Photo from WelcomeToTropoja.

By Ylli Prebibaj, 2015. Translation by Petrit Latifi, 2025.

Abstract

This article examines the Albanian–Montenegrin conflict at Qafa e Kolçit in 1915 within the broader context of World War I and the collapse of the Albanian state. It analyzes the geopolitical dynamics that enabled Montenegrin and Serbian territorial expansion, the failure of central Albanian political leadership, and the absence of national defense institutions. Particular attention is given to the local Albanian response, characterized by traditional clan-based military organization and rare intertribal cooperation among the highland communities of Nikaj, Mërtur, Shalë, and Curraj. The study highlights the strategic and symbolic importance of the Battle of Qafa e Kolçit, where coordinated resistance successfully halted a superior invading force.

The 100th Anniversary of the Albanian–Montenegrin War of Qafa e Kolçit (1915–2015)

The First World War was a very negative development for Albania, which despite the problematic developments managed to create the Albanian state, but the war crumbled the newly established structures. The balance of the short government was an inglorious end for the former Prime Minister Vlora, and after him the chosen one of Europe, Prince Vidin. With the departure of the latter, Albania lost the chance to follow a Western political course. The consequences were dramatic, the country was left without a governing authority and the image of Albania was severely damaged.

The territory of Albania during the war was transformed into a space where the interests of all its neighbors were intertwined. Serbia, Montenegro, Italy and Greece relied on it to implement the Treaty of London of 1915, according to which Italy took full control of Sazan and Vlora with the surrounding areas, Greece Southern Albania and Serbia and Montenegro would divide Northern Albania between them[1]. The northeastern regions, including the Nikaj-Mërtur region, were newly targeted by the Slavic regions.

In this situation and in the absence of any national defense institution, the region reactivated the traditional defense method of “men under rifles”, led by bajraktarë, kreënë, the heads of the djelmni, etc.

Montenegro in 1915, displayed an uncontrolled political appetite and the expansion of territories was considered a strategic priority. The army of this country was directed at the Catholic Albanian regions, while the capture of Shkodra was considered the finalization of this anti-Albanian operation.

In the historical past, there were attempts for a normal climate of Albanian-Montenegrin cross-border relations. From the second half of the 19th century until the time of the Balkan Wars, there were attempts for a joint anti-Turkish alliance. Newer researchers interpret such initiatives mainly in favor of Cetinje, without going to the end of the analysis.

In fact, they aimed at mutual interest. The Albanians’ inclinations for cooperation with the Montenegrins had an objective reason, since a significant part of Montenegro included the Vasović tribe, which tradition recognizes as of Albanian origin[2].

The Catholic missionary P. Marjan Prelaj notes that the Vasović is mentioned as a tribe of Albanian origin, which later adopted Albanian nationality and feeling[3]. The agreements in question did not work in their entirety, as a result of the change in Cetinje’s political course.

The Montenegrin army, by attacking the Gjakova Highlands and Dukagjini, two regions with valuable contributions to the anti-Turkish and later anti-Slavic resistance, aimed to secure the roads leading to Shkodra. However, the highlands recently became a serious obstacle to the military plan of the Montenegrin military strategists.

II General Developments

The political circumstances in 1915 became difficult to the point that the existence of Albania was again brought to the fore. The two states that had decisively assisted Albanian independence, Italy and Austria-Hungary, due to geopolitical changes, opposed each other. Italy and Austria-Hungary, from May 23, 1915, were involved in a war between them. Italy even positioned itself on a front with Serbia and Montenegro, against Austria-Hungary[4].

This alliance could not possibly result in a positive outcome for Albania. Disagreements arose between the Italian and Serbian governments of Pašić about the benefits in Albania.

This was one side of the coin, certainly the most negative, on the other hand is the failure of the internal political factor embodied in the figure of Esat Pasha Toptani who claimed to govern Albania. The Albanian Pasha demonstrated a pronounced lack of will to stand up for national interests. The clearest proof is the fact that in Central Albania, where at that time he was the undisputed master, no resistance was registered against the Serbian army.

