Translated and edited by Petrit Latifi, 2025

Abstract

This article presents the results of rescue archaeological excavations conducted at the prehistoric settlement of Hisar in Suhareka during 2023–2024. The investigations revealed a multilayered site with continuous occupation from the Late Neolithic through the Hellenistic period. Cultural layers from the Eneolithic, Bronze Age, Iron Age, and Hellenistic period were identified, including habitation features, production zones, and rich ceramic assemblages. The findings confirm Hisar as a major regional center, demonstrating extensive cultural connections with the Balkans, Greece, and Southern Italy, while preserving strong indigenous Dardanian traditions in settlement organization, architecture, and material culture.

Publisher

Archaeological Institute of Kosovo, Prishtina, 2025

Editorial Board

Editor-in-Chief

Shafi GASHI

Editorial Staff

Premtim ALAJ

Zana RAMA

Elvis SHALA

Milot BERISHA

Secretary

Bardhyl REXHEPI

Table of Contents

Vesel Hoxhaj

Cultural Characteristics of the Neolithic Period in the Prizren Region

Zhaneta GJYSHJA, Bardhyl Rexhepi, Michael L. GALATY, Premtim ALAJ

The Lluga Archaeological Project: The Late Neolithic Site at Vrella, Istog Municipality

Erina Baci, Premtim Ala, Bardhyl Rexhepi, Michael L. Galaty, Brett Stewart, Julian Shultz

Preliminary Results of Archaeological Investigations at the Settlements of Lubozhda and Syrigana in Western Kosovo

Shafi Gashi, Klodian Velo, Berat Ademi, Sali Islami

New Data from Archaeological Excavations at Hisar, Suhareka

Berat Ademi

An Ancient Settlement in the Village of Bajë

Premtim Alaj, Bardhyl Rexhepi

The Fortress of Lubeniq

Luan Gashi

The Lost Grave of Pjetër Bogdani (1630–1689): A Historical and Archaeological Investigation from a Multidisciplinary Perspective – p. 161

UDC: 902.2(496.51-13)(05)

1. Introduction

The prehistoric settlement of Hisar is situated on a hill terrace, forming the final segment of a chain of hills on the southern side of the town of Suharekë. The first data concerning this settlement emerged in the 1950s, when agricultural activities in the area revealed archaeological materials that were later studied by archaeologists.

The first systematic excavations were carried out by J. Todorović between 1961 and 1963¹ and by J. Glišić in 1978. Regular stratigraphic excavations conducted between 2003–2004 and again in 2007 by Sh. Gashi and A. Bunguri provided important information about the development of life at this settlement.

As a result of these investigations, a multilayered site was identified, with evidence demonstrating continuous habitation from the Late Neolithic through the Hellenistic period². This article presents the most recent results from excavations conducted at Hisar during 2023–2024 by the Institute of Archaeology of Kosovo. These represent two rescue excavation campaigns undertaken before private development projects were initiated in the area.

¹ Todorović 1963, pp. 25–29; ² Bunguri and Gashi 2006, pp. 11–20.

