By Fahri Xharra. Translation Petrit Latifi

In the nationalist historiography of the Western Balkans, the thesis that the medieval Orthodox churches in Bosnia, Herzegovina, Kosovo, Dalmatia and Croatia represent evidence of an uninterrupted Serbian presence since the Middle Ages has been widely spread. This article argues that this claim constitutes a historiographical anachronism, created mainly in the 19th century, and is not based on medieval or Ottoman documentation. Through the analysis of Ottoman archival sources, Austro-Hungarian acts and ecclesiastical documents, it is shown that the term “Serbian Church” is a modern administrative and nation-forming product, not a medieval reality.

- Introduction: the problem of historical terminology

The medieval history of the Balkans is often read through modern national categories. One of the most problematic examples of this anachronistic transfer is the use of the term “medieval Serbian church” for Orthodox cult objects built before the 19th century. This article aims to show that, in the medieval period, the Orthodox church did not have an ethnic character, but functioned within a universal religious jurisdiction, where modern national identity was unknown.

- The Orthodox Church in the Middle Ages: Jurisdiction, Not Ethnicity

In the Middle Ages, the structuring of the Orthodox Church in the Balkans was based on diocese and metropolis, canonical dependence on the Patriarchate of Constantinople and local tribal or dynastic patronage.

No medieval document uses the term “Serbian church” as an ethnic category, does not link the ownership of the church to a nation in the modern sense. Even the churches built by the Nemanjic (Nemanja) dynasties were Orthodox churches of a ruler, not “Serbian national churches”.

- Ottoman evidence: the absolute absence of “Serbian churches”