Serbia took advantage of the created circumstances and without obtaining the approval of the Entente allies began military operations known as the “Albanian Expedition”, which was led by General Damian Popovic. The Serbian army within two weeks spread to most of Central Albania[5]

Tirana was occupied on June 9, meanwhile on June 28, 1915, the agreement between Ljuba Jovanovic and Esat Toptani was signed.

The second state that militarily occupied Albanian territories was Montenegro. The conquest and annexation of Shkodra and Northern Albania were the main goals of the 75-year-old Montenegrin king, Nikollë Petrovič Njegoš, the circumstances were created by the invasion of Central Albania by the Serbian army[6]

The clash with Montenegro was not new for the Albanians. The cross-border history was a history of bloody conflicts for decades, the explanation of which is related to the continuous tendency of this state to expand territorially at the expense of these regions. Shkodra in this period was the seat of the Albanian political and intellectual elite, due to the security offered by the international administration of the city.

Among the many personalities there were Hasan Prishtina and Bajram Curri, who addressed sent a letter of protest to the representatives of the great powers in Shkodër, denouncing the crossing of the Albanian-Montenegrin and Serbian-Albanian borders.

The letter underlines that “The neutrality of Albania guaranteed by your governments has now been violated and annulled. It is known that the Albanians have not maintained any supportive or aggressive stance towards the neighboring states. The moral responsibility for the murders that are continuing naturally falls on the occupiers.

Meanwhile, we announce that we are forced to fight desperately against our enemies to protect the most legitimate rights of our country”.

B. Curri and H. Prishtina request intervention in Cetinje and Belgrade, to respect the decisions of the London Conference of Ambassadors confirming the neutrality of Albania[7].

The occupation of Shkodër forced both Curri and Prishtina to leave the city. The newspaper “Populli” dated June 8, 1915, writes: “We are aware that all Kosovars who are in Shkodër today left for the Kosovo Highlands under the leadership of Bajram Beg Curri and Hasan Beg Prishtina.”[8] In the Gjakova Highlands they enjoyed great support, where they could organize resistance against Montenegro.

On June 27, 1915, units of the Montenegrin army led by General Veshovic occupied Shkodër, and from the very beginning, Albanian patriots and their families were persecuted. General Veshovic ordered the families of Hasan Prishtina and Bajram Curri to be interned in Lezha, with this action it was proven that the two patriots were the target of the Montenegrin army. However, the families in question were rescued during the sea voyage by an Austrian submarine.[9]

The Slavic conqueror of Shkodra interrupted all political and cultural activities of the Shkodra elite and other Albanians who had taken refuge there. In these circumstances, Dukagjini and the Gjakova Highlands became protagonists of a strong resistance against the new invaders.

III The Albanian-Montenegrin War of the Kolçi Pass

On the map of their objectives, the Montenegrin military strategists had marked the Gjakova Highlands, the hearth of the National Movement’s resistance. The Montenegrin army penetrated from the direction of Çerem, the Morina Pass, the Stobrda Pass and the Prushi Pass. Fighting took place in Qafë i Morinës, Spik, Zherkë, Ogjatë Ahmataj and Okol i Gashi, for three consecutive days, where the army also used artillery[10].

The military operation was launched on June 8 by units commanded by General R. Veshović, the borders were attacked in two columns in the direction of Gashi and Bytyçi[11]. In these regions there was strong resistance and many killed on both sides. The Montenegrins themselves testify to the bravery of the Albanians[12].

In these battles, 30 people were killed and 50 Montenegrins were wounded. The confrontation was in unequal conditions, for this reason the Montenegrin army broke the resistance and penetrated the highlands, where it established a military establishment at Ura Bujanit.