2. Excavation Campaigns (2023–2024)

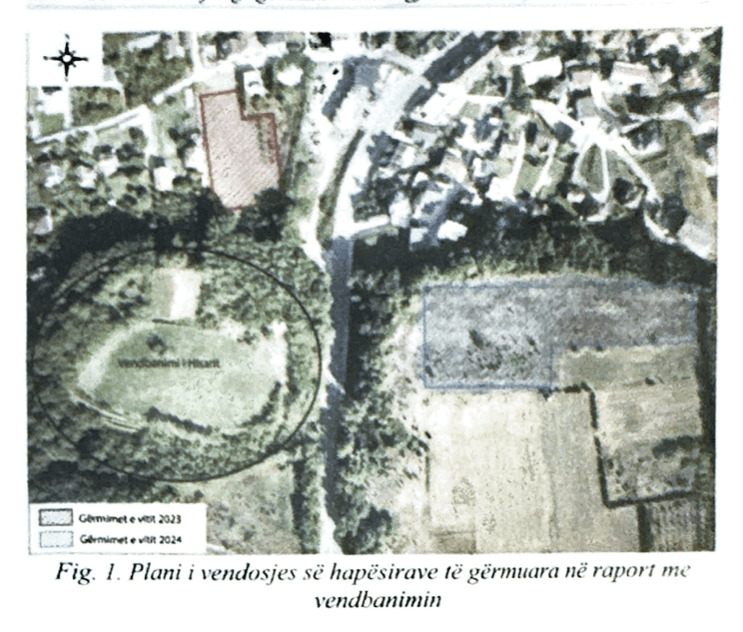

Both campaigns were part of rescue archaeology projects preceding private construction. The 2023 excavations, covering about 1,500 square meters, were conducted on the northern side at the base of the hill settlement, while the 2024 excavations, extending over roughly 3,000 square meters, took place on its eastern side. After removing the agricultural layer, the excavations proceeded only in areas where cultural deposits were observed.

3. General Results

The excavations revealed cultural deposits and archaeological material belonging to the Eneolithic (Copper Age), Bronze Age, and Iron Age, continuing up to the Hellenistic period. The 2023 deposits were found in a horizontal stratigraphy across a few squares containing material from the Bronze and Iron Ages.

In contrast, the 2024 campaign, carried out on flat terrain east of Hisar (Fig. 1), revealed deposits concentrated in pits and three trenches. A small proportion of the material belonged to the Early and Middle Eneolithic (Hisar IIa–b phases), while about seventy percent of the pits contained Late Eneolithic deposits of the Hisar IIc type, associated with the Baden–Kostolac cultural group of the Central Balkans. Bronze Age layers were identified only in the 2023 campaign, whereas Iron Age materials appeared in both of the most recent campaigns.

Figure 1. Plan showing the excavated areas in relation to the Hisar settlement.

4. Late Eneolithic Layers

Archaeological deposits from the Late Eneolithic were identified in only three excavation squares during the 2024 campaign on the eastern side of the settlement (Squares 33, 52–53). This suggests that habitation during the Early and Middle Eneolithic was concentrated mainly on the terrace of Hisar.

These deposits were found within large pits, two of which were overlain by Late Eneolithic deposits. Based on their size and form, some of these pits may have been used as dwellings. They were dug into the ground and served as shelters for people, providing protection from wind, rain, and predators.

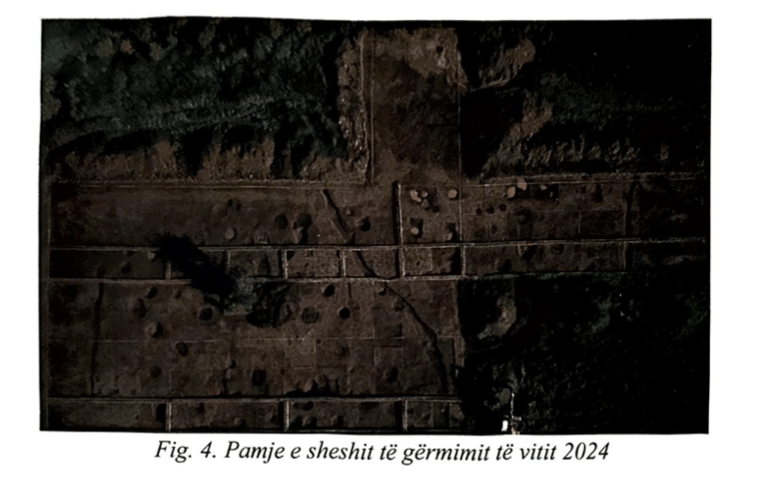

In some cases, they were covered with branches, animal hides, or other decomposable materials, forming primitive dwellings apparently used for short periods. Approximately fifty pits of various shapes and sizes were discovered, filled with archaeological material (Fig. 4).

5. Interpretation of Pit Features

The pit itself and the material that filled it should be considered separately, as the original purpose of a pit may not have been related to the material that later filled it, even if that fill helps explain why it was originally dug. In prehistoric contexts, pits were simple but multifunctional structures used for a variety of purposes depending on the needs of the inhabitants.

Cylindrical pits and traces of groundwater levels may indicate wells. Oval pits with sloping bases deeper on one side could have been used for clay extraction for construction or pottery production. Shallower pits with concave bases might have served as storage areas for food. Once these structures went out of use, they were filled with refuse materials belonging to the same chronological phase.