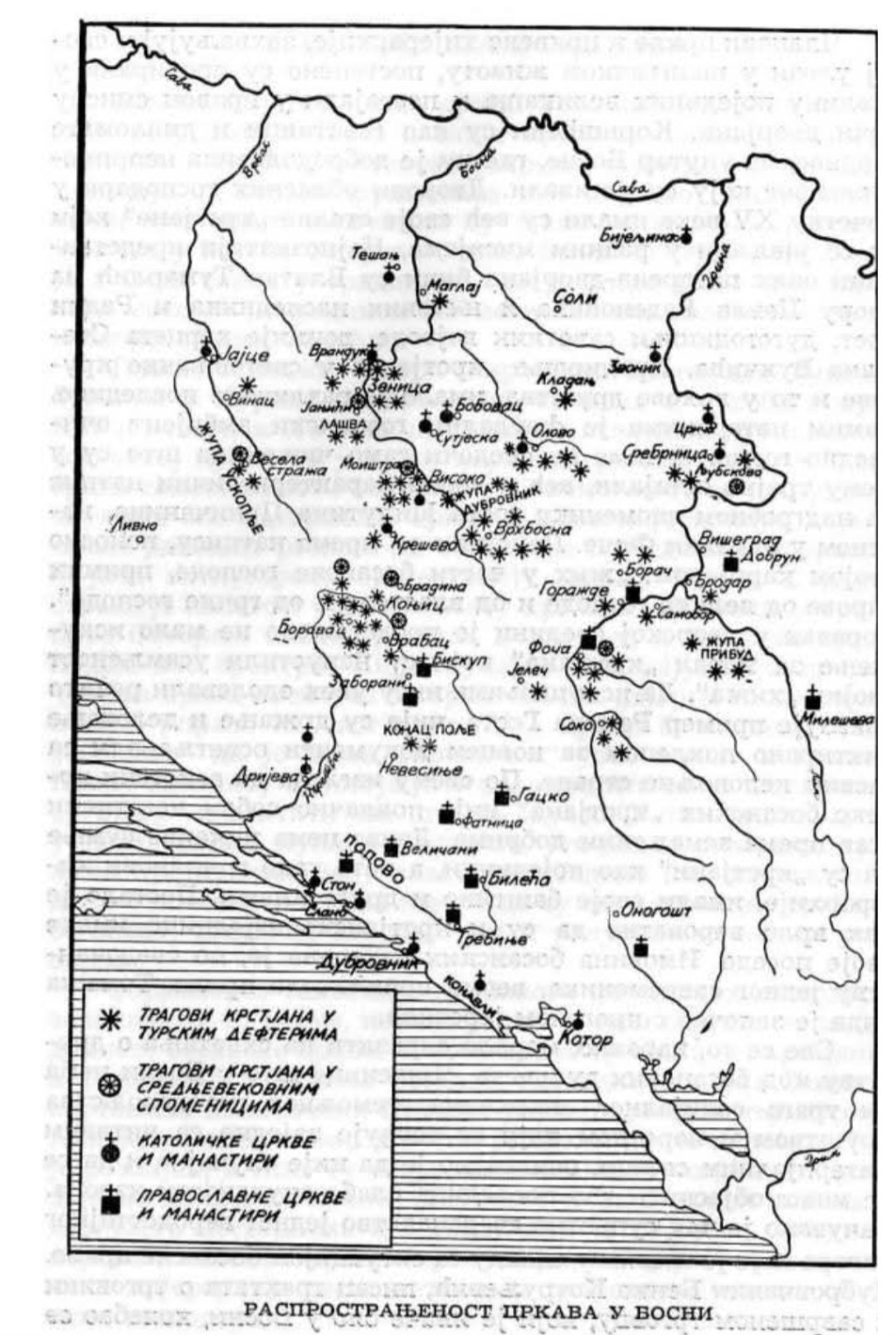

After the Ottoman conquest (15th century), administrative documentation provides a clear and verifiable picture. In the Ottoman defteri: the term “Serbian” does not exist as an ecclesiastical category. Churches are recorded as churches (churches), monasteries and Christian objects.

Sources: Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi (BOA), Tahrir Defteri Bosna, TD 146 and Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi (BOA), Tahrir Defteri Hersek, TD 174

In these documents, ethnic identity is irrelevant for the Ottoman administration, which excludes any alleged Serbian institutional continuity.

- The Patriarchate of Peja: Religious Jurisdiction, Not Ethnic

Even when the Patriarchate of Peja regained autonomy (1557), it functioned as a religious authority for the Orthodox, without ethnic divisions.

In its registers religious terminology is used, not national. The term “Serb” appears sporadically and without a modern ethnic meaning, often as a geographical or political reference.

- The decisive intervention of the 19th century

5.1. Austria-Hungary and the institutionalization of the name “Serb”

After 1878, Austria-Hungary: took over the administration of Bosnia and Herzegovina, established the need for ethnic categorization.

In this context all Orthodox churches were registered as “Serbian”. This action does not reflect the medieval reality, but creates a new legal and identity reality.

Sources: Österreichisches Staatsarchiv (ÖStA), Bosnien-Herzegowina Verwaltungsakten, Volkszählung Bosnien 1885, 1895, 1910.

5.2. Historical retro-projection

After institutionalization: the term “Serbian church” is projected back to the Middle Ages, medieval Orthodox churches are renamed Serbian, the illusion of uninterrupted continuity is created. This process represents a terminological manipulation, not a historical fact.

- Arbers, Thracians and local communities as real builders

Ethnohistorical studies and Western sources show that many Orthodox churches were built by Orthodox Arbers, Thracians of various tribes and local Slavic communities without Serbian identity. These communities were later Serbized, but were not Serbs at the time of the construction of the churches.

- European methodological comparison

The claim for “medieval Serbian churches” is analogous to calling Byzantine churches in Greece “Greek”, calling Romanesque churches in France “French”. In critical historiography, these are considered methodological errors.

- Conclusion

From the analysis of the sources it is clear that: There were no “Serbian churches” in the Middle Ages as an ethnic category; The churches were Orthodox, not national; The term “Serbian church” is a product of the 19th century; The claim of medieval continuity is a historiographical anachronism.

The myth of “medieval Serbian churches” is a modern national construction, unsupported by medieval or Ottoman sources, and should be reconsidered in the light of archival documentation.

Bibliography

Tacitus, Germania

Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi (BOA), Tahrir Defteri Bosna, TD 146 and Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi (BOA), Tahrir Defteri Hersek, TD 174

Österreichisches Staatsarchiv (ÖStA), BHV

John Fine, The Late Medieval Balkans

Noel Malcolm, Bosnia: A Short History

Nathalie Clayer, Aux origines du nationalisme albanais