by Agron Dalipaj. Translation Petrit Latifi

Summary

This article questions the methodological foundations of comparative linguistics as a discipline that claims authority over etymology. It argues that comparative linguistics does not investigate the internal formation of words but instead reconstructs lexical history through written documentation, language contact, and formal resemblance. By equating earliest attestation with origin, it substitutes documentation for explanation and elevates this substitution to dogma. The paper contends that genuine etymology must explain the internal motivation of words through structural and semantic decomposition. Using the case of Albanian, the author argues that the dominance of comparative linguistics has resulted in ideological distortions, excessive loanword classifications, and the marginalization of alternative research, ultimately producing a pseudoscientific model of etymology divorced from meaning and cognition.

In official discourse, we are told that etymology is a precise, closed, and accomplished branch of knowledge

We are told that words “have received their stamp,” that their origin is determined, and that any further discussion is futile, even unscientific. But if we stop and simply ask: what does comparative linguistics really do when it says it does etymology, the picture changes radically.

Comparative linguistics never enters the word. It takes the word as an initial unit, indivisible in meaning, as a “ready-made object.” It does not ask how the word was created, why it has this form, why this sound is associated with this meaning. It does something else: it searches for the earliest written documentation and connects the word with another language through formal similarity or through the history of contacts.

But early documentation is not the creation of the word. Writing is a very late stage in the history of language. Words existed, functioned, and were understood thousands of years before they were fixed on parchment or paper. Then the fundamental question arises:

Why is the first written address of a word called “etymology”?

The word etymology itself belies this claim. The Greek etymós comes from the verb ετόίμαζω, which means to prepare, make ready, prepare, while lógos means “word, explanation, cause, reason”. So etymology is the explanation of the true meaning of a word, not its administrative registration in a given language. There is nothing “true” about the internal meaning of a word just because it appears for the first time in a Turkish, Greek, or Latin text.

Comparative linguistics, in effect, has replaced the question “how did the word originate?” with the question “where was it documented earlier?” This is a methodological substitution, not a scientific necessity. And then this substitution has been elevated to dogma. Any attempt to enter the word, to decompose it into its most minimal units of meaning, to search for its natural motivation, is immediately declared “folkloristic”, “romantic”, “amateur”, “unscientific” or “intuitive” and even “charlatanism”.

But what kind of science is that which refuses to explain its object? What kind of etymology is that which does not explain why a word is exactly what it is?

The truth is this:

Comparative linguistics does not do etymology in the full sense of the word.

It does lexical history, genealogy of documents, cartography of borrowings.

These are useful works, but they are not etymologies. Etymology begins where the word is decomposed, where meaning arises from structure, where form and semantics are necessarily connected. The claim that only comparative linguistics does etymology is, in essence, a terminological monopoly.

And any monopoly, when not challenged, turns into dogma. The time has come for this monopoly to be questioned, not to deny the value of comparison, but to return to etymology its true meaning: the discovery of the internal reason of the word.

“Etymology” according to comparative linguistics for the Albanian language has been applied in the most abusive way possible. As long as this linguistics never manages to enter inside the word and decompose it into more minimal meanings, to claim the way in which the word was created and in which language the minimal meanings coincide, this linguistics cannot claim to know the origin of words and should not allow itself to declare a word as a loanword or a country word.

Thus, the Albanian language, after the latest dictionary with 13 thousand loanwords by academician Bardh Rugova “Turkisms in the Albanian Language”, officially Albanian remains with 2% of its own words and 98% loanwords. This report is completely false and comes from the ideologically directed use of a pseudoscience, known as official etymology.

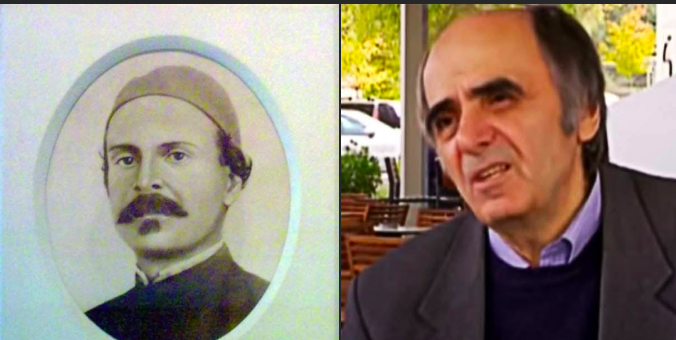

The fact that officially “no” old written documents for Albanian are found, comes as a result of the fact that the official Albanianology of Tirana has never invested in finding Albanian writings of antiquity and even when they are found, as is the case when Nikos Stylos finds Albanian writings from the 2nd – 10th centuries BC, they are not taken into consideration and even an official hostile attitude is maintained towards this author who has devoted his life to giving the Albanian nation its hidden and stolen cultural identity.

In conclusion, I say that: a word is not born in an archive. It is born in the mind, in experience and in meaning and the exclusion of these circumstances has brought to the surface a pseudoscience, such as comparative linguistics, to be used wildly against the Albanian language.