6. Archaeological Material

Most of the archaeological material from this period came from the fills of the pits. It consists primarily of fragments of ceramic vessels, including storage jars, cooking pots, and tableware. Common vessel forms include S-profiled shapes, occasionally decorated with broad, oblique fluting on the shoulders; rounded vessels; and small S-profiled plates (Tabs. II–III).

This material belongs chiefly to the Hisar IIa phase. The material culture of Hisar IIa–b is comparable to that of settlements such as Vlashnje, Dejç i Klinës, Gadime e Epërme, and Budrigë e Poshtme in Gjilan. Similar features appear in settlements of the Morava basin and the Skopje region. The Hisar IIa–b culture also corresponds to the Neziri cave settlement in the Mat valley and to Maliq IIa–b³ in Albania.

³ Bunguri 2006; Gashi 2012.

7. Late Eneolithic Group Hisar IIc – Baden–Kostolac Culture

The Late Eneolithic pits of the Hisar IIc group, corresponding to the Baden–Kostolac culture of the Central Balkans, were concentrated exclusively on the eastern side of Hisar. The deposits contained abundant material recovered from well-defined stratigraphic contexts. Among the finds were deep pots with slightly conical bodies, decorated with horizontal bands impressed with fingertips; large S-profiled vessels, often ornamented with aligned triangles filled with punctured dots and incised lines, sometimes coated with white paste; and numerous conical plates with pillow-shaped or sharply triangular inward-slanting rims decorated with lines, a characteristic feature of the Kostolac group.

Small S-profiled bowls were often decorated with incised lines and dimples on the shoulders, and cups with strip handles raised above the rim were also common. For the first time, pseudobarbotine pottery appears in this phase, continuing into the Early Bronze Age Hisar IIIa phase, which corresponds to Maliq IIIa. Judging from the material culture, Hisar represents the southernmost station reached by the Baden–Kostolac cultural group as it spread from Central Europe toward the southern Balkans.

8. The Bronze Age

Bronze Age layers were identified in both excavation areas, though they dominated in the 2023 northern sector and appeared less frequently in the 2024 eastern area. Archaeological finds from this period include fragments of vessels, loom weights, tools, and remains of dwellings. The material culture of this period is clearly datable. Storage vessels are dominant and appear as conical-bodied pots (tenxhere), pirranoi-type containers, and Korishë-type vessels of various sizes.

Conical single-handled bowls of different dimensions were also found, many featuring axe-shaped handles typical of the Middle Bronze Age, continuing through the Late Bronze Age and with some variations into the Early Iron Age (Tabs. IV–V). In the Late Bronze Age, conical plates with thickened inward-slanting rims decorated with fluting become dominant. These are known as “turbandish-type” vessels, a decorative style that became even more common in the Early Iron Age.

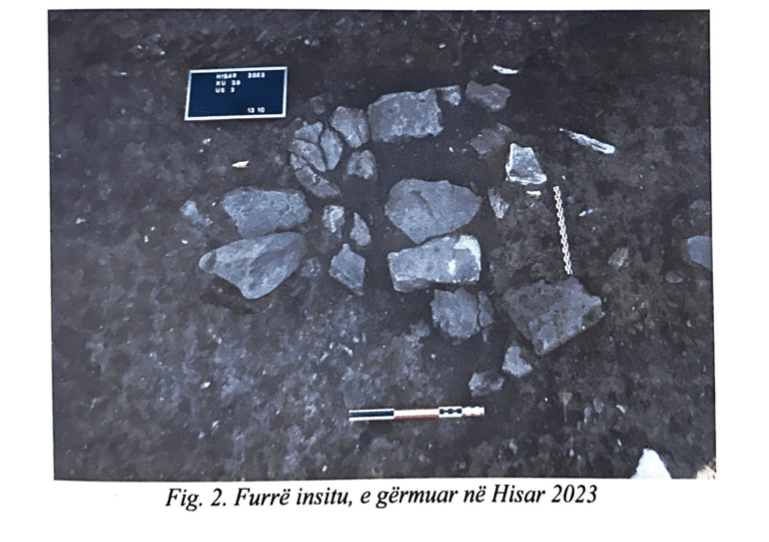

9. Cooking Installation

A particularly important find from this period was a food-cooking oven discovered in situ, dating to the Late Bronze Age. The remains of the oven were uncovered during the 2023 excavations on the northern slope of the Hisar hill (Fig. 2). The structure had been built upon a foundation of small and medium river stones.

