Collection by and translated, edited and processed by Petrit Latifi.

Astract

This article is a curated anthology of scholarly studies relating to the Proto‑Albanian language and alphabet, compiled and translated by Petrit Latifi for Balkan Academia. It brings together a series of historical, onomastic, linguistic, mythological, and etymological texts from researchers and contributors across various fields. The works range from analyses of ancient bas‑reliefs and early Albanian manuscripts to studies of medieval texts, inscriptions predating classical Albanian documentation, and evidence of diverse Albanian writing traditions (Greek, Latin, Cyrillic scripts). Together, these contributions aim to broaden understanding of early Albanian linguistic heritage and historical documentation.

Credit to authors:

Fahri Xharra, Albert Nikollay, Alexander Hasanas, Eli Eli, Sofronio Gassisi, Enrico Galbiati, Ornela Radovicka, Agron Dalipaj, Nikos Stilos (Stylos), Niko Kortheja, Vullnet Xhango, Sazan Guri, Muharrem Abazaj, Lulzim Osmanaj, Kol Marku, Arben Llalla, Avni Rrustem Mahmutaj, Luljeta Rakipi.

Alexander Hasanas:

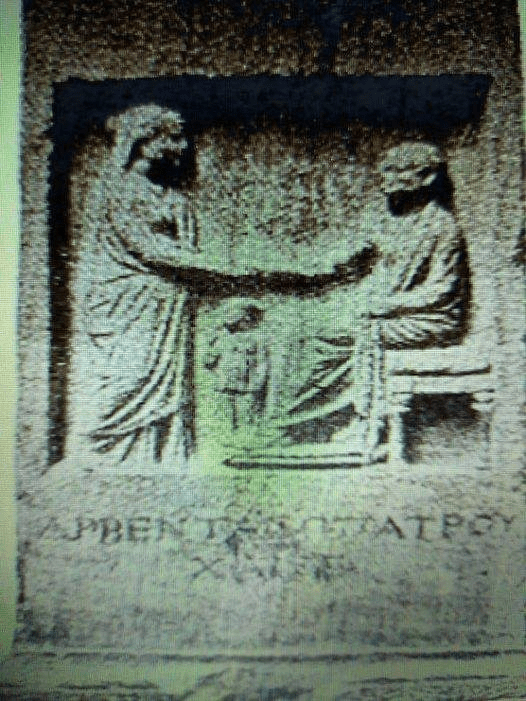

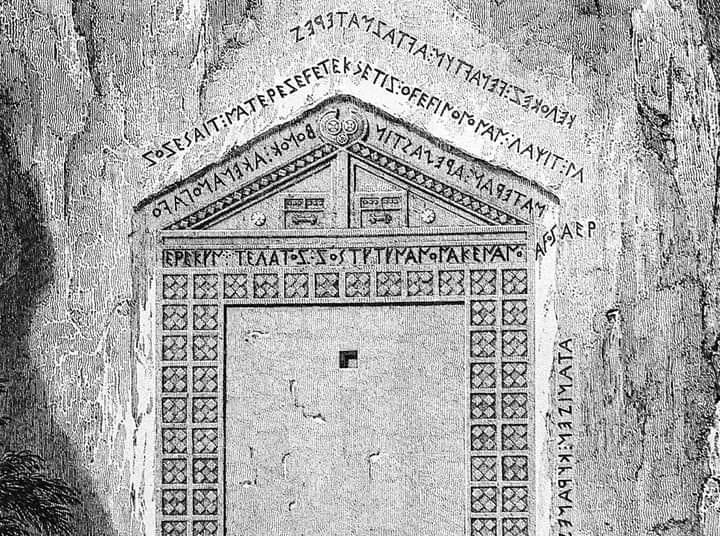

Basorelief written in Albanian (Arberian or Troyan)

In this ancient bas-relief, the name Arben is clearly read and unfortunately the rest of the text is illegible. From this text (subtitles) we understand that:

1 – The Arben people (or the proper name Arben) are much older than is suspected.

2 – The events of Troy are historically linked to the Albanians (as a people or as individuals).

3 – The alphabet that from the 19th century onwards is called exclusively “Greek”, is not at all like that, but has been used by Albanian speakers since the beginning of time, I add that I am sure that that alphabet was made by Albanians.

Photo and text borrowed from our late Arvanite friend Kotsios Kotskas.

Eli Eli writes:

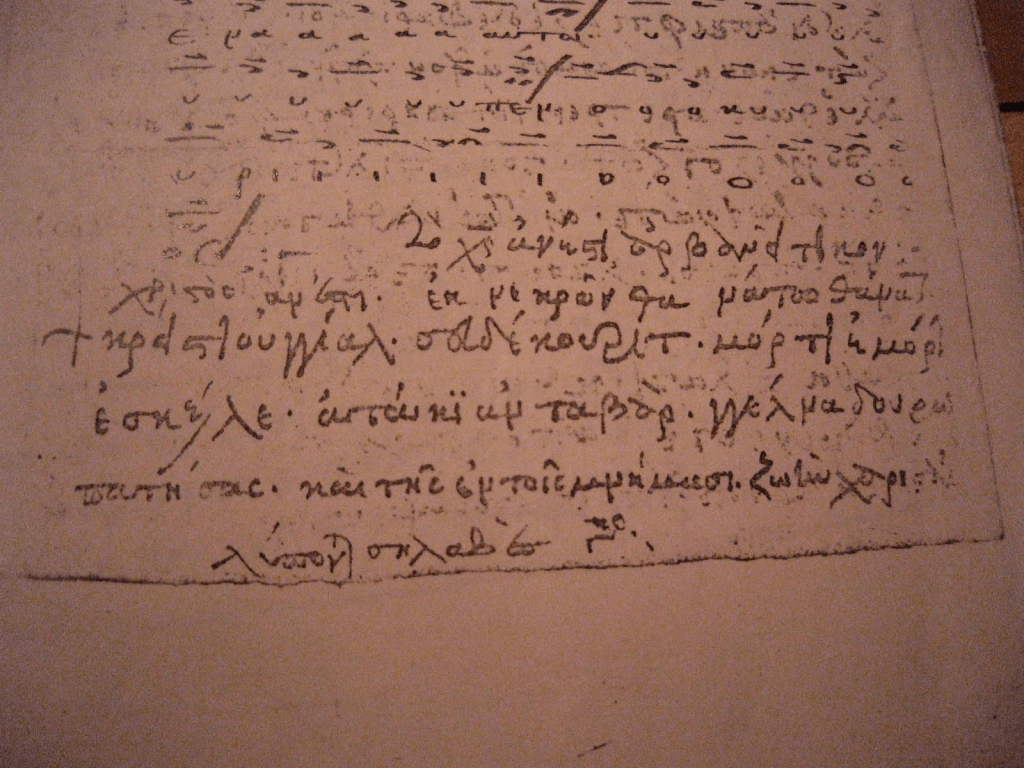

The Easter Gospel, the Resurrection Hymn, the Sins of Friday.

The Easter Gospel documents as early as the Mass of John Buzuku, rarely if ever spoken of. I am among the Arberesh of Kuntiza in Sicily, and I am in the company of Avv and scholars of the Arberesh world, of the Byzantine rite in particular Prof. Kalogero Raviotta:

“We often talk about the Missal of John Buzuku but why is there no mention of an even earlier book in the Albanian language, although written in Greek letters; the “Easter Gospel” There are fifteen lines translated from the Gospel of Saint Matthew (27: 62-66).

This discovery was made by the Greek historian Spiridon Lampros (1851-1919) in 1906, within a manuscript Written in Greek which was kept in the Ambrosian Library of Milan.

The Albanian text was inserted into a Greek codex, as specified in the report of Father Marco Petta, hieromonk of the Greek Abbey of Grottaferrata, “Published and unpublished works of Father Sofronio Gassisi” but, “Father Sofronio Gassisi should be given the credit for having reported the oldest well-known text in the Albanian language, the “Maketë të Premten”, known to this day, XXVII. 62 et seq.) data from the Ambrosian codex gr 133, 14th century (A. Martini D. Bassi, Catalogus Codicum Graecorum Bibliotecae. T. I, p. 147.)

This work is a certain exception from the Orthodox tradition; firstly, because the work belongs to two hundred years earlier than other important Albanian texts in the Greek alphabet and, secondly, because it was found in northern Italy.

It was on this happy occasion that Father Sofronio began to correspond with the then prefect of the Ambrosian Library, Ms. Achille Ratti (later Pope PIUS XI), who, in addition to informing him more precisely about the bibliographical data, sent him a photographic reproduction of the indicated page”.

Monsignor Enrico Galbiati, prefect of the Ambrosian Library, in a handwritten note, specifies that on folio 63 recto and vice versa the hymn of the Resurrection is reported first in Greek (Cristòs anèsti….) and then in Albanian (Cristi u gjall…..) and attached a photocopy of the same leaf.

However, all scholars agree to accept that the two texts cited are the oldest written Albanian documents: the baptismal formula in so-called Latin letters and in the Gheg dialect (Northern Albania), the Hymn of the Resurrection in so-called Greek letters in the Tuscan dialect (Southern Albania). (Bibliogrfia Codex 133, p. 63. cr. Martini-Bassi Catalogus Codicum Graecorum, as well as Lampros 1906, Borgia 1930.)

Taken from the Cycle

Me and the Arbëresh.

Ornela Radovicka

Albanological Center on the Arbëresh Language and Culture

Founded by Father Bellusci.

Agron Dalipaj writes:

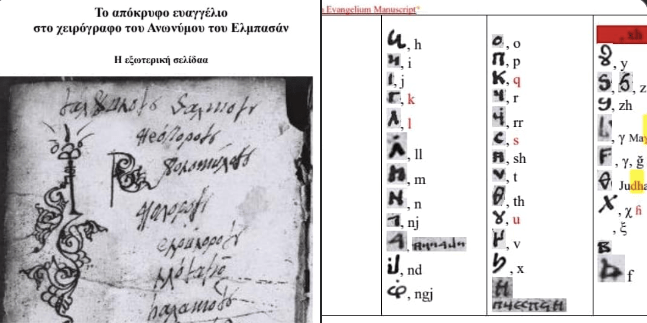

A great discovery in albanian historiography. The anonymous Elbasani Manuscript is the Gospel according to Saint Andrew, which until today was assumed to be lost and had no copies anywhere in the world. This is confirmed by the albanologist and etruscologist Nikos Stilos, who will soon present it transliterated into modern Albanian and in Greek.

The gospel is written in the elbasan alphabet with 43 graphemes. this text, which is kept in the albanian state archives, has been examined by many scholars, but none of them understood the treasure it contained, both for world christianity and for the history of albanian writing.

Stilo confirms that the text belongs to the Christian sect of Bogomils that spread most widely in Bulgaria and Albania and had its splendor in the years 1200 – 1300 and it is thought that this gospel text belongs to that period.