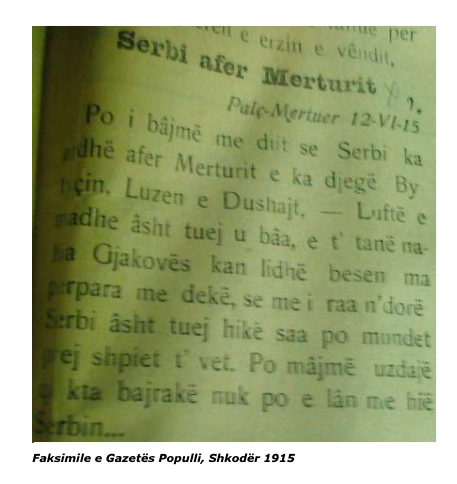

After a few days, the army in question continued its march towards Nikaj-Mërtur. On June 12, 1915, the newspaper “Populli” published the news with the title: “Serbia near Mërtur”, which read: “We are informing them that Serbia has come near Mërtur and has burned Bytyçi, Luzë and Dushaj.

A great war has been fought, and the Gjakova region has already made a pact with whoever it falls into its hands. Serbia is as far away as it can from its own land, but we are worried that these banners will not leave Serbia behind”[13].

The surprise of the Montenegrin actions was a very negative factor for the Albanian resistance, but despite the difficulties created, there were serious efforts to coordinate actions between the tribes. The inter-tribal resistance is best understood in the battle of Qafë e Kolçit, where the Nikaj, Mërtur and Shala Banners fought together.

According to Fr. Marin Sirdanit O.F. M “…The battle we fought in Qafë e Kolçit and that of Lugu i Shala are rare in our history. First, because a small number of men defeated the large Montenegrin army with great damage, and second, because the Shalans managed to capture 1500 soldiers, and in the city of Shala they all surrendered under arms”[14]

The speed of the Montenegrin operation aimed to put the Entente, which did not agree with this attack, before the accomplished fact, but also to surprise the highlanders. So, we must clarify that the attack by Montenegro was contrary to Albanian interests, but also without the approval of the allies in the war coalition.

In these circumstances, information circulated very reservedly, and this was the reason that the highlander tribes were found unprepared, since the Montenegrin army followed the strategy of rapid landing.

IV The Resistance of the Upper Curraj

The great appetite of this army did not stop at Nikaj, the maximalist border reached until then by any foreign army, but was directed to the Upper Curraj, where a special company was sent. This weightless mission alone changed the course of the entire operation of this army. Their stay in Curraj, without warning, at night and especially the use of an ultimatum language to surrender, met with opposition from the Currajs.

The latter, tried to convince the company leaders that such rules could not be imposed on their home, and asked them to leave an hour earlier. This attitude aimed to avoid facing a single company, which was not at all aware of the dead end it had ended up in. Despite negotiations sometimes through the broken Albanian of some Montenegrin soldiers and sometimes through translation, the parties could not reach an agreement.

Thus, the only alternative remained war. The clash of arms could not be avoided any longer, because it was in the interest of the Montenegrins who were waiting for the answer several hours away from the Currajs and were advancing to secure the best natural ambushes for the expected war.

Under these conditions and through a mathematics of gestures incomprehensible to the foreign military among the kren and the djelminija, the signal was given for the liquidation or isolation of the company, then the call to war was issued. In a few minutes in the Sukë i Kishës, the center of the assemblies of 100 houses, the men were gathered under the rifle.

The liquidation of the rebellious Montenegrin company that had invaded and blackmailed 100 houses of the Currajs with war was not simply a victory but its beginning. The Montenegrin army had approached Qafë e Kolçit, where the great battle was expected to take place. The kren of the Currajs, aware of the importance of this battle, but also in respect of the custom of war, issued the call to war to the neighboring bajrakëts.

Shala, which until then had borne the brunt of the war against the Montenegrins in the entire north, for which it deserves historical merit, responded with its volunteers but also with weapons confiscated from the Montenegrin army.

Meanwhile, Nikaj and Mërtur had a consolidated tradition of mutual assistance. The Currjave Paria, Balec Gjoni, Gjelosh Rama, Mark Hasani, Sylë Avdia, Kukel Ndou, Nik Musa, etc. led the long caravan of the Currajes, among whom there were even two or three from the same house.

