by Libri Komenti (Gjergji). Translation Petrit Latifi

Summary

This text examines how the Balkans’ historical trauma, symbolic politics, and religious identity have shaped a culture of conflict, victimhood, and myth-based nationalism. It argues that the instrumentalization of history and faith has hindered institutional development, promoted reactive identities, and sustained political manipulation. The author calls for critical demythologization, civic-oriented education, and ethical governance as necessary steps toward lasting stability and reconciliation.

Broken Geography and the Birth of the Eternal Myth

The Balkans are not merely a geographical space; they are a tense historical condition, a permanent laboratory of conflict where symbols, religions, identities, and myths have functioned for centuries as substitutes for institutions, as justifications for violence, and as mechanisms of collective survival. Nowhere else in Europe has the symbol been so heavily charged with blood, memory, guilt, victimhood, and unhealthy pride as in the Balkans. Here, history has not passed; it has remained suspended. The past is not studied but used. Symbols do not unite; they divide. Religion is not a spiritual path but a front line.

The Balkans as a Crossroads of Empires and Inherited Trauma

From antiquity to the 20th century, the Balkans were a battlefield of empires: Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, Russian. None saw the Balkans as a subject—only as an object. This produced a specific collective psychology: peoples who built states not as rational projects, but as reactions to occupation. In this environment, symbols became shelter.

The flag, religion, the mythical hero, and the historical enemy gained psychological survival functions. When the state was absent, the symbol became the state. When law was missing, myth became justice. This is the root of the Balkan problem: symbols came before institutions.

Religion in the Balkans: From Faith to Political Identity

In the Balkans, religion was rarely just a matter of personal conscience. It quickly became an identity marker, a political card, and a criterion of national belonging. Orthodoxy, Catholicism, and Islam were not merely beliefs; they were instrumentalized by empires and later by local elites to build exclusionary narratives.

The question was not “What do you believe?” but “Who are you against?” The cross and the crescent became territorial stamps. Wars were fought not for land, but for “holiness.” Massacres were committed not for interests, but “in God’s name.” Religion thus became the strongest alibi for violence because it demands no earthly accountability.

The Myth of the Victim: The Balkans’ Most Dangerous Weapon

Every Balkan nation sees itself as history’s greatest victim. This is not perception—it is doctrine. Serbs, Croats, Bosniaks, Greeks, Albanians, Bulgarians: each has built its identity on a historical wound, often frozen in time and transformed into justification for violence. In this logic, the victim can never be guilty.

And when the victim gains power, violence becomes “historical compensation.” This is why the Balkans remain cyclically violent: the past justifies the present, and the present creates new wounds for the future. Symbols here do not remember suffering to prevent repetition; they keep it alive to exploit it.

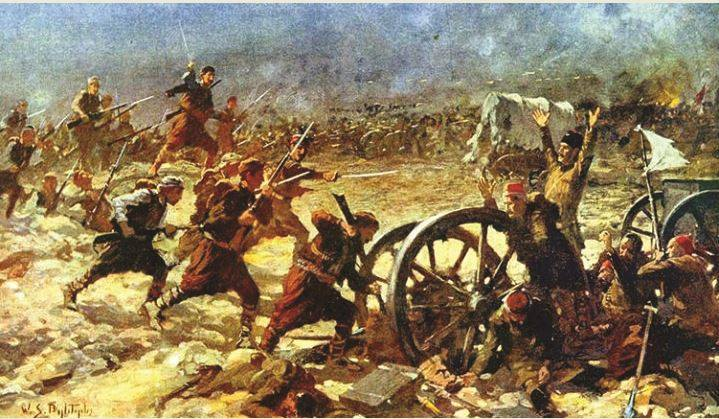

Balkan Wars and the Sanctification of History

From the Balkan Wars of the early 20th century to the conflicts of the 1990s, the pattern remained the same: history is mythologized, religion is politicized, and symbols become calls to war. In Bosnia, religious identities became front lines. In Kosovo, historical and religious symbolism justified ethnic cleansing. In Croatia and Serbia, flags and anthems preceded bloodshed. In North Macedonia, ethnic symbols paralyzed the state. The Balkans did not fight for the future—they fought over interpretations of the past.

