Abstract

Between 1901 and 1944, Albanian villages in Macedonia and Kosovo were subjected to brutal invasions and atrocities by Bulgarian forces. This period saw significant violence, including massacres, forced labor, and the systematic destruction of Albanian villages. During World War I, between 1915 and 1918, Bulgarian troops carried out atrocities against the Albanian population, including massacres like the Starovo Massacre in 1913 and the killing of thousands of civilians. The second wave of Bulgarian occupation from 1942-1944 saw a resurgence of war crimes, including systematic starvation, theft of grain, and violent suppression of Albanian resistance. The invasions were marked by violence that not only targeted Albanian men but also brutalized women and children, including horrific instances such as pregnant women being pierced by soldiers. Despite significant loss and suffering, Albanian fighters like Bajram Syle Kurpali and Nak Berisha resisted Bulgarian forces, preserving the spirit of Albanian defiance during these dark times. The long-term impact of this violence remains underexplored in historical studies, with many atrocities and mass graves left undocumented until recent investigations.

Bulgarian-Albanian conflicts and Bulgarian atrocities against Albanians (1901-1944)

The Bulgarian-Albanian conflicts were a series of clashes and battles carried out between Albanian defensive forces and Bulgarian invasion forces in the years 1901-1944. Albanian villages in Macedonia and Kosovo were invaded and burned, and civilians were killed, by Bulgarian troops between 1915-1918, and again in 1942-1944. Bulgarian soldiers also carried out atrocities and war crimes, going as far as piercing pregnant Albanian women, similar crimes that Serbian soldiers had committed in 1912-1913.

Origin

The earliest signs of Bulgarian atrocities against Albanians may be stretched back to 1901. In this drawing, by Richard Caton Woodville Jr., we see the Cheta of the Bulgarian Slav lord Boris Sarafov, carrying off Albanian Villagers near Monastir.

Balkan War

The Starovo Massacre (1913): 72 Albanians murdered in the Mosque Courtyard by Bulgarian and Serbian troops

In March of 1913, at the time Western Macedonia was under Serbian and Bulgarian occupation, the Albanian village of Starovo near Ohri was the scene of one of the worst tragedies of those years. Bulgarian troops raided Starovo accusing villagers of “protecting rebels” and “not surrendering weapons”. The villagers who wanted to prevent bloodshed gathered at the village mosque with their women and children.

However, Bulgarian forces surrounded the mosque and forced the people to surrender. According to Ottoman archives and American mission reports, 72 Albanian men were removed from the mosque, lined up in the courtyard and shot dead. Among the victims were teenagers. A large part of the village burned down after the massacre; women, children and the elderly displaced.

Starovo became one of the symbols of violence against Albanians in Ohri region in 1913. Even today the names of those killed that day are found in the old cemetery of the village. Although forgotten for many years, the Starovo Massacre has been detailed in the international archives; it is considered as one of the most painful and darkest pages in the history of the Albanian people.

World War I

In World War I, Bulgarian troops massacred 50,000 Albanians in Kosovo and thousands of others in Macedonia. Thousands of Albanian starved due to Bulgarians stealing Albanian villagers wheat.

An Albanian kulla (tower) in Herticë of Podujevo where grain was stored in the cellar below, so that the Bulgarians would not find it.

