From the Archaeological Institute of America. Material collected by Artur Vrekaj. Translation and editing by Petrit Latifi.

Abstract

This article revisits the ancient tradition that the Trojan elder Antenor migrated westward after the fall of Troy and founded settlements in the northern Adriatic region. Drawing primarily on classical sources such as Livy and Homer, it argues that Antenor has been unfairly overshadowed by Aeneas and miscast as a traitor in later legend. The text examines early literary accounts, archaeological context, and the potential routes taken from Troy to the Adriatic. It suggests there is historical plausibility in linking Trojan survivors with the origins of the Veneti and other peoples in northeastern Italy, contributing to a reevaluation of Mediterranean migrations after the Bronze Age collapse.

The Tradition of Antenor and its historical possibility

“Iam primum omnium satis constat Troia capta in ceteros saevitum esse Troianos: duobus, Aeneae Antenorique, et vetusti iure hospitii et quia pacis reddendaeque Helenae semper auctores fuerunt, omne ius belli Achivos abstinuisse: casibus deinde variis Antenorem cum multitudine Enetum, qui seditione ex Paphlagonia pulsi et sedes et ducem rege Pylamene ad Troiam amisso quaerebant, venisse in intimum maris Hadriatici sinum, Euganeisque, qui inter mare Alpesque incolebant, pulsis, Enetos Trojanosque eas tenuisse terras. Et in quem primum egressi sunt locum Troia vocatur, pagoque inde Troiano nomen est: gens universa Veneti appellati.” — Liv. I, 1.

Translation of quote

“Now, first of all, it is sufficiently established that after the capture of Troy the Trojans were savage towards the rest: two, Aeneas and Antenor, and because of the ancient right of hospitality and because they were always the authors of the peace and the return of Helen, the Achaeans abstained from all right of war: then in various cases Antenor with a multitude of the Enetae, who were driven out of Paphlagonia by sedition and were seeking their seat and leader after the loss of king Pylamenes at Troy, came to the innermost bay of the Adriatic Sea, and having driven out the Euganeans, who lived between the sea and the Alps, the Enetae and the Trojans held those lands. And the place to which they first went out is called Troy, and the village from there is called Trojan: the whole nation is called the Veneti.” — Liv. I, 1.”

Among the minor cruelties of fate there is, perhaps, none more unkind than to be assigned the rôle of companion to a celebrity and to fill the part of amicable shadow to a better advertised or possibly more brilliant associate. Fidūs Achates, Patroclus, Pylades, to a great extent submerge their own individuality in that of their companions.

A somewhat similar lot has befallen Antenor, who set out with Aeneas after the Trojan War and whose adventures are summed up by Livy in the brief phrase “various vicissitudes,” while the tale of Aeneas has filled more pages than one would venture to guess.

The predominant importance of Aeneas in the history of Italy has overshadowed his colleague who, however, deserves to be rescued from comparative oblivion and to be cleared of the accusation which transformed the discreet old hero of the Iliad, the respectable and surely congenial companion of the pious Aeneas, into a traitor and launched him with tarnished reputation on his further adventures.

Aeneas, too, was smirched by the same scandal; evidently it was inconceivable that anyone could have escaped from Troy without treachery, and the friendliness of Antenor towards Menelaus and Odysseus as ambassadors of the Greeks, his chivalrous appreciation of the qualities of his enemy Odysseus, his gentle manner towards Helen, his advice to restore her to the Greeks, were interpreted by later writers to mean that Antenor could not have been loyal to the Trojan cause.

Indeed, the story that a leopard’s skin was hung upon the door of Antenor in order that the Greeks might spare his house had become so much the current version that it was represented by Polygnotus in his “Destruction of Troy” at Delphi.

But there is not a suggestion of this in Homer’s charming picture of the sage seated upon the tower at the Scaean gate among the elders who “had now ceased from battle for old age, yet were they right good orators, like grasshoppers that in a forest sit upon a tree and utter their lily-like voice.”¹

A kind of rejuvenation is implied by Livy, for the leader of a wholesale migration of a people in search of new homes in a distant land can hardly have been a very old person far beyond the fighting age. In other respects Livy’s Antenor is much like Homer’s and escaped the severity of the Greeks because of the ancient tie of hospitality and the advice to restore Helen and bring about peace, in both of which he is closely associated with Aeneas.²

This, too, is in accord with Homer, who tells how two of Antenor’s sons, “Archelochus and Acamas, well skilled in all the ways of war,” accompanied Aeneas, leader of the Dardanians.³ Thus there was a close connection between Aeneas and Antenor from the earliest times of which we have any record, and Livy is not whitewashing the founder of his native Patavium when he presents him as an eminently respectable character.

But although Antenor himself was too old to take part in the fighting, he was well represented by his sons, several of whom distinguished themselves and fell in their country’s cause. Homer mentions eleven, and in a few words individualizes each: Helicaon, who had married Laodice, the fairest of Priam’s daughters;⁴ the inseparable Archelochus and Acamas, the former of whom “no coward, nor born of cowards, but brother of horse-taming Antenor, or a child, for he most clearly favoured his house,” was slain by Ajax and was avenged by his brother, young Acamas, like unto the immortals, who “boasting terribly,” slew Promachus,⁵ and after having escaped from Penelaus fell a prey to the spear of Meriones.⁶

Ajax claimed another victim in Laodamas, leader of the foot-men,⁷ while Demoleon, “brave stemmer of battle,” fell pierced in the temples through his bronze-cheeked helmet by the spear of Achilles.⁸

Noble Agenor, a princely man and strong, fared better against Achilles, for he fought him like a leopardess going forth from a deep thicket, standing his ground till he put Achilles to the proof, and when his spear which struck the greave of Achilles with a terrible noise bounded back and Achilles rushed at him, Apollo shrouded him in a mist and took his place.⁹

By his courageous resistance of Achilles, Troy was for the time being saved from capture by the Achaeans; Agenor had earlier gathered with the chiefs, Hector and Aeneas, and his two brothers, Polybus and Acamas, ready to meet the onslaught of the Greeks.¹⁰

Of Polybus we know nothing further, while another son, Laodocus, a stalwart warrior, is mentioned only as the form under which Athene appeared to Pandarus. Still another son, Coon the eldest, had wounded Agamemnon, but sacrificed his own life in trying to rescue his brother Iphidamas, who in certain respects is the most interesting of the sons of Antenor.

No less striking is the picture of Antenor’s wife, Theano, the fair-cheeked priestess of Athene, going to the temple with the robe which she laid on the knees of the beauteous-haired Pallas with the prayer that Diomedes might be laid low, and with the promise of rich sacrifice “if thou wilt have mercy on the city and the Trojans’ wives and little children.”