This case also proves the intellectual sterility of the academics of Tirana who have the text and cannot read or understand it. Or they did not want to tell what it is about because they cannot overcome the Slavic milestones that Albanian writing begins with Buzuku in 1555. According to Andreu, the Gospel has survived thanks to the ignorance of Albanian academics to understand what it was and their inability to transliterate it. Perhaps today it would be in Belgrade.

An Albanology freed from Slavic control would have many other achievements like this. We note that the genius of Etruscan and Albanological studies Nikos Stilos is the author of about 20 important publications in Albanology and has also found other Albanian texts before Christ. Stilo’s work is in itself an indictment of the pseudo-Albanology of Tirana, which has maintained a nihilistic attitude towards his work. Stilos is the De Rada of our time and of the same greatness of Petro Zheji.

The Gospel according to Andreu will be promoted first in the university network of Germany. I take this opportunity to thank the discoverer of this gospel, the enlightened Nikos Stilo, who was kind enough to send me the entire gospel and with his permission and trust, I am giving you the first 14 pages with photographs

We hope that the Tirana University of Technology will welcome this important discovery and not bring out the scumbags and the memush to underestimate this historical discovery in Albanology that comes from someone who has ignored it forever.

Let’s enjoy this discovery and share it with everyone.

Niko Kortheja writes:

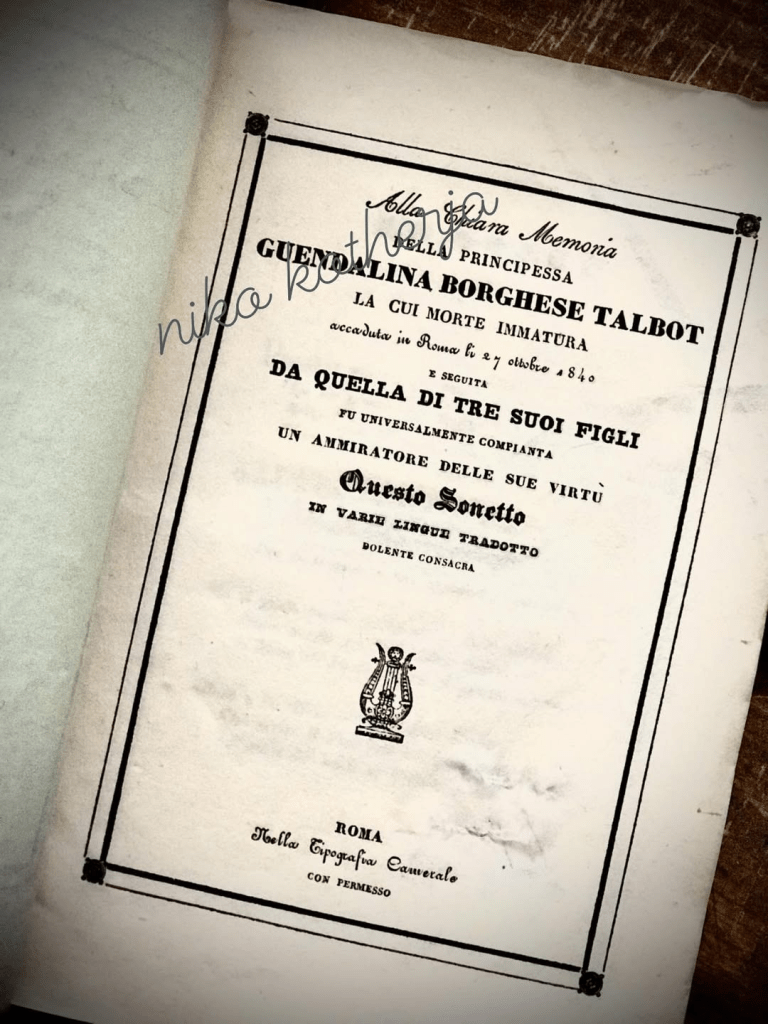

A rare edition with Albanian text, published in Rome in 1840.

The 16-page volume contains a sonnet dedicated to the memory of Princess Guendalina Borghese Talbot, written by the “admirer of her virtues” Francesco Fiorini. The sonnet comes in its original Italian version and is further followed by translations in Latin, Greek, English, Irish, French, Spanish, German, Danish, Polish, Albanian, Hebrew, Syriac, Arabic, Egyptian.

Brought into Albanian and Greek, the versions bear the signature of Dr. Pietro Matranga (1807-1855), born in Piana degli Albanesi and educated at the Arberesh Seminary of Palermo. The erudite was appointed secretary of the Vatican Library and rector of the College of Saint Athanasius in Rome.

This Albanian manuscript by Matrange, published in 1840 in this volume, consists of the only writings of his in Albanian that have survived to this day and remains one of the rare documents in the chronology of the writing of our language, having come to light more than 180 years ago.

Vullnet Xhango writes:

A Voskopojar Interpretation of Early Doric Inscriptions

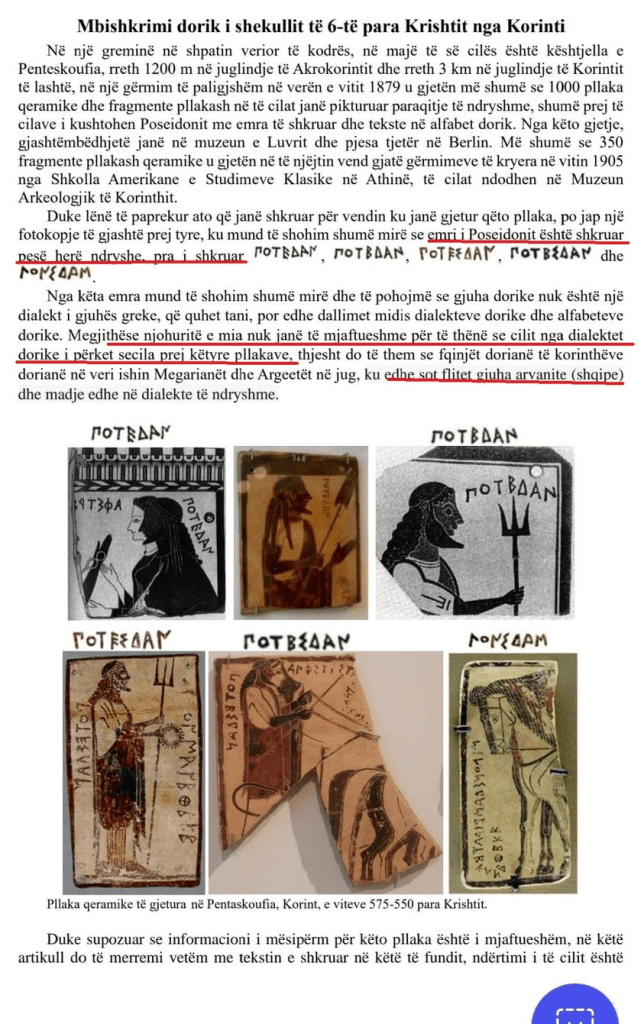

The phrase Të Dhan(ë) was written in Albanian in the 6th century BCE as 𐊓OTE𐊣A𐌍. In his article “Doric Inscription of the 6th Century BCE from Corinth”, published on Agron Dalipaj’s website, Niko Stylos presents several artifacts, including numerous ceramic plates unearthed in the region. From these, he selected a subset for interpretive analysis. Short inscriptions are found on the surfaces of the plates. Stylos has reproduced the inscriptions at the top of the images, which provides a useful reference, although his readings are open to scholarly debate. He argues that the six plates presented on the first page reference the name of Poseidon, noting that the name appears in “five different forms.” The author accompanies his study with a detailed table mapping the inscription elements to corresponding letters in the Albanian language, demonstrating a high degree of professional rigor.

I consider Voskopojar’s work to be essential for understanding early writings across millennia. He attempts to summarize and connect figurines and letters over a temporal span of approximately 4,000 years, a generalization that is not fully realizable within the constraints of contemporary scholarship. Consequently, in my table “Letters of the Inscription Alphabet”, I indicate the letters as used by Voskopojar according to my own assessment. Based on this, I offer an interpretation of five inscriptions, demonstrating the methodology and practice of transcription according to the principles of epigraphic science. This methodology was extensively discussed in my previous work, Letters, Images of Pelasgian Figurines.

The inscriptions, their transcriptions, and interpretations are as follows:

- 𐊓OTE𐊣A𐌍 → transcribed as PO TE DHAN (“Yes, to give it”)

- 𐊬OTᛒ𐊣AN → transcribed as PO T KS DHAN (“Yes, to not (KS) give it”)

- 𐊓OTEᛊ𐊣A𐌍 → transcribed as PO TE ND DHAN (“Yes, to stop giving it”)

- 𐊓OTᛒᛊ𐊣A𐌍 → transcribed as PO T KS ND DHAN (“Yes, to not stop giving it”)

- ᛚONᛊ𐊣Aᛖ → transcribed as PO N ND DHAM (“Yes, to share it”)

In these transcriptions, the letter 𐊣 is rendered as Dh, the figure ᛒ as KS, and the figure ᛊ as ND. Consultation of Shkronjat e Elbasanit is indispensable for accurate understanding.

The inscriptions are presented in standardized Albanian:

- PO TE DHAN – “Yes, to give it”

- PO T KS DHAN – “Yes, to not give it”

- PO TE ND DHAN – “Yes, to stop giving it”

- PO T KS ND DHAN – “Yes, to not stop giving it”

- PO N ND DHAM – “Yes, to share it”

Given that all the tablets were found in the same context, they likely reflect a system of negotiation and agreement. This is illustrated through figurative depictions, such as a woman, a knight mounted (or dismounted) on a horse, in transit or returning. Based on the first two views, the images may depict a man requesting a woman or slave from an owner, with the tablets recording the responses and reactions. The first and second inscriptions express peaceful outcomes, the middle inscriptions reflect harsher responses, and the final inscription depicts a satisfied or victorious return.

This series may represent an educational methodology for teaching agreements. By collecting and analyzing nearly 1,000 similar artifacts, it is plausible to suggest that the site functioned as a locus for instruction and learning.

Lulzim Osmanaj writes:

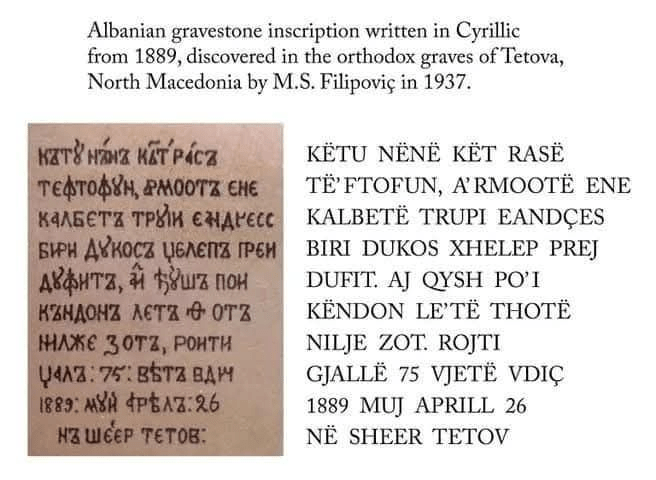

The Albanian Cyrillic inscription of Tetovo (1889): evidence of the graphic diversity of the Albanian language in the 19th century

One of the most significant pieces of evidence of the historical development of the Albanian language and script is the inscription found in an Orthodox tomb in the city of Tetovo, North Macedonia, dating from 1889.

