by Etnor Canaj. Translation Petrit Latifi

Abstract

This study examines the archaeological and historical evidence surrounding the Basilica of Ballsh in Mallakastër, Albania, focusing on two central figures: Prince Boris of Bulgaria and the Norman knight Robert Monteforte. The analysis incorporates inscriptions from a limestone slab discovered in 1918, archival documents, and scholarly sources to reconstruct the Christianization of the Bulgarians under Prince Boris (Michael I) and the Norman military presence in the region during the late 11th and early 12th centuries. The study highlights the integration of epigraphic, historical, and archaeological data to provide new insights into medieval Balkan political and religious dynamics.

Part 1: Introduction and Reflection

Without intending to be polemical, I would like to note the following: research on this historical figure, Robert Monteforte, although sometimes claimed and appropriated by those holding questionable doctorates, must be considered in its original context. The works in which the only three sources regarding this figure are found possess a context that only the original author of the present text fully understands.

(A few years ago, I confronted the mentor of the individual who had appropriated my work, reminding him that one may steal whatever they wish, yet it takes little for an opponent to put you in an uncomfortable position.)

This work was originally published by me in 2017. In 2018, a team of so-called “Albanian researchers” (those who set the rules there) copied the portion I had presented as exclusive and claimed it as their own.

Part 2: The Land of Basilicas – Mallakastër, Where the Bulgarians Converted and the Normans Fought

“E la disme est de Balaide fort

ço est une gent ki unches ben ne volt. Aoi…”

(La Chanson de Roland)

1) The Inscription and the Bulgarians

During World War I, the Austrian archaeologist and researcher Camillo Praschniker, in his field expeditions and archaeological studies, made an interesting discovery at what is today known as the Basilica of Ballsh in the Mallakastër region. This site is significant both historically and archaeologically.

According to researchers, the Basilica of Ballsh was a Christian building not belonging to the late antique period (paleochristian church), but based on its layout and construction technique (K. Zheku, Monumentet, Vol. 2, 1987, p. 97), it likely dates to the early Middle Ages (8th–10th centuries CE).

Returning to the discovery, Praschniker published his study in 1922 under the title Muzakhia und Malakastra, included in volumes 21–22 of Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Institutes in Wien, published in Vienna in 1922.

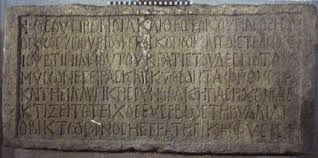

On pages 195–196, Praschniker reports the following information regarding this discovery (Fig. 1): a limestone slab measuring 160 cm in length and 40 cm in width was found in the ruins of the church in Ballsh, Mallakastër, in 1918. The upper part of this slab bears a Greek inscription:

“– – – – – –

– – Μαρίασ

Βόρης ό μετο-

νομασθείς

Μιχαήλ σύν

τό έχ θεού δε-

δομένω αύ-

τώ ἕθνει ἕ-

τους, ςτοδ’.”

(C. Praschniker, Muzakhia und Malakastra, Vienna, 1922)

In the work of historian, scholar, and publicist Ilirjan Gjika, who cites Praschniker and other authors, this Greek text is translated as:

“Prince Boris of Bulgaria, who had taken the name Michael, was baptized together with his people by God in 866”

(I. Gjika, Bylisi i Ilirise dhe Apollonia e Jonit, 2010, Ymeraj Publications, Fier, p. 35)

Thus, the upper portion of the slab contains an inscription linked to what is known as the “Bulgarian conquests” in Mallakastër, where Prince Boris of Bulgaria, along with his people, embraced Christianity and received the name Michael I. The baptism, performed in the Byzantine rite of the Eastern Orthodox Church, likely took place in the Church of Saint Mary, as indicated by the inscription, despite damage to the upper part of the slab, where the name of the Mother of Christ (Maria) is visible.

According to medieval historian and Byzantinist Georg Ostrogorsky, Prince Boris of Bulgaria converted to Christianity in 864 CE with the blessing of the Byzantine emperor and received the name Michael because Emperor Michael III served as his godfather. The Greek/Byzantine clergy immediately began organizing the Bulgarian Church following this conversion (G. Ostrogorsky, Storia dell’Impero Bizantino, 2005, Einaudi, p. 210).

This interpretation is further supported by André Vaillant and Michael Lascaris in their study La date de la conversion des Bulgares, published in 1933 in Revue des Études Slaves, Vol. 13, No. 1, who rely on the inscription found in Ballsh to reach this conclusion.

Indeed, according to Gjika, King Boris of Bulgaria sent Saint Clement as a missionary to expand the influence of the Bulgarian Church and its institutions in Ohrid, Devoll, and Gllavenica (likely Bylis). Albanian scholar Koço Zheku confirms that Gllavenica is in fact Bylis, both as a fortified center (castrum) and a religious site. Other sources indicate that no other sites in southern Illyria had comparable military or ecclesiastical significance.

From Dhimiter Homatian’s writings (Archbishop of Ohrid, first half of the 13th century), in his work Short Biography, we learn:

“In Gllavenica, several stone pillars remain to this day, bearing inscriptions marking the union of the Bulgarian people with Christ.”

(Theofan Popa, Gllavinica e lashtë dhe Ballshi i sotëm, Studime Historike, Nr. 2, 1964, pp. 235–241; Jordan Ivanov, Bëllgarski Starini iz Makedonia, Sofia, 1931, pp. 318–319)

This historical evidence corresponds convincingly with Praschniker’s inscription from the Basilica of Ballsh. In the land of the Bylis people, the Bulgarians were converted to Christianity under their prince, Boris, baptized as Michael I.