Kind and tender-hearted, she brought up Pedaeus, Antenor’s bastard son, carefully like to her own children, and was beautiful as well as good. She was the daughter of Cisseus, king in Thrace, and it was to his grandfather that Iphidamas had been sent when a child to be reared in the king’s hall in that land rich in soil, the mother of sheep. Not even the king’s daughter for bride could keep him there, for he started at the first news of the coming of the Achaeans, with twelve ships that followed after him.

These he left in Percote, but went himself by land to Ilios, and there he was the first to encounter Agamemnon, who furiously, like a lion, smote his neck with the sword and unstrung his limbs.

It seems almost incredible that in the face of actions like these on the part of Antenor’s sons, Antenor himself could ever have been perverted into a traitor capable of betraying the city for whose sake he had lost so much, but in the course of time accretions and inconsistencies had been added to the story.

In the painting in the Lesche at Delphi, Theano appears with her children, Glaucus and Eurymachus, otherwise unknown, while to Antenor is given a daughter, Crino, who carries a baby in her arms. Pausanias depicts the members of the family group as sorrowful, while servants load a coffer and other goods on the back of an ass. This was at any rate a more comfortable way of moving than that adopted by Aeneas, and it suggests a dignified and decent exit even if not a cheerful one.

Homer makes no connection between Antenor and the Eneti of Paphlagonia, who were still under the leadership of Pylaemenes in the Iliad, but Livy is closer to Strabo’s version which states that the Eneti, when they lost their leader, crossed to Thrace and reached Venetia, and that according to some, Antenor and his sons took part in the migration and settled at the head of the Adriatic.

The most generally accepted modern view is that these two far-separated areas are associated merely because of the chance resemblance of the names, and Dr. Leaf thinks that there was no tribe of Eneti, but that Enetoi is local rather than tribal and may be derived from a town called Enetoi or Enetol.

If for the present we lay aside the question of who were the Veneti of Italy and what connection they may have had with others of a similar name, we may get some light on the subject by tracing the later history of Antenor and, if possible, the route which he took to Italy. Livy does not help us here.

All we learn from him is that Antenor and Aeneas followed different paths after the sack of the city; that is, in the hazy period of the Dark Ages when the transition from the Bronze to the Iron Age was taking place, at a time when the VI city, or Mycenaean Troy, was a smoking ruin and the VII city of the Early Iron Age had scarcely come into being.

Is it possible to reconstruct the route which Antenor may have taken? The literary evidence suggests little beyond the story that he arrived in Italy, near the head of the Adriatic, and does not determine whether he came by land or by sea. According to one version the sons of Antenor went to Cyrene, but this is not said of Antenor himself.

Servius tells us that Antenor came with his wife, Theano, and his sons, Helicaon and Polydamas, and other companions, to Illyria, and having been involved in war by the Euganei and King Veleso, he was victorious and founded the city of Padua. Livy says that when the Heneti and Trojans reached Italy they expelled the Euganei, who dwelt between the sea and the Alps, and took possession of the country.

Antenor and his followers, then, were not pioneers settling in wild country among barbarous tribes and bringing civilization for the first time to that district, but like Aeneas in Latium they found other peoples established and contended with them for possession of the land. Unlike Aeneas and his Trojans who according to tradition fused with the earlier inhabitants and formed the Latins, the companions of Antenor are said to have driven out the Euganei and taken over their territory.

History is full of instances where one tribe or race is stated to have been expelled or even exterminated by the newcomers, but the complete wiping out or displacement of a people is a thing which seldom happens in fact.

Massacres and butcheries are fortunately the exception rather than the rule, and in this case the Euganei were merely expelled, and there is no reason to believe that they all went away leaving none to live under the new masters. Probably some of the Euganei remained behind when the majority were pushed northwards and westwards towards Lake Garda, Iseo and the country north of Brescia, where the names of the Trumpilini and Camunni survived in the valleys.¹

Excavations testify to a varied population in northeastern Italy, interpreted by some as the Euganei and their conquerors, the Veneti. Livy’s narrative indicates that Veneti and Trojans shared in this conquest, since the whole people was known by the former name, while the place of landing was called Troy, as was the tradition about Aeneas, and the canton was called Trojan.

Is Livy merely proceeding along conventional lines and making the hero of his own district a sort of double of Aeneas, or can we really find any trace of Trojan connections in the northern part of Italy? Can we link the civilization of Troy with that which extends around the head of the Adriatic and branches into the two peninsulas, the Italian and the Balkan, on both sides of the sea?

I believe that we can, and that a careful study of the places where remains of a similar character occur will suggest the route Antenor may have taken, and will show that Livy’s account reflects a true happening which passed into the tradition he relates.

A puzzling question is why Livy does not connect Antenor with his own Padua, as has been done by others,² since it offered him an excellent chance to claim as long and distinguished an ancestry for his city as for Rome itself.

There is no suggestion in Livy that Antenor was a family skeleton in spite of Servius’s comment that Livy regards him as a Trojan traitor; Servius has absolutely no ground for laying the responsibility at Livy’s door, wherever the story may have arisen. But when to this day the tomb of Antenor is exhibited as one of the sights of Padua,³ Livy’s reticence on the point is extraordinary.

The connection of Antenor with Padua was observed into imperial times. Games which were celebrated every thirty years in his honor⁴ are said by Tacitus to have been instituted by Antenor himself, the fugitive from Troy.

The traditional text calls them ludis celastis and everyone agrees that celastis is corrupt. Of the attempted emendations⁵ the only possible one seems to me caestatis, “games of the cestus.”

This type of boxing match was exceedingly popular among the Greek and Trojan heroes, and the descriptions by Homer, Apollonius Rhodius, Theocritus and Vergil⁶ are admirably illustrated by the scenes on the bronze repoussé cistae and situlae from this vicinity which show the contestants equipped for the struggle while the prize, generally a helmet, is placed in the foreground.

One reason for the death of Thrasea Paetus at the hands of Nero was that he had assisted at these games in his native Padua but absented himself from the Juvenalia at Rome. Tacitus’s statement that Thrasea had also performed in the habit of a tragedian suggests that jealousy of Paetus may have had as much influence with Nero as mere indignation at Paetus’s supposed indifference.

The literary evidence may be summed up as follows: Homer’s Antenor is a wise old man with friendly connections with the Greeks, associated in cordial relations with Aeneas, and the father of many sons who fell for Troy. His wife was a Thracian and one of his sons was brought up at the court of his maternal grandfather.

