Zhanicë is a settlement in the Municipality of Plav in Montenegro.

Abstract

This document provides a detailed historical, geographical, and toponymical record of the Albanian settlements of Zhanicë, Pepaj, and Nokshiq. It traces land ownership, village structures, fields, pastures, hills, roads, water sources, and cemeteries, while documenting the population’s experiences through centuries of conflict, displacement, and resistance. The text highlights the effects of Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, Montenegrin, and Yugoslav pressures on these communities, including forced migrations, massacres, and the preservation of local Albanian culture. Oral histories, informant testimonies, and local knowledge are used to maintain the villages’ heritage despite diaspora and historical upheavals.

Geography

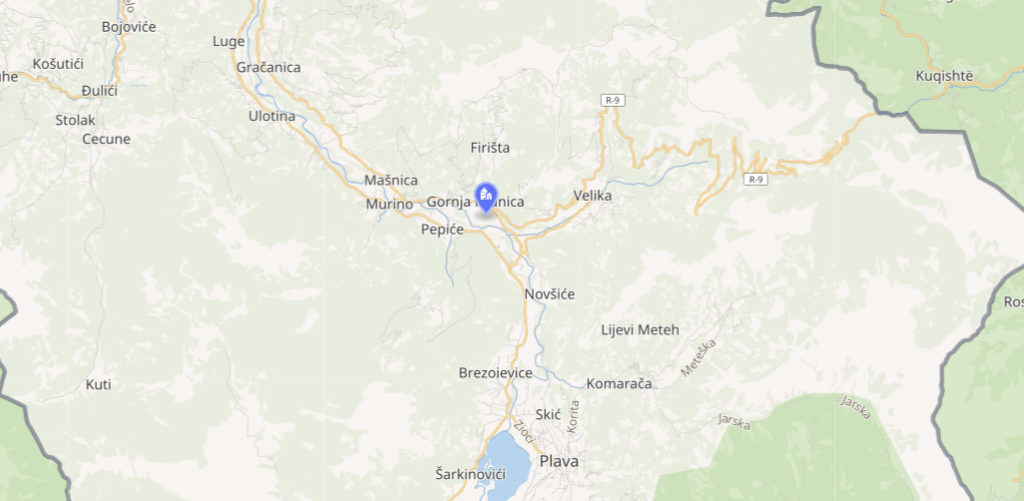

Zhanicë lies on the right bank of the Lim River, which originates from Lake Plav and flows through the valley, leaving the village of Pepaj on its left. Both villages are located between Plav, the municipal center seven kilometers away, and Murinë, the administrative center three to four kilometers away.

To the east it borders the Montenegrin village of Velika and a range of hills and peaks, including Sekirica and Shejtan Tepe. This valley, where these villages gravitate, was always an inseparable part of the resistance of Guci until 1954, after which Plav became the municipal center. It is therefore not surprising to read the words of the Russian travel writer A. Boshmakov, who wrote that Guci is the heart of Albania.

Zhanicë has an older origin than Pepaj. Under the name Rzhanicë, it appears in the Defter of the Sanjak of Shkodra as early as 1485, when it had 92 households, five bachelors, two widows, and three mills. The importance of this village as an inhabited crossroads can be seen when compared to Guci, which at the time had 121 households and three mills, while the village of Nokshiq had only 23 households. Since Pepaj does not appear in this register, it is assumed that it was considered an inseparable part of the Upper Lim Valley, which had 80 households and two mills and was later often attached administratively to Murinë.

Toponymy and origin of the name

The origin and formation of the toponym Zhanicë are difficult to determine. Although it is mentioned very early, over the course of history and continuous invasions it underwent changes, like many other place names in the region, through shortening, deformation, or replacement. As a starting point, local descendants believe the place was once associated with the name Nikë Fara.

Based on the village’s current position, informants from the area suggest that it was formed by landslides or avalanches. This reasoning has some logic, as the village is surrounded on three sides by slopes descending toward the Lim River. Areas formed by collapses are locally called zharginë, for example Zharget e Nikës. From this perspective, the name may derive from the combination of zhar and Nikë or Nicë. The presence of the sound r complicates pronunciation, and many locals omit it, emphasizing Zhanicë, which they consider more credible.

These interpretations suggest that Zhanicë was formed as a result of soil sliding. Even today, expressions using zharg are common in the local language to describe dragging or sliding movements caused by avalanches. The variant Azhanicë is also encountered. Another interpretation links the name to the diminutive form of Nikë, with Nika becoming Nica, a pattern found in many settlements in the Plav and Guci regions.

Similar affectionate or diminutive forms are common in Albanian-speaking areas, such as Babush, Bakë, Nanëloke, Nanë-cicë, Hysko, and Hasko. Comparable naming patterns are found in other Albanian regions as well, such as in the Bjeshkët e Burimit in Kosovo, where the toponym Korenik combines the words kore and Nikë.

Based on the conviction and preference of informants originating from this village, the form Zhanicë is used.

Anthroponyms and family names

When analyzing local toponyms and anthroponyms, attention must also be paid to the patronyms Novaj and Novović, which are still present in Zhanicë. Both Muslim and Orthodox families bear these surnames, raising questions about their deeper origin. Many believe the lineage originates from the Berisha tribe, as their ancestor was named Nue Berisha, possibly also known as Nikë Berisha. These names are linked to older Albanian forms such as Ndue, Nue, Nou, Noci, with Nueci being particularly common in the region.

The name Ndue is thought to derive from Andue, with the initial A and final N dropped over time. This is reflected in the testimony of Hajrie Nuecaj Mehaj, born in 1985 and aged ninety, who recalls that villagers referred to her family as Nuecaj. Variants such as Nuajajt, Nocajt, and later Novović appeared, especially after 1919.