Volunteers from the Nikaj and Mërtur also arrived at the designated battlefield, the highland warriors were led by Gjelosh Rama, Prelë Tuli, Tunxh Miftari, Mark Sadiku, Shytan Brahimi, Mark Alia, Sadri Trimi, Dedë Trimi, Ali Haka, Sylë Avdia, Zenel Selimi, Balec Gjoni, Kukel Ndou, Nik Musa, Zhujë Avdyli, etc.[15].

The dimension of this war is described as follows by Father Daniel Gjeçaj O.F.M: “The Kolçi Pass turns into Thermopylae again. Our volunteers were captured here before the Montenegrin armies climbed the hill. The priest’s blessing, Prel Tuli’s Mauser, Man Avdija’s machine gun of Palçi, Gjelosh Rama’s Karadak, Tunj Bajraktar’s and Deli Sokoli’s spear, the Nikaj flag were the signs that the war had begun…”[16].

The joint reaction proved effective, Nikaj and Mërtur, Palç and Curraj with riflemen from Shala and Shoshi were unleashed on the stunned division of Veshović, writes Gjeçaj[17]

The Franciscan parishioners were the spiritual inspiration of this existential war for the freedom and dignity of the province. Father Rrok Gurashi O.F.M., in a study published in the monthly “Hylli i Dritës”, writes: “Father Leonard Shajakaj, parish priest of Curraj, joined Curraj and left him with a spear in his back, and on the other side, Palç’s men and P. Bernard Llupi dueled with one side and pushed the Montenegrins to Qafë i Kolçit.

There, the Montenegrins tried to retreat, but P. Bernardin Llupi had taken with him a machine gun, which Hysni Curri had left behind… when he returned from Durrës in 1914, the Montenegrins heard the machine gun, they were afraid that it was Austria, they went to them, shouting as if they had been taken, they threw their weapons to the ground and fled…”[18]

The great role of the aforementioned Franciscans is also evidenced by the documentation preserved in the Central State Archive. A documentary source highlights the major role played in the battle of Kolçi by Fr. Bernard Llupi and Fr. Ciril Cani[19].

An interesting treatment is found in the historian Father Marin Sirdani O.F.M., according to him: “…The Montenegrin army was already on the move and the Albanian troops were on their backs, the national flag was still not looked upon with favor. The patriotic Bajram Curri, with his own troops, fought with the Catholic troops of the Nikaj and the Mërtur in Qafë i Kolçit.

These troops were led by the local army, the Franciscan P. Bernardin Llupi with the Albanian flag. When the two troops joined, Bajram Begu called the friar and asked him to put the Albanian flag on the backs of the Montenegrins so that the Albanian flag would not be infringed. Bajram said to them: “Let us free the country from foreigners and then build Albania as we want it, because let them know that we love our State and the Albanian flag.” “…they don’t kill us with rifles, they suffocate us with stones”. The friar, seeing his advice as unreasonable, waved the flag and threw it in the air, continuing to mseymen…”[20].

In the literature of the early 20th century, the great role that the Curraj and Epër played in this bloody war is evidenced. As protagonists of the battle in question, they are given an extraordinary dimension, thus Gjelosh Rama is described as a “Dragon” boy , the bravery of Captain Ali Haka is also appreciated, etc. Meanwhile, the resistance is given a historical dimension, when among other things it is written, “The brave are Nikaj and Shalë”[21].

The conflict of July 1915 dealt a strong blow to the Montenegrin army, in the Kolçi Pass, out of 150 Montenegrins, only about 40 of them survived. The Montenegrins were pushed to the Valbona bridge, and even the Montenegrin reinforcements that came from Shkodra were unsuccessful[22]

There were also losses in people on the Albanian side. According to the data, in the Kolçi Pass war, Ali Hak Niklekaj, Kel Sejdi Prebibaj, Nik Deli Progni, Sadri Trim Pjeternikaj, Zhuj Avdyl Uknikaj, etc.[23] were killed.