This inscription, which was discovered by the Serbian scholar M.S. Filipović in 1937, is written in Albanian but using the Cyrillic alphabet. The discovery constitutes an important source for Albanological studies and for the history of the Albanian alphabet, testifying to the graphic plurality that characterized the Albanian script before its standardization at the beginning of the 20th century.

The text carved on the stone translates as follows:

“Here under this cold rasa rests the body of the feeling son of Dukos Xhelep from Dufi. Let him who is singing this say: God, have mercy on him. He lived 75 years. He died on April 26, 1889 in the city of Tetovo.”

This text contains clear elements of northern Gheg, which is evidenced in the use of forms such as “të ftofun”, “trupi i ndjes”, “rrojti”, or “qësh po’i ngënton”. These forms show the preservation of the phonetic and morphological features of the Albanian spoken in the northern and northeastern regions of the Albanian lands.

The dialect used in this inscription coincides with the linguistic variations documented in other Albanian manuscripts of the 19th century, before the process of unification of the alphabet was undertaken at the Congress of Manastir in 1908.

The use of the Cyrillic alphabet in this context is an element of particular cultural importance. It shows the influence of the Orthodox tradition on the Albanian communities of the Tetovo area, which, for religious and cultural reasons, had more access to the Cyrillic alphabet than to the Latin one.

According to researchers of the history of Albanian writing, before the unification of the alphabet, at least three parallel writing traditions existed: the Latin one (used mainly by Catholics in the north), the Greek one (present among the Orthodox communities in the south) and the Cyrillic one (in the mixed Orthodox areas of Macedonia and Kosovo) (Elsie, 2005; Demiraj, 2010).

This inscription, in addition to linguistic evidence, also represents a valuable source for the social history of Albanians. It mentions the profession of the deceased — “Xhelep”, which means cattle trader — and indicates a social class linked to the traditional economy of the time. The way in which the funeral prayer is formulated “He who sings this, let him say: God, have mercy on him” testifies to an Orthodox Christian religious sensitivity, while the use of Albanian as a written language in a tomb of this time establishes Albanian as a living liturgical and cultural language, despite the lack of standardization.

In terms of the development of Albanian writing, this discovery has multiple values: it proves the existence of an early writing tradition in the native language in regions of the Balkans that are often left out of the historical spotlight. Moreover, the fact that such an inscription was made in the Cyrillic alphabet, at a time when the use of Latin letters was spreading in Albania, proves that the process of cultural and linguistic identification of Albanians was still developing and the cultural influences were complex and multiple.

In conclusion, the Albanian inscription of Tetovo from 1889 represents a unique testimony of the intertwining of language, religion and cultural identity in the Albanian space. It remains a valuable artifact for historical linguistics and for the study of the spread of Albanian writing in different periods and graphic environments, testifying to the vitality of the Albanian language and its ability to survive in different forms of expression and writing.

References

Demiraj, Sh. (2010). Gjuha shqipe dhe historia e saj. Tirana: Akademi e Shkencave e Shqipërisë.

Elsie, R. (2005). Albanian Literature: A Short History. London: I.B. Tauris.

Filipović, M. S. (1937). Prilozi za etnografiju Albanaca u Makedonije. Beograd: Srpska Kraljevska Akademija.

Sazan Guri writes:

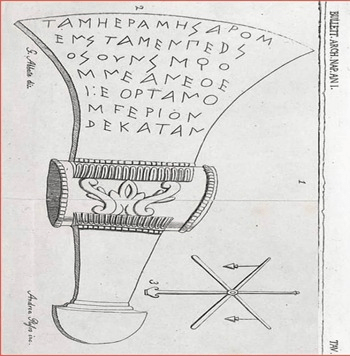

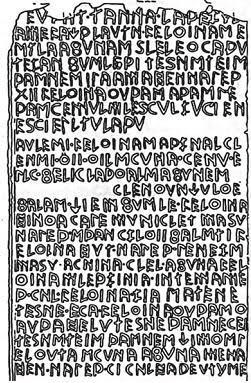

Deciphering an Etruscan Inscription: “A Family Line That Perishes (SOS)”

A group of senior scholars debated whether this Etruscan inscription conveyed any meaning in Albanian. I promised to provide a positive solution, and shortly thereafter, Professor Muharrem Abazaj in Italy successfully completed the transcription within two to three days, making it readable in contemporary Albanian. Here, we present the first and last lines of the inscription; however, the full transcription can be provided to those seeking it, accompanied by coffee, as a gesture to disseminate knowledge of Albanian cultural heritage.

Title of the Inscription: A Family Line That Perishes (SOS)

The inscription is written in an Etruscan script, using a Pelasgian/Phoenician alphabet, which was in use during the 4th century BCE and earlier.

Methodology of Decipherment

The following steps were undertaken:

- Transcription: Each line of the Pelasgian/Etruscan characters was transliterated into the corresponding letters of the Albanian alphabet.

- Segmentation: Words were identified and separated, as the original script is linear and lacks word divisions.

- Interpretation: The meaning of each word was analyzed and determined.

- Reconstruction: The overall content of the inscription was reconstructed.

Transcription and Interpretation

Line I: I TAMHERAMNSROM

Transliterated: T AM HERA M NS ROM

| Segment | Albanian Meaning | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| T AM | te ama | “to mother” |

| HERA | Hera | personal name of the mother |

| M | ma / më / akoma | “still” |

| NS | nuk | “not” |

| ROM | rrojmë | “we live” |

Interpretation of Line I:

“To Mother Hera, we no longer live.”

Line VII: NDEKATAN

Transliterated: N DEK AT AN

| Segment | Albanian Meaning | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| N | në | “in” |

| DEK | dek (Gheg) | “dead” |

| AT | ati | “father” |

| TAN | të tanë / të tërë | “all / whole” (when two identical consonants appear, only one is written) |

Interpretation of Line VII:

“With the father dead, all (is finished).”

This line symbolically represents the closure of the family line.

Content of the Inscription

The inscription narrates a tragic family event: a man has killed his wife, and the son or daughter reacts with anger toward the father. The child cannot live without the mother, and with the death of the father, the family line comes to an end. The depiction conveys both literal and symbolic meaning regarding the cessation of life within the household.

Supporting Visual Elements:

Beneath the main figure, a semicircular motif directs three arrows toward the central object, representing the family trunk. At the center of the trunk, a flower-like figure is inscribed, yet the letters SOS are clearly discernible. This emphasizes the concept that the family line has ended.

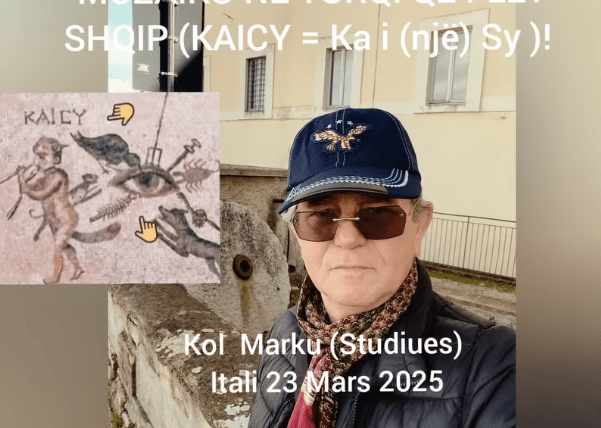

Kol Marku writes:

The Inscription “KAICY” and Evidence of an Illyrian Writing System Using the Pelasgian Alphabet: The Role of Mosaic in Reconstructing Historical Truth

Summary:

The mosaic inscription “KAICY” (ΚΑΙCΥ), discovered in present-day Turkey and preserved in the Archaeological Museum of Hatay, provides compelling evidence for the use of writing by Illyrians and Pelasgians. The inscription, depicting an eye surrounded by symbolic figures, is written in a script traditionally classified as ancient Greek but demonstrably derived from a Pelasgian alphabet. Transliteration and linguistic analysis reveal that KAICY corresponds to an Albanian expression, “Ka i sy” or “Ka një sy,” reflecting the concept of the evil eye. Classical sources, including Diodorus Siculus, Titus Livius, and Pliny the Elder, support the antiquity and indigenous origin of the script. This study argues that the mosaic confirms the continuity of the Albanian language from Illyrian and highlights the role of epigraphy in reconstructing the cultural and linguistic heritage of the ancient Balkans.

Authors: Kol Marku & IA

Introduction

Ancient mosaics are more than visual art; they serve as historical documents preserving traces of forgotten civilizations. A particularly notable mosaic, bearing the inscription “KAICY” (ΚΑΙCΥ), depicts an eye surrounded by animals and symbolic figures. This artifact, discovered in present-day Turkey, is housed in the Archaeological Museum of Hatay. While the image used here is sourced online for illustrative purposes, its authenticity has been verified by the museum.

This essay examines the mosaic within the context of Illyrian and Pelasgian literacy, drawing upon linguistic, epigraphic, and classical sources, including Diodorus Siculus, Titus Livius, Pliny the Elder, and others. The objective is to explore the cultural and linguistic significance of the inscription, providing evidence for the continuity of the Albanian language from its Illyrian/Pelasgian substratum.

1. Analysis of the Inscription: “KAICY”

The mosaic’s inscription is written with letters traditionally classified as part of the “ancient Greek” alphabet, but which originate from a Pelasgian source:

- Κ = K

- Α = A

- Ι = I

- C = S (early Arcadico/Doric sigma)

- Υ = Y (upsilon)

The transliteration reads KAISY, which, in a dialectal Albanian pronunciation, is rendered as “Ka i sy” or “Ka një sy” (“There is an eye” or “It has an eye”). This expression conveys the concept of the “evil eye,” a superstition still present in Albanian culture. The symbolism of the eye parallels certain interpretations of Egyptian pharaonic names, such as Ramses II, interpreted as “Ra më Sy” in folk etymology; however, in the case of the mosaic, the expression is clearly Albanian and unrelated to other languages.

This interpretation is invisible in ancient Greek or Latin but makes direct sense in modern Albanian, strongly supporting the hypothesis of linguistic continuity from the Illyrian/Pelasgian substratum. It also implies that writing was employed for a pre-Greek language.