Similar testimony is given by Fazë Balidemaj, who spent seventy-five years married into the Nuecaj family, recalling expressions such as marrying into the Nuecaj family or visiting them during Bajram. Toponyms such as Jazi i Nout and Lugu i Ocit further support the historical presence of this lineage.

After 1912 and 1913, throughout the Plav and Guci region, Montenegrin authorities often changed Albanian names, religions, and surnames by adding or removing sounds, which obscured their original roots. Nueci, Noci, or Ndue could easily be transformed into Novo. Some Nuecaj families state that their earliest ancestor was named Lazri, a name that could easily merge with Lazar, linking different lineages.

Agriculture and feudal rent

Zhanicë belonged to the Plav vilayet within the Sanjak of Shkodra and was subject to the Ottoman timar system. At the end of the fifteenth century, villagers cultivated agricultural products and paid dues, with each household contributing specific quantities.

They produced wheat, rye, oats, and barley. Later, the tax system shifted to monetary payments, with each household paying the equivalent of one ducat. According to the Montenegrin Kanunama of 1523, the payment of fifty-five florins covered three main obligations, including the harac tax.

Villagers also paid dues for mills, water, bachelors, mountain pastures, and household chimneys. These data show the heavy exploitation imposed on villages by various authorities.

Today, most traditional grains are no longer cultivated in the area except for maize, as modern hybrid seeds do not adapt well to the climate. Beans and potatoes are known for their high quality. Among fruit trees, apples and plums are most resistant, with plums used to produce high-quality rakia, as well as pekmez and other sweets.

Livestock breeding was important due to suitable pastures. Sheep of the syka breed and goats adapted to long winters were raised, as well as small, sturdy cows. From milk, villagers produced cheese, butter, yogurt, whey, and curd.

Hydrography and landscape

The Plav and Guci region lies in a valley surrounded by peaks and cliffs of the Albanian Alps, with heavy snowfall. It is enriched by numerous watercourses, beginning with springs in Vuthaj and flowing into Lake Plav. From the lake, the Lim River continues, passing villages such as Nokshiq, Velika, Zhanicë, and Pepaj, then flowing through Murinë and winding through the Lower Lim Valley.

Demography

The population of the region consists of clans such as Kelmend, Triepsh, Shalë, Berisha, Gash, Krasniqi, Hot, Grudë, Shkrel, and Vasojević. These populations are spread across the region and centered around Guci and Plav. Many settlements are recorded in the Defter of the Sanjak of Shkodra from 1485.

Montenegrin scholars have acknowledged that many clans and surnames in the area are of Albanian origin and that Albanian was once the majority language. Political developments after 1948 influenced ethnic self-identification. Many Muslims adopted the Montenegrin language and registered as Montenegrins, later identifying as Muslims by nationality, and after 1991 as Bosniaks.

Census data show fluctuations in ethnic identification from 1948 to 1991. The 1981 census recorded in Zhanicë a majority of Montenegrins, a small number of Albanians, and very few Muslims. According to the 2003 census, expressed in percentages, the population consisted mainly of Bosniaks, followed by Albanians, Serbs, Montenegrins, and a small number of Catholics.

According to these records, it can be understood that the Albanian language is spoken, to a greater or lesser extent, across a wide part of these regions. Unfortunately, since 1980, with the death of Ujkan Coli “Vllaka” in Nokshiq, a place of Albanian pain and pride, Albanian now breathes only through graves, memory, and longing.

The spoken use of Albanian is currently most reduced in the villages of Zhanicë and Pepaj, where there are very few Albanians. In Nokshiq it has completely disappeared.

Albanian inhabitants of the Plav and Guci region call themselves highlanders. Proud of their past, they often say: “The highlander is not brought forth by his mother, but by the rifle from the chest.”

Dialectal affiliation

The dialect spoken in this area belongs to the northwestern Gheg dialect, specifically to the northern subdialect of Malësia e Madhe, with some partial similarities to the northeastern Gheg dialects of the northern subdialect.

Oral tradition

The remarkable preservation of the Albanian language enriched and strengthened Albanian folklore in this region. As a result, heroic songs of the legendary epic tradition dominate, accompanied by instruments such as the lahuta, çifteli, flute, and tepsi.

Clothing

Men’s traditional clothing largely corresponds to that of Malësia e Madhe, as an inherited cultural trait. Meanwhile, the authenticity of women’s traditional dress gradually faded. This occurred due to historical developments and frequent contact with other regions. Trade also played a role, introducing new models and artistic tools that highland women began to incorporate into their handicrafts. With the arrival of woven fabric, the woolen xhubleta was transformed into women’s shirts. Decorative patterns were embroidered onto fabric, but each change contributed to the loss of original authenticity, as wool thread and its products were abandoned.

Girls attempted to preserve traditional dress, but they could not save it from the passage of time. Until the 1950s, Muslim highland girls prepared the “virgin xhubleta,” white as in earlier times, symbolizing virginity. However, they narrowed the bell-shaped hem and decorated it with spike embroidery at the bottom and around the neckline. Faithful preservation can still be observed during Catholic holidays at church services or weddings in villages such as Kaganik in Guci, Vishnjevë, and formerly in one family in Pepaj. Even this “virgin xhubleta” underwent changes, with decorations added across the black field using white wool or cloth bands from the hem to the waist.

Among Muslim girls, until the 1960s, the “virgin xhubleta” without the bell-shaped rim was worn, resembling more a fabric dress. The difference was that it was made of wool thread, skillfully woven on the loom. Around the hem, which reached below the knee, black spike embroidery with triangular amulets was arranged, and similar but narrower decorations were added around the collar. With this narrowing, original authenticity was lost.