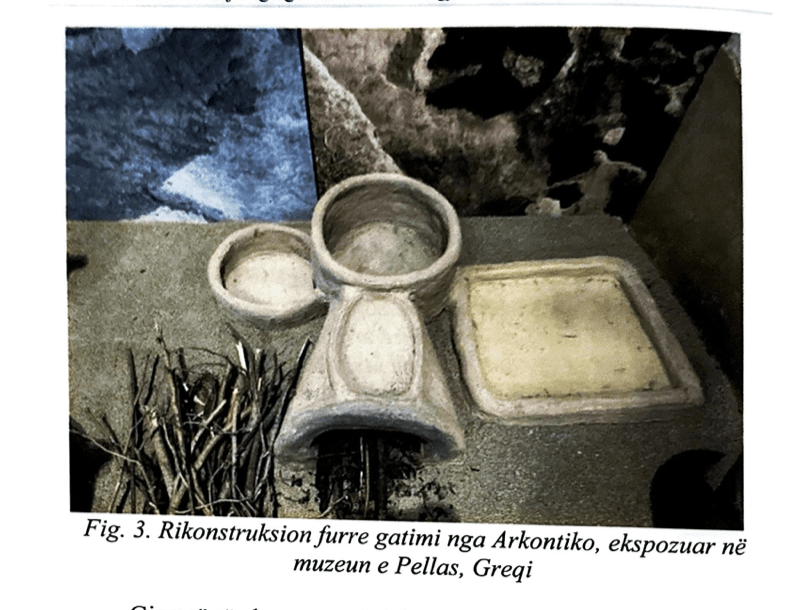

The preserved remains included the hearth area used for food preparation and a rectangular tray that had served for baking food. A similar oven is exhibited in the Archaeological Museum of Pella, Greece (Fig. 3), reconstructed from the Bronze Age settlement of Arkontiko in northern Greece. Analysis of the surrounding archaeological context indicated that this oven was situated in an open area, not within a dwelling, suggesting that food preparation and cooking in Hisar at this time took place outdoors.

Figure 2. Cooking oven in situ, excavated at Hisar 2023.

Figure 3. Reconstruction of a Bronze Age cooking oven from Arkontiko, exhibited at the Archaeological Museum of Pella, Greece.

10. Iron Age Features

Numerous traces of human activity dating to the Iron Age were documented in both excavation areas, represented by material spanning the entire chronological range of this period. In addition to the ceramic finds, stratigraphic evidence was observed in the form of cuts made in the terrain during the 2024 excavation in the eastern sector (Fig. 4). These included channels and trenches of different sizes. One, oriented north–south, may have served as a boundary element for part of the settlement, possibly functioning as a small defensive ditch. Two shallower channels may have been used for drainage.

Figure 4. View of the 2024 excavation area, showing pits and channels.

Other traces consisted of pits with various functions: some used for food storage, others for water collection as wells, and some for extracting raw clay or for firing pottery. After they went out of use, all were filled with refuse, including broken pottery, damaged architectural debris, and other domestic waste. Similar pit features have also been found in Iron Age contexts at the sites of Dobratina and Zhegoc.

11. Iron Age Material

The Iron Age material consists mainly of ceramic fragments used for storage, food preparation, and serving. Compared with the Bronze Age, there is a notable increase in the number of cooking pots of varying sizes, fewer examples of pirranoi-type vessels, and a predominance of large S-profiled vessels with rounded outward-turned rims. Conical plates are frequent, decorated with dimples, wide oblique fluting, and facetting; double-handled bowls are also common. For the first time, vessels decorated with toothed-comb incisions appear.