Livy tells no details of Antenor’s early history except to couple him with Aeneas as the recipient of good treatment from the Greeks which enabled them to escape from Troy. He adds that Antenor passed through various vicissitudes, reached the head of the Adriatic with the Heneti of Paphlagonia, whose leader he had become, expelled the Euganei, took the country, and that the place where they first landed was called Troy, the canton named Trojan, but the nation in general called Veneti.

Vergil’s Antenor comes up the Illyrian coast past the Liburnians to the gulf’s head and beyond the springs of Timavus. He builds Patavium for the Trojans, thus giving them a place and name.

Servius adds Antenor’s wife and two sons to the party, and calls the king of the Euganei Veleso. He says it was not Illyria nor Liburnia, but Venetia, which Antenor held, while Strabo tells us that Antenor and his four sons, with the surviving Heneti, are said to have escaped into Thrace, and thence into Henetica on the Adriatic.

Antenor’s connection with Italy is post-Homeric; he reaches there from the head of the Adriatic either by land or sea along the coast of Illyria. Presumably there were two routes he might have taken from Thrace, either via the Danube valley or across the mountains to the Illyrian coast. Before considering the geographical possibilities, it may be as well to take a brief glance at the remains in northeastern Italy in order that we may recognize them if they occur along the route.

The district in northeastern Italy known as Venetia is scarcely capable of exact definition, since its boundaries varied at different times.

Even in the days of recorded history it belonged successively to the Veneti, the Cisalpine Gauls and the X Region of Augustus, while tradition has already indicated a very mixed population for an earlier date.

Border towns are spoken of as belonging now to the Veneti, now to the Gauls, Rhaetians or Euganei, and the river boundaries are variously stated as extending from somewhere about the Adige on the west to the Formio or the Timavus on the east.¹

In prehistoric times the frontiers were doubtless as uncertain as our information, and it is futile to try to circumscribe too exactly the habitat of a people who were constantly at war with their neighbors. With the coming of the Gauls the Veneti remained like an island in a sea of Gallic tribes and were included in Cisalpine Gaul. Roman colonies of the third and second centuries B.C. doubtless added another element to the population.

Under Augustus Regio X included Venetia and Istria. The association of Venetia with the territory to the east around the head of the Adriatic rather than with the western territory held by the Gallic tribes appears to rest on a sound racial as well as geographical basis, for the Veneti were incessantly fighting with their neighbors the Gauls, and although in the course of time they became almost indistinguishable from them in respect to customs and dress, they preserved their own language.²

They sometimes took the side of the Romans against the Gallic tribes of the Cisalpine area and appear to have been rather more advanced than some of their neighbors, for Livy speaks of the importance of Patavium in 302 and contrasts the Veneti with their contemporaries the Illyrians, Liburnians and Istrians, *“gentes ferae et magna ex parte latrociniis maritimis infames.”*³

It is almost hopeless to attempt to solve the problem of the race of the very ancient Veneti on the basis of the similarity of their name with those of peoples elsewhere. A strange combination of Greeks and Trojans might easily be postulated for central New York State with its Troy and Ilion, its Ithaca and Syracuse, if we were otherwise ignorant of its history.

Of the Paphlagonian Eneti we have already spoken, and other people named Veneti lived near the Baltic region. Still better known are the Gaulish Veneti in Armorica against whom Caesar fought. Peoples named Veneti may in the Early Iron Age have spread northward from the Hallstatt area along the amber route to the Baltic, westward across Gaul, and southward into Italy, since there is a certain resemblance among these culture areas, but any element common to them all must have become considerably modified by the tribes with whom they came into contact.

The ancients had their own views as to the origin of the Veneti. Strabo believed them to be Gauls akin to those whom Caesar had met on the borders of the ocean, and who invaded Italy, but he expresses his personal opinion with a certain reserve;¹ while Polybius says their civilization is much the same, but their language entirely different. Herodotus calls them an Illyrian tribe, and connects them with the Illyrians on the other side of the Adriatic.²

The resemblance between the Venetic and Illyrian languages³ would be another point in favor of associating the Veneti with the Illyrians rather than with the Gauls.

The supposed relationship between the Adriatic Veneti and Homer’s Paphlagonian Eneti might be explained by the hypothesis that both were Thracians or Illyrians whom migrations had scattered to Asia Minor and to Italy. The commonly accepted view of migrations of Phrygians and other tribes to Asia Minor where they formed a considerable element in the Troad and elsewhere makes a Thracian migration to Paphlagonia entirely within the bounds of possibility.

Pliny says the Veneti were of Trojan race and quotes Cato as his authority for the statement.⁴ Certainly the Trojans were of very mixed stock and a good share of European blood went to their making.

On the basis of the literary statements alone there is plenty of evidence regarding their customs and career to differentiate the Veneti from their neighbors.⁵ The archaeological remains as well as certain ethnological survivals to this day⁶ point to the same conclusion.

The persistence of their own language is supplemented by a certain permanence of racial characteristics that survived the successive invasions which the territory of the Veneti experienced. Livy points out that they were immune from Etruscan rule which was so widespread “excepto Venetorum angulo,”¹ but their isolation from influences moving in a northerly direction did not save them from invasions and influences which came from the opposite quarter.²

Yet in spite of this, the people of Venetia have always exhibited local characteristics, as the Venetian school of painting shows. The love of color, of the picturesque and the dramatic which we associate with the Venetians of the Renaissance were already foreshadowed in the pages of Livy.³

The remains in Venetia and Gaul in the Early Iron Age are by no means identical, but affinities with Illyria are more clearly marked, since both are offshoots from the Hallstatt civilization which forked southwards on either side of the Adriatic. The remains of the Early Iron Age in Italy fall into distinct groups separated from each other partly through geographical reasons, and partly because of the different history of the areas.⁴

The contrast between northern and southern Italy evident as early as the neolithic period continues through the Bronze and Iron Ages. In a word: the connections of the south are with the Mediterranean, of the north with the Alpine districts. Central Italy—Latium and especially Etruria—underwent a different development, the result largely of foreign influence which reached them through commerce and the importation of various objects.

Outstanding local differences demarcate the northwestern or Golasecca tombs⁵ from the civilization of Bologna⁶ or that of Este.⁷ It is this last area, Atestine or Venetian, which particularly concerns us. The three periods which correspond respectively to the Benacci I, II and Arnoaldi tombs of Bologna extend from the pozzo or buca to the fossa graves and fit into the general framework of the Hallstatt and early La Tène periods of trans-Alpine Europe.