Women’s xhubleta in antiquity

This term refers to the red xhubleta worn by brides and the black xhubleta worn by elderly women. Their bell-shaped form stood out for craftsmanship and color. This type of dress closely resembled that of Malësia e Madhe and Dukagjin. When these villages were predominantly Albanian, women’s clothing did not differ from that of Muslim Albanian women in other villages of the region. Over time, it transformed into various fabric garments, gradually losing its original character in the name of perceived modernization.

The occupier and religion

Like every occupier, the Ottomans used relatively mild methods to change religion. The pride of the highlanders, transformed into resistance, led to organized opposition through bands of fighters. As a result, the conversion from Catholicism to Islam progressed slowly. Parts of the Lim Valley that accepted Islam and adopted the titles of aga and beg later experienced conversion to Slavic Orthodoxy. By the second half of the eighteenth century, about twenty-five family groups had accepted Islam, and a century later they were forced to convert to Slavic Orthodoxy. After 1826, the process of conversion to Orthodoxy intensified.

The most active role in converting Muslims to Orthodoxy was taken by the vojvoda of Matishevë, Milan Vuku, appointed by the Sanjakbey of Shkodra. Under the direction of Cetinje, he descended into the Lim Valley with the task of changing the religion, names, and surnames of locals to Slavic ones. This was done publicly, often by the vojvoda or an Orthodox priest, who then declared himself their godfather. According to a travel account, in the village of Rzhanicë alone, 250 people were converted.

According to informants, the villages originally had a Catholic church in Brezare (Brezovicë), where a Slavic Orthodox church was later built.

With the arrival of the Ottomans, the construction of mosques also began, initially in military posts, such as Xhami Turija on the hill of Nokshiq and the Nizam Mosque near Pepaj, where the place name Qafa e Xhamisë is still preserved.

By the end of the eighteenth century, conversion to Islam had been completed. Subsequently, mosques were built in settlements. Around 1830, a mosque was built in Nokshiq, which was burned by Montenegrins in 1912 and rebuilt by locals in 1939. Its imams were Mulla Halil Banderi and Smajl Mekuli. Its existence was short-lived, as it was burned again in 1941. Depopulation followed, and with the death of “Vllaka,” the last Albanian in the village in 1980, memory itself seemed sealed. The mosque in Zhanicë, built in 1939 with villagers’ contributions, existed until 1944, after which only its foundations remained.

Historical conflicts

Events after 1820 were linked to Russian ambitions to control the entire Lim Valley. After prolonged conflicts, Cetinje intervened more seriously, sending Iguman Zečević, who introduced the “Law of the Vasojevićs with twelve points,” initiating a gradual conversion to Orthodoxy over three decades.

Permanent settlement of colonists in the Lower Lim Valley began with increasing violence against the indigenous population. Armed bands, directed by Cetinje and supported by Tsarist Russia, operated freely in the region.

These circumstances led to the war of 1854, when Cetinje’s forces attacked the kaza of Guci. Local leaders, supported and later led by Ali Beg of Guci, organized volunteer forces and set ambushes near the Previs Pass and Sutjeska. This battle inspired epic songs later immortalized by Gjergj Fishta.

In January 1854, Montenegrin regular forces faced Albanian volunteers, poorly armed but united and determined to defend their ancestral lands. The Albanians emerged victorious, inflicting heavy losses. Montenegrin memoirs acknowledge this defeat as unprecedented in the region.

Montenegrin scholar Veshoviq also noted that their forces did not understand Ali Beg’s tactics, and among the local population, the “white army” was remembered with fear.

French diplomat Ekar wrote that 105 heads were cut and blamed Russian agents for instigating the war. The Austrian vice-consul in Shkodra reported 136 killed in the Lim field and six drowned in the river. Russian officer Kovalevsky later wrote that the goal was to exploit the Lim Valley for “Old Serbia.” Russian journalist P. A. Rovinsky later documented proclamations calling for expansion into Albanian lands.

According to the memoirs of Gavro Vuku, at least one third of the nahiye was brought under Montenegrin control, and after defeat, eighty Orthodox heads were publicly displayed in Guci.

After these failed battles, Vasojević groups activated armed bands led by the church of Gjurgjevi Stupovi, under Iguman Zečević, launching repeated attacks on the population centered around Guci.

Toponymy and anthroponymy of Vasoviq

The toponym and anthroponym Vasoviq is relatively late, appearing sometime after the dispersal of the Kelmendi tribe by Hydaverdi Pasha. The interconnected history of the inhabitants of these regions is also confirmed by many Montenegrin authors themselves, such as Dr. Dašić and Marko Miljanov, who place this sequence of names within the line of tribes: Ozri, Pipri, Hoti, Krasi, Vasi, Bakeqi, Kelmendi, Kuçi, and others. According to them, it follows that in these areas cousins fought among themselves, for example the descendants of Vasi, the Vasojevićs, and those of Krasi, the Krasniqes.

In conversations I had between 1975 and 1980 with several inhabitants of the village of Velika, of Orthodox faith and Montenegrin nationality, which borders Zhanicë, Nokshiq, Meteh, and Rugova, they did not hesitate to state the truth that they originate from Albanians, from tribes such as Gash, Shalë, Kelmend, Berisha, and Kastrati. From this analysis it emerges that the entire present-day Vasojević region has Illyrian Albanian origins. However, under current conditions, the majority deny what they once openly acknowledged.

These data and other notes indicate that the Vasojevićs managed to establish themselves in these areas after the eighteenth century, descending from regions such as Kuç, Kelmend, Lijeva Rijeka, and others, that is, from the Pashalik of Shkodra. This is confirmed by Gavro Vuku, son of the Vasojević standard-bearer, in his memoirs. He states that his father received the title of Bajraktar from the Sanjakbey of Shkodra, a title that the Vladika of Cetinje would not recognize unless he first brought the head of a well-known warrior from the kaza of Guci.