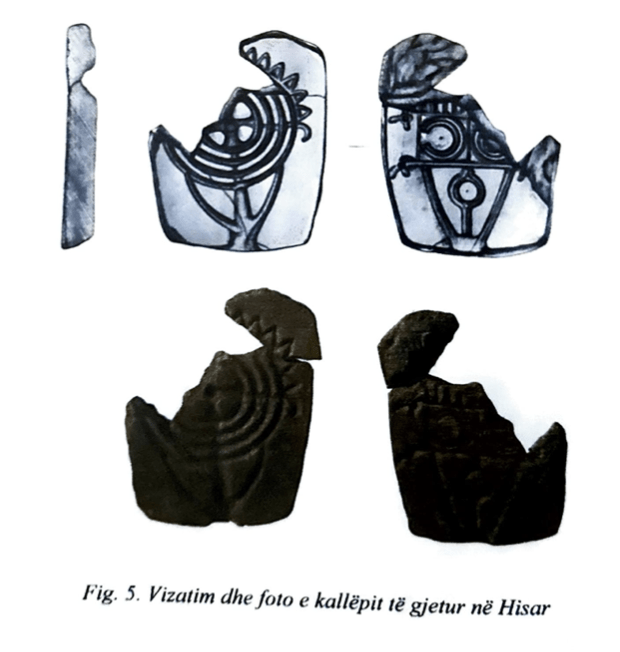

A particularly significant discovery was made during the 2024 excavations in the eastern area of the settlement, within the fill of an Iron Age pit: three stone molds. The pit also contained debris from furnaces and slag residues. On one side of the largest mold was engraved the design of a pendant consisting of concentric circles connected to each other, with the outermost circle decorated with a serrated pattern of small triangles (Fig. 5).

These molds were used for casting bronze or iron and producing pendants. Although this is the only example of its type found in Hisar, evidence of metallurgy at the site dates back to the Neolithic Hisar IIb phase, including a flat-axe stone mold, a bone awl with a copper tip, an axe of the Jásládani type, and two ceramic casting vessels (Gießgefaß) for molten copper.

Figure 5. Drawing and photograph of the stone mold found in Hisar.

Comparable examples of such molds have been discovered in an Iron Age cemetery beneath the Roman theatre of Skopje, dated to the Early Iron Age. In one grave, identified as that of a woman, a semicircular fibula was found in the abdominal area, along with ten multicoloured glass-paste beads distributed along the chest and neck, and inside a small handled bowl near the knees was a bronze pendant formed of concentric circles similar to that depicted on the Hisar mold.

Similar finds have been recorded in Shirokë, Brazdë, Banja near Kumanovë, Radan near Shtip, and Medvegjë in southern Serbia. A related pendant was also found in an Iron Age tumulus cemetery at Stërnovc near Kumanovë. These objects are generally interpreted as cultic sun pendants, associated with solar worship, and are thought to be linked to the Dardanian tribe, as all such finds fall within the area historically inhabited by them.

12. The Hellenistic Period

The majority of finds from the Hellenistic period were uncovered in the lower northern part of the settlement. The archaeological material from this horizon is extensive and diverse, representing a complete repertoire of vessel types used for storage, cooking, and serving.

Storage jars and large pithoi were used for keeping food supplies. Cooking vessels included pirranoi-type pots, deep kitchen vessels for preparing stews, and shallow trays for baking. The tableware repertoire was particularly rich, comprising deep and shallow plates, bowls, cups, jugs, hydriae, skyphoi, and kylikes.

The manufacturing technique of these vessels followed traditions established in earlier historical periods. Most storage and cooking vessels were handmade, while tableware was produced both by hand and on the potter’s wheel, the latter technique being increasingly common during the Hellenistic period. Among the wheel-made ceramics, imported black-glazed wares and locally produced grey ceramics were found.