Part 3: The Inscription and the Normans

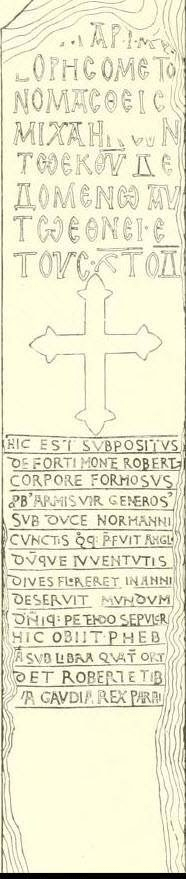

The second portion of the epigraphic slab is particularly notable for a centrally carved cross, typical of Norman iconography and also a symbol associated with crusaders during the Crusades, campaigns undertaken primarily by Western and Northern Europeans beginning in the 11th century (the First Crusade began in 1094 under Pope Urban II).

Historical sources, particularly Anna Komnene, indicate that the Normans arrived in this region at the end of the 11th century with the arrival of Robert Guiscard and military actions in 1107–1108 along the lower Vjosa River. Gllavenica is recorded as a fortified site defended by Byzantines (Komnene mentions Aliates), and Koço Zheku’s descriptions correspond fully with the identification of Gllavenica as Bylis (Koço Zheku, Glavinica dhe problemi i lokalizimit të saj, Monumentet, Nr. 2, 1987, p. 101).

The epitaph of the Norman knight Robert Monteforte (or Monte Forte) consists of 14 lines in poetic Latin. He served under the commander of the First Crusade, Bohemond I of Taranto and Antioch. The Latin inscription reads:

“Hic est subpositus

de Forti Monte Robert(us),

Corpore formosus,

prob(us) armis, vir generos(us).

Sub Duce Normanni(s)

cunctis quoq(ue) praefuit Angli(s),

Deseruit mundum

Dominque petendo sepulc(um)

Hic obiit Phoeb(o)

(i)a(m) sub Libra quater orto.

Det Roberte tib(i)

(s)ua gaudia rex para(disi).”

(C. Praschniker, Muzakhia und Malakastra, 1922, Vienna)

Translated into English:

“Here lies Robert Monteforte,

handsome in body, valiant in arms, noble of character.

Subduke of the Normans,

leader over all English warriors.

In the prime of youth, he abandoned the world

to seek the tomb of the Lord.

When he died young,

as the sun rose for the fourth time,

may the King of Paradise grant you, Robert, his joys.”

Further archival evidence confirms Monteforte’s service alongside Bohemond I. In Jean Paul Migne’s Patrologiae Cursus Completus, we find:

“Bohemund, with the assistance of Robert de Monteforti and many other barons, undertakes an expedition against the Emperor of Constantinople. The death of Marcus Bohemund. Antioch is defended by Baldwin against the Saracens.”

(J. P. Migne, Patrologiae Cursus Completus: Series Latina, Vol. 188, 1855, pp. 819–820)

In translation:

“Bohemond, with the aid of Robert Monteforte and other barons, prepared the campaign against the Emperor of Constantinople. Bohemond died. Baldwin defended Antioch against the Saracens.”

Additionally, Melville Madison Bigelow documents:

“In the year 1107 of the Lord, King Henry summoned his nobles and reprimanded Robert de Monteforti for violating his oath. Consequently, feeling guilty, he received permission to go to Jerusalem and left all his lands to the king.”

(Placita Anglo-Normannica, 1974, p. 94)

Thus, initially Robert Monteforte hesitated to join the campaign organized by King Henry I of England. Upon feeling remorse, he was granted permission to participate, while his estates were placed under the king’s authority.

A particularly noteworthy document is a letter from Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury (1033/34–1109), informing the faithful of Robert Monteforte’s death:

“Epistle 475, To all the faithful of the Church of Christ.

Anselm, bishop of the Holy Church of Canterbury: greetings and the blessing of God and my own to all the faithful. Know that Robert de Monteforti recently died on the road to Jerusalem…”

(Franciscus Salesius Schmitt, Opera omnia, Vol. 3–6, 1938, p. 423)

This letter communicates Robert Monteforte’s death to his homeland, delivered by one of the most prominent ecclesiastical figures of the period, Archbishop Anselm of Aosta. It implies that Monteforte was likely from southern England, where he held estates.

There is some chronological uncertainty: the letter is dated 1102, but other sources indicate Monteforte died on September 20, 1108. It is unlikely that two individuals of the same name died en route to Jerusalem, suggesting that the 1102 date may be incorrect.

Furthermore, Robert Monteforte may have held the title Magister Militum, indicating a high military command; however, further verification is needed to confirm these historical details:

“Magistrum militiam Robertum de Monteforti” (as commander in 1098)

Part 4: Conclusion

Considering all archaeological and historical elements:

- The Ballsh slab is a unique material witness to the Christianization of the Bulgarians under Prince Boris, baptized Michael I, corroborated by both inscriptions and historical sources.

- Robert Monteforte, a Norman knight and subduke, was commemorated with a substantial limestone epitaph in a preexisting church (likely Saint Mary in Ballsh), demonstrating the Norman reuse of sacred spaces for memorial purposes.

Future archaeological research will help to further corroborate and expand upon these historical findings.