After Milan Vuku fulfilled this condition, Cetinje granted him the title of Vojvoda as well. From that moment on, this leader of the Vasojevićs held two titles of authority, one from each center. Through such actions he disrupted relations with the kaza of Guci.

With these titles he later assisted the iguman in converting the population to Slavic Orthodoxy. From then on, frontal clashes followed, battle after battle, bringing constant disturbances as conflicts spread through the villages of the Lim Valley, aimed at conquering the regions of Plav and Guci.

Political pressures and local resistance

After the battle in Murinë, the Vasojevićs requested from Prince Danilo that this region be annexed to Cetinje, since relations with Guci had become extremely strained and such consent might have been accepted. The policy of Cetinje never abandoned its claims to the lands of this valley. Even in 1859, Cetinje unilaterally established three captaincies in the Lim Valley. Gjol Llaban was appointed as the first captain. The captaincy of Velika, led by Milet Paunović, was often used as a source of provocation. Zhanicë lay between Murinë and Velika. Here too they attempted to organize a captaincy, appointing Tahir Shabani of Zhanicë as its head.

Tahir Shabani did not accept such a position, nor did the local population. After these wars and plans, this crossroads lost its importance, as travel through the Lim Valley toward Pešter, Novi Pazar, Bijelo Polje, and other areas was interrupted. This dealt a severe blow to the traders and livestock breeders of the Guci region.

These actions and the continuous, unbearable attacks by Vasojević armed bands along the border with the Guci region inspired Guci to form the Committee for the Salvation of the Population, based in Guci, in which these villages were also represented.

The suffering of the Plav and Guci region

The Albanian population strongly expressed dissatisfaction with centuries of oppression in various forms, including the nationwide movement of 1878 to 1880. This is also evidenced by the words of Ali Pasha of Guci, spoken to Maxhar Pasha in Gjakova, when he organized an ambush to block Mehmet Pasha’s passage: “What are you doing here, whom did you ask that you are handing these lands over to our enemies, are you giving away your own lands?”

The pan-Slavic plans of Tsarist Russia to divide Albanian lands among its allies were evident. This expansionist policy surfaced at the beginning of the Eastern Crisis, exploiting the exhaustion of the Ottoman Empire in defending its territories. With the Treaty of San Stefano on 3 March 1878, the Ottoman Empire was left with little more than words, declaring that Albania was its exclusive possession and under its administration. These illusions of power then passed through the Congress of Berlin, where distorted decisions were taken to divide Albanian lands. Others were rewarded with Albanian territory.

Such actions inspired the folk poet to protest in verse, accusing the kings of dishonor for giving away чуж land. These circumstances became the main reason for the Albanian people to unite against the partition of their ancestral lands. Under these conditions, the region of Plav and Guci became the first “gift” to the neighboring aggressor, a bargaining chip in the hands of enemies.

Seeing Albanian determination, the folk poet sang that Plav and Guci would not be surrendered, young and old alike ready to sacrifice themselves. It was therefore no surprise that at the very beginning of the organization of the League of Prizren stood a son of these lands, Ali Pasha of Guci, as also described by Gjergj Fishta.

Defense of the homeland

Bravery granted by God and geographical position became a shield for other Albanian regions. Zhanicë, Pepaj, Nokshiq, Meteh, Martinaj, Gërncar, Vermosh, Rugova, and all of Plav and Guci were destined to become bases of the first battles and later of the wars conducted in accordance with the decisions of the Albanian League of Prizren.

Among all the battles of this period, special importance is given to the one in the village of Nokshiq on 4 December 1879. Thanks to sacrifice, courage, and determination, this battle ended in a great victory. The villages of this valley suffered the most, as the fighting took place there, while warriors from other Albanian regions remained loyal, having set ambushes on all sides to defend these Albanian hearths.

With pride, the anonymous folk poet expressed their determination in verses declaring that neither the Turk nor Moscow would rule them, for they were fighting for their own land. For the defense of these lands, all Albanian regions responded to the call for help. Thus, it can rightly be said that the wars for the defense of Plav and Guci began in this Lim Valley, with trenches in these villages, culminating in the decisive victory of 13 January 1880 as a symbol of resistance in defense of the homeland.

Because collective memory was faithfully preserved, events remained vivid. Therefore, hostile writings and reports by non-Albanian authors did not mislead honest people, as the truth remained clear that Plav and Guci were defended by their inhabitants and their compatriots. This memory has been cultivated honorably, in writing and orally, through songs and through the works of Gjergj Fishta, who dedicated a significant part of his masterpiece The Highland Lute to these hearths, which were brutally attacked by forces led from Cetinje, supported by Tsarist Russia and other European powers.

When the poet spoke these verses, he certainly had in mind the stoicism of the strategist Ali Pasha of Gucia, as well as the confidence he placed in his volunteer forces:

“With Albanians, O Nikola,

A man may find himself in great hardship

If he does not approach them as a friend,

For they are made of steel.

Whether on land or on sea one dares to touch them,

Be it a Prince or be it a King,

They are kings upon their own soil—

Greatly mistaken is he who provokes them!”

The brave men of these regions also took part in the battle against Mehmet Pasha Paxharri, who was killed in Gjakova. Children played with his severed head in the alleys of Gjakova. The presence of the warriors from these regions is also attested by Gjergj Fishta, who wrote:

“For the leaders of Albania,

Together with Ali Pasha of Gucia,

Had sworn a great oath,

Young and old alike, to fall in battle.”

Further emphasizing the grandeur of the general call to arms, he adds:

“Send forth the call among Tosks and Ghegs;

Gather together like seeds in a pomegranate…

Shame and disgrace upon the Albanian tribe

If the honor of the ancestors is betrayed.”