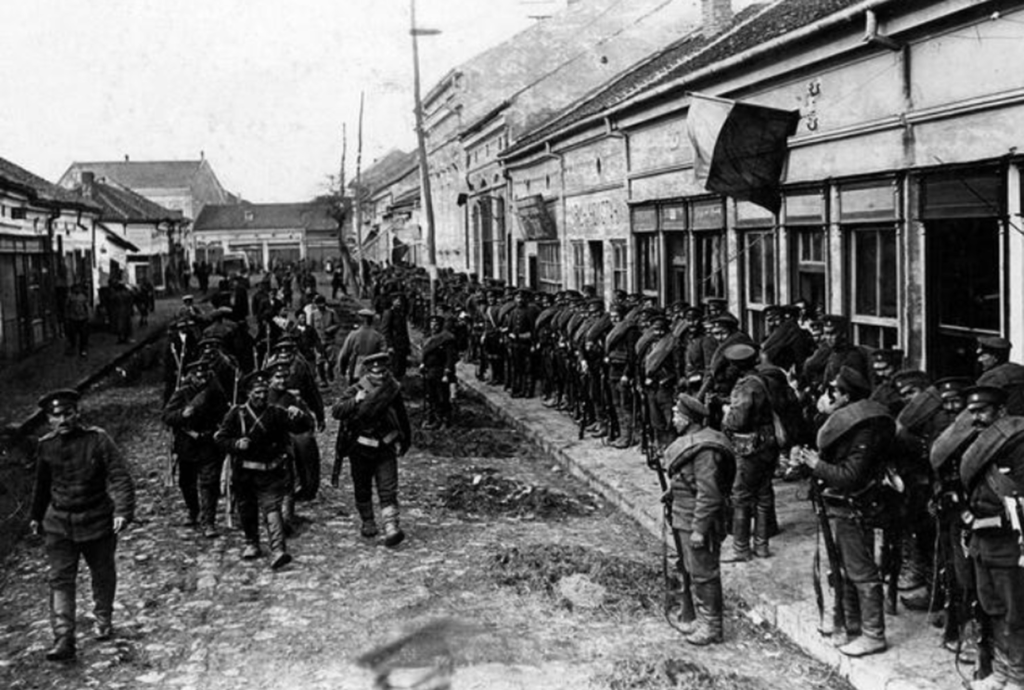

Bulgarian troops in Prizren, 1915.

On October 22, 1915, Bulgarians occupied the Albanian city of Shkup.

Albanian resistance

Albanians prepared for war with Serbo-Bulgarian gangs in 1915-1916.

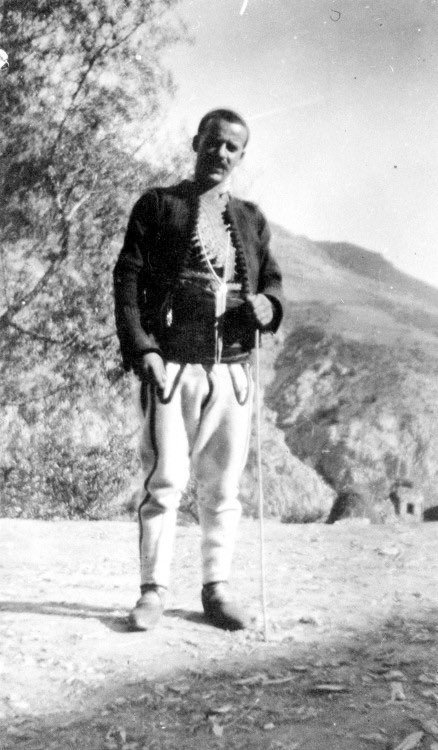

Bajram Syle Kurpali was one of the famous Albanian fighters who resisted the Bulgarian invasions. In 1916, despite severe injuries, Kurpali continued to fight Bulgarian forces in Kumanovo. By this time, he had been wounded 12 times.

In 1916, the Albanian Bec Sinani from Llap resisted the Bulgarian-Serbian forces who killed Albanians with knifes. Another who fought the Bulgarian troops were Nak Berisha. Idris Seferi, who resisted the Serbian invaders in 1912-1913, also resisted the Bulgarian invasion forces of 1916-1918.

Albanians from Shtirovica, Macedonia. Displaced by the Bulgarians in 1916.

Bulgarian atrocities against Albanians (1914-1918) – Part One

Although today we commemorate the 100th anniversary of the beginning of World War I and the numerous massacres committed against Albanians, the younger generations of Kosovo have remained uninformed and do not know where the remains of their great-grandfathers from that time remained and where they lie, because none of the historians of Kosovo has researched and dealt with such a bitter event.