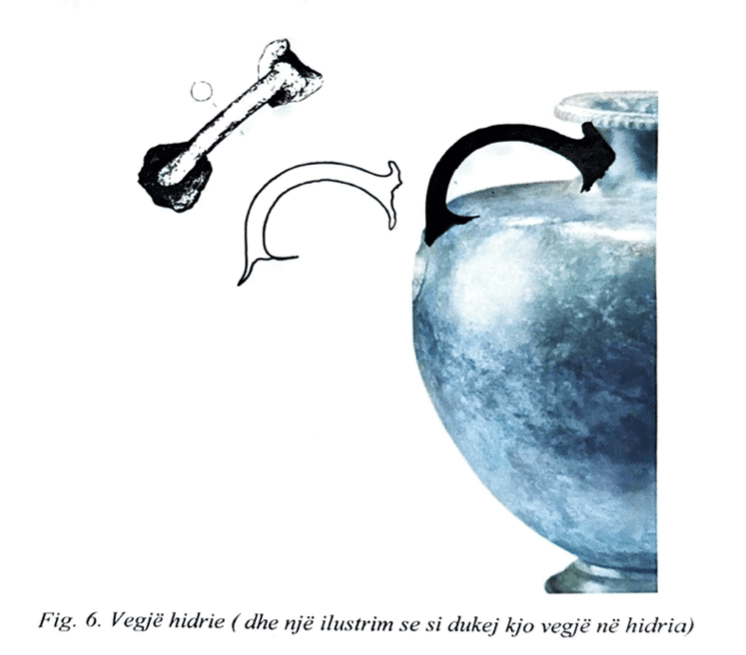

A significant part of the assemblage consists of vessels used for mixing and serving wine, typical of the Classical–Hellenistic era. Many of these were imported from Greece. Based on the clay fabric and the quality of the black glaze, some pieces can be attributed to Attic production. Among these imports, a rare find was a bronze vertical hydria handle, generally used in funerary contexts, dated to the fifth century BCE (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Hydria hook (and an illustration of what this hook looked like in the hydria)

Another notable discovery was a fragment of a vessel with a black-glazed surface and white-painted decoration, imported from southern Italy and dated to the second half of the fourth century BCE. This fragment originated from the Apulian region and belongs to the so-called Gnathia ware.

It represents the neck portion of a table vessel with a narrow mouth, glazed black on the interior and decorated on the exterior with black glaze overpainted in white. Vessels of the Gnathia type are typically adorned with simple vegetal motifs and larger figural scenes associated with Dionysus, the god of wine and theatre. On the Hisar fragment, both the black-glazed and white-painted decoration suggest vegetal motifs, possibly vine leaves, likely connected to a Dionysian scene.

These finds show that luxury objects and imported ceramics from Greece and southern Italy reached the settlement of Hisar during the Classical–Hellenistic period, bringing with them the cultural practice of wine consumption. The locally produced grey wheel-made ceramics reflect the influence of Hellenistic culture across the Dardanian territory.

This grey ware is found widely in what is today Kosovo, southern and western Serbia, and the Kumanovo–Skopje region of North Macedonia — the geographical area once inhabited by the Dardanian tribe. Consequently, the wheel-made grey pottery is considered a local production influenced by Hellenistic models.

Similar grey wares are found in southwestern North Macedonia and southeastern Albania, notably at the fortress of Pogradec and other sites around Lake Ohrid, an area once inhabited by the Illyrian tribe of the Enchelei. However, such finds are rare there and are best interpreted as evidence of trade exchange rather than local manufacture.

The Hellenistic cultural influence at Hisar also extended to textile production and domestic crafts, as indicated by the discovery of loom weights of various sizes. All this movable archaeological material clearly demonstrates the spread of Hellenistic culture in the settlement of Hisar, and by extension, in the Dardanian region.

However, one striking aspect — not only at Hisar but in nearly all Hellenistic-period settlements excavated in Kosovo — is the absence of Hellenistic influence in urban planning and architectural techniques.

Only at Novo Brdo, Bostan, and Budrigë e Poshtme have fortification walls been found that show some resemblance to southern construction methods. Social or cultural public buildings and Hellenistic-style residential houses, which are so typical in neighboring regions, are completely lacking in Dardanian territory.

At Hisar, as in most contemporary settlements, wood and wattle-and-daub walls with clay insulation continued to be used for construction during the Classical–Hellenistic period. Clay floors were common, as indicated by the remains of daub showing impressions of wooden branches and reeds on their reverse sides. The presence of these remains in the lower parts of walls also confirms the use of clay flooring. Similar evidence has been recorded at other sites of this period in Kosovo, such as Dobratinë, Ticë, and Kamenicë.