Such a call drives the warriors to spare neither life nor death, while still respecting the adversary:

“They no longer look upon life or death,

The brave press forward, charging shoulder to shoulder…”

Even the anonymous folk poet composed numerous epic verses celebrating heroism and valor, granting deserved epithets to the warriors of Zhanica, Pepaj, and Nokshiq:

“Oh, what falcons the Highlands possessed—

All of humanity did not have their equal…

The sons of Pepaj and Zhanica

Sacrifice themselves for the homeland;

They were known in Lodër and even in Berlin…”

With such a spirit also resound the verses of the song “The Call of Gucia”:

“That call of Gucia

United twelve thousand warriors

To guard this Albanian land.

O hills, why do you tremble?

The call summoned you as well,

To Kërshllahe, where the brave are known,

Where word and oath prevail,

Honor and faith of this land.

From the rock emerged the mountain men:

Hoti, Marënaj, and the men of Gucia,

Nokshiq, Pepaj, and Zhanica,

Together with the people of Plava, lying in ambush…

The warriors of Nokshiq fight

As if born to die for the homeland…

Avdyl Pepa—God granted him

To fight like the ancient epic heroes.”

The border imposed by force

The Great European Powers completed the demarcation of the border without taking into account the reality on the ground or the wishes of the local population. With this border line, a policy of continuous and long-lasting conflicts and confrontations emerged—conflicts that still simmer today—because the Lim Valley was divided into two districts: that of Gucia and that of Berane. From that time onward, Murina, together with the surrounding villages that formed the Upper Lim Valley, remained under the jurisdiction of Gucia.

In those days, the verses of the folk poet were sung with great force in these regions:

“By the soul of my tender mother,

I am the blood of this land…”

Those who composed and sang such verses have died, and those who were meant to inherit them have also departed.

“I carry Albania with me; no king or ruler can take it. With this handful of Albania, I defend the land from seven kings.”

Although Cetinje signed a peace agreement regarding this border, it soon began supporting the village of Velika, which had adopted the Slavo-Orthodox faith and Montenegrin nationality. Velika, bordering the Albanian villages of Zhanicë, Pepaj, Nokshiq, Meteh, and the Rugova region, became a source of tension. This political maneuver quickly escalated when Velika received weapons from Cetinje and Russia, provoking clashes with neighboring Albanian villages and eventually triggering a broader conflict.

Assistance to the Velika villagers also came from the Vasojeviq and other Montenegrin regions. This strategy increased attacks and forced Velika to accept separation from the Gucia center, which in turn led to hostile confrontations with neighboring villages. The erosion of traditional customs escalated into severe human rights violations, including the burning of the Pepaj mosque, the execution of Mulla Osman Celë of Zhanicës, and the murder of Kune Drejaj, a young girl from Pepaj. During this period, four girls from Zhanicë were captured, mutilated, and abandoned, illustrating the extreme brutality of the conflict.

Princ Danilo, with the support of the Shkodra vali and Abdi Pasha, implemented his political agents in the Lim region. From 1858 onward, he operated through appointed captains in the area. European forces and Tsarist Russia joined in to weaken the Ottoman Empire. In this process, Russian intervention led to the appropriation of Albanian lands, granting them to Cetinje as a reward, especially after the infamous Berlin Congress. Albanian territories thus became a bargaining chip among European powers.

Zhanicë, a key crossroads for the delivery of territories to Cetinje, became one of the first sites of assault in the campaign to conquer Plavë and Gucia. Throughout these confrontations, the men of Zhanicë, Nokshiq, and Pepaj fought valiantly alongside volunteers from across Albania. Following the principles of the Albanian League of Prizren, a general mobilization was issued, spanning ages seven to seventy, under the command of Ali Pashë Gucia. From the Gucia center of Kërshllahet, the entire defense effort was coordinated. More than 4,000 armed volunteers from various Albanian regions joined over 8,000 local civilian fighters to resist the regular forces of Cetinje, ultimately achieving victory.

The autumn battles of 1879, fought relentlessly, culminated in a major victory in January 1880. The capture of two Russian flags in Murinë exemplifies both the foreign involvement and the determination of Albanian fighters. Such mass participation reinforces the view that the defense was a collective, national effort.

Despite the hardships, the region of Plavë and Gucia remained a target of external pressures, exacerbated by Russian-Slavic politics and local family rivalries. Ottoman and Montenegrin authorities exploited religious and ethnic divisions to maintain control. Yet, Albanian warriors were prepared to fight to the death, guided by the principle that “a brave man is not bound.” Long hair was kept as a practical measure for head-to-head combat, allowing space for maneuver or defense in case of execution or decapitation.

During fieldwork between 1970 and 1978, the author documented the surviving communities, including those who had adopted Montenegrin, Serbian, or Bosniak identities. These villagers preserved the memory of heroism and sacrifice, ensuring that the blood spilled to defend Albanian homelands continues to illuminate history.

The courage of the people from Zhanicë, Pepaj, Nokshiq, and surrounding villages is recorded here, based on careful observation and firsthand accounts. While not exhaustive, these notes highlight the continuity of Albanian resistance and the enduring significance of local defense efforts.

I apologize to those for whom I have no records or testimonies, yet who endured suffering and shed their blood. They remain in our hearts and in the collective national consciousness. It is my hope that in the future, these records will be supplemented—either by myself or by other scholars—for the period between 1879 and 1945. We owe them this, for they defended their ancestral lands.