By some scholars the three periods have been assigned to the Euganean, the Venetian and the Gallic inhabitants of the area. In any case they indicate a mixed population, which is just what the traditions have led us to expect. It would take us too far afield into the details of prehistoric archaeology to describe fully the finds from the tombs.

There seems no violent break between periods I and II, and for that reason both are attributed to the Veneti rather than to their predecessors, the Euganei, but it is certainly true that period II exhibits characteristic traits and at the same time shows a remarkable advance in the arts, one contributing cause being the progress made in metal work which is richly represented, and which was freely imitated in terra-cotta.¹

The frequent occurrence of imported articles made of amber and glass, the introduction of new techniques and motives, all point to an increased commercial activity and indicate connections which we may hope to trace presently. Many objects belonging to period III are distinctly Celtic in character and indicate a foreign—or new—element, but the inscriptions continue to be written in the Venetian language.

The multifarious objects so copiously illustrated in the works of Montelius² and in the Notizie degli Scavi find their closest counterparts around the head of the Adriatic and along its opposite side, where similar weapons, jewelry, pottery, and particularly the characteristic situlae are plentifully represented, both by the early Hallstatt form of cista à cordon with its vertical sides, and by the later situla of curved outline with its zones of repoussé decoration.

To the earlier period belong also the buckets ornamented with designs in dotted or punched technique, and the patterns and motives of the early geometric style of central Europe, while the second period exhibits strong influences of an oriental character in the winged animals, heraldic groups, and motives which repeat those of the pre-Attic pottery.³

This Graeco-oriental influence is obviously an importation, although it is impossible to tell whether it reached the upper Adriatic via the Danube⁴ or through the Adriatic along the old amber route which led to Greece.⁵ The cistae evidently became a firmly established industry in Este and in Bologna, though the two styles may be distinguished by the fact that the Bolognese cistae have fixed handles while those of Este are movable.⁶

The Este type predominates in central Europe, and although Grenier believes that it was derived from the Bologna type which, in turn, he thinks came from Etruria,⁷ few agree with this explanation of a style so particularly characteristic of the Venetian district and its vicinity and one which forms a fairly homogeneous group.

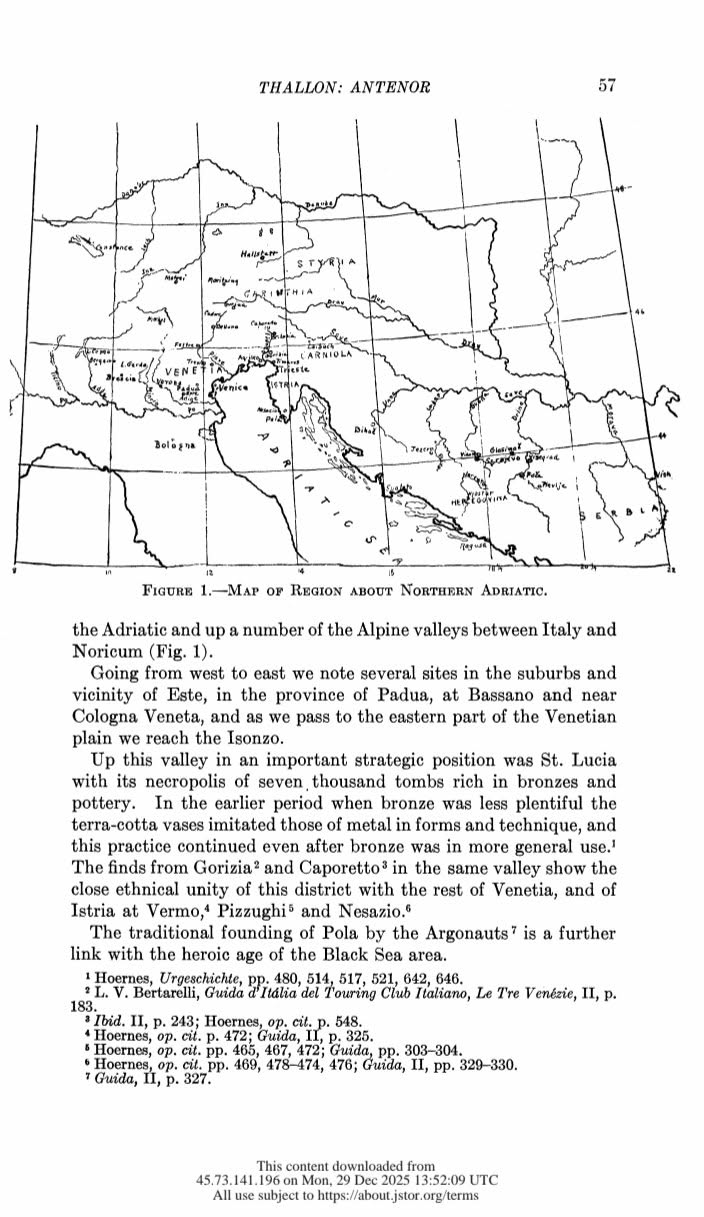

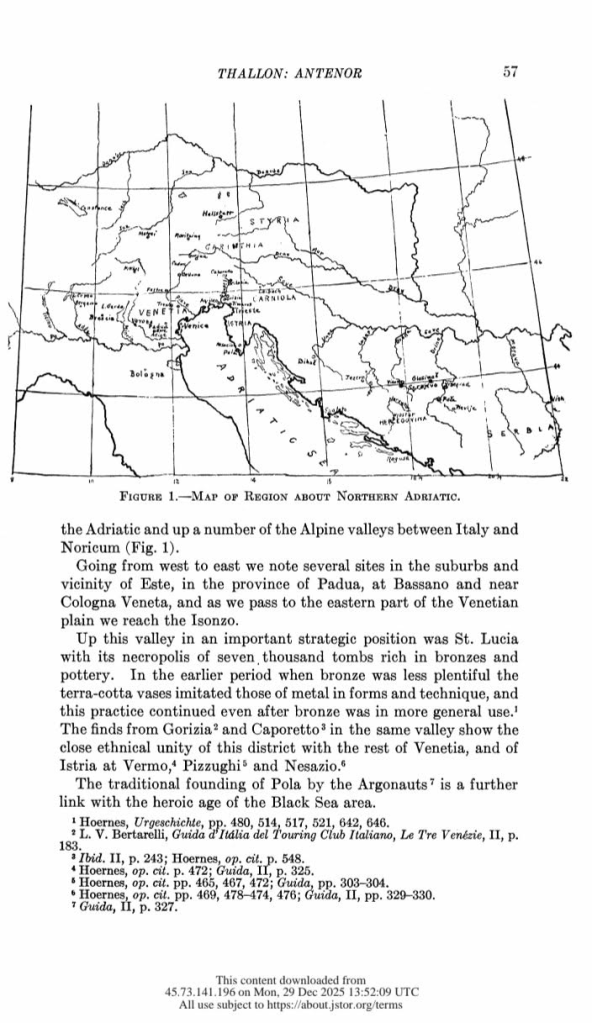

The remains of this Venetian industry radiate out from Este as a centre, extending over the level plain, along the coast at the head of the Adriatic and up a number of the Alpine valleys between Italy and Noricum (Fig. 1).

