Written by: Shasivar Kabashi. Translation Petrit Latifi

Abstract

The text examines Et’hem Pasha’s role as commander-in-chief of the Vilayet of Kosovo (1889–1890) amid severe ethnic tensions, border disputes with Montenegro, and internal Albanian unrest. Facing armed mobilization by Albanians over rumors of territorial loss, Et’hem Pasha pursued a cautious strategy combining diplomacy, restraint, and limited military reinforcement to prevent escalation and international repercussions. Through negotiations with tribal leaders, reassurance, and coordination with Ottoman authorities and Montenegro, he successfully de-escalated the crisis and avoided war. Despite lingering tensions and later conflicts, his actions temporarily stabilized the border and earned him high Ottoman recognition.

Cross-border tension between the Albanians and Montenegrins in 1890

Et’hem Pasha, a career general, after only two weeks as commander of the Redifs in Skopje, on July 23, 1889, was appointed commander-in-chief of the Vilayet of Kosovo. And this was not an easy task at all, because the vilayet in question was already experiencing ethnic tensions and cross-border clashes since the decisions of the Berlin Congress. The Albanians who had already woken up from their sleep because the danger had knocked on their door and seeing that the Istanbul government was no longer able to protect their borders, had begun to take their own destiny into their own hands.

But, in addition to the cross-border tensions that existed, Kosovo at that time often experienced clashes between Albanian tribes, and administrative problems from tax collection were not uncommon. And upon taking office as the new commander, in September of that same year he was faced with the people of Drenica who did not pay their tribute. On June 14, 1890, he was to leave urgently for Peja, since in the border areas with Montenegro, the Albanians of Peja and Gjakova had already gathered there, armed, where together with the highlanders of Rugova they were threatening the Montenegrin border.

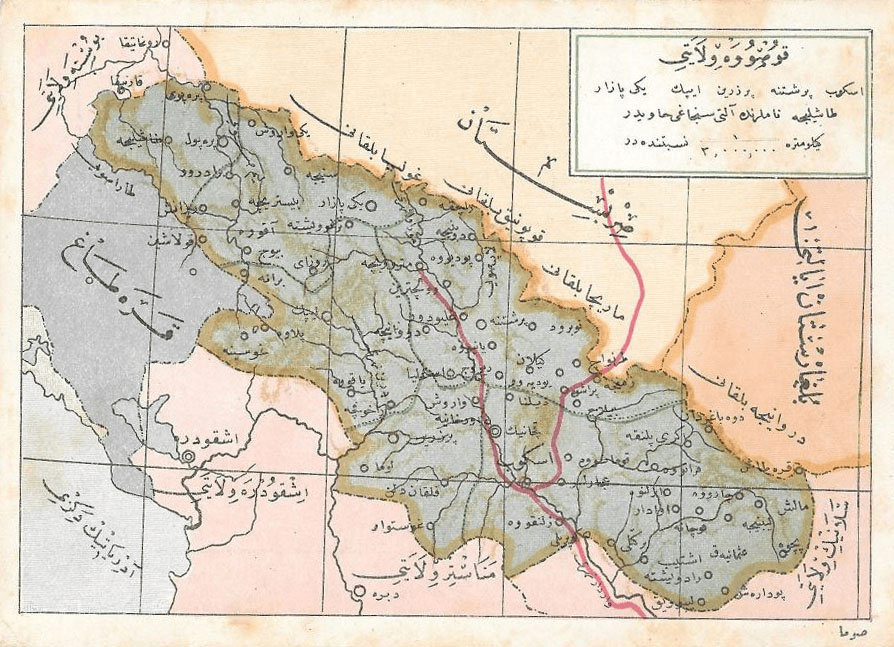

Map of the Vilayet of Kosovo

Found in such a situation, the commander faced a great challenge – on the one hand, he had to maintain the friendly relationship they had with the Montenegrin state, because if the opposite happened, the Ottoman state would be implicated in international problems, and on the other hand, he had to be as close and gentle as possible with the worried highlander Albanians.

Et’hem Pasha, knowing that a possible clash was very harmful to the Ottoman state, immediately began the preparations he needed for an urgent intervention, before the situation got out of control. On June 15, he requested through a telegram some necessary reinforcements that he needed for the parts of Rugova, specifying that 6 battalions of soldiers and a battery regiment were needed.

But, on June 26, at the request of Et’hem Pasha himself, these battalions did not move from Peja, because he considered that such a march of soldiers could be misunderstood by the Albanians and it was necessary to remove even the slightest suspicion among them – that the government was using force.

After Istanbul was informed very quickly by telegraph about this event, the Mabeyni was immediately convened, a body that had increased its powers during the reign of Sultan Abdylhamit II. This entire situation and this telegraph communication between Peja and Istanbul is found in the Ottoman Archives of the Prime Minister’s Office in Istanbul, where through this article we are giving a general overview of the event.