From Zhanicë: Gjekaj neighborhood: Ramë Shabani with his brother Arif; Kurt Mirashi with two sons; Kolë Gjeka with sons Zhuji and Muji; Tafil Isufi with his brother Myftar. Shabaj neighborhood: Asllan Shabani with brothers Misini and Halili, with sons Ramen and Idriz; Ali Uka; Daut Misini; Muzli Çela with two sons, his wife, and his brother Demë. Gjelaj neighborhood: Ujkan Daka with brother Bajram; Asllan Cena; Mirash Hasani with wife and son; Xhemë Ujka; Bajram Osmani. Nuecaj neighborhood: Kurt Nueci; Asllan Gjeloshi with brothers Kurt and Ajdin; Muj Spahija with daughter and brother Loci; Sejdi Syla; Bajram Syla with son Ali. Shalunaj neighborhood: Sokol Elezi; Nuradin Asllani with wife and son; Sylë and Ramë Shabani. Lukaj neighborhood: Ramadan Ferizi; Ramë Kurti with brother Feriz; Kurt Mustafa with two sons; Ukë Halili; Pjetër Loshi. Barku Lukaj: Arif and Tafil Ujka; Pjetër Loshi. Celaj neighborhood: Kurt Mustafa; Ukë Halili; Abaz Feku.

From Pepaj village: Drejaj neighborhood: Ali Smajli with brother Miku; Gjergj Elez Alia. Bacaj neighborhood: Avdyl Baci with brother Ukë; Mie Isufi with sons Hasan and Kurt, and brother Jahë; sons of Rrustem Baci: Harediri, Avdyli, and Galani. Lekaj neighborhood: Ukë Kola with brothers Gjon and Dren. Nikaj neighborhood: Pjetër Nika with sons Ukë and Lazri.

From Nokshiqi: Bufaj neighborhood: Kurt Asllani; Sylë, Ali, Deli, Sokol te Maliqit; Sokol Sejdiu; Brahim Shabani; Brahim Jakupi; Smajl Ibra; Groshi with son Deliun. Mehaj neighborhood: Nuro Kurti with brother Zenel; Adem Neziri with son Avdyl; Sali Murseli; Iber Elezi with sons Ahmet and Mehin; Sali Mehi. Mekuli neighborhood: Beqir Smajli with brothers Alinë, Adem, and Hasan; Rama with brother Hysen. Selimaj neighborhood: Isuf Selimi; Ramë Bardhi; Sadik Selimi; Zhuj Sadiku.

The repeated conflicts, spanning from 1854 to the 1880s, accompanied by torture and oppression, forced this organized population to participate in Albanian uprisings against Shemsi Pasha. Many local youths were arrested, including Mulla Jaha of Plavë and Sadik Halili of Zhanicë. They also distinguished themselves in the resistance against Xhafer Tajar.

The militias of these villages operated according to programs devised by local leadership, sanctioned by the Committee for the Protection of Kosovo in Shkodër, and approved by the subcommittee in Gucia. The local population initially welcomed the “Young Turks,” hoping for reforms, but instead faced increased oppression and the confiscation of weapons. The period from 1908 to 1912 marked a time of arming for the highlanders of these regions.

Such arming facilitated attacks by the Cetinje-led military forces, which carried out particularly tragic assaults against unarmed civilians. Villages often comprised multiple families, yet the authority of the local leader (bajraktar) was respected. The residents of Zhanicë, Pepaj, and Nokshiq, despite belonging to different clans, united under the call of the bajraktar Gjekë Martini, seated in Zhanicë.

Despite repeated attacks, poverty, and isolation in mountainous terrain, the villagers endured only two seasons in a year, divided by survival duties. Additional pressures came from Slavic chauvinist policies, which intensified their suffering through various tortures, prompting them to voice their grievances more forcefully. The men of these villages joined widespread Albanian uprisings. Unfortunately, attacks by Montenegrin outlaws persisted. The villagers lived in the hope that one day the violence of Cetinje would cease and that justice would prevail.

Days of devastation

Tragically, Montenegrins violated every principle and continued relentless assaults. By the end of autumn 1912, the period marked both an end and a continuation of suffering: the end of one form of misery and the onset of worse, including ongoing violence and genocide against these areas. The aim was the eradication of the Albanian language and expression, and the suppression of descendants of the Albanian nation. Volunteer forces defending the region pursued Ottoman soldiers.

Meanwhile, Cetinje launched another offensive against the Albanian volunteer forces defending their communities. In response, attacks were carried out across these territories. Observing the imminent danger, the local leadership issued a general mobilization, which was answered by many other Albanian regions. The frontline stretched over forty kilometers, with defenders positioned in the highlands and limited lowlands to protect the ethnic territories.

The fighting was intense and fought hand-to-hand. Within one week of conflict, approximately 1,000 combatants were brought to Gucia, with more than 300 wounded. Due to the absence of precise records on enemy losses, it is impossible to provide accurate figures. The local population, in such conditions, was unable to withstand the attacks of a regular, armed, and experienced army. The first lines of resistance were manned by the men of these villages, who faced both the initial fire and the most brutal forms of violence and genocide.

As reported by the newspaper Glas Crnogorac on 11 October 1912, “The Montenegrin army captured the two centers, Plavë and Guci…” This statement implies that the march occurred after the burning of the surrounding villages and the massacre of non-Slavic villagers, whose routes led to Plavë and Guci. Events during the autumn of 1912, particularly in the early months of 1913, were profoundly tragic. The Montenegrin army, led by commanders such as Veshoviq and Avro Çemi, perpetrated the most horrific acts of genocide in the region.

At Qafë – Rrafsh of Previsë, near these villages, 700 individuals were executed, including women and children. Even the lighter executions were accompanied by extreme brutality. One witness recalled, “They killed two boys before their mother’s eyes, placed the barrel of the gun to her face, and said: ‘This powder will shoot through your sons’ hearts and out the other side.’” To preserve the memory of this atrocity, an anonymous poet composed the following verses:

“Avro Çemi, one black hand,

Gathered Plavë, gathered Guci,

Gathered Vuthaj, 200 houses,

Martnoviq, 60 homes,

Zhanicë, Pepaj, and Nokshiq,

All on the border…”

The site of execution was also precisely recorded:

“At Qafë of Previsë, when they came,

They dug the graves to bury them.