Going from west to east we note several sites in the suburbs and vicinity of Este, in the province of Padua, at Bassano and near Cologna Veneta, and as we pass to the eastern part of the Venetian plain we reach the Isonzo.

Up this valley in an important strategic position was St. Lucia with its necropolis of seven thousand tombs rich in bronzes and pottery. In the earlier period when bronze was less plentiful the terra-cotta vases imitated those of metal in forms and technique, and this practice continued even after bronze was in more general use.¹ The finds from Gorizia² and Caporetto³ in the same valley show the close ethnical unity of this district with the rest of Venetia, and of Istria at Vermo,⁴ Pizzughi⁵ and Nesazio.⁶

The traditional founding of Pola by the Argonauts⁷ is a further link with the heroic age of the Black Sea area.

Footnotes:

¹ Hoernes, Urgeschichte, pp. 480, 514, 517, 521, 642, 646.

² L. V. Bertarelli, Guida d’Italia del Touring Club Italiano, Le Tre Venezie, II, p. 183.

³ Ibid., II, p. 243; Hoernes, op. cit., p. 548.

⁴ Hoernes, op. cit., p. 472; Guida, II, p. 325.

⁵ Hoernes, op. cit., pp. 465, 467, 472; Guida, pp. 303–304.

⁶ Hoernes, op. cit., pp. 469, 478–474, 476; Guida, II, pp. 329–330.

⁷ Guida, II, p. 327.

We must now turn to the mountain passes from Venetia to the trans-Alpine districts.

One route led from Treviso via Feltre up the Piave to Belluno, where there was a palaeo-Venetic necropolis,¹ and thence through the Cadore valley, where situlae were found with inscriptions in the Venetic language on them.² Although these inscriptions belong between 500 B.C. and the Christian era, there is no reason why this well-established track between the Adriatic and central Europe may not have been utilized at an earlier date.

That the Venetic language had spread to the Tyrol as early as the fifth century is indicated by the inscribed objects from a little place called Gurina in the upper Gail valley between that river and the Drav.³

Farther to the west at Matrei near the Brenner Pass,⁴ near Moritzing in the Iese valley,⁵ and at Mechel in the Valle di Non,⁶ similar finds indicate close connections with the Veneti.

The Gail and Drav valleys lead eastward to Styria, where at Kuffarn and Klein Glein the likeness to the Venetian objects is less close.⁷ In Carniola in and around Laibach, particularly at Watsch and St. Marien, the resemblances are more marked, although Carniola does not reach the coast.⁸

To turn next to the Illyrian side of the Adriatic. The most notable centres here are the famous sites of Glasinac and Jezerine in Bosnia, differentiated respectively by Professor Ridgeway as Celtic and Illyrian, although there hardly seems adequate reason for so doing, since Jezerine is of slightly later date and continues into the La Tène period.

If we plunge into the comparatively unexplored wilderness of the Bosnian hinterland we find a number of sites along the Roman roads which often followed old tracks and which suggest the routes of penetration by which invaders entered. Some of these stations date back, like Butmir, to the neolithic time, while others exhibit a succession of periods.

Glasinac itself was on a plateau in a strategic position between the Adriatic and the Danube on the Roman road from Serajevo to the Drina.

Even with a map it is impossible to make these places more than mere names, all that can be done here is to note the existence of dozens of centres, at one of which (Sumetac) there was a hoard of objects typical of the Bronze Age in Hungary, at others there were plentiful examples of Hallstatt and La Tène industries, copper and iron mines, and hoards of coins.¹

In general the discoveries have been made along the river valleys most of which eventually find their way to the Save. The Drina, the Bosna, the Unna and their subsidiary branches have afforded much material, while the network of rivers has made communication fairly easy.

Four stations, two of them very well known, lie along the Bosna and its small tributary, the Miljačka, which rises in the plateau on which Glasinac is situated. On it, just before its junction with the Bosna, is Serajevo with its group of surrounding sites representing various periods; while on the Bosna itself are Sretes and Čatići in the Visoko district only a short distance from Serajevo.

In the valley of the Drina are Višegrad and Foča, with Pljevlje near by on the tributary Cehotina.

Near Jezero with its lakes, and the valley of the Pliva, famous for its falls, was Majdan rich in La Tène remains. The course of the Pliva to the Save is by the Urbas and runs through beautiful country.

Along or near the Unna are Ripač and Bihać, Jezerine, Drenovi Do and Debelo Brdo, with strata extending from the neolithic to the Iron Age.

The principal exception to the group of Save tributaries is the Narenta, which flows into the Adriatic. In its valley finds have been made at Imocki near Mostar, and Prozor, the latter on a small tributary river, while on the road from Ragusa to the interior at Bilek and Gacko rich burial fields have been discovered on the barren Karst.

One interesting feature is the existence near Serajevo of the ansa lunata common in the Italian terremare which survived in some sites of the Early Iron Age in Italy, including the Venetia district. This doubtless reached Bosnia via the Bronze Age stations of Ripač and Donja Dolina and spread also to various places in Serbia.²

Another link to connect the Balkan side of the Adriatic with the eastern coast of Italy is the white-filled incised pottery with spiral and meander designs belonging to the Bronze Age which is found along the Adriatic coast from Taranto up to near Pesaro, but is not known in northern Italy west of the Apennines. This ware occurs in the Bosnian-Serbian-Trojan area as early as neolithic times.¹

I have endeavored to show elsewhere² that in the prehistoric period the remains in the near-eastern district fell into four areas, one of which was the great zone along the Danube and its southern tributaries which extended from the regions north of the Adriatic as far as Troy, and even beyond into Asia Minor, and it is this area which shall concern us later, after a summary of certain important features of the Hallstatt culture and its affinities.