Political Elites and the Trade of Symbols

A constant in the Balkans is the role of political elites who exploit symbols as power capital. When economic programs are missing, the flag is raised. When justice is absent, history is invoked. When perspective is lacking, the old enemy is revived.

This works because Balkan societies are emotionally educated, not critically educated. Schools produce myths, not analysis. History textbooks create pure heroes and absolute enemies, not complex realities. Thus, the symbol becomes a closed circuit: fear produces loyalty, loyalty produces power.

The Balkans as a Permanent Ideological Periphery

The region rarely produces original political ideas. Instead, it imports ideologies, religions, and state models, mixing them with local trauma. The result is dangerous hybrids: religious nationalism, ethnic socialism, formal democracy with clan mentality. Here, symbols do not evolve; they recycle pain.

Symbol as Counter-Identity: “We” Exist Because “They” Exist

Many Balkan symbols were not born from philosophy or vision, but from differentiation:

- The cross against the crescent

- Language sanctified against another language

- The hero raised against the “historical enemy”

This created a reactive identity. Not “Who are we?” but “Whom do we hate?” Without enemies, symbols lose meaning. That is why peace is difficult in the Balkans—peace threatens the symbols.

The Balkan Hero: From Historical Figure to Political Totem

Heroes are rarely treated as complex human beings. They become untouchable totems. Once hero worship begins, analysis ends.

Heroes serve three functions:

- Justifying past violence

- Excusing present failures

- Mobilizing future conflict

History becomes an arsenal, not a lesson.

Religion as Foreign and Domestic Policy

Religion became a geopolitical tool:

- Orthodoxy aligned with Russian and Greek interests

- Catholicism with the West

- Islam with the Ottoman legacy and modern global actors

Belief was replaced by strategic alignment. Wars with “religious colors” were political wars speaking God’s language—a dangerous language that rejects compromise.

School Textbooks and the Production of Hatred

Education in the Balkans builds selective memory, not critical citizenship. Textbooks:

- Emphasize “our” suffering

- Minimize “our” crimes

- Demonize the other

- Mythologize history

Hatred is cultivated slowly and activated in crisis.

Balkan Politics: Managing Fear Through Symbols

When citizens demand accountability, politicians redirect attention to identity, flags, and external threats. Symbols are always ready to wave when reality fails. They delay solutions and protect elites.

The Balkans’ Pathological Relationship with History

Unlike Western Europe, which used history to build institutions, the Balkans turned history into identity. The past rules the present.

People feel both proud and victimized—proud of a mythologized past, victims of a failing present.

Can the Balkans Be Freed from Symbols Without Losing Identity?

The real question is not how symbols were built, but why they still dominate. The region is not blocked by lack of resources, but by symbolic overload. Identity has become obsession, history dogma, religion territory, and politics emotional manipulation.

Demythologization Is Not Erasing History

A symbol-only identity is fragile. Societies that cannot critique their symbols:

- Do not learn from mistakes

- Lack empathy

- Fail to build justice

Contextualizing suffering is not denial—it is maturity.

Real Reconciliation or Frozen Coexistence?

The Balkans speak of reconciliation but practice frozen coexistence. Symbols keep wounds open because wounds mobilize people.

True reconciliation requires:

- Mutual recognition of crimes

- Demythologizing heroes

- Educational reform

- Clear separation of religion and state

Citizenship as the Antidote

The solution is not new symbols, but stronger citizenship:

- Equality before the law

- Strong institutions

- Critical education

- Public ethics

The Balkans and the Fear of Normality

Normality requires institutions, not heroes. Stability weakens symbols, so crisis is often preferred.

From Symbolic Balkans to Ethical Balkans

The Balkans do not need louder identities, but stronger ethics.

A symbol that does not serve life becomes a justification for death.

History not retold honestly repeats as tragedy.

Religion used as a weapon loses its soul.

The Balkans will move forward not with bigger flags, but with greater responsibility.

This is not optimism—it is a moral choice.

References

- Maria Todorova – Imagining the Balkans

- Eric Hobsbawm & Terence Ranger – The Invention of Tradition

- Benedict Anderson – Imagined Communities

- Tony Judt – Postwar

- Hannah Arendt – Between Past and Future

- Mark Mazower – The Balkans

- Rogers Brubaker – Ethnicity without Groups

- Miroslav Hroch – Social Preconditions of National Revival in Europe