2. Did the Illyrians and Pelasgians Have a Writing System?

Contrary to claims that the Illyrians lacked writing and borrowed it from Greeks or Romans, classical sources suggest otherwise:

- Diodorus Siculus (Bibliotheca Historica, V, 74): “The Pelasgians were the first to invent the use of letters and taught them to the Greeks.”

- Titus Livius (Ab Urbe Condita, I): “Evander, a wise man from Arcadia (Pelasgian), brought letters, language, and customs to Latium.”

- Pliny the Elder (Naturalis Historia, VII, 56): “Letters were brought to Italy by settlers from Arcadia, who established themselves in Pallantium before the foundation of Rome.”

These testimonies indicate that the letters later known as “Greek” or “Latin” derive from an older Pelasgian source shared by the Illyrians.

3. Use of Pelasgian Letters by Illyrians

3.1. Southern Balkans:

Southern Illyrians, particularly in regions later colonized by Greeks, used Pelasgian letters, which evolved into the alphabets later identified as Doric, Arcadian, or Corinthian. These archaic letter forms correspond with those on the “KAICY” mosaic.

3.2. Northern Balkans:

Northern Illyrians and Italic peoples (Messapians, Daunians, Japigi) employed scripts similar to the Etruscan alphabet, which also derives from the Pelasgian cultural tradition.

4. Mosaic as Evidence of Linguistic and Graphical Unity

The mosaic’s combination of letters demonstrates:

- An ancient Albanian-speaking language (the word KAICY has meaning only in Albanian).

- An alphabet shared across multiple civilizations (Greek and Latin), but rooted in an older Pelasgian/Illyrian substratum.

This is not coincidental; it is epigraphic evidence that Illyrians were not passive users of writing but active bearers of an indigenous writing tradition.

Conclusion

The inscription “KAICY” is more than decorative; it is silent testimony to a historical truth denied for centuries. The Illyrians and Pelasgians had their own writing system, later adopted by the Greeks and Romans. The fact that only modern Albanian renders its meaning clearly demonstrates both the linguistic continuity of Albanian from Illyrian and its shared heritage with Pelasgian writing.

References

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, Libri V.

- Titus Livius, Ab Urbe Condita, Libri I.

- Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, Libri VII.

- Herodotus, Histories, Libri II.

- Giuseppe Sergi, The Mediterranean Race, 1901.

- Nermin Vlora Falaschi, Albanët dhe Pellazgët.

- Kol Marku, Studime historike mbi origjinën pellazge të shqiptarëve.

Note: Readers are encouraged to form their own conclusions, discuss, and share responsibly while respecting authorial rights.

Kol Marku – Italy, 22 March 2025

Kol Marku continues:

Abstract

Archival discoveries from the Vatican reveal that Albanian-language writing and education persisted continuously for over five centuries, from the mid-16th to the early 20th century, despite Ottoman attempts to suppress them. Between 1555 and 1746, Albanian students were trained at the Illyrian Colleges of Loreto and Fermo in Italy, while the Urban College under the Propaganda Fide also educated Albanians from Arbëria, Tivari, and Kosovo. Clergy, particularly Jesuits and Franciscans, played a crucial role in founding and maintaining schools, producing seminal works such as Andrea Bogdani’s grammar, the Meshari of Gjon Buzuku, and dictionaries and doctrinal texts by Frang Bardhi and Pjetër Bogdani. Archival evidence demonstrates the continuous operation of Albanian-language schools across Shkodër, Ulqin, Durrës, Tivar, Stublla, and other regions, including institutions for girls and public education. These findings challenge the misconception that Albanian literacy began only after the Manastir Alphabet (1908), highlighting the resilience of Albanian language, culture, and education under Ottoman rule.

Discoveries from the Vatican: Albanian Writing over Five Centuries

Between the 1600s and 1700s, 206 Albanian students were trained in Albanian language studies at the Illyrian Colleges of Loreto and Fermo in Italy, which remained operational until 1746. Andrea Bogdani, in his handwritten grammar addressed to “Dear Arbënor,” wrote a text that, even four centuries later, can easily be transcribed into contemporary Albanian. Hundreds of similar documents fill the historical gap caused by the absence of Albanian writing during five centuries of Ottoman rule.

According to scholar Mark Palnikaj, there is substantial evidence that Albanian schools and the Albanian language continued without interruption over these centuries. He argues, based on a series of archival documents in an interview with the newspaper Shqiptarja.com, that Albanian educational institutions persisted under Ottoman rule until 1905, when Albanian-language schools were formally established. While the Ottomans sought to suppress Albanian language and schooling, Albanians sacrificed and maintained them, becoming guardians of their cultural identity.

Palnikaj expresses particular enthusiasm for discovering documents evidencing Albanian-language schools across Shkodër, Skopje, Montenegro, and Preveza, from the 1500s to the 1900s. During archival research in the Vatican, he noted both known and previously unknown schools and documents, filling gaps in historical understanding.

The Role of the Clergy in Albanian Education

Palnikaj emphasizes that early Albanian schools were often run by clergy. While some scholars have minimized the role of these institutions, labeling them “religious schools,” such a perspective is inaccurate: across Europe, the earliest schools were founded and managed by religious institutions. In Albanian-speaking regions, only clergy possessed the necessary education to teach Albanian effectively. Most were Albanian, though occasionally non-Albanian clergy contributed significantly.

Notable figures include Barleti, Beçikemi, Dhimitër Frangu, Buzuku, Bardhi, and Bogdani, who during the 16th and 17th centuries produced foundational works such as the Meshari, Latin-Albanian dictionaries, doctrinal texts, and historical accounts of national hero Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu.

Early Albanian Schools: Chronology and Impact

The first Albanian school in Stublla, Montenegro, was established in 1584 and continued until 1 February 1905, when it gained administrative independence from Letnica. The date 5 February marks the beginning of the second semester of the 1904–1905 school year and is celebrated in the Statute of the Viti municipality as Albanian School Day.

Contrary to popular belief that Albanian writing began after the creation of the Manastir Alphabet in 1908, archival documents demonstrate that Albanian-language education existed continuously from at least the mid-16th century. For instance, the prestigious Illyrian College of Loreto, opened in 1555, trained clergy for service in Ottoman-occupied Albanian territories, both for the Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholic rites. Similarly, the Illyrian College of Fermo, opened in 1663, operated until 1746, enrolling Albanian students from the aforementioned regions. Several graduates attained episcopal positions within Albanian dioceses.

In 1627, the Urban College under the Vatican’s Propaganda Fide opened, educating Albanians from Arbëria, Tivari, and Kosovo. The exact number of graduates is unknown, but archival evidence confirms a significant Albanian presence. After an 1837 agreement between the Austrian Empire and the Vatican, Albanian students were also sent to study in Austrian universities.

The Jesuit Contribution

Jesuits played a crucial role in Albanian education, establishing schools across Europe and Albania. Their approach laid the foundations of modern European education, emphasizing structured curricula, free education, and access for children from poor families. Key Albanian scholars such as Frang Bardhi and Pjetër Bogdani benefited from these institutions, contributing significantly to Albanian literacy and scholarship.

Continuity of Albanian-Language Schools under Ottoman Rule

Documentary evidence shows Albanian-language schools operated continuously despite Ottoman oppression:

- Schools in Shkodër (1416), Ulqin (1258), Durrës (1278), Tivar (1349), Pult (1367), Drisht (1396), and others during the 15th–18th centuries.

- The Stublla School (1584), Kurbini School (1632), Shkodër School (1638), Pllanë School (1638), Troshan School (1639), and others.

- Female and public education initiatives, including the first Albanian-language secondary school and teacher-training institutions in the 19th century (e.g., Motrat Stigmatine, 1879).

Archival evidence demonstrates that Albanian-language education persisted uninterrupted for five centuries, culminating in fully Albanian-language schools following the Albanian National Awakening in the early 20th century. These findings challenge the misconception that Albanian literacy began only after the 1908 Manastir Alphabet, instead revealing a long-standing tradition of Albanian-language instruction maintained by clergy and educators across generations.

Conclusion

The continuous operation of Albanian-language schools and the production of Albanian texts over five centuries confirm the resilience of Albanian literacy under Ottoman rule. From early grammar manuscripts by Andrea Bogdani to later Jesuit and Franciscan initiatives, Albanians ensured the survival and development of their language, culture, and educational institutions, providing a rich and uninterrupted historical record of Albanian intellectual and cultural life.

Lulzim Osmanaj continues:

THE OLDEST ALBANIAN TEXT FORGOTTEN BY THE ACADEMY OF SCIENCES. THE BELLIFORTIS TEXT AND THE EARLY ALBANIAN OF 1332

Franz Bopp first recognized the Indo-European character of Albanian in 1854. The fundamental change that has occurred in the phonology and morphology of the language since the Indo-European period is, however, difficult to trace due to the lack of texts dating back to the fifteenth century.

From a reference made in 1332, we know that Albanian was written in Latin letters in the fourteenth century, but no data from that period have yet come to light. The fifteenth-century texts are listed in my article on Arnold von Harff’s Albanian lexicon, 1497. One text which has been interpreted as early Albanian and if so, would be the earliest record of the language of all, is the so-called Bellifortis text in ms. 663, p. 153v, preserved in the Musée Condé of the Château de Chantilly north of Paris.

The manuscript itself, dated 1405 AD, is a largely Latin work dealing with military engineering and weapons by the German pyrotechnician Conrad Kyeser (1366-1405).

The text we are dealing with consists of a total of eight lines interwoven into a somewhat mysterious Latin text on the last page of the manuscript. It was interpreted as Albanian and was actually translated by the Romanian engineer Dumitru Todericiu with the collaboration of Professor Dumitru Polena (Bucharest) in 1967 and was referred to as an early Albanian text in Götz Quarg’s edition of the Bellifortis manuscript in the same year. The text is also briefly mentioned by Dhimitër Shuteriqi in his work on Albanian sources from 1332 to 1850. The following reading can be considered final:

1 est hoc lucibulum signorum duodecim pulchrum

2 puseo virgineus aptetur die solari

3 hours mane prima tenens circulare sinistra

4 corporis dyaphoni sed dextra facculam sumat

5 et circumscriptum duodecies pronouncement

6 intervallo deposito postea require petitum

7 preascriptum presentens est hoc subtile probatum 8 noscit qui intelligit sufficit expressio simplex

9 prescriptosque ligant duodecim altitudines celi

10 nec non et virtutes queque continentur in ipsis

11.-Albania….due racha yze inbeme zabel chmielfet dayce dayci

12.-Albania….dayze yan yon yan

Albania…. pusionis dextram ragam aurem sed sinistram

14.Albania…… echem pronunciation totiens sit reiterando

15 donec compleveris corporis dyaphoni normam

16 postea ligabunt enoch et helias prophete

17 nec non magisterium summum invocatum prescriptos

Albania……ragam ragma mathy zagma concuti perbra

19.Albania……ista aus auskar auskary ausckarye zyma bomchity

20.Albania……wasram electen eleat adolecten zor dorchedine

21.Albania……zebestmus lisne zehanar zehanara zensa

22.Albania…..echem biliat adolecten zeth dorchene zehat stochis

23.Albania…….lisne zehanar zehanara zehayssa

24 strictum quod est supra recludes virginea cera

25 similiter policem unguis dextri pusionis

26 manu quoque dextra teneatur rotundum ut supra

27 quod as gravatur super eque sinistram

28 sit et unda fluens de qua complebis quesitum 29 deo gracias

Possible variant readings:

Albanian-English

11 ch.. elves

19 bonichity

20 dorchediye

21 zebestinns, zebestinus

1 This is the beauty of the twelve shining signs.

2 The virgin boy should be initiated on a sunny day in the

3 first hour in the morning, holding the round thing in the left hand 4 of (his) disharmonious body, but in the right hand he may take up a torch, 5 pronouncing twelve times that which is paraphrased.