The great significance of Noricum as a distributing centre of the early Iron Age culture with its characteristic geometric designs particularly noteworthy in the earliest Hallstatt period, has been recognized for a long time; but additional interest and stimulus were afforded by the work of Professor Ridgeway, who, in his Early Age of Greece, identified the people from the head of the Adriatic who sent their branches southward into the peninsula with the Achaeans of Homer. Many who are unwilling to accept this identification have recognized the importance of the Hallstatt civilization which was diffused in various directions to many parts of Europe so that four local branches of it have been distinguished.³ The southeastern or Illyrian group extends from northeastern Italy around the head of the Adriatic to the valley of the Drav.

To say that all the Hallstatt people were Illyrian would be as absurd as to call them all Celts. The people who spread this civilization to various parts of central Europe were influenced by the earlier inhabitants whom they found in these districts, and one group might be called Illyro-Hallstatt, another Celto-Hallstatt, and so forth, from the natives with whom they mingled.

To assign any ethnical name to the people who occupied Hallstatt itself is more than the evidence at our disposal permits, particularly since the mixture of burials and cremations in the necropolis points to a fusion of peoples.

But while the racial identification is uncertain, some features of their art and customs afford striking resemblances to other peoples. The pottery, for instance, shows real analogy with the Dipylon funeral urns; despite differences in details they both are outstandingly geometric in character.⁴

Certain of the Hallstatt tombs suggest still more interesting connections. A rather rare type resembling the pozzi reminds Déchelette of the descriptions of the tombs of Patroclus and Hector. The custom of veiling the urns, mentioned in the Iliad, is illustrated by French tombs of the Hallstatt period in which bits of fabric were found placed over the urns.

The comparatively late funerary mounds of eighth-century Greece connect via Bosnia with those of central Europe and Gaul, the latter of which are exactly like the tombs of the late Bronze Age, thus showing that the type of burial was an old one though not equally distributed. Cenotaphs occur in Burgundy and elsewhere in France; they were common in Greece and Rome and may be traced back as far as Homeric times.

The literary evidence for the Homeric period has been substantiated by the discovery by Schliemann of several near Ilium and on the Thracian side of the Hellespont, and they were so common in Thrace that there is some difficulty in regarding them as honorary dedications.¹ Taken alone they may not signify much, but they afford one more link between Troy and the Adriatic by way of Thrace.

Another connection may be traced through the Illyrians themselves, although here we are on unstable ground, because the name first appears in the fifth century and the ancients did not always agree on what the name meant in either the geographical or ethnological sense.

We need hardly emphasize the kinship between Illyrians and Veneti on linguistic grounds or traditional grounds, since the archaeological evidence has furnished sufficient proof, but according to Herodotus one branch of the Illyrians were the Veneti, and the Venetian proper names are said by philologists to be identical with the Illyrian.

The linguistic connections between Epirus, Dalmatia and southern Italy point, according to Fick, to a migration of Illyrians southwards on both sides of the Adriatic.² More significant for our purpose is the fact that one branch of the Illyrians was called Dardanian, the name of people in the Troad; their territory was bounded on the south by Macedonia and Paeonia and on the east by the Bessi.³

Other branches of this stock became masters of Illyria and Thrace, subdued the Triballi, whose country extended from the sources of the Strymon to the Danube, and continued their conquests into Pannonia, settled amongst the Vindelicians and Noricans, and occupied Istria. It is no wonder that these aggressive people, who seem to have dominated or absorbed their neighbors, were often confused with the Thracians.⁴

The Thracians are mentioned among the allies of the Trojans,⁵ and another bond was the cult of the Cabiri which was said to have passed from Phrygia to the Troad and the isles of Thrace. This must refer particularly to the famous sanctuary at Samothrace, the island used by Dardanus as a stepping-stone en route to the Trojan side.¹ We have already spoken of Antenor’s connection with Thrace through his wife.

Another noteworthy feature is the affiliation between certain north-Greek and Trojan proper names. This is true in general of a large number of names, and in particular of those of Antenor and his sons, many of which contain elements especially characteristic of Macedonia, Thrace and the regions of northern Greece.²

It remains to be seen what routes were open to invaders, explorers or merchants, and to search for any material remains that may serve as landmarks on the road.

Although the most obvious corridor is via the Danube, invaders from Thrace may have crossed the Balkan Peninsula from east to west and reached Illyria (or Bosnia) by a more direct though more difficult way.

I have pointed out in another connection the great importance of the Morava-Vardar trench as a means of communication between the Aegean and the Danube, and we have seen that at Nish and other places along the Morava and Danube ever since neolithic times there existed a culture more or less closely affiliated.³

That direct communication westward across the mountain ranges was exceedingly difficult, but that a circuitous route, northward to the Danube or Save, westward along the Save and southward up one of its tributaries was not only possible but practicable and well-used is clearly evident.

The successive rivers emptying into the Save are the Drina, Bosna, Urbas (or more accurately its tributary the Pliva) and Unna. From the Save highway the explorer could travel to the headwaters of these streams, and from the sources of the Bosna to the upper Narenta is an easy stretch, along part of what is now the projected railway line from Spalato on the Adriatic to the lower Danube via Nish.⁴

The invaders must have found their way early up these rivers since the neolithic remains are so plentiful, but as Bosnia and Herzegovina were off the main line of traffic from east to west they continued in the neolithic period long after their neighbors had passed into the Bronze Age.¹

There seems to have been no true Bronze Age in Bosnia itself, but with the establishment of the iron industries at Hallstatt the old route came into use again, only this time the movement appears to have been from west to east and south.

As the Romans learned, the one way to hold Dalmatia safe was by defending it on the north. Without Noricum and Pannonia it was impossible to guard against invaders, and the campaigns of Tiberius and Drusus described by Tacitus, or still more familiar to us from Book IV of Horace’s Odes, show the soundness of the military strategy which secured these provinces.

The remains of the Early Iron Age in Bosnia do not show as long and continuous a development as those in Hallstatt or the Venetian district. Bosnia affords abundant examples of neolithic culture and there is no doubt that communications existed in the Danube valley from an early period, but the Early Iron Age seems to have been disseminated from the region of Noricum.

The crescent around the head of the Adriatic is so intimately connected with the two sides, and the remains are so homogeneous and so closely affiliated with Hallstatt itself that we can hardly accept Vergil’s statement that Antenor cruised along the Illyrian coast and reached Italy in that way.

Even if we admit that he and his followers came by sea, they certainly did not sail around the Peloponnesus and up the length of the Adriatic, but must have gone by land to Bosnia and taken ship from its coast. But no remains of the Early Iron Age have been discovered on the coast of Bosnia, and the narrow fertile Mediterranean strip south and west of the mountains is exceedingly difficult to reach from the interior.

