By: Fahri Xharra. Translation Petrit Latifi

Summary

This article discusses the extinction of the Dalmatian language and reflects on the broader issue of cultural and linguistic neglect among its descendants. The author emphasizes that Dalmatian, which disappeared with the death of its last known speaker, Antonio Udina (also known as Burbur) in the late 19th century, was not a Slavic language but a Romanized Illyrian one. Although Illyrian itself was never preserved in written form, traces of it survive through Latin records and place names, offering valuable insights into the region’s linguistic past.

The text highlights how Udina’s language was documented by scholars, yet his identity is often inconsistently described as Italian or Croatian, raising questions about how a family could retain a language already considered extinct. Through comparisons between Dalmatian, Italian, modern Albanian, and English translations of Udina’s recorded speech, the article demonstrates the linguistic continuity and historical importance of Dalmatian.

Ultimately, the author argues that a lack of scholarly engagement, especially in Albanian, has allowed others to shape the narrative of this heritage. The article aims to inform and encourage younger generations to pursue academic research on the Dalmatian language and related Illyro-Pelasgian remnants, contributing meaningfully to the understanding of regional history and identity.

Introduction

A very heavy question right at the beginning, even before the writing truly starts.

The more I study, learn, and discover, the further away I feel from my own nation—a nation that never found a moment of peace to look at itself today, to compare itself with the past, and to draw historical lessons, since history is the teacher of life.

We are so stubborn that we pretend to know a great deal, while in reality our knowledge is largely based on the “teachers” of our traditional gatherings and folk songs. These have tried, without factual grounding, to preserve the past in our collective memory. We are easily influenced by foreign propaganda and fall victim to informational confusion. Writing and scholarship we have left to others—to foreigners—who can then more easily manipulate us.

The Last Speaker of Dalmatian

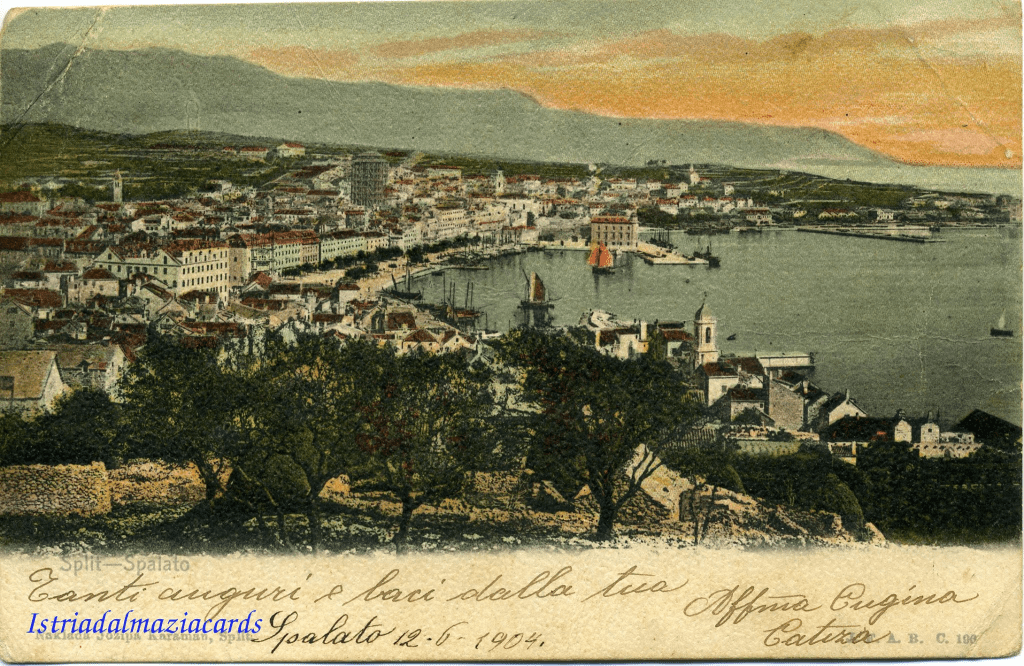

In 1887, the last person who spoke the Dalmatian language (Dalmatic) died. He lived on the island of Veglia (Krk) in Dalmatia and was named Udina Burbur.