6 After an interval, look for what is being sought after,

7 ascribed earlier. Present is the subtle thing which is being tried.

8 He who understands, knows it. A simple expression is sufficient. 9 And may the twelve heights of heaven, and also the virtues which 10 are contained in them, obey the prescribed things.

13 Pronounce (in) the right ear of the boy ‘ragam,’ but (in) the left

14 ‘echem’ as often as it should be repeated,

15 until you fulfill the norm of the disharmonious body.

16 After that the prophets Enoch and Elijah and the high priesthood 17 which has been called upon, will bind the prescribed things.

24 The stiff thing which is above, you should enclose in virgin wax, 25 in the same way the thumb of the boy’s right claw. 26 Also in the right hand the round thing may be held as above, 27 and if it gets heavy, in the same way over the left hand.

28 May there be a flowing wave at which you will fulfill the requested.

29 thank you

(a) due racha yze inbeme zabel chmielfet,

(b) dayce dayci dayze,

(c) and yon and,

(d) variety ragma mathy zagma,

(e) concuti perbra ista,

(f) out of award award award,

(g) winter bomchity,

(h) wasram electen eleat adolecten zor dorchedine zebestmus lisne zehanar zehanara zensa,

(i) echem biliat adolecten zeth dorchene zehat stochis lisne zehanar zehanara zehayssa

yze OAlb. izë = star

sabel Alb. sable = grove, forest

and Alb. janë = are (3pp)

yon Alb. jonë = bear

variety Alb. variety = rock

mathy Alb. i madh = big

perbra Alb. përbri = nearby

from Alb. afsh = ardor

wasram Alb. vashëri = group of girls

echem Alb. ehem = I sharpen, prick (fuck?)

biliat OAlb. biliat = the girls

Due to the incantatory nature of the text, we interpret the word ragam as “strong” (like a rock) and echem as “qij,” the cilat of these, according to lines 13 to 14, are pronounced in the boy’s ears as a binding of a single spirit. The incantatory nature and the rest of the text, however, preclude a word-for-word translation. The history of the tradition of the manuscripts can also provide data to reconstruct our Albanian connections.

Yesterday Bellifortis and today held a meeting to discuss the party’s commitment to strengthening the liberal arts and martial arts. In the evening, the eight books and engineering works of the mrekullive and the streets of Weimar, RDGJ (Ms. fol. 328), were the first to discuss the visa time of the Bellifortis. In Northern Crimea, the city of Warsaw in the early 1590s, the most famous heroic warrior, Skënderbeut (rreth 1405-1468) and the cili e bleu, were born in the city of Ferdinand of Aragon.

This world is not a rastësi, but a world that shqipfolësit was written in France in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, with the same text. In the spring of 1269, Karli and Anzhuit sailed to Vlorë to meet him in Albania. The anzhuinève in Shqipëri received a machine and the 14th of the results did not convert the people of Shqipëri to Catholicism. There are also Catholics, who have agreed with the French clergy and the command shqip, that they should not go to France for Frankët u larguan.

References

ELSIE, Robert

The Albanian lexicon of Arnold von Harff, 1497. in: Zeitschrift für Verglejende Sprachwissenschaft 97 (1984), p. 113-122.

KYESER, Conrad from Eichstatt

Bellifortis. Umschrift und Übersetzung von Götz Quarg (Düsseldorf 1967).

SHUTERIQI, Dhimitër S.

Shkrimet shqipe në vitet 1332-1852 (Tiranë 1976).

STADTMÜLLER, Georg

Universal Folk Beliefs and Christianization in Albania. in: Orientalia Christiana Periodical 20 (1954), p. 211-246.

TODORICIU, Dumitru

The oldest Albanian text? in: Contemporanul 24. xi. 1967 (Bucharest).

TODORICIU, Dumitru

An older Albanian text describes the formula of baptism from 1462. in: Magazin Istoric 8 (1967), p. 8284. Society of historical and philological sciences of the Socialist Republic of Romania (Bucharest).

TODORICIU, Dumitru

An unknown Albanian text inserted in a medieval manuscript of military technology written at the beginning of the eleventh century. in: Studia Bibliologica 2 (1967), p. 311-325. University of Bucharest. Institute of Pedagogy – Faculty of Philology. Sectia de biblioteconomie (Bucharest).

Arben Llalla writes:

Abstract

This article examines the epigraphic research of Niko Stilos, highlighting the earliest traces of Albanian writing preserved on ancient inscriptions and manuscripts. Stilos argues that Albanians, particularly Arvanites and Tosker/Gegë groups, are autochthonous in the Balkans and that their language and script predate classical Greek traditions. Evidence includes bilingual dictionaries, pre-1555 manuscripts, and inscriptions in Doric dialects deciphered as Albanian. Stilos’ work demonstrates that the Doric inscriptions of Crete correspond to the Tosk dialect of Albanian, while the Ionian communities reflect Gegë speakers. Historical sources, such as 13th-century Latin accounts, confirm the existence of Albanian-language books written in Latin script. These findings challenge long-held assumptions that Greek or Latin were the exclusive languages of antiquity in the region. By analyzing inscriptions, manuscripts, and linguistic continuity, Stilos reconstructs a narrative in which Albanian language, literacy, and culture persisted for centuries, providing vital evidence of Albanian autochthony and its contribution to European linguistic history.

“Niko Stilos and the Earliest Traces of Albanian Writing: Epigraphic Evidence from Ancient Doric Inscriptions”

In general, the history of the ancient Albanian people has been recorded mostly by foreign scholars, who often studied and presented research on Albania’s antiquity. However, there have been instances in which these scholars concealed or misinterpreted evidence. The Greek scholar of Albanian origin, Niko Stilos, published several years ago the book “The Sacred History of the Arvanites” in Albanian, a work demonstrating the antiquity of the Albanian language and script. One year ago, he also published the bilingual Greek–Albanian Dictionary of Marko Boçari.

At the age of 19, Markoja produced the first Greek–Albanian dictionary, consisting of 111 pages, 1,494 Albanian words, and 1,701 Greek words. The original is preserved at the National Museum of Paris (Supplement Grec 251, page 244), donated in May 1819 by the French consul in Janina, Pukëvilli.

Niko Stilos was born in a village of the Preveza prefecture to bilingual Albanian–Greek parents (Arvanite). For over 30 years, he has conducted prehistorical linguistic research on the antiquity of European languages. Holding a degree in economics from Italian universities, he later emigrated to Germany, where he has lived for more than 35 years. For decades, he has studied ancient inscriptions, arguing that Albanians are autochthonous in ancient Greece, representing the ancient Hellenes rather than modern Greeks. He supports these views with epigraphic evidence and statements by ancient historians such as Herodotus.

Stilos emphasizes that most Albanians lack awareness that the language of antiquity was Albanian and that there exist ancient Albanian texts. Historically, attention has been placed on Greek as the language and script of antiquity. He stresses that many Albanian texts existed well before 1555, the year traditionally associated with the publication of the Meshari. For example, a 13th-century Catholic bishop in Bari noted that Albanians had a language distinct from Latin, yet their books were written in Latin script.

Stilos also discusses the Doric inscriptions discovered in Crete, which he has deciphered as written in Albanian, specifically the Tosk dialect of the Arvanites. He proposes that the Doric dialect inscriptions represent Tosk Albanians, while the Ionians correspond to Gegë Albanians. Both dialects existed in antiquity, with Gegë speakers later writing Albanian using Latin letters. Stilos has deciphered inscriptions in Perugia, Tuscany, and other regions in Albanian using both Latin and Greek letters. He aims to make this knowledge accessible to Albanians in Greece (Arvanites) and worldwide, challenging nationalist narratives that deny Albanian cultural and linguistic continuity.

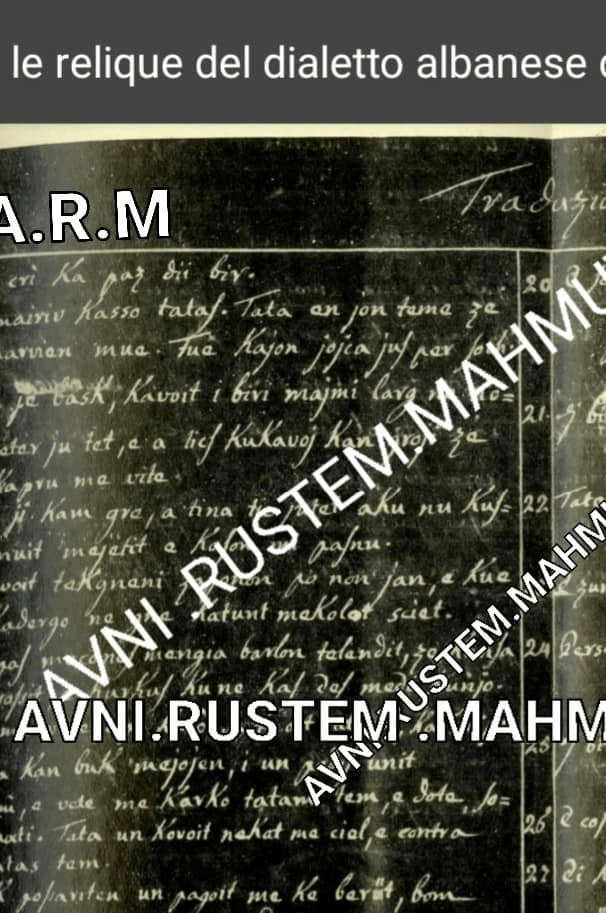

Avni Rrustem Mahmutaj writes:

Abstract

This study examines a unique 1835 biblical fragment written by Pietro Matija Stankovic in the lost Istrian dialect of Albanian. Stankovic, a priest and historian from Barban, eastern Istria (Croatia), is the only known author to preserve this dialect in writing. The Istrian dialect, a now-extinct branch of Gheg Albanian, emerged between the 13th and 17th centuries due to population shifts and Venetian colonization of Istria, which brought Albanian settlers and combined various dialectal features. The fragment, titled The Child’s Tears, illustrates linguistic features, vocabulary, and syntax specific to the Istrian Albanian dialect. By transliterating the text into contemporary Albanian, this work enriches the historical corpus of Albanian and provides insight into regional dialect diversity. The research highlights the importance of preserving minor dialects and contributes to understanding the spread of Albanian in the western Balkans, offering a rare glimpse into the language’s historical and sociolinguistic development.