Recently, we have also consulted some documents that have not been used so far about this event. In one of these acts it is stated: “…In the war we fought in Qafë i Kolsh with Montenegro, the deku was killed fighting with heart and soul, you called him Kol Seda, because he loved his homeland more than life…”[24]

According to Dodë Progni, in the organized resistance Nikë Delia (Progni) from Salca, Sadri Trimi, the first of the Mërtur youth from Shëngjergji, Ali Haka (Kapit) and Sejdi Miftari from Gjonpepaj, Gec Prendi from Curraj Poshtëm, Zhuj Avdyli from Lekbibaj, etc.[25] It should be noted that not all of the above-mentioned were honored as they should have been in the communist decades.

The biography of their descendants probably had an influence, but another objective reason was the lack of sources for the investigation of the event.

Before the 1990s, with the exception of materials collected in the Archives of the Historical Museum of Tropoja, this event was somewhat neglected on a national scale. Thus, in many regions of Albania, one can find memorials, statues or plaques for events that are significantly less important than this one.

The commemoration of this event had fallen prey to the ideological tendencies of the time, such is also an article of the propaganda newspaper of the time “Bashkim”, according to which “the battles of 1915 marked new pages of heroism in the war against the invaders… the resistance continued in the Kolçi Pass… the war in completely inverse proportion to the forces and combat techniques, where the enemy was many times superior, turned in favor of the highlanders… even today their (Montenegrins) graves are found in that Pass[26]. This was more or less the collective mindset at that time, for the commemoration of events of this historical dimension.

The Battle of the Kolçi Pass in 1915, reconfirmed the tradition of the Gjakova Highlands to be masters of the defense of the province. The contribution given by the Curraj nobility, Nikaj, Mërtur, Shala and all the men under the rifles of these bajraqs was a good omen for the general resistance that followed this event.

The Currajs, by rejecting the offer of Montenegro and starting the war, first of all defended the house of God, where the parishioners served with numerous sacrifices and undoubtedly their own clandestinely and treacherously attacked.

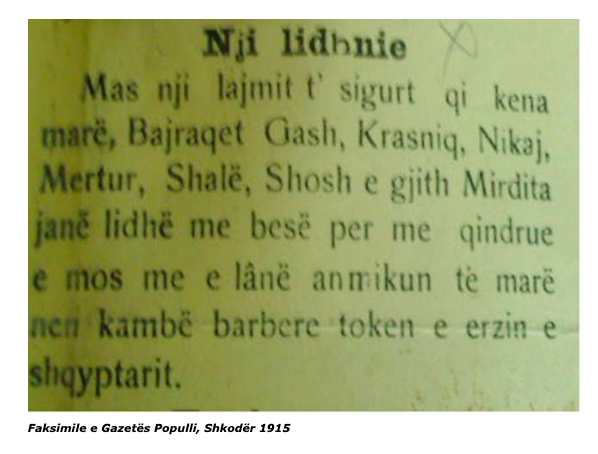

The joint reaction on the front of the Kolçi Pass was a prudent action of the heads of the Nikajs, Mërtur and Shala, but also of Geghysen (Krasniqe), who encountered the Montenegrin troops, after the latter barbarically attacked them during their retreat. Thus, this war was not isolated, but a serious attempt to remove the invader from the entire region and why not to contribute beyond the Nikaj area. The dimension of this resistance has been considered by the press and chroniclers of that time time as a nationwide inspiration.

Bibliography

Archival Sources:

*Central State Archives: P. 133; P. 178.

*Central State Archives Library.

Press and Periodicals:

Bashkimi, No. 242, Tirana 1978

Calendar of the Year 1925, No. 34, Printing House of the Immaculate Conception, Shkodër 1925

Hylli i Dritës, No. 1, Shkodër 1934

Hylli i Dritës, No. 12, Shkodër 1937

Populli – No. 74, Shkodër 1915

Populli – No. 79; Shkodër 1915

Populli – No. 89, Shkodër 1915

Historiographic Publications:

Father Marin Sirdani, “Enlightenment of Albanian History, Culture and Art”, Shpresa, Prishtina 2002

Ajet Haxhiu, “Hasan Prishtina and the Patriotic Movement of Kosovo”, Naim Frashëri, Tirana 1968