According to this journalistic report, Austro-Hungarian scholars recorded his speech. The language spoken by Udina Burbur was not Slavic; it was a Romanized Illyrian language. Before Romanization, the Dalmatians certainly spoke Illyrian.

We do not possess written records of Illyrian, but through Latin many Illyrian words—especially toponyms—have been preserved, from which we can learn much about the Illyrian language.

(journalistic report)

However, the man mentioned is described as the last speaker of his family’s language; yet in various references he is presented either as Italian or Croatian.

How could an Italian or Croatian family have spoken the already extinct Dalmatian language? But we lack the time, the will, and the resources to deal with this Illyro-Pelasgian remnant—that is, with ourselves, who are already so few and diminishing day by day.

Recorded Dalmatian Text (by Prof. Ivo Antonit)

Before his death, Tuone Udaina – Burbur left behind the extinct Dalmatian language (Romanized Illyrian), recorded by Professor Ivo Antonit.

Original Dalmatian Text

Ju sai Tuone Udaina de saupranaum Burbur, de jein sincuonta siapto, feilg de Frane Udaina, che, cun che el sant muart el tuota, el avaja setuonta siapto jein…

(fxh: I do not recognize the accent of this language)

Italian Translation (for comparison)

Io sono Antonio Udina, col soprannome B., di anni 57, figlio di Francesco U., che, quando morì suo padre, aveva 77 anni. Sono nato nella casa numero 30, nella via che conduce alla chiesa, non lontana dalla mia casa: è distante dieci passi.

Quand’ero giovane, a 18 anni, cominciai a uscire di casa e a gironzare con certi ragazzi e ragazze; si stava in compagnia allegri e si giocava alle palle. Poi lasciai questo gioco e cominciai ad andare all’osteria a bere vino e a giocare alla mora; fino a mezzanotte e talvolta fino al mattino, tutta la notte, si stava insieme in dieci o dodici giovani. Poi uscivamo dall’osteria e andavamo a cantare sotto le finestre della mia amata…

Modern Albanian Translation

Unë jam Antonio Udina, me nofkën Burbur, 57 vjeç, i biri i Fran Udines, i cili ishte 77 vjeç kur i vdiq i ati. Kam lindur në shtëpinë me numër 30, në rrugën afër kishës, e cila nuk është larg nga shtëpia ime – vetëm 10 hapa.

Kur isha i ri, në moshën 18-vjeçare, fillova të dilja nga shtëpia me shokë për të bredhur me vajza dhe djem. Shoqëria jonë ishte e gëzuar dhe luanim edhe me top. Më vonë filluam të shkonim në kafene, të pinim verë, ndonjëherë deri në mesnatë, ose deri në mëngjes, apo tërë natën bashkë – 10 deri 12 të rinj. Pastaj dilnim nga kafeneja dhe shkonim t’u këndonim të dashurave nën dritare…

English Translation

I am Antonio Udina, known by the nickname Burbur, 57 years old, son of Francesco Udina, who was 77 years old when his father died. I was born in house number 30, on the street near the church, which is not far from my home—only ten steps away.

When I was young, at the age of 18, I began going out with friends, wandering around with boys and girls. We were cheerful company and played ball games. Later, we started going to taverns, drinking wine, sometimes until midnight or even until morning, spending the whole night together—ten to twelve young people. Then we would leave the tavern and go sing beneath the windows of our beloved…

Purpose of the Article

This article is purely informative and serves as guidance for younger generations, particularly to help them find meaningful topics for master’s-level academic research—to do something valuable for our history.

For those interested, there exists a fragment from the Enciclopedia Italiana and abundant scholarly literature on this extinct language. Only we do not have it in Albanian.

References

- Slobodna Dalmacija archive

- Lorenzo Renzi, Introduction to Romance Linguistics

- Giovanni Gobber, Chapters of General Linguistics

- Sextil Pușcariu, Studies in Romanian Linguistics

- Carmela Perta et al., Arbëresh Linguistic Survivals

- Carlo Tagliavini, DALMATICA, LINGUA, Enciclopedia Italiana (1931)

- Žarko Muljačić, Das Dalmatische (2000)

- Istrianet archives and additional academic sources