From the sources and literature consulted, we see that not only the Balkans but all of Europe, in 1914, was a large powder keg, in which many fuses had been inserted. One of these fuses was Albania, says historian Michael Schmidt-Neke, who analyzes the Albanian political and social circumstances during World War I. He says that World War I began in the Balkans and not only because of the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, but because the Balkan Wars of 1912-13 were a kind of preparatory phase and test for the beginning of this war.

None of the Albanian historians has written about the Albanians who remained in Kicevo and their graves there.

In 1990, the Academy of Sciences in Tirana published a book with a summary of scientific works by Albanian and foreign authors entitled, “The Truth about Kosovo and Albanians in Yugoslavia”, where the works on Kosovo in the years 1912-18 include: Zekerija Cana, Zamir Shtylla, Marenglen Verli, Limon Rushiti, Ali Hadri, Hakif Bajrami, and none of them mentions the forcible sending of Albanians to Kicevo, the forced labor (Kolluk) in the construction of the Gostivar-Kicevo railway and the murder or death from hunger and disease of a very large number of Kosovars in Kicevo. Then their graves that are still there today.

In December 1991, a symposium was organized in Skopje, attended by scientists from all Albanian lands, and their papers were later published in 1994 under the title “Albanians of Macedonia”. In this symposium, for the years 1910-1918, the following authors referred: Limon Rushiti, Avzi Mustafa, Halim Purellku, Marenglen Verli, Zamir Shtylla, Fatmira Rama, whose works were also published in the book that came out on this occasion, “Albanians of Macedonia”, where we find nothing about the Kosovar graves in Kicevo from the time of the “First Bulgarian”.

Surely, due to the lack of sources, these authors also do not mention or give us any information about the Albanians sent and remaining in Kicevo in the years 1915-1918. It is strange that Havzi Mustafa and Halim Purellku, who were born and raised in Kicevo, in their references on this occasion do not provide any data or information obtained from the local population about the Kosovar graves.

Limon Rushiti, in his work “Political-Social Conditions in Kosovo, 1912-1918”, published in 1986 in Pristina on page 184, wrote only 10 lines about the construction of the Gostivar-Kicevo railway and the participation of Kosovars there. He is very realistic when he says that due to the lack of data, he was unable to provide more details about the events in question, and we at that symposium would have had the right to ask him how it is possible that he, as a Kosovar, does not have any data from the field (Kosovo) and the traditions of the elders in Drenica who spoke incessantly about the men they had left behind in Kicevo.

What do foreign authors say about Kosovo under the First Bulgarian?

On October 11, 1915, Bulgarian Prime Minister Vasil Radoslav proclaimed Bulgaria’s entry into World War I on the side of the Axis and argued for the necessity of an alliance with the Central Powers, which he saw as a way to protect itself from the attack of Serbia, which was an ally of Russia and the main power in the Balkans.

Esat Pasha Toptani, who came from Italy to Niš and after the help he received from Pashiqi together with his mercenaries from Dibra arrived in Durrës, where he declared himself the head of the “Provisional Government”.

Bargaining also began around Albania, promising the Balkan states a part of the Albanian lands. For these reasons, Greece, Italy, Serbia and Montenegro attacked the Albanians from all sides. But after the capitulation of Serbia and Montenegro, Austro-Hungarian and Bulgarian forces entered Kosovo and other Albanian territories.

The Bulgarian occupation zone included: Podujevo, Prishtina, Drenica, Ferizaj Prizren, Presevo, Gjilan, Kumanovo, Skopje, Tetovo, Gostivar, Dibr, Kërçovë, Struga, Ohrid and Prespa. A large number of Albanians from Kosovo, bound like animals and under the dictates and torture of Bulgarian soldiers, were sent to Macedonia and Bulgaria, never to return from there.

With the capture of Skopje and Kumanovo by the Bulgarians, Serbia was cut off from all lines of communication, as well as the hope of joining the Allied troops in Greece. The Austro-German troops had occupied Belgrade and were rapidly advancing south. The only direction for the withdrawal of the Serbian army was the territory of Kosovo, to cross into Albania and from there into Montenegro.