“The Lost Istrian Dialect of Albanian: Pietro Stankovic’s 1835 Biblical Fragment”

Yesterday, I addressed a question regarding the lost Istrian dialect of the Albanian language. This dialect is preserved in a biblical fragment written by Pietro Matija Stankovic in 1835.

Pietro Stankovic was born in Barban, a small commune in eastern Istria (present-day Croatia). He was a priest, historian, and inventor, and is the only known author to have written a text in the Istrian Albanian dialect. The fragment is titled The Child’s Tears, and it remains the sole surviving text in this dialect.

The Istrian dialect was a now-extinct variety of Albanian spoken in the Poreč plains of Croatia until the late 19th century. From the 13th to the 17th century, due to depopulation of the Istrian peninsula, the Venetian Republic repopulated the region with various groups, including Albanians. The interaction of these groups and dialects resulted in the formation of the Istrian dialect, classified within the Gheg branch of Albanian.

According to Italian scholars, parts of Istria were historically inhabited by Albanians, and small Albanian-speaking villages persist to this day. The fragment will be presented here both in its original form and transliterated into contemporary Albanian to enrich the Albanian linguistic corpus.

Original fragment with modern Albanian transliteration:

- GNI ERI KA PAS Dİİ BIR – One man had two sons.

- EJ MAIRIU KASSO TATAS. TATA EN JON TEME ZE PARNON MUE – And the younger, Kaso Tatas, his father would not accept me.

- TUE KAJON JOJCA JUS PER SOCH KAVU JE BASK – (He?) cried, (you?) for his companion whom he had been with.

- KAVOIT I BIRI MAJMI LARG NE NOTETER JU TET. E A LICS KUKAVOJ KAN GROJI ZE KAPRU ME VITE – The father and son were far apart during the nights; the harsh circumstances continued for years.

Further study is required to fully contextualize and interpret the text, as has been done with other Albanian writings.

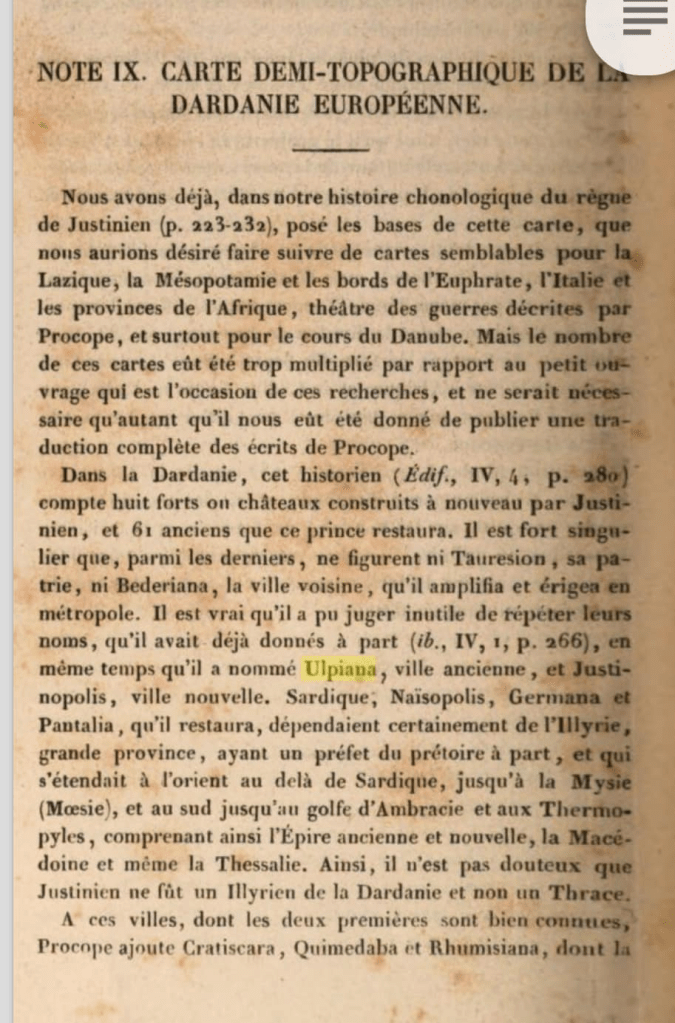

Luljeta Rakipi writes:

Abstract

This study examines historical claims regarding the European Dardania region, the Illyrian origins of Justinian, and the extent of Illyrian influence in the Balkans. Drawing on a publication from Paris (1856) and subsequent translations, the text highlights Kosovo as the heart of European Dardania and identifies Mitrovica as the ancient Dardanian capital. Justinian is presented as a true Dardanian Illyrian who fortified the Danube against Slavic incursions and enacted extensive legal codices. The work also addresses the historical geography of Epirus, Mysia, Dacia, and Macedonia, the dual Dardania regions in Asia and Europe, and the alliances Justinian formed with Noricum, Paneonians, and Lombards against the Goths. Urban centers such as Scutari, Lissus, and Epidamnus reflect the political and cultural presence of Illyrians in the Balkans. This research contributes to the understanding of Illyrian political structures, regional identities, and Justinian’s legacy in European and Balkan history.

“Illyrian Dardania and the Legacy of Justinian: Historical Geography and Identity”

Published in Paris in 1856, this book vividly illustrates the extent of ancient Illyria. The text emphasizes that Kosovo corresponds to European Dardania, the homeland of Justinian, whose nephew is associated with modern Germany. The ancient capital of the Dardanians was Mitrovica. Justinian himself was a true Dardanian Illyrian.

Regions such as Thessaly, Epirus, Mysia, Dacia, and Macedonia were historically divided. Justinian constructed large and strong fortifications along the Danube to protect against the Slavs. Liqenydos (Lychenidos) was the lake of the Albanian Epirotes, heavily impacted by an earthquake. Cities like Scutari, Lissus, and Epidamnus (modern Durrës) were part of the territory of the Epirotes in “New Epirus.”

There were two Dardania regions: one in Asia and one in Europe—the latter corresponding to Justinian’s birthplace. Justinian became not only Metropolitan of the archbishopric but also a leading figure of all Illyria. Historical records indicate he authored numerous laws and codices and allied with Noricum (Nürnberg), Paneonians, and Lombards against the Goths. The Illyrian capital was Firmitana, later Vindobona (Vienna).

Vullnet Xhango writes:

Abstract

This paper analyzes a possible early Albanian inscription on the Midas Monument at Yazılıkaya, Eskişehir Province, Turkey. The site, abandoned by the Phrygians around 500 BCE, features remains of a significant Phrygian settlement and a monument dedicated to King Midas. The first line of the inscription, transliterated from the original script using the Shkronjat e Elbasanit, reads KEΛoKEZ FENAFTYN AFTAZMATEPES, which can be interpreted in modern Albanian as “KËDOKËND QË NA FTOJNË ATA NË MATERE” The study examines linguistic continuity between Indo-European languages, proposing that the term matere may reflect a semantic link to “motherhood” or “home” in Phrygian. These findings support the hypothesis that early Albanian or related Indo-European dialects may have been used in inscriptions as early as the 6th century BCE, providing evidence for the historical depth of Albanian linguistic presence in the Balkans and Anatolia.

“Yazılıkaya and the Frigian Monument: An Early Albanian Inscription in the Midas Monument?”

“WELCOME GATE” is the most fitting name for the monument in the photograph. The text is written in Albanian. It features words resembling those found in Indo-European languages. Readers are invited to explore and judge.

Yazılıkaya, a village in Eskişehir Province, Turkey, is an archaeological park that preserves Phrygian remains. Archaeological evidence indicates settlement in the area dates to the Early Bronze Age, although there is no evidence of continuous habitation. The Phrygians are believed to have abandoned the Yazılıkaya area around 500 BCE.

A Phrygian inscription on the monument’s façade states it was created in honor of King Midas by an individual named Ates, possibly a priest. The Midas Monument reflects the artistic and cultural achievements of Phrygian civilization.

The first line of the inscription reads:

KEΛoKEZ FENAFTYN AFTAZMATEPES

Using a transliteration table based on the Shkronjat e Elbasanit (Elbasan Letters) and word recognition, the text can be interpreted as:

KEDoKENDË FE NA FTJNË AFTA ND(ë) MATERRES

Three vertical dots were replaced by the letter “Ë,” as in the Corinthian List (noted by N. Stylos). In modern Albanian, the line is understood as:

“KËDOKËND QË NA FTOJNË ATA NË MATERE.”

The word matere (6th century BCE) may correspond to the Phrygian term for “motherhood” or “home,” suggesting early semantic continuity in Indo-European languages.

Luftulla Peza and Liljana Pez writes:

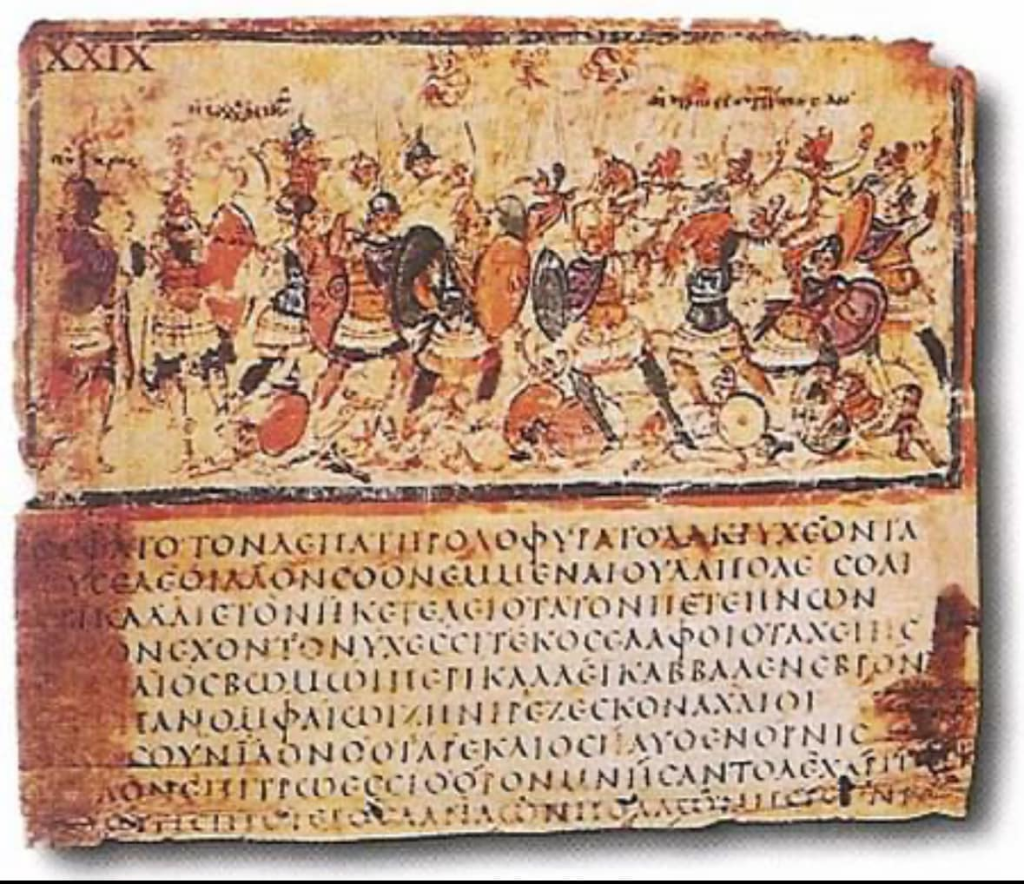

“The Iliad of Homer: Evidence for Its Composition in Ancient Lydian and Proto-Albanian”