A mother’s son suffered,

Were these graves made by the father?

No, they were made for battle,

They were trenches for war.

They were struck down by battalions,

Not one survived among the seven families.”

Cetinje’s political objectives extended beyond mere territorial control; the aim was also cultural assimilation, motivated in part by the region’s natural wealth. The harrowing events deeply traumatized freedom-loving individuals. Expressing his despair, Ismail Qemali gave an interview to the Italian newspaper 11 Giornale D’Italia on 12 April 1913, stating:

“How could it occur to King Nikola to force Albanian Muslims to change their religion at gunpoint? Does he consider the bloody confrontations that will ensue?”

To survive, the men retreated to the mountains, so that the peaks of this mountain crown were never without sentries and watchmen. The population of these areas remained loyal to their homeland, continuously engaged in the Albanian movement for spiritual and national freedom. The hardships endured by these communities are remembered by succeeding generations:

“From the beginning of life, I have borne the suffering,

My parents and all the relatives!

Oh, they have always pursued and killed us,

And called it bravery, praised for this act!

Then I grew into a man, yet violence and suffering did not cease…

Now, at the end of life: again suffering, death, sorrow,

They plant destruction in our hearths,

Will our homeland ever know peace, in my soul?

The people of these regions can be seen as a steadfast and inseparable portrait, as enduring and immovable as the rocks of Malësia.

“Every handful of blood has been shed on these lands: mountains and highlands, barren plains. Thousands of highlanders were born here, on the living ridges. They grow among the pines, which give them both youth and life. They are suffering, yet noble; poor, but not base. They have strict and harsh laws, as harsh as the cliffs and as firm as the highlanders themselves. They are strong, resilient, and proud, upright and dignified.”

When we pause to analyze Malësia e Madhe, of which the regions of Plavë and Guci form a part, we are compelled to reflect on its significance.

“Its name, Malësia e Madhe, is determined not by its outward appearance, but by its inner substance. It is an Albanian region of truly remarkable repute—indeed, ‘Madhe,’ or Great. Yet Malësia e Madhe is not only great in name; it is a region defined by clear and profound virtues. In other words, ‘Malësia’ is not merely a conventional geographic or ethnographic term; it carries a rich ethical and national meaning. Though small in area, Malësia e Madhe is great in history. It is small in surface, yet vast in tradition; small in size, yet immense in virtue; small in territory, yet large in mind and heart; modest in material wealth, but extraordinarily rich in spiritual heritage.”

Why can it be said this way? Faith, generosity, hospitality, and courage—the qualities for which we take pride and have been recognized by others—appear in their purest form in Malësia e Madhe. There, a balance has always been maintained between what is spoken and what is done, between action and principle. Like the gods in ancient drama, honor oversees both the deeds and thoughts of the individual and the community.

In Malësia e Madhe, evil and falsehood were never accepted as lawful. There, authority was never allowed to humiliate dignity, nor could slavery oppress freedom. Hypocrisy could never pass for sincerity; demagoguery could not masquerade as patriotism; arrogance could not be mistaken for bravery. Madness could never ridicule reason. Whoever defended justice was valued as a friend by all. Life there was devoted to honor, justice, and truth with the same readiness with which it was given for the homeland. There, in addition to their grandeur and dignity, the highlanders would neither live nor die otherwise.

With many such statements, one can understand the reality of how deeply connected and devoted they were to these lands, to the sky above the mountains that had grown watered by sweat and blood. Through the generations, they preserved the customs taught by their mothers, sacred as heavenly plants, imbued with legendary power, which transformed into the mountain fairies, whose essence was absorbed by the warriors of these hearths, making them strong enough to confront the Black Harap from the sea and those from the Carpathians, etc.

Recalling past wrongs, they lived through the stages of history with careful vigilance because peace was lacking; thus, organizing in groups was necessary. Many young men from these regions were inspired by this principle. In the villages of Zhanicë, Nokshiq, and Pepaj, the population was always prepared, but it must be understood that circumstances did not allow the entire family to join the bands, so their ranks were not long, though brave men were among them.

The years most active for the rebel bands were 1908–1912, then 1913–1916, continuing even after 1920–1940. According to informants, large numbers of the brave men from these villages were involved in the rebel groups. Below, I present the notes of a part of them, though all were prepared to give their contribution to the homeland even unto death.

THE DECEPTIVE SHIMMER OF FREEDOM

The hope of freedom appeared with the occupation of these regions by the Austro-Hungarians (1916), because the occupier presented himself with mild behavior and gentle propaganda. In short, the highlanders of these areas were exhausted by torture and suffering. Principally, they had reached the limit of their endurance and sought relief, even from the occupier, as long as they would not be subjugated. The new occupier, according to informants, showed calmer signs and persuasive prudence. He began to grant freedoms, communication in the Albanian language, and proclaimed religious rights. In addition to the three local teachers—Sado Musaj, Hysen Vuthi, and Ismail Nikogi—he brought five teachers from Zara to develop instruction in the Albanian language. Among them was the well-known Josip Rela.

From the locals, he organized a volunteer unit (“51”), dressed and arranged militarily. Later, he trained about 700 locals to acquire basic military skills. Among these organizations, the young men of these villages were also included. Those who had fled and the outlaws returned to live in their native lands, which had been leveled and devastated.

One of the first signs of distrust toward the new occupier was when he sent 400 reservists to assist his forces on open fronts, distributing them across Montenegrin territories without the approval or knowledge of the locals. A small number were left in these areas to demonstrate that the new occupier was supposedly in service to this population. To assert his oppressive presence, once he noticed that the Albanians were beginning to revive and seek national education, he removed the local teachers and replaced them with those he brought.