On 19-21 November, the first battle in the territory of Kosovo between the Serbian and Austro-Hungarian armies was fought. Serbia, it seems, had been avenged by the Albanians for the numerous massacres it had committed against them and lost the battle against Austria-Hungary, where a large number of Serbian soldiers were killed.

After winning this battle, Austria-Hungary, through the Ibar valley, penetrated Kosovo without major fighting. The Supreme Command of the Serbian Army on November 21, 1915 ordered the withdrawal of the Serbian army through Peja-Gjakova-Prizren, towards Albania, in a very cold winter and very difficult terrain, where a large number of soldiers were killed, which happened later the Serbs told and transmitted from generation to generation with the words “Niko we zna shta su muke teshke, ako nije preshao Albaniu peshku” meaning “You can’t understand what a heavy toil is, if you have crossed Albania on foot.”

The Serbian author, Janiće Popović, in his work, “Kosovo u ropstvu pod bugarima, 1915-18”, published in 1921 in Leskovac, writes that Pristina fell into the hands of the Bulgarians, Germans and Austro-Hungarians on the same day, November 23, 1915 at 2 p.m. The Bulgarian army entered Pristina from the southeast, the German army from the northeast, from the direction of Llapi, and the Austro-Hungarian troops from the north – the direction of Mitrovica.

Krste Bitovski, although of Slavic origin, was honest in his article entitled “Glad, Stradanja i otpor stanovishtva Kosova i Metohija za vreme bugarske ocupacije”, published in “Istoriski Glasnik”, no. 4, Belgrade, 1963, he writes that “The Bulgarians considered these Albanian territories as an integral part of Bulgaria and the majority of the administrative apparatus was made up of people brought from Bulgaria, although in some villages the local Albanian population was also used.

In the Albanian municipalities of Kosovo that were under Bulgarian rule, there were also people who collaborated with the Bulgarian occupier for personal interests, he says. The Bulgarians included the local element in low administrative positions or in the police bodies for propaganda purposes and to gain the trust of the uneducated masses, supposedly considering them equal to the Bulgarians, while on the other hand, murders, reprisals and internment continued and were a regular occurrence.

Theft of grain

The first and immediate action taken by the Bulgarians after the occupation of Albanian lands was the order to collect all the grain from the producers and place it in Bulgarian military warehouses, supposedly to be paid for, but it was never paid. In this way, an artificial bread crisis was created, where hunger began among the poor population, especially in the first months of 1916, where in a letter from the governor of Ferizaj it is stated that in the municipality of Shterpce and its surroundings, more than half of the population feeds on pumpkins, especially the families of people killed or mobilized by the Bulgarian army and sent outside Kosovo.

There, the governor writes, people of different ages had died and are dying every day from hunger. The above-mentioned author Kërste Bitovski in his article, p. 84 presents and analyzes the letter of the Nachalnik, which emphasizes that the population, in the absence of grain, is forced to slaughter their livestock to save themselves from death, but by eating only meat, they become even more ill.

This phenomenon was common to all those countries that were under Bulgarian occupation. It is worth noting that the suffering for bread was also present in those villages, whose land was of very good quality, because even though grain was produced, it was taken by the Bulgarian army. The poverty was also helped by the forced mobilization of men who were the main force of physical labor and the internment and forced labor-kulaks outside Kosovo.

Janacije Popovic in his work, “Kosovo u ropstvo pod bugarima”, 1915-1918, published in Leskovac, 1921, notes that the summer of 1917 was so dry that no grain was produced in the entire territory of Kosovo, especially corn, which did not yield at all. In the territory of the Pristina district, he writes, not a single water mill was working due to the great drought where all the rivers had completely dried up and the daily food of the population was reduced to a handful of flour, boiled with nettles and various herbs. The misery had reached such an unbearable level that death was considered a very happy opportunity to escape this torment.

Other factors also had a great impact on the impoverishment of the population, such as the kullak – forced labor of men with carts and draft animals, then the internment in various camps outside Kosovo, in order to prevent the population from organizing and rising up in any uprising.