Edhem Pasha

On July 3, Mabeyni, after having gathered about this problem and having assessed that Ottoman-Montenegrin relations should not be damaged, due to the possible implications of the Great Powers that it could bring, had sent a talimat in the form of instructions to the pasha, on what he should do.

With what the pasha was obliged to do, the first point was the soft language and courtesy that he should use in meetings with the tribal leaders, to first understand the concern and the reason for the gathering at the borders, and only then, after consultations that he would have with the tribal chieftains themselves, to order a small reinforcement of soldiers and batteries to the border areas, so that the situation would not escalate.

After that, with the help of Mehmet Bey, who was the border commander, they would send an official to the Montenegrin side so that the Montenegrin highlanders who had gathered around the border would also retreat, and the problem would be solved by official representatives.

On July 4, the Pasha would officially receive the response from Skopje, which was the capital of the Vilayet, that the requested reinforcements would be sent – 3 battalions and a regiment of artillery battery. On July 7, 1890, with these reinforcements, Et’hem Pasha would arrive at the borders, where 5-6 thousand Albanians were waiting armed, as the pasha’s own telegram provides us with the number.

And on July 8, according to the telegram of the Mytesarif of Peja, the Pejans had begun to return from Rugova, and he attributed this to the work of Et’hem Pasha. Meanwhile, the pasha’s own telegram would arrive on July 9, 1890, stating that up to 7,000 Albanians had gathered around the border, and the reason for the gathering in this number was a rumor that had circulated that the part known as the Shekullari Meadows had been given to the state of Montenegro.

From the research that the pashas had done and the announcements they had made through telegrams, it had emerged that the part called Shekullari, which was owned by the Montenegrins, three-quarters of this part had been sold to the Rugovas, and for this reason, upon hearing such a rumor, the Albanians had mobilized immediately. Faced with such tension among the Albanians, Et’hem Pasha, guaranteeing that there was no such thing and trying to reduce the gathered crowd as much as possible, signed an agreement with the tribal chieftains, so that the others would return to their homes, and only 200 people would remain at the borders.

An interesting thing that had happened in this deal of the Albanians is that, during the stay of the chieftains at the borders, they had requested that they be paid for the expenses of the days they would stay there, for which the Minister of War had also approved such a thing. Thus, Et’hem Pasha had prevented a possible conflict with Montenegro, which could consequently bring implications for the European powers.

But, even though he had reached an agreement with the chieftains, Riza Bey Gjakova, with a large group of his men, had descended to Plave and Guci, since in the pasha’s telegram, he did not have good intentions and was trying to convince the nobility of these sides that they should go on the attack.

Not wanting to return without clearing the border of all Albanians, Et’hem Pasha had set off for Plav and upon reaching between Veliko and Plav, he had sent a letter to Riza Bey Gjakova, asking them to withdraw from where they had come, threatening them with the use of force if they did not.

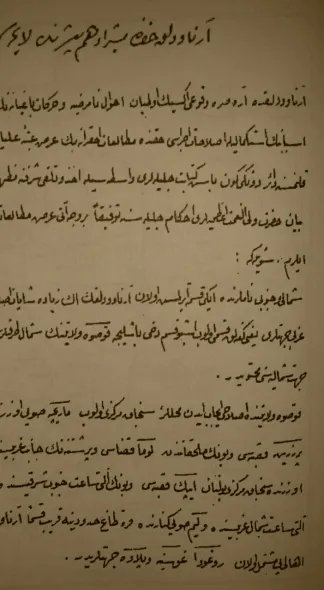

Facsimile of Et’hem Pasha’s report on the Albanians

After Riza Bey Gjakova and his men were convinced to return to their homes, the pasha, informing Istanbul of a calming of the situation, had requested that a meeting be arranged for him with the Prince of Montenegro himself, to reach an agreement on controlling the border line. After managing the situation as Mabeyni had requested, on July 17, 1890, the pasha was awarded the first decoration of the Ottoman Family, the “Nişan-ı Al-i Osmanî”.

While a mountain of documents preserve the archives of Istanbul about this clash, the Albanians preserve it in their folklore, sung with lutes and çifteli under the title of Hysen Bajri. This, a bajraktar of Rugova, brother of Kadri Bajri, a distinguished activist during the League of Prizren. According to the rhapsod, the clash of the hero of the song with the secularists is expressed in these lines: “Hysen Bajri has climbed the ladder, he shouted loudly, you bajraktars, don’t leave me, O secular man, my body has filled a full grave, my shoulders have been cut off with a scimitar”.

The Shekullari Valley, which today belongs to the Montenegrin state and consists of several villages, was the site of hostilities between Albanians and Montenegrins during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Even after Et’hem Pasha had achieved a truce between Albanians and Montenegrins during his tenure as commander-in-chief, as well as during his mandate as Vali of Kosovo, tensions and clashes on this border continued in the following years, until a significant part of these lands would be occupied by the Montenegrin state during the First Balkan War.