The most disgraceful case was when, alongside these teachers, he brought a Bosnian “chief imam” from Bosnia, who, to close the Albanian schools, exercised terror in the name of religion. The Austro-Hungarian administration, to achieve its goal more successfully, armed the imam. In addition to a revolver, he was given a club to use against anyone who did not attend the mosque for the “five daily prayers.” He would even use the stick against a man over forty who had not shaved his beard.

This occupying force, however, met its end. By the end of 1918, it was violently expelled by volunteer highlander forces. In all these sufferings and tortures, no mercy was shown toward this region or its villages. Wherever the first gun was fired, the first victim fell. The fragile strands of freedom were never seen by the inhabitants of these villages because they clashed with the outlaw bands of Velishani and Vasojeviqs.

After the Austro-Hungarian forces departed, local leadership in Guci resumed based on local principles, customs, and the maturity of the Kanun. Every village restored calm and began to rebuild their burned homes. Unfortunately, this period was short-lived. During this time, in Kacanik of Guci, a Serbian military unit was cunningly stationed, claiming they were there to protect the population from the army of King Cetina. Since the locals had lost trust in the past, the regional leaders gave them guidance before they could demonstrate hostility and force.

According to field notes, I present the following data on the bands and outlaws. I am aware there are others, but I have no information on them.

Village Zhanicë:

- Gjekaj: Tafil Isufi, Bajram Isufi, and Shaban Tafili

- Gjekaj (Tahiraj): Arif Tahiri with sons Zhuj, Mustafa, and Xhemë. Xhemë Arifi was killed in Mokna

- Shabaj: Hasan Kurti with sons Smajli, Halili, Uka, and Shaban with son Idriz; Demë Shabani with sons Muça and Zenel; Celë Shabani with son Deli and grandson Rrustem; Sadik Halili and Vesel Halili

- Gjelaj: Brothers Osman, Mehmet, and Mujë Daka; Idriz Bajram Daka; Asllan Veseli with son Cenë. Previously, Bajram, Osman, and Mujë Daka had been killed in an ambush at Gjollat e Dakë

- Ujkaj: Demë Hasani with brother Sadrinë

- Hasanlukaj: Rexhë Asllani with brother Haradin and son Hajrudin; Kadri Murseli with son Sadri

- Closely allied with the Zhanicë men was their nephew, son of Shake Uka, sister of Idriz Uka, leader of a band, the brave Plavjan Adem Kolashinci, whom the Vasojeviqs called “crni” (the black), killed in an ambush at Lybeniq near Peja.

- Another nephew of the Gjelaj family was the well-known Ujkan Ahmeti of Nokshiq, who had his own band with his daughter Rabie.

- Also a nephew of the Shabaj family was Azem Bajraktari of the Martinaj, leader of a rebel band, later a member of the Kosovo Committee in Shkodër.

- Çelë Neziri with sons Ibish and Idriz, with nephews Sylë, Ramë Ibish, and Mujë Idriz;

- Ali Feriz Feku with sons Sokol and Ujkan; Avdi Feriz with son Rexhë and Abaz Feku

- Lekaj: Brothers Zenel and Arif Hysi, and Tafil Zeneli

- Shalunaj: Elez Sokoli with sons Alia and Ruci, and nephews Bektesh Alia and Sokol Sylë with son Cafi

- Nuecaj: Nuec Spahija with son Sylë and nephews Haxhi, Bajram, and Niman; Osman Nueci; Selim Lushi; Mustafë Muji; Avdyl Sejdia with sons Feriz and Ramë; and Nuri with son Zekë

From the village of Pepaj:

Drejaj – Deli Smajli with his son Brahim and brother Sadri; Brahim Elezi; Asllan Ujku with his son Mushak and brother Hajdar; Halil Avdia with brother Cenë.

Bacaj – Zenel Avdyli with son Istref; Sali Jaha with sons Jahë, Mustafa, and Hasan; Feriz Uka; Kei Haradini; Azem Avdyli; Gim Galani with son Galan and brother Duq.

Lekaj – Adem Kurti with sons Bacan and Prel.

Gjonaj – Mark Gjoni with son Bac.

Nikaj – Gjon Pjetri with brother Çuni, etc.

From Nokshiqi:

Buçaj – Ujkan Ahmeti, Zymer and Imer Maliqi, Elez Kaserni, Mustafë Isufi, Beqir Groshi with son Reku, Dul Kameri, Mand Dishi with sons Sekun and Celë; Ibish Asllani with sons Azemin and Xhemajli, Ramë Bakia, Dan Zeqi, Smajl Ibra, etc.

Mehaj – Zek Sokoli, Hysen Salihi, Haxhë Mehi with son Mehi and brothers and nephews Ibish and Avdyli; Bush Salihi with brothers Mursel and Hysen; Hazir Zeneli with son Bajrush and brother Nezir and nephew Mehmet; Bush Nuri with brother Reku; Sali Salihi; sons of Sali Murseli: Galo Reku, Mursel, Basha, and Hyseni; Smajl Ahmeti and Ibish Ahmeti, sons of Meh Ibra: Rexha, Hyseni, and Qerimi.

Selimaj – Hasan Bardhi, Muj Bardhi, Sadik Selimi, sons of Sadik Selimi: Arifi, Jashari, Brahi, and Lushi, etc.

The worst period was 1912–1916, when the villages emptied of Albanians were settled by Montenegrin colonists, who became violent landowners up to the present day. They claimed, “The state gave us the land.” There were cases where Albanian landowners were killed, and the colonists became owners of the seized property—for example, the three sons of Dakë Gjel: Osman, Bajram, and Musli were killed on their own land to make way for the Tomoviqs. The colonists had support from Montenegrin neighbors and Cetina. This situation made it