhus wished to marry Hermione, daughter of Leda, he handed me over to Scamander and made me the slave wife of a slave.’ Virgil also tells us of the transfer of Pyrrhus’s possessions after his death to Scamander, who cultivated the Chaonian plains and called the entire land Chaonia after Chaon of Troy, and rebuilt Troy, a well-fortified citadel at the foot of the hill.”¹²

In the Aeneid we also learn of the oracle that Scamander consulted for his first cousin Aeneas, who was to continue his journey to Italy.

Scamander advised him on the gifts to be carried down to Aeneas’s ships: gold, silver, and bronze items from Dodona, including a helmet that had once belonged to Pyrrhus.¹³

Virgil states that Aeneas landed in Italy seven years after the fall of Troy.¹⁴ This assures us that Scamander realized the dream of rebuilding Troy very quickly, based on his wisdom and that of the native Pelasgians of Chaonia.

Scamander’s acquisition of all Epirus is linked to the death of Pyrrhus, son of Achilles. After returning from the Trojan War, Pyrrhus claimed Hermione, daughter of Menelaus, who had been married to Orestes, son of Agamemnon, since Menelaus had promised her to Pyrrhus at Troy if the city were captured.

Hermione’s earlier marriage to Orestes before becoming Pyrrhus’s wife is acknowledged by Virgil (Aeneid III, 330). Homer, on the other hand, says that Menelaus promised Hermione to Pyrrhus while in Troy and celebrated the marriage after his return to Sparta. Thus Pyrrhus abducted Hermione from Orestes, and “for this reason he was killed by Orestes at Delphi.”¹⁵

After this event in the temple of Delphi, Scamander became king of Epirus. He had a son with Andromache named Cestrinus. Cestrine was the name of a city (today’s Filiati), a region, a branch of the Kalama River, and a port in Epirus.

The Chaonian colony expanded when Cestrinus, Scamander’s son, founded a city called Cestrine on the banks of the Kalama River, 12–15 miles from its mouth. The front of that part of Chaonia took the name Cestrine, and the main village—whose ruins are called Palea Venetia—appears to have been called Ilium or Troy, in memory of its founders.¹⁶

The tribe of the Chaonians controlled the entire Epirus coastline and became the shield of Epirus. According to an Argive tradition, Scamander was buried in Argos (Pausanias II.23).¹⁷

The Chaonians, as we learn from Strabo (VII.324), were once the most powerful warrior people of Epirus, until the Molossians later gained supremacy over the tribes of the land.¹⁸

With King Scamander, the concept of patriotism is embodied in the resemblance of the fortress of Butrint to that of Troy, and in the naming of settlements in Epirus and beyond the Ionian Sea, in Italy, according to the Dardanian, Pelasgian tradition.

In Scamander stand out religious faith, the preaching of Zeus, and Troy’s resistance through his heroic warfare. With his name begins a history that intertwines Pelasgian tribes, geographical names, and kings, and above all preserves the Trojan line and consolidates the foundations of Epirus as a sacred land of Pelasgia and a base of impregnable fortresses. This is shown by the Pelasgian purity of Epirus over several millennia, which even today attests to Pelasgian–Illyrian–Albanian continuity.

When Scamander was dying, the kingdom of Epirus was bestowed upon Molossus, the first son of Pyrrhus and Andromache.

Thus Epirus—this entire part of Pelasgia along the Ionian Sea—has as its ancient inhabitants the Pelasgians, not only with Dodona, but also with the early settlements of the renowned tribes of the Chaonians, Molossians, and Thesprotians, who wrote a glorious history of resistance from the arrival of the Dardanian prince Scamander to the Second World War, with Labëria and Chameria.

References

- Schliemann, Heinrich. Ilios: The City and Country of the Trojans, p. 58.

- Schliemann, Heinrich. Ilios: The City and Country of the Trojans, p. 676.

- Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, Vol. II (Eustathius ad Homer, p. 663), p. 371.

- Homer. The Iliad, trans. Richard Lattimore, line 583, p. 287.

- Homer. The Iliad, Book VI, lines 80–81, p. 100.

- Smith, William George. A Smaller Classical Mythology: With Translations from the Ancient Poets, and Questions upon the Work, p. 214.

- Young, Arthur Milton. Troy and Her Legend, p. 7.

- Apollodorus. The Library, Vol. II, pp. 250–251.

- A Commentary, Mythological, Historical, and Geographical on Pope’s Homer and Dryden’s Aeneid, p. 415.

- Arundell of Wardour Howard, Brian. Judah Scepter: A Historical and Religious Perspective, p. 29.

- Parker, Robert. The Oracles of Zeus: Dodona, Olympia, p. 261.

- Virgil. The Aeneid, trans. C. Day Lewis, pp. 68–69.

- Virgil. The Aeneid, trans. C. Day Lewis, p. 73.

- Smith, William. A New Classical Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography, Mythology and Geography, p. 20.

- Apollodorus. The Library, Vol. II,ոը p. 253.

- Leake, William Martin. Travels in Northern Greece, Vol. IV, p. 176.

- Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, Vol. II, p. 372.

- Cramer, John Anthony. A Geographical and Historical Description of Ancient Greece, p. 94.

Reference

https://www.voal-online.ch/index.php?mod=article&cat=INTERVIST%C3%8BPRESS&article=42703