by Nehat Hyseni. Translation Petrit Latifi

Abstract

This article examines the Serbian colonization and Serbization of Vranje and its surrounding areas, historically inhabited by Albanians until the late 19th century. Using Ottoman documents, oral tradition, and Serbian sources, particularly the works of Jovan Hadživasiljević, it traces the gradual assimilation of Christian and Muslim Albanians through forced conversion, surname changes, language suppression, and state colonization. Vranje’s Albanian heritage was systematically erased, while neighboring regions, such as Preševo and Bujanovac, became refuges for displaced Albanians. The study highlights the interplay of expulsion, assimilation, and survival, revealing a nuanced historical narrative of Albanian identity in South Serbia.

This article discusses the Serbian state colonization and serbization of Vranje and its surroundings, inhabited by the Albanian until the end of the 19th century.

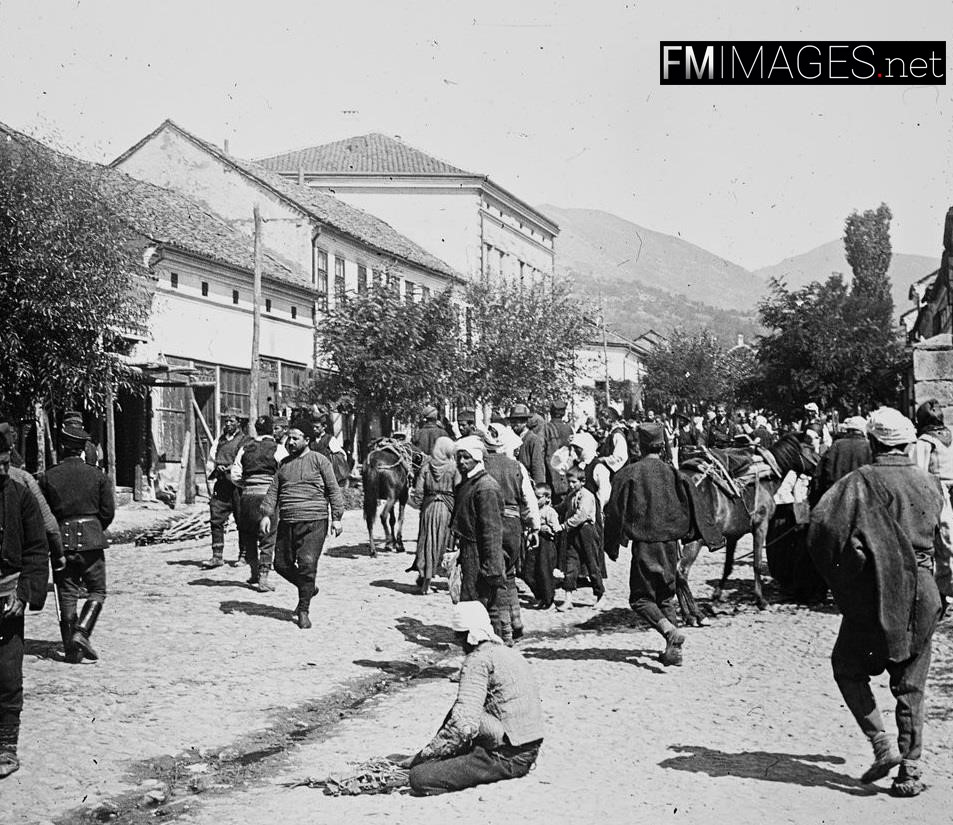

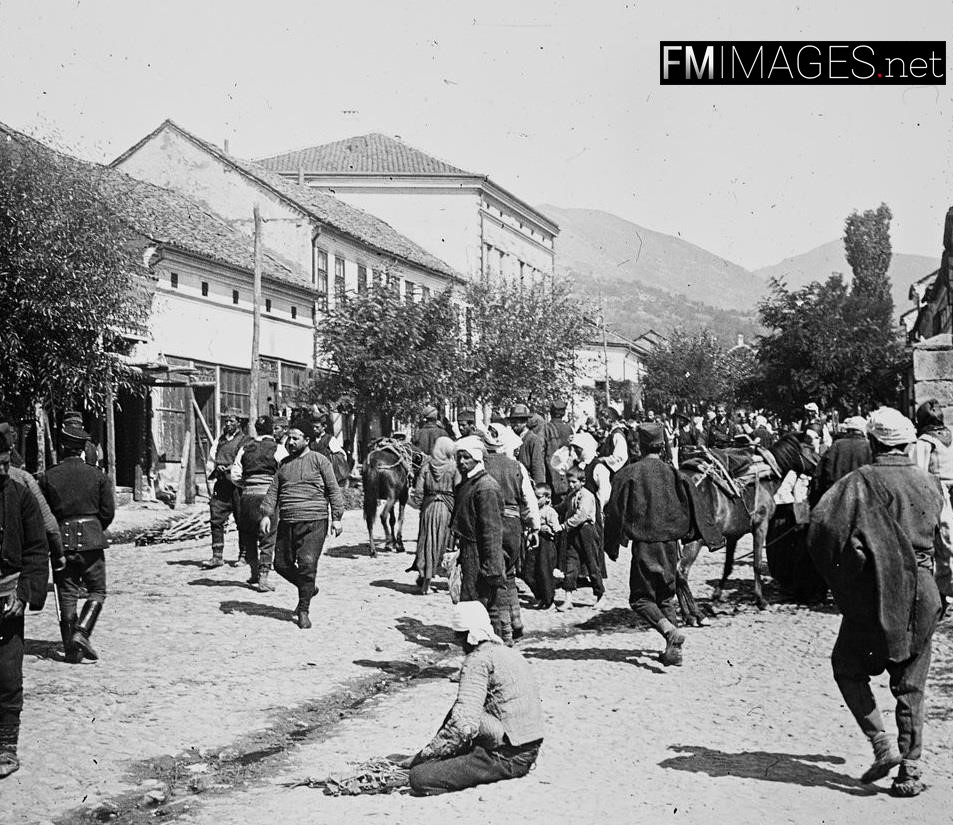

Vranje and its villages until the end of the 19th century and in the 20th century film were an area with a strong ethnic Albanian presence – Muslims, Christians and gradually serbized Christian Albanians, known in the people and in literature by the term “Arnautashe”.

Ottoman documents, oral tradition and Serbian writings themselves prove that a large part of the urban neighborhoods of Vranje, as well as the surrounding villages, were inhabited by autochthonous Albanians.

Haxhivasiljeviqi as an “unintentional” witness of Albanianness

The Serbian scientist from Vranje, Jovan Haxhivasiljeviqi, is presented, often without intending to, as a valuable witness of Albanian reality.

Although an author with a Serbian nationalist worldview and part of the ideological apparatus of colonization, he has left valuable evidence on the Albanian presence, especially of Christian Albanians in Serbia.

He identifies hundreds of urban and rural families in Vranje and the surrounding area of Albanian origin, who had once been Muslim or Christian Albanians, but who later became Serbized, changing their religion, surnames, language and ethnic identity.

He often writes that many families “are of Albanian origin, but today they are Serbs”, testifying to the completion or continuation of the assimilation process. In his works he provides family names, urban neighborhoods, areas of origin and data on “former Albanianness”.

Haxhivasiljeviqi mentions:

Muslim Albanian families expelled after 1878,

Albanian families forced to become Christians,

Families that preserved their language but lost their national identity,

Families now completely Serbized, but with documented Albanian origin.

Processes of expulsion, violence and assimilation

Vranje was a historical Albanian space where various state, administrative and police mechanisms were used to eradicate Albanian national identity and to carry out ethnic cleansing, especially during the Serbo-Ottoman Wars (1876–1878). After the wars, tens of thousands of Albanians were expelled, their properties were confiscated and the city of Vranje lost its Albanian-Muslim core. After the Congress of Berlin (1878), organized state pressure began:

prohibition of the Albanian language,

use of the church as a cultural and identity instrument,

change of surnames (adding –ić),

forced registration of Albanians as “Serbs”.

State colonization was brutally implemented by settling Serbian settlers in the abandoned houses and properties of expelled Albanians, special laws were adopted for lands, repressive agrarian reform was implemented, etc.

Meanwhile, the police and courts used cultural, psychological and physical pressure, creating social incentives for “integration into the Serbian nation” and for hiding Albanian origin for fear of punishment.

The result was the disappearance of the identity of a city, once heavily populated by Albanians.

Vranje from an Albanian space to a city “without Albanians”

At the end of the 20th century, Vranje, once an area with a strong Albanian stratification, is presented as a “Serbian, without Albanians” city. But the Albanian roots are there:

the old toponymy exists,

the internal family memory lives on,

the historical documents are undeniable.

These data destroy the Serbian thesis that “Serbs were assimilated into Albanians” during the Ottomans; on the contrary, they prove that Christian and Muslim Albanians were assimilated into Serbs, through a state-directed process. The extraordinary importance of Jovan Hadživasiljević’s work, especially “Južna stara Srbija – istorijska, etnografska i politička istraživanja” (1909, 1913), are the main sources for the study of the population of Vranje in the period of transition from Ottoman to Serbian rule.

Although nationally inclined, he documented what Serbian politics aimed to hide: a large part of the current Serbian population in Vranje was once Albanian.

Preshevo – Bujanovac – Vranje-Toplice: an indivisible Albanian historical space

If Vranje is seen together with Preshevo, Bujanovac and Toplice, the narrative becomes complete. Before 1877–1878 this was a single Albanian space, with Albanian villages, Albanian neighborhoods and neighbourhoods, Albanian toponyms, a Muslim and Orthodox population of Albanian origin and with unbroken family and tribal ties.

However, after the wars, Toplica was emptied and colonized, Vranje was Serbized and assimilated, and Preševo and Bujanovac became a refuge for the expelled Albanians and the keepers of Albanian continuity in South Moravia.

The Albanians of Preševo and Bujanovac today are largely descendants of the Albanians of Vranje and Toplica. This represents the case of the survival of the Albanian national identity through territorial concentration.

Conclusion

The history of this space is not the history of three separate regions, but of a single Albanian trunk with three destinies:

- ethnic cleansing through mass deportation (Toplica),

- assimilation and complete serbization (Vranja)

- preservation and inheritance of national identity (Preševo, Bujanovac and Medvedja)

This historical context makes Vranje a special case study in the history of Albanians in South Serbia and testifies to a hidden, but undeniable historical reality, which still preserves its deep historical memory.

Preševo, January 7, 2026