Abstract

This study examines evidence suggesting that Homer’s Iliad, composed in the 8th century BCE, was originally written in the Lydian language, closely related to ancient Illyrian and modern Albanian. Recent research demonstrates that the text’s linguistic structure, vocabulary, and Pelasgian roots are preserved in Albanian, providing a reliable means to understand Homer’s verses. Comparative analysis of translations in 16 European languages reveals widespread mistranslation, as translators lacked knowledge of the original dialect. The epic, recounting the Trojan War (~1200 BCE) between Dardanians and the Achaean coalition, is accessible in meaning primarily through Albanian. Manuscripts written in boustrophedon style confirm the use of Pelasgian alphabetic forms. These findings suggest that the Iliad represents both the first literary work of Lydia and the earliest recorded composition in a Pelasgian-derived language, highlighting the continuity of Albanian as a linguistic descendant of ancient Anatolian and Illyrian languages.

The Iliad – Why It Was Written in Albanian: An Analysis by Prof. Luftulla Peza

The Iliad by Homer is the first major literary work and a cornerstone of European literature. According to recent research, the Iliad was written on papyrus in the 8th century BCE in Smyrna, in the ancient kingdom of Lydia on the western coast of Anatolia. Our findings suggest that the language of Homer’s Iliad was Lydian, a dialect closely related to other ancient Anatolian and Illyrian languages, as well as to modern Albanian. This close affinity stems from all these languages originating from the ancient Pelasgian language.

Homer was a poet of Lydia, and his work represents the first literary production of ancient Lydia. Since the Lydian language became extinct, understanding the Iliad today requires Albanian, which preserves linguistic features of Pelasgian origin. The original Lydian alphabet was later supplemented by the Arvanites in Athens and additional letters in Alexandria.

A comparative study of 16 European translations—including Albanian, Greek, English, French, German, Italian, and Turkish—shows significant mistranslations. Translators, unfamiliar with Homer’s original dialect, produced works that often do not correspond to the original verses. The verses can be properly understood only through Albanian due to its Pelasgian roots.

The Iliad narrates the ancient Dardanian city of Ilion (Troy), celebrating the heroism of warriors during the Trojan War (~1200 BCE). The epic describes battles between Pelasgian groups and Troy’s defenders, including King Priam and Prince Hector, and the invading Achaean coalition, led by Agamemnon. The first word of the Iliad, traditionally cited as Greek “menin”, is, according to our research, Pelasgian/Albanian in origin.

The text of the Iliad is preserved in numerous manuscripts, often written in boustrophedon style, reflecting archaic Pelasgian letters. A detailed transcription of over 300 lines shows that Homer’s dialect aligns with the Albanian Gheg dialect, demonstrating its Pelasgian linguistic heritage.

Shefqet Cakiqi-Llapashtica writes:

Abstract

The Albanian language represents a vital component of global cultural heritage, tracing its roots to the Pelasgians and Illyrians. Historical, linguistic, and genetic studies confirm that Albanian preserves elements of this ancient civilization, making it one of the oldest Indo-European languages in Europe. Misinterpretations by traditional linguistics often underestimate its antiquity, considering it a derivative language; however, evidence from pre-Greek inscriptions, such as the Cippus Perusinus (3rd–2nd century BCE), demonstrates early written use. Comparative analyses reveal close linguistic relationships between Etruscan, Phrygian, Lydian, Epirot, Thracian, Macedonian, Trojan, and Illyrian dialects, unified in Albanian. These findings indicate that Albanian preserves original Pelasgian structures, predating Greek, and supports its recognition as an independent, historically continuous language. Protecting and promoting Albanian through UNESCO’s frameworks is essential for safeguarding this unique linguistic heritage.

“Albanian Language: A Global Heritage and Its Ancient Roots in Etruscan and Pelasgian Civilization”

Albanian Language: World Heritage, to be Protected by UNESCO

All studies, for many centuries, provide evidence that the Albanian ethnicity descends and is preserved from antiquity: the Pelasgians, as the mother of most of the world’s ethnicities. The Albanian language is an ornament preserved from this antiquity, and recent discoveries in genetic science confirm these theses.

“Ancient humanity spoke today’s Albanian language. The Albanian language, of Pelasgian-Illyrian origin, is the Indo-European mother language, from which its daughters were later born, the old and the new languages.” — Altin Kocaqi

“Shared words in European languages and in a dialect of Sanskrit became the cause for the birth of comparative science: Indo-European studies. This science concluded that these shared words come from the same mother language once spoken in a certain region, but to this day we do not have a single opinion about that region.

The eye of the linguist, in comparative science, examines European languages based on the earliest linguistic documentation and determines that if there are shared words between two European languages, then the language documented later borrowed from the one documented earlier.

According to our linguistics, the Albanian language is documented later than many neighboring languages; therefore, in etymological dictionaries, it is considered a language that borrowed words from its neighbors to form itself. In this work, I will present documents concerning the earliest documentation of Albanian words, building upon the strong foundations of the European linguistic tradition.

The original remains of the language of the Pre-Greeks, the Pelasgians, are indisputable linguistic indicators showing the existence of the Albanian language, older than Greek itself, and consequently altering the logic of the linguist’s perspective regarding Albanian.

Like all European languages, which have borrowed and lent words to one another based on historical developments, Albanian has also borrowed words from neighboring languages in later times.

If we compare these borrowings without considering history and the earliest documentation of the words of a language, we reach distorted and incorrect conclusions. Therefore, this work aims to clarify the role of Albanian among the European sister languages. The basis of this work will be the original remains of the language of the Pre-Greeks = Pelasgians, preserved through the documentation in ancient dictionaries.” — Altin Kocaqi

The Albanian Language Written 300 Years Before Christ

“L’Idiome Pélasgien dans l’Europe Méditerranéenne”

Report by Nermin Vlora Falaschi

Etruscan writing on the stone slab called the “Cippus Perusinus” is the first writing in the Albanian language in the 3rd century BCE.

Cippus Perusinus is an Etruscan stele from the 3rd or 2nd century BCE, and it served as a reference point. The stele took its name from the location where it was found in Perugia and is now housed in the National Archaeological Museum of Umbria in Perugia. The fourth-longest text in the Etruscan language is engraved on the stele.

The travertine stele is 1.49 meters high, 54 cm long, and 24.5 cm wide. It was discovered in 1822 on San Marco hill near Perugia. The base of the boundary stone is expanded and roughly smoothed. Initially, it was placed below the ground surface so that only the polished upper part of the stele was visible. Cippus refers to an Etruscan grave stone.

The inscription is written in Etruscan script with letters typical of northern Etruria between the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE. As was customary in Etruscan writing, the inscription is read from right to left. Often, there is a line break within a word, e.g., V-ELTHINA on line 15/16 and TH-AURA on line 20/21. In total, the inscription consists of 46 lines with about 125 words.

The front surface contains 24 lines, divided into four paragraphs, distinguishable by spaces at the end of the left side of paragraphs in lines 8, 11, and 19. In the first line, the letters are larger than those below, with one letter missing on the left and right. In line 12, the text is cut on the right and appears to follow line 13 in content.

The side area consists of 22 lines. Words are separated here by a dot, while dots are used only on the front to mark special passages. A correction was made in line 9 on the lower left of the page, and a letter was erased again.

According to French researcher Zacharie Mayani:

“These are Indo-European-based languages spread in Asia Minor. Furthermore, the Etruscan language is not of eastern origin. Its origins lead us toward the Danube.

The Etruscans are partly descendants of the Tursha. But the Tursha are not a people of eastern origin. They are ancient Illyrians (or Thraco-Illyrians) settled in Asia Minor. We have already mentioned these facts in various contexts and now bring them back.

The precursor groups of a people seeking to create a new homeland across the sea are generally numerically small. Examples of the Hyksos, Philistines, Carthaginians, and Normans are sufficient. It is difficult to believe that the contingents of the Tursha, who arrived from the Aegean-Anatolian region, could have been sufficient to establish a broad ethnic base for the founding of the future confederation of the “twelve peoples of Etruria.”

The majority of the Illyrian population of the region must have already been there before the arrival of the Tursha, who were under the influence of Lydian-Hittite civilization. When we speak of this population, we have in mind the embryo of the Illyrian nation. It belonged to a broad family of peoples connected mainly by language rather than any other element.

This family included: Epirotes, Macedonians, Thracians, Phrygians, Etruscans, Veneti, Liburnians, Picenes, Japigi, Dardanians, Trojans, Lydians, perhaps some Cretans, Teucrians, Philistines, Jebusites, and many others.

Historically, to determine their origin, we can follow a common path leading to the Danube area, thus limiting the location of their oldest known homeland.

Nevertheless, the decisive feature that distinguishes this Illyrian population above all is undoubtedly its language. This language is essentially Indo-European. It seems to have borrowed some elements from the languages of Anatolia and the Caucasus but has assimilated these influences much less than Hittite or Armenian. Indeed, it has revealed many similarities with Balto-Slavic languages. Its origin cannot be found elsewhere except in a region between the Carpathians and the Danube.

G. Battisti recently raised the issue of Illyrian and argued that it was initially connected with the Cretan-Aegean center, but later there was a superimposition of Indo-European dialects.”

THE FIRST ALBANIAN LANGUAGE

Similarities between Etruscan and Albanian.

According to French researcher Zacharie Mayani, the Phrygians, Lydians, Etruscans, Epirotes, Thracians, Macedonians, Trojans, and Illyrians spoke the same language: Albanian.

Similarities between Etruscan and Albanian language. According to the French scholar Zacharie Mayani, Phrygians, Lydians, Etruscans, Epirotes, Thracians, Macedonians, Trojans, and Illyrians spoke the same language: Albanian.