The internal communications of the back country are easier than crossing the ranges.² The places on the coast of Italy where Venetian remains have been found extend only as far as the Isonzo, thereafter they lie inland.

“The Danube avenue, immemorial highway . . . . led straight to the mountain door of the Venetian plains.”³

Abandoning the Danube itself and following its tributary, the Save, the easiest route lies over the Peartrée Pass to the Adriatic.⁴ It lay between two natural thoroughfares, the level plains of northern Italy and the wide plain of the Danube, and was a starting point for the trade-route between the Adriatic and the Baltic.

It was situated at the head of navigation on the Laibach-Save-Danube system, while on the other side of the pass the Wipbach (Frigidus) took its rise and descended to the coast not far from the Isonzo and Aquileia. The route by water was interrupted for only a short stretch over the comparatively easy pass. None of the other routes offered so many advantages.

That from Trieste via Lacus Lugeum to Nauportus was steep and difficult and there was almost no water on the Karst plateau to carve out a river valley to follow. Moreover it did not connect directly with the fertile plains of Venetia. The more westerly passes which crossed the saddle between the Julian and Carnic Alps and entered Italy by the Isonzo or the Tagliamento were more roundabout, although the Romans utilized them and we have already noted the pre-Roman remains in the Isonzo, the Piave and other valleys still farther towards the west.

The ancients believed that a river connection existed between the head of the Adriatic and the Danube. Pliny tells us that the Argonauts sailed up the Danube and the Save to the head of navigation on the Laibach, where they built a settlement called Nauportus because the Argo had been carried across the mountains on men’s shoulders to the Adriatic.¹ There is nothing impossible in the story, and doubtless some Greeks who took such a route made a portage over the pass and were identified with the Argonauts.² Antenor himself may have followed the route.

The evidence thus shows that there is nothing intrinsically impossible in the story of a migration from Troy along the Danube valley. It has shown also that the remains in Venetia are part of the same group as those from Illyrian and Bosnia and that both are offshoots of the Hallstatt civilization.

This itself appears to be composite in character, partly European geometric, partly linked with more easterly traditions. The so-called oriental influences which appear in the late Hallstatt and La Tène civilizations are some of them a reintroduction of elements which had survived in a sort of subterranean fashion below the geometric Hallstatt phase.

One noteworthy feature is the meagre representation of the Bronze Age in the Danubian area. North of the river it flourished, especially in Hungary, but the remains along the Danube and its southern tributaries belong chiefly to the neolithic and iron ages.

While the great Bronze Age of the Aegean developed, this area remained in a stage of civilization in which the use of metal was very infrequent, and the influence of the Minoan world can have reached here only in its last stages. Troy did not send Antenor as a missionary of the culture which flourished there in the Late Minoan Age.

On the contrary, the energetic Iron Age of Hallstatt had already begun to make itself felt in Troy as the remains in the seventh city show, and evidences of its spread along the Danube and of the reciprocal influence from Ilium westward are clearly discernible.

This homogeneous though varied civilization of the Danube valley, the Hallstatt area and its branches on the two shores of the Adriatic, points to a connection between two important stations widely separated, namely Hallstatt and Troy, and the story of Antenor seems, as far as the archaeological evidence is concerned, to rest on a firm basis.

It would be more difficult to explain why Antenor rather than some other hero of the Iliad was chosen for the rôle, when and how the post-Homeric legend arose, what happy inspiration or lucky guess lit upon the connection between Troy and Venetia. The real problems seem to lie in the literary version, for the material remains have almost indicated the very milestones along the route of the adventurous hero who led the fugitives to new homes in the west.

IDA CARLETON THALLON

VASSAR COLLEGE,

POUGHKEEPSIE, N. Y.”

Map of Thallon Antenor on page 57:

Footnotes and references

Part 1

1 Strabo, XIII, 1, 53.

2 Paus. X, 27, 2.

Part 2

¹ Il. II, 150 ff.

² Liv. I, 1.

³ Il. II, 819–823; XII, 99–100.

⁴ Il. III, 122–124; Paus. X, 26, 3.

⁵ Il. XIV, 463–489.

⁶ Il. XVI, 342–344.

⁷ Il. XV, 516–517.

⁸ Il. XX, 395 ff.

⁹ Il. XXI, 545 ff.

¹⁰ Il. XI, 59–60.

Part 3

¹ Pliny, N.H. III, 20, 133–134.

² Serv. ad Aen. I, 242.

³ See e.g. C. Foligno, Padua (Mediaeval Towns), pp. 177–178 and illustration on p. 27.

⁴ Tac. Ann. XVI, 21; Dio Cass. LXII, 26.

⁵ See Furneaux, Tac. Ann. ad loc.; or Oxford text.

⁶ Il. XXIII, 653–699; Arg. II, 25–97; Aen. V, 361–484.

Part 4

¹ Pliny, N.H. III, 18, 126–128; 19, 129–132; Strab. V, 1. See also Nissen Ital. Landeskunde, I, pp. 488–493; II, Pt. I, pp. 211–225; Smith, Dict. of Greek and Rom. Geog., s.v. “Venetia.”

² Polyb. II, 17.

³ Liv. X, 2.

Part 5

¹ Strabo, IV, 4, 1.

² Hdt. I, 196; d’Arbois de Jubainville, Les premiers habitants de l’Europe, I, p. 301.

³ Piganol, Essai sur les origines de Rome, p. 78, and particularly n. 8.

⁴ Pliny, N.H. III, 19, 130.

⁵ Their importance in the amber trade, giving rise to the identification of the Po with the Eridanus of northern Europe; the sale of daughters by auction to the suitor bidding highest (Hdt. I, 196); fondness for black garments called mourning for Phaethon (Scymn. Ch. 396); their success in horse-breeding, said by Strabo to be the cause of their claim of descent from Antenor and the “horse-training Trojans” (V, 212, 215). This last pursuit is thought by some to be the result of conquests of Dionysius of Syracuse who kept a stud in the Po valley (Nissen, op. cit. I, p. 490). Against this view see the reference to Venetic horsemen as victors at Olympia in the seventh century (Alcman in Bergk, P.L.G. III, 834; Piganol, op. cit. I, p. 222, n. 5).

⁶ Dottin, Les anciens peuples de l’Europe, p. 234; Ripley, Races of Europe, pp. 257–258; Semple, “The Barrier Boundary of the Mediterranean Basin and Its Northern Breaches as Factors in History,” Annals of the Asso. of American Geographers, V, p. 46.

Part 7

¹ Liv. V, 33.

² Semple, op. cit., p. 32; Hodgkin, Italy and her Invaders, V, Bk. VI, n. p. 160.