The largest and most difficult works, by means of the kullak (forced labor) where a very large number of the population even lost their heads, were the works on the construction of the narrow-gauge railways, Gostivar-Kirchevo, and Veles-Prilep.

In the construction of these railways from the end of 1915 and the beginning of In 1916, the Albanian population of Kosovo was engaged with all the carts and draft animals, but also without them. Kosovars also participated in forced labor in the construction and maintenance of various roads in Kosovo and Macedonia for military needs, where thousands of Kosovars died of hunger, disease or were killed, which modern Albanian history has little or no mention of.

Krste Bitovski and Janaqie Popovic, quoted above, have presented letter no. 43 of the military inspection of the Province of Macedonia from 1916-17, where it was stipulated that railway workers would be given bread and paid 1-2 kilograms of flour per day. But this remained only on paper because payment in flour was never made and there was no regular bread to eat, and this was the most frequent cause of death for people who worked forced labor on the railway.

Bulgarian troops beating Albanian workers

The population working on the railway and road maintenance, according to the order of the above-mentioned inspectorate, had to be far from their settlements and homes so that they could not escape and leave work. The work began with sunrise and ended with sunset, under the strict and continuous supervision of Bulgarian soldiers, who constantly beat the workers with sticks, writes the cited author.

Dr. Zhivko Avramovski, in his work entitled: ,,The Austro-Hungarian-Bulgarian conflict over Kosovo and Bulgaria’s intentions to reach the Adriatic Sea through Albania ,, (1915-1916), published in Gjurmime Albanologjike III, 1973, Prishtina, pages 102-181 and Dr. Limon Rushiti, cited work, page 184; emphasize that the living conditions of Kosovars under the Bulgarian occupation were so unbearable that it is impossible to put all the events on paper, especially since we have not had the opportunity to see and analyze all the archival documents that may exist in the various archives and, not having sufficient data, we have only superficially mentioned the various events, without going into details, say the aforementioned authors.

Dr. Bogumil Hrabak and Dr. Dragoslav Jankovic, in their work, “Srbija 1918”, Belgrade, on pages 102-103 note that the Bulgarians placed selected military forces in the territory of Kosovo because Kosovo was considered a very important strategic place where the Bulgarian military bodies exercised their unlimited power.

The position of the Bulgarian army in Kosovo and Macedonia is also given in several reports of the Kosovo Committee, which reports were written at the time of the events when the Bulgarian army was committing great atrocities against the Albanians in Kosovo and Macedonia. The aforementioned report is found in the Albanian Central Archive-Tirana, file 25 document 50744, where it talks about the numerous murders and robberies in Skopje and Prizren, about the rape, abuse and mistreatment of Albanians everywhere.

Bulgarian atrocities against Albanians (1914-1918) – Part Two

Field research data for the Kosovar Graves in Kicevo killed by the First Bulgarian

In the winter of 1974, more than 40 years ago, I was a guest in the village of LLoçan, municipality of Deçan – Kosovo, at the Rexhe and Binak Stojkaj family. In the “Men’s Chamber”, which was on the third floor of the tower, the old man with a long mustache and sitting cross-legged, when he realized that I was from Kicevo, said to me: “….Kicevo has raised many men for us”.

Not understanding what was being said, I asked in confusion: “How did that thing happen, Binak? Sefer Zajazi, Nezir Koxha and Kalosh Dan’s Kicevo, the descendants of Sylë Vokshi, Mic Sokoli, Azem and Shotë Galicë, ate it.” You are young and you don’t know those things, but since you have entered school, you will learn them all…

A year later, I happened to be a guest in the villages of Bajicë and Damanek in the Municipality of Gllogovc (Drenica). Haxhi Hamza Zariqi from Bajicë also complained to me and told me in the same conversation that at the time of the “first Bulgarian”, the remains of many Kosovars had remained in Kicevo.

In the summer of 1975, when as a student of History at the University of Prishtina, I had taken exams with Zef Mirdita, Emin Pllana, Ali Hadri and Muhamet Ternava; and I had completed my second year, I had not yet heard any of the above-mentioned professors, even in a casual conversation, mention the Kosovars who remained in Kicevo.