13. Conclusions

Based on the two most recent rescue excavation campaigns of 2023–2024 and the earlier investigations, the Hisar settlement can be regarded as one of the most important prehistoric centers in Kosovo and the wider Balkans. The results demonstrate clear changes in the extent and organization of the settlement across different historical periods.

During the Late Eneolithic (Hisar IIa–b and especially Hisar IIc phases), the settlement expanded mainly toward the east, an area lying on the same level as the main Hisar terrace. During the Bronze Age, particularly in its late phase, Hisar reached its greatest spatial extent, expanding not only over the earlier Eneolithic layers but also descending toward the lower northern slope of the hill, while the eastern part appears less intensively occupied. It seems that the eastern area of Hisar, from the Late Eneolithic through the Late Iron Age, functioned primarily as an industrial zone, used for clay extraction and pottery production.

The recent excavations confirm the continuity of life in this settlement from the Late Neolithic, as identified in earlier campaigns, through to the Hellenistic period. With the exception of Early and Middle Eneolithic deposits (Hisar IIa–b), which are concentrated on the terrace itself, other cultural layers have been documented beyond it, extending as far as 500 meters away — as shown by Iron Age and Hellenistic finds, including the bronze hydria handle.

The archaeological material recovered allows several important conclusions about the development of life and cultural relations of the inhabitants of Hisar. One notable result is the widespread use of wheel-made grey ceramics for tableware, particularly oinochoai, skyphoi, kylikes, hydriae, and various conical and spherical bowls. These fine vessels demonstrate a high level of craftsmanship and purity of clay. Similar examples have been documented in excavations at Dobratinë, Ticë, and the fortress of Dardana.

The study also shows that grey ceramics played a significant role in the production of tableware. However, handmade vessels continued to be produced in parallel: plates and shallow bowls remained handmade following earlier traditions, as did all cooking pots and some storage jars.

The imported finds further indicate that the inhabitants of Hisar during the Classical–Hellenistic period maintained exchange relations — perhaps indirect — with distant Greek settlements in the Aegean and southern Italy. Trade routes probably varied: some connections may have passed through Macedonia toward Greece, while imports from southern Italy likely reached the area through routes linked to the ports of Durrës or Apollonia.

14. References to Figures and Tables

Tabs. I–V: Ceramic assemblages from Hisar IIa–b (Early Eneolithic), Hisar IIc (Late Eneolithic, Baden–Kostolac group), Hisar IIIa–c (Early to Late Bronze Age), and Hisar IV (Iron Age).

Figures 1–6: Plans, excavation views, cooking oven remains, comparative examples from Pella (Greece), Iron Age molds, and imported vessel fragments.

References

Andre, J. (1983). p. 75.

Anamali, S. (1980). [Archaeological Studies on the Prehistoric Settlements of Albania]. pp. 215–216.

Bunguri, A. (2006). [Unpublished excavation report or publication referenced in text], pp. 11–20.

Bunguri, A. (2021). [Study on Hisar Excavations], p. 54, figs. 12, Tab. XXXVIII–281, Tab. LXIV–206, 207.

Bunguri, A., & Gashi, Sh. (2006). [Excavations in Hisar 2003–2004]. Prishtina: Institute of Archaeology of Kosovo.

Gashi, Sh. (2012). Archive of the Institute of Archaeology of Kosovo (IAK), Prishtina.

Gashi, Sh., Alaj, P., Berisha, M., & Rama, Z. (2017). [Archaeological Research in Dardania], p. 245.

Labate, D. (2001). [Study on prehistoric kiln structures], pp. 21–40.

Mise, M. (2015). [Gnathia Pottery: Iconography and Production], p. 4.

Mitrevski, D. (2017). [Iron Age Cemeteries under the Roman Theatre of Skopje], p. 147.

Prendi, F. (2018). [Prehistory of Albania: Studies and Research], p. 238.

Stankovski, J. (2008). [The Iron Age Cemetery of Stërnovc near Kumanovo], pp. 135–151.

Todorović, J. (1963). [Hisar Excavations Report 1961–1963], pp. 25–29.

Vasić, R. (1987). [Southern Serbia: Iron Age Finds], p. 673, Tab. LXX–10.

Velo, K., & Gashi, Sh. (2017). [Excavations at the Fortress of Dardana], pp. 794–795.

Original publication (in Albanian)