³ Conway, New Studies of a Great Inheritance, pp. 190–215.

⁴ Déchelette, Arch. II, 2, pp. 529–540; Hoernes, Kultur der Urzeit, III, pp. 25–37; Peet, Les origines du premier âge du fer en Italie, R. Arch. XVI, 1910, II, pp. 378 ff.

⁵ Bertrand et Reinach, op. cit., Chapitre Deuxième I and IV.

⁶ Grenier, Bologne Villanovienne et Étrusque, passim.

⁷ Not. Scav. 1882, pp. 5–37, pls. I–VIII; ibid. 1888, pp. 1–42, 71–127, 147–173, 204–214, 314–380, pls. I–XIII; ibid. 1894, pp. 159–166 (Bassano); 1896, pp. 507–512 (Barbaria near Cologna Veneta); 1905, pp. 289–300 (Lozzo Atestino, Prov. Padua); Grenier, op. cit., p. 183.

Part 8

¹ Not. Scav. 1888, pp. 378–380.

² Montelius, Civilisation Primitive en Italie.

³ Déchelette, op. cit. II, 2, pp. 763–777.

⁴ Wide, “Nachleben Mykenischer Ornamente,” Ath. Mitt. XXII, 1897, pp. 233–258.

⁵ Déchelette, op. cit. II, pp. 524–525, n. 7 beginning on p. 524; pp. 755 ff.; II, 1, p. 426.

⁶ Grenier, op. cit. p. 337.

⁷ Ibid. pp. 365–414, ch. XI, “Les bronzes figurés,” particularly pp. 405, 408 ff.

Part 9

¹ Guida, II, p. 11; Hoernes, op. cit. p. 544.

² Conway, op. cit. p. 193; Guida, II, p. 73; Pellegrini, in Atti e Memorie R. Acc. Sc. Lett. Art in Padova, XXIII, pp. 209 ff.; 215 ff.

³ Conway, op. cit. p. 193; Hoernes, op. cit. p. 548; A. B. Meyer, Gurina in Obergaillthal; Baedeker, E. Alps, p. 510, map p. 512.

⁴ Baedeker, E. Alps, p. 258; Guida, II, p. 527; Hoernes, op. cit. pp. 175, n. 40; 550 and n. 237.

⁵ Hoernes, op. cit. p. 550.

⁶ Ibid. p. 550; Guida, II, p. 420.

⁷ Hoernes, op. cit. n. 97, pp. 519, fig. 4; 542, 547 ff.; 555, n. 247, 645; 449–450.

⁸ Ibid. p. 551 and n. 240 (see also index).

Part 10

¹ Munro, Rambles and Studies in Bosnia and Herzegovina, pp. 317–328 (summary of prehistoric remains); 129–160 (Glasinac); 160–172 (Jezerine); 89–127 (Butmir); 195–217 (Mostar and vicinity); see index for other places mentioned in text. The official publication is the Wissenschaftliche Mittheilungen aus Bosnien und der Herzegovina (Wien, 1893 ff.). See also Peet, “The Early Settlements at Coppa Nevigata and the pre-history of the Adriatic,” Ann. Arch. Anth. III, pp. 118–133; Baedeker, Austria-Hungary (which includes Bosnia and Herzegovina); A. J. Evans, “Antiquarian Researches in Illyricum,” Archaeologia, XLVIII (I), pp. 1–105; XLIX (I), pp. 1–167.

² Munro, op. cit. pp. 320–321; Peet, Ann. Arch. Anth. III, pp. 130–132.

Part 11

¹ Peet, op. cit., pp. 126–132.

² “Some Balkan and Danubian Connections of Troy,” J.H.S. XXXIX, pp. 185–201.

³ Hoernes, Kultur der Urzeit, III, pp. 54–64; Déchelette, op. cit. II, 2, pp. 588–591, 591–601 (oriental province); 601–606 (Hallstatt necropolis). Déchelette, op. cit. II, 2, p. 602, and Hoernes, Revue d’Anthr. 1889, pp. 328–336, believe the necropolis of Hallstatt is Illyrian and not Celtic. Bertrand, Arch. celtique et gauloise, p. 288, calls them either Celt or Celto-Illyrian.

⁴ Déchelette, op. cit. II, 2, p. 828, and n. 6; Grenier, op. cit. p. 229.

Part 12

¹ Déchelette, op. cit. II, 2, p. 633, fig. 243, p. 634, n. 1, p. 637, n. 1 (tombs); p. 638, n. 3 (veiled urns); p. 639, n. 1 (cenotaphs).

² Dottin, op. cit. pp. 151–153; d’Arbois de Jubainville, op. cit. I, pp. 301 ff.

³ Dottin, op. cit. p. 151, n. 9; Strab. VII, 5, and 7.

⁴ Dottin, op. cit. pp. 155–156. On the Thracians see ibid. pp. 156–164; d’Arbois, op. cit. I, pp. 265–299.

⁵ Il. II, 844.

Part 13

¹ Macurdy, Transactions Am. Phil. Asso. XLVI, 1915, p. 122.

² Macurdy, “The north Greek Affiliations of Certain Groups of Trojan Names,” J.H.S. XXXIX, 1919, pp. 62–68.

³ J.H.S. XXXIX, pp. 193–197.

⁴ Evans, “The Adriatic Slavs and the Overland Route to Constantinople,” Geog. Journ. XLVII, 1916, No. 4, pp. 241–261, map p. 259; Newbigin, Problems in Balkan Geography, Cvijić, La péninsule balkanique, pp. 17–25.

Part 14

¹ Munro, op. cit., p. 335.

² Evans, op. cit., pp. 241–243.

³ Semple, op. cit., pp. 38–46.

⁴ Ibid., pp. 32–36.

Part 15

¹ Pliny N.H., III 18, 128; Strab. IV, 6, 9; V, 1, 8; VII, 5, 2.

² Semple, op. cit., p. 36; Déchelette, op. cit. II, 2, pp. 562–570, p. 562, n. 3. For the Argonauts in Pola see supra, p. 25, n. 63.

Source

American Journal of Archaeology, Second Series. Journal of the Archaeological Institute of America, Vol. XXVIII (1924), No. 1. pp. 47-60. Material gathered by Artur Vrekaj. Translation, editing and publishing by Petrit Latifi.

The Tradition of Antenor and Its Historical Possibility

Author(s): Ida Carleton Thallon

Source: American Journal of Archaeology, Jan. Mar., 1924, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Jan. -Mar., 1924), pp. 47-65

Published by: Archaeological Institute of America

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/497572

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/497572?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms