Author: Sadri Bajraktari. Translation Petrit Latifi

Summary

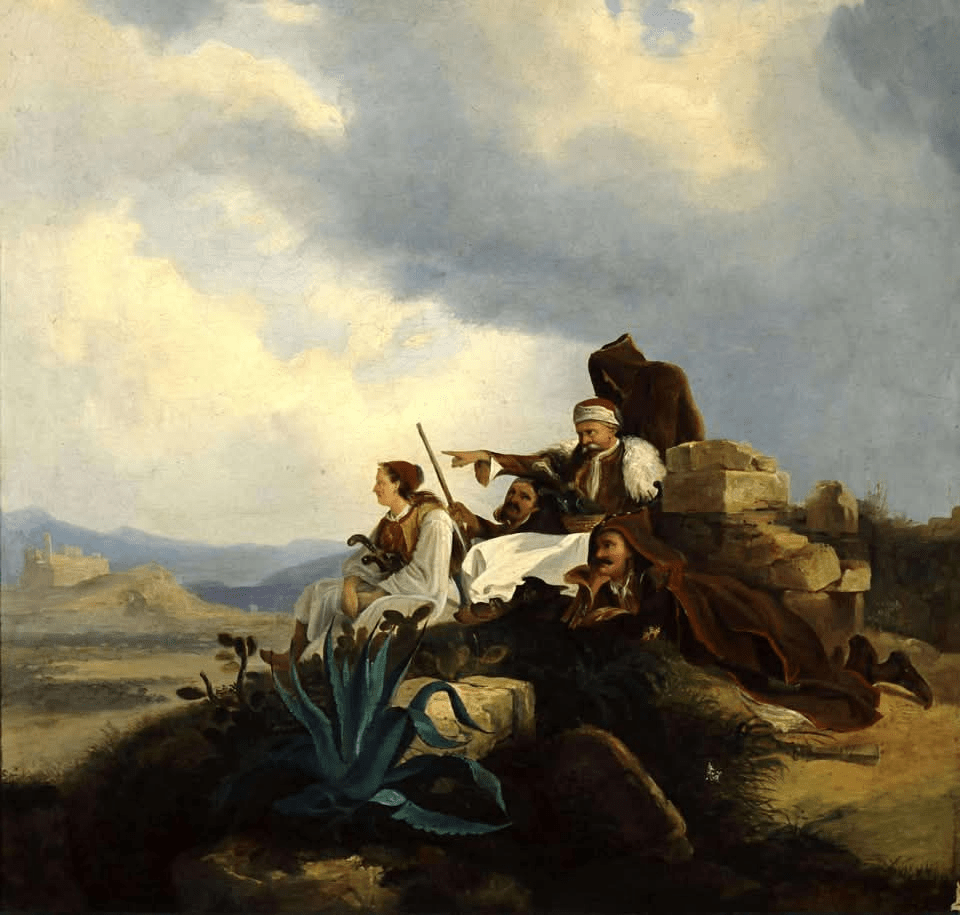

After Greece gained independence, the issue of choosing a national language became a crucial political and cultural question. Although Arvanites (Albanian-speaking Greeks) made up a large portion of the population and many members of parliament, Greek was ultimately chosen as the official language in 1829. This decision is controversial because Arvanite leaders such as Marko Boçari and Theodoros Kolokotronis had played a central role in the 1821 War of Independence.

At the time, Arvanitika (an Albanian dialect) was widely spoken in many regions, often more commonly than Greek, even in churches. Arvanites were known for their strong cultural values, especially besa (honor and keeping one’s word), and for their bravery in battle. Despite this, the new Greek state adopted Greek for administration, education, and public life, which gradually marginalized the Albanian language and Arvanite identity.

Antonio Bellusci documents testimonies showing how deeply rooted Arvanitika was in daily life, law, religion, and community values. He argues that the responsibility for the loss of the Albanian language in Greece also lies with the Arvanites themselves, who accepted Greek as the official language. Many Albanian-speaking heroes contributed to the creation of the Greek state, yet their Albanian identity has often been downplayed or forgotten.

Despite this, ordinary people continued to celebrate their Arvanite heritage through songs and traditions, political decisions had already shifted Greece toward a Greek-only national identity, leaving Arvanite culture increasingly marginalized.

The Choice of 1829

In 1829 the Greek Parliament faced a historic decision regarding the national language of the newly liberated state. Despite the fact that over 80% of the parliament members were Arvanites who spoke Albanian as their native tongue they ultimately voted to make Greek the official language. This decision remains a point of deep historical discussion because Arvanite leaders and heroes like Marko Boçari and Theodoros Kolokotronis were the primary force behind the 1821 Revolution.

At the time Arvanitika was the dominant language in many regions where Greek was barely understood even in religious services. The Arvanites were renowned for their cultural values such as Besa and their bravery on the battlefield. However the transition to a Greek-only administration began a process of marginalization for the Albanian language in Greece. While the people sang of their language as a tongue of bravery the political elite chose Greek to align the new state with ancient heritage and international diplomacy.

Antonio Bellusci writes:

“During those years, the Arvanite language was widely spoken in Greece, and this is confirmed by the recording that I made of the lawyer Lljapis: “I am an Arvanite lawyer and I have had work for 10 Greek lawyers. The Arvanites come to me because I know the language. I like the word ‘besa’. I am a lawyer, but I am also an Arvanite. The Arvanite makes the besa, so I keep my word. I protect them. The Arvanite does not speak in vain, but before he utters the word, he thinks it over, then he says it and not only that, but he tries at all costs to keep his word.”¹⁷

“In the house of George Priftis Papanastasis, while I am recording, I ask him:

– When you sang in Albanian in church, your heart…

Before I could finish my sentence, he answers me:

– Our hearts would jump. Here, even the priest sang Albanian. Nobody spoke Greek. The Greek language was not known.¹⁸”

And yet, the Albanian language was not made official, but only the Greek language. I think and agree with the opinion of my Arvanite brother, Aristidh Kollja, when he says that the problem and responsibility fall on the Arvanites themselves, because the Arvanites were given the opportunity to choose which language to speak, Greek or Albanian.

History proves that many Albanian heroes of Greece fell in the war and many fought for the liberation of Greece.

Some of the Arberians of Greece, heroes of the 1821 revolution, were: Gjeorgjio Kundurioti, Kiço Xhavëlla, Andoni Kryeziu, Teodor (Bythgura) Kollokotroni, Marko Boçari, Noti Boçari, Kiço Boçari, Laskarina Bubulina, Anastas Gjirokastriti, Dhimitir Vulgari, Kostandin Kanari, Gjeorgjio (Llalla) Karaiskaqi, Odise Andruço, Andrea Miauli, Teodor Griva, Dhimitir Plaputa, Nikolao Kryezoti, Athanasio Shkurtanioti, Hasan Bellusci, Tahir Abazi, Ago Myhyrdari, Sulejman Meto, Gjeko Bei, Myrto Çali, Ago Vasiari and many, many other Albanians.

From these Arbërorëts came many of the heroes of 1821 and the creators of the new Greek state. This truth, especially in recent years, has been hidden from the Greek people for many reasons. The name “Arvanitas” in Greece should have been an honorary title and not ended up as an almost offensive term.

As an Arbëresh, I wonder how the Arvanites, leaders from land and sea, managed to choose Greek when in 1829, the issue of which language would be chosen as the official language, between Albanian and Greek, was raised in parliament, when the parliament was composed of over 80% Arvanites.¹⁸

In the offices of Greece, from that moment on, only Greek would be written and spoken. Where was that Albanian, Arvanite pride in those moments, when ordinary people sang:

“This Arbërish gloom,

It was the valiant gloom

Of Navarko Miaulli,

Boçari and all of Suli.”

Verses that resemble a protest, a hymn, a call, but it was too late.¹⁹”

References

¹⁷ You will find this testimony on page 135, Ricerche e studi tra gli arbërori dell’Ellade.

¹⁸ In the book Da radici arbëreshi in Italia a matrici arbërore in Grecia, page 362, “Angellokastros”.

¹⁹ Link, article “Dossier albanesi di Grecia”, page 207.

Note: I recorded the above verses in 1969, from an Arvanite named Pavlos Giannakopoulos, 65 years old, born in Sofikò (Corinth), with an engineer’s profession, who approached me himself and began to recite them proudly.

Source

“The Journey of an Arbëreshi. Life, works, memories”. Author: Antonio Bellusci. Interviewer and reviewer: Ornela Radovicka. Editor: Elona Qose. Publisher: Tirana, Maluka