Ali Lushaj, “The Shipshani of the Gjakova Highlands”, Dardania, Tirana 1999

Charles and Barbara Jelavich, “The Establishment of the National States of the Balkans”, 1804-1920, Dituria, 2004

Dodë Progni, Zef Doda, “Nikaj-Mërturi”, Shtjefni, Shkodër 2003

Elez Qerimaj “The Gjakova Highlands (Tropoja) in the Course of National History”, Kristalina-KH, Tirana: 2008

Muin Çami, “Albania in International Relations (1914-1918)”, Academy of Sciences of the Albanian Socialist Republic, Tirana 1987

Niman Ferizi, “The Curri Family”, Albania, Constanta 1935

Pal Dukagjini, “Prelë Tuli i Salcës”, Center of Albanian Catholics Abroad, Rome 1988

Visaret e Kombit, Vol. X, “Lahuta e Kosova”, collected by teacher Myrteza Roka, Typographic Building “Gurakuqi”, Tirana 1944

*This presentation was held on July 18, 2015, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Kolçi.

Footnotes

- Charles and Barbara Jelavich, The Formation of the Balkan National States, 1804–1920, Dituria, 2004, p. 292.

- Kalendari i Vjetës 1925, No. 34, Shtypshkronja e së Papërlyemes, Shkodër 1925, p. 42.

- AQSH F. 133 V. 1958. D. 1306, pp. 1–3.

- Muin Çami, Shqipëria në Marrëdhëniet Ndërkombëtare (1914–1918), Akademia e Shkencave e RPS së Shqipërisë, Tiranë 1987, p. 177.

- Ibid., p. 180.

- Ibid., p. 189.

- Ajet Haxhiu, Hasan Prishtina and the Patriotic Movement of Kosovo, N. Frashëri, Tiranë 1968, p. 120.

- Populli No. 74, “Lajme t’Mbrendshme,” Shkodër 1915, p. 3.

- Niman Ferizi, Familja Curri, Albania, Konstancë 1935, p. 24.

- Dodë Progni, Zef Doda, Nikaj-Mërturi, Shtjefni, Shkodër 2003, pp. 161–162.

- Populli, June 11, 1915, p. 2.

- Populli, No. 89, Shkodër 1915, p. 2.

- Populli, No. 79, “Serbs near Mërtur,” Shkodër 1915.

- Hylli i Dritës, No. 1, Contribution of the Albanian Catholic element to the homeland, Shkodër 1934, p. 39.

- Dodë Progni, Zef Doda, op. cit., pp. 162–163; “Historik Fshatrash,” Tropojë Historical Museum, L.5, D.3, p. 31.

- Pal Dukagjini, Prel Tuli i Salcës, Albanian Catholic Center Abroad, Rome 1988, p. 76.

- Ibid., p. 84.

- Hylli i Dritës, No. 12, Dukagjini for the freedom of the homeland, Franciscan Press, Shkodër 1937, pp. 573–574.

- AQSH F. 133 V. 1942 D. 1233, p. 81.

- Father Marin Sirdani, Illuminations of Albanian History, Culture, and Art, Shpresa, Prishtina 2002, p. 180.

- Visaret e Kombit, Vol. X, “Lahuta e Kosovës,” compiled by teacher Myrteza Roka, Ngrehina Typografike “Gurakuqi”, Tirana 1944, pp. 59–60.

- Muin Çami, op. cit., p. 200.

- Ali Lushaj, Shipshani i Malësisë së Gjakovës, Dardania, Tiranë 1999, p. 164; Elez Qerimaj, Malësia e Gjakovës (Tropoja) në rrjedhën e historisë kombëtare, Kristalina, Tiranë 2008, p. 193.

- AQSH F. 178 V. 1940 D. X-333, p. 28.

- Dodë Progni, Zef Doda, op. cit., pp. 163–164; AMHT, Nominal list of martyrs and decorations, L.2, D.1.

- Bashkimi, No. 242, Curraj Epër in the Preher of the Alps, Tirana 1978, p. 2.