Muharrem Abazaj writes:

NO ONE CAN OBSTRUCT THE CONFIRMATION OF THE ALBANIAN LANGUAGE

(Another supplementary document. 2500-year-old Albanian writing)

The written documentation of the Albanian language does not go beyond the 16th century. Despite continuous efforts, it has not been possible to find any earlier document. This has caused the Albanian language to be classified as a relatively new language. Its vocabulary has been crippled by considering many of its words as borrowings from other languages, and as a result, the antiquity of our nation in these lands has been questioned.

Under these circumstances, the only reference source to make it possible to know ancient Albanian remains the ancient inscriptions.

A large number of inscriptions have been found in various places, and fortunately many of them are preserved. In the overwhelming majority, these inscriptions have remained undeciphered.

Many Albanian and foreign scholars have tried to decipher them using the Albanian language. Mr. Manjani, R. d’Anjeli, N. Falaski (Vlora), N. Stylo, etc., have expressed the belief that they have identified Albanian words in these inscriptions. But perhaps their lack of deep knowledge of the Albanian language, especially of its dialects, did not allow them to equate the text of these inscriptions with the Albanian language.

Like many other scholars, I have tried for many years in a row to decipher them. I have managed to decipher many such inscriptions, found not only in our country but also in various places such as the Mediterranean basin, the Balkan Peninsula, Italy, and elsewhere. The inscriptions I have deciphered are written in the period when the alphabet began to be used and go up to the 8th century BCE.

It is understandable that writing was used many centuries earlier and has a long history of development. It began to be written through figures, then through various hieroglyphs, including cuneiform. Even for inscriptions written before the alphabet was created, attempts have been made to decipher them. There have also been claims that some inscriptions have been deciphered. But we do not have a single case where these decipherings were linked to the Albanian language.

The inscriptions I have deciphered have several common characteristics: they are written with a special alphabet, their writing is continuous, without separation between sentences and words, without punctuation; the writing starts from the right moving to the left. But what is very important for us is that all these inscriptions can be deciphered only through the Albanian language.

The obvious question anyone would have about this statement is: “How can this fact be explained, when all these inscriptions, most of which are found in places far from Albania, can be deciphered with the Albanian language?”

For almost three centuries, Albanian and foreign scholars have insisted on the thesis that the Albanian language derives from Pelasgian. The Pelasgians, as the oldest people known to history, inhabited a very wide territory. It is precisely this connection, this linguistic continuity Pelasgo-Illyrian-Albanian, that is concretized in this fact: the possibility of deciphering them only through the Albanian language.

Among the inscriptions I have deciphered, I highlight one found on the island of Lemnos in Greece, as it is dated as very early, the 8th century BCE.

In the literature, this inscription is known as the “Lapidary of Lemnos.” It is written in the so-called Phoenician alphabet, but it is more correct to call it the Pelasgian alphabet. It consists of 22 letters, among which 5 vowels (a, e, i, u, o). Its text, as a dedication on a gravestone, is very short. It describes the killing of a person in a conflict over land ownership. But the few words written there are words of ancient Albanian (Pelasgian).

I have focused the work of deciphering especially on Etruscan inscriptions, as they are numerous (there are nearly 13,000 of them) and some have relatively long texts, giving the possibility not only to identify the forms of many words of ancient Albanian but also to understand its grammatical structure.

From the six inscriptions with relatively extended texts, I have deciphered three of them: “Lamina di Perugia,” “Tegola di Capua,” “Cippo di Perugia,” and I have published them in the book “The Ancient Albanian Language (Pelasgian)”. The linguistic material of these inscriptions is fully sufficient to conclude that the modern Albanian language is a continuation, an evolution of Pelasgian.

But from the responsible institutions (respectively the Academy of Albanological Studies), there has been no reaction, even negative or opposing. When they are not interested in these fundamental issues of Albanology, such as the origin of the Albanian language and at the same time the ethnogenesis of our nation, why do they retain that prestigious name, the Academy of Albanological Studies?

We are determined to bring further even more resounding evidence, in the hope of not leaving this institution in the coma it has fallen into.

I have just finished another of these inscriptions with extended texts, which I am making known in this post.

This inscription is known as “Disco di Maliona.”

It was found in Tuscany, in the Province of Grosseto, in 1882. It is dated to the 5th–4th century BCE. It is preserved in the Archaeological Museum of Florence.

Before providing its detailed deciphering, we introduce you to the ancient Albanian words used in this inscription, as well as the content of this inscription.

This inscription also has an epigraphic character, and as a result, its vocabulary is poor, but there we find many words which are very valuable, as they are root, word-forming words of the Albanian language.

As you will notice below, all the words of ancient Albanian were monosyllabic. They had rigid, unchangeable forms. This is explained by the fact that ancient Albanian, at that low stage of development, did not have functional grammatical tools such as prefixes, suffixes, prepositions, and distinctive markers. Ancient Albanian had only three verbal endings: m, n, t/s. This rigidity of word forms caused the same word to take multiple meanings.

For example, the word di took the meaning of the verb di (to know), of the numeral di/dy (two), of dhisë di (sheep), of the process of excretion di, etc. The word mar took the meaning of the verb marr (to take), of the adjective i mbarë (complete), of the person i marrë (mad), etc.

Words of Ancient Albanian

Nouns:

- am: means the name “mother,” in the Gheg dialect form am, e ama.

- men: the name “mind,” in Gheg dialect men.

- dial: the name “boy.” The consonant j is not found in any case in inscriptions.

- ud: means the name “road.” Ancient Albanian did not write double consonants: t/th, s/sh, l/ll, d/dh, etc.

- si: means the name “eye.” In some regional dialects, the vowel i is still used instead of y: dy/di, krye/krie, etc.

- hal: means the name “trouble.” (I > ll)

- Hi: means the name “God” (Zoti). In modern Albanian, it evolved as follows: the vowel i became y, giving hi > hy. When Albanian became a flektive language, in the definite form, the vowel i was placed and the form hyi emerged; a consonant j was inserted between vowels, producing today’s Hyji.

Adjectives:

- mad: means “great.” Ancient Albanian did not have inflected adjectives. For example, the adjective i badhë was written bard (Bardhyl, white star).

Pronouns:

- un: first person singular, “I.”

- ti: second person singular, “you.”

- i: third person singular masculine, “he.” The modern form comes from combining the ancient singular verb a (asht) with the third person pronoun i: a+i > ai.

- o: third person singular feminine, “she.” Formed by a+o > ao, with j inserted for hiatus, giving modern ajo.

- ki: second person singular masculine demonstrative, “this one” (i>y).

- ko: third person singular feminine demonstrative, “this one.”

- im: first person singular possessive, “my.”

- mu: short form of pronoun (Gheg) “me/mue.”

- ma: short combined form of pronoun (më + e > ma).

Verbs:

- a, as, ast: all three forms mean “is” in Gheg.

- di: “to know.”

- ik: “to go.” Suffixes and endings are not reflected in writing.

- se: “to see” (s>sh).

- nin: “to hear” (Gheg: ndejn).

- ran: “to go” (Gheg: ra, me shkue), third person singular.

- ul: “to sit.”

- la: “to leave.”

- za: “to take” (Gheg: zan).

- da: “to divide” (Gheg).

- hud: “to throw” (Gheg: dh).

- nit: “to unite” (Gheg: njit, n>nj).

- em: “to be” (Gheg: jem).

- fen: “to sleep” (Gheg).

- ben: “to fall” (Gheg).

- pen: “to strike” (Gheg).

- fa: “to say.”

- fil: “to call” (f>th).

- ad: “to come” (Gheg).

- in: “to stay” (Gheg: rrin).

- mi: adverbial particle, “well.”

- ma: adverbial particle, “still” (Gheg).

- sal: adverbial particle, “only,” used in epic: “Në ma dhensh motrën Hajli, sall (only) një natë ta mbaj në ship” (Gjergj Elez Alija).

- bef: adverbial particle, “suddenly.”

Conjunctions:

- e: additive “and.”

- a: selective, “or.”

- s: causal, “because.”

Particles:

- s: negation.

- sk: negation “no, not.”

- n: conditional “if” or negation “not.”

- sun: negative particle “s’” and semi-auxiliary verb “cannot.”

CONTENT OF THE INSCRIPTION

First Disc (right)

A mother with her child is traveling at night. At one moment, the mother leaves the child alone on the road and leaves.

The author does not explain why the mother leaves her child, but from the content it can be understood that the mother went somewhere nearby, perhaps to a sacred place, to pray to God, maybe for this child, and did not want the child present during this prayer.

- “Më la ama, ran, da,” he says. He was left alone by his mother on the road and she left. As he moves along the road, he cannot see his mother. He is calling out:

- “Mirë mendja më shkoi. Madh,” he says.

“He calls God ‘the Great,’ just as we Albanians also call God ‘the Great God.’ For the Etruscans, it was not called God but Hy (Hyji).”

- “Where are you going? Do you see, Hyji, I know,” he continues walking. He does not know what to say to God.

- “Here I am, Hyji. Let him feel me, his eyes see me,” he walks along talking.

- “I cannot sit, Hyji,” he says. He jumps, leaps upward. Cannot stay in the air.

- “I said I will jump, I am alone,” he says, desperate.

- “I am going to sleep,” he says, as sleep overcomes him.

- “Should I stay, should I not play? I don’t know, Ef,” the child faces a great dilemma.

Second Disc (left)

The child apparently decided not to stay in one place. He begins to move again along the road. He walks and calls:

- “Why, o Hyji, so dark? Why, my Hyji, has my mother left me?” he complains about the darkness and the mother leaving him alone.

He trembles, is startled. He no longer calls. - “Have I lost him? He doesn’t know me and doesn’t hear me?” says the frightened child.

Trouble has taken hold of him. - “Was he together, and now is separated?” he begins to doubt his actions.

- “He was leaving the mind,” begins to detach from reality.

- “To God, climb up there, he was there. My Hyji, he has left me, he left me,”

- “He cannot stay up there,” so he says, “You would jump up, but you are alone. My Hyji, call me, for Hyji, you see, you know the path,” he is losing consciousness.

- “He, Hyji, he, ut, ef,” he almost completely loses consciousness, speaking half words without connection.

Falls. Sits, sleeps. And as he leaves, the mother comes.

Here the inscription ends.

My note: With the expression “ai ik” (the child), the author indicates that this child has passed away, has died. In every case we have encountered in ancient inscriptions, when a person dies, it is not said “died” but “went, left, left life.”

Detailed Deciphering

The following is the detailed deciphering. Reading begins from the disc on the right, as every Pelasgo-Albanian writing starts from the right to the left. To help follow the deciphering, we first replaced the letters of the Pelasgian alphabet with the corresponding letters of the modern Albanian alphabet, made approximate sentence separations, then separated the words of each sentence. For each ancient Albanian word, we gave the corresponding modern Albanian form. At the end of the deciphering of each word, we provided its meaning in Albanian.