I remained hopeful that in the following years the professors would lecture on the history of the more recent period and perhaps in the last year of studies Skender Rizaj, Shukri Rrahimi, Masar Kodra, Qamil Gexha and others would give us a lecture about Kosovo under the first Bulgarians and the remaining of many Kosovars in Kicevo.

Bulgarian soldiers murdering Albanian workers

During the summer holidays of 1975, in my Kicevo I met and talked with some of the oldest and most well-known elders of Kicevo about the Kosovars who remained here in Kicevo. Elder Izer Doga explained that Kosovars were brought here, treated as prisoners of war and worked on the construction of the small railway Gostivar-Kirchevo, where some died of fatigue, disease and hunger, and some were killed by the Bulgarian soldiers themselves who guarded them day and night.

Ali Ramë Dedja, who at that time had 2 mills to grind grain, said that at each mill, there were constantly guards from the Bulgarian army and it was impossible for anyone to bring the grain and grind it in the mill. Even the local population was forced to eat the little corn that they were able to hide from the Bulgarians without grinding it, boiling it in a fire or even grinding it with “bunguri stones” in a primitive way.

Ali Rama said that the village priest, Mulla Ramë Dedja (died 1950), often told the story of the Kosovars in the village mosque when the villagers went to pray the Friday prayer. During the time of the “First Bulgarian”, the priest said, many Kosovars who had been brought as prisoners of war to work on the old railway were killed or died of typhus, hunger and exhaustion. Some were buried by the Bulgarians while they were still alive, and some who were sick with typhus were piled up, covered with straw and set on fire.

The famous man of the village of Drogomishtit i Vogël – Idriz Rrushaj and his grandson, the very well-known teacher of this area, Baftiar Rrushaj, had told me what their grandfather had told them that there were Kosovars buried in the old cemetery in the middle of their village.

After returning to the faculty and continuing their studies, in the last two years, the professors lectured us about the First World War, but none of them gave us any information about the remains of Kosovars in Kicevo or in other cities of Macedonia or Bulgaria, explaining that the archival documents are found in Sofia, Rome, Belgrade, Berlin and Vienna where until then no one had gone to find and research them.

In the meantime, due to the effort of researching the events in question and continuing the investigative work in the field and the population, as well as for other illegal activities, I was imprisoned in Kicevo and sentenced to 4 years of heavy prison by the Court of Çark-Skopje.

After leaving prison, perhaps out of fear and the trauma that “Idrizova” had left me, I neglected the graves of the poor Kosovars and their century-old legacy in Kicevo.

To my great luck, in May 2009, officials of the “Osllome” municipality informed me that in the village of Jagoll in Kicevo, someone, wanting to level some of their own land, had come across some very old graves. I visited the terrain and was convinced that it was a tumulus cemetery from the late Illyrian period, a time when the Illyrians were under Roman rule. I begged the landowner not to level the cemetery and that we would continue to conduct archaeological excavations in this locality.

The same day, near the Illyrian cemetery, while talking to the 90-year-old old man of that village – Haxhi Ademi and explaining to him that the discovered graves were very old, he asked me if I was informed and if I knew that there are several Kosovar graves above the village that date back to the time of the First Bulgarian Empire.

This news came to me like a bolt from the blue, because the words of the old man Binak Stojkaj from Lloçan and Haxhi Hamza Zariqi from Bajica e Gllogovc were still ringing in my ears that many Kosovar men were raised by Kicevo.

We went to the place that the population called,,Kosovo Graves,, where we saw that the graves were old and covered with thorns, trees and oaks. Mixha Adem and other villagers who joined us later showed that there are also graves in Berikovo, Prapadisht, Tuhin, Haranjel; and everywhere where the old railway passed. They said that the local population itself, with the permission of the Bulgarians, had brought the bodies there and buried them, not wanting the soldiers to burn them in piles of wood.

Professor Ahmet Mora, born and raised in the village of Jagoll, was told by his grandmother Rabie that even during the Bulgarian era, a pumpkin had fallen from a cart loaded with pumpkins and broken into several pieces. Two Kosovars who had been working on the railway had picked up the pieces of the pumpkin and eaten them quickly, uncooked, and had fled for fear that the guard would see them.

In May 2009, I went back to Zajaz and met the oldest elders of this area; Dautit Liles’ Xheza, Beqir Tufka, Bajram Meta’s Zyli, Osman Tufka, Lez Beshku], Qamil Meta’s Medini, Ali Abdulla Shehu who told me the same words that the 90-year-old Haxhi Ademi had told me; then the English professor, Ahmet Mora, the Albanian professor, Nazif Selimi, the Geography professor, Qamil Fejza, the historian Ismet Selimi, all from the village of Jagoll, municipality of Kërçovë.

Graves of the Albanians killed by Bulgarians

The elders of Zajaz also showed me some of the places in Zajaz and the surrounding area where there were Kosovar graves: at the graves of Babuneci, at the hill of Xha Lila, behind Xha Xheza’s hut, at the graves of the Tufkallari, at the hill of Kolibari-near Sateska, Llapkidoll-down near the railway, Trapçindoll-near the Gostivar-Kërçovë road.

Beqir Tufka, Xha Xheza and Ali Dedja explained that the local population was forced to send a little bread to the Kosovars. Each neighborhood of Zajaz had a designated day to send bread to the railway, and the piece of bread did not dare to be larger than a cigarette box. If someone tried to give someone more, the Bulgarian guard killed both the one who brought the bread and the one to whom the bread was given.

The same people who sent the bread took the bodies of the dead Kosovars and brought them to bury somewhere in the existing graves of some neighborhood or village, on the edge of the existing cemeteries that have not been forgotten from generation to generation, but have been preserved and remembered with a special and significant name: “Graves of Kosovars killed by the first Bulgarian”.

Regarding this event, I also consulted the imam of the village of Drogomisht i Vogël – Mulla Ali Ademi, who repeated to me the words of his father – Hamdin, as well as the words of the old man Idriz Rrushaj that in the middle of the village of Drogomisht i Vogël, at a place called “Juria”, there are also Kosovar graves from the time of the First Bulgarian Empire. Sami Fejza, the son of Muadin Fejza from the same village, says that father Muadin had told him that there were over 50 Kosovar graves buried there during the time of the Bulgarian Empire, which erosion had flattened.

But how many Kosovars there must have been, I wondered. How many graves were left in these Albanian lands, starting from the Uprising against the Tanzimat, the war led by the League of Prizren, the Uprisings of 1909-1910-1911-1912, the Serbian massacres of 1913, the two Balkan wars, World War I, the Kaçaka Movement between the two wars, World War II, the war against Tito-Ranković, the war against Milošević. How great and how strong this people was. To leave graves in all four corners of the country and yet manage to stand up to a bloody Serbia, for years.

Archival sources for Kosovar graves are lacking, but as a historian I can state with full responsibility that History as a science, in addition to material and written sources, also accepts oral sources collected in the field, even old songs, ethnographic data, toponyms, etc.

And how could written archival sources not be lacking, when it is known that no conqueror has recorded how many Albanians he killed and how many mass graves he filled with Albanians. The plan of “Naçertania” was to eliminate this race, which is the oldest in the Balkans, and there was no need for anyone to record and record it, so that we would have archival documents today.

I, Ilmi Veliu, Doctor of History and Director of the Kicevo Museum, announce and inform you that based on field data and information I have received from the local population in the last ten years, I have discovered and located many cemeteries where the remains of Kosovar Albanians lie, which need to be arranged, marked and visited by all the grandchildren or great-grandchildren left behind, and who today have managed to live in a free Kosovo, in that Kosovo for which those Kosovars who today were sent to Kičevo died.

World War 2

In World War II, thousands of Albanians were killed, beaten and tortured by Bulgarian forces in both Macedonia and Kosovo. More on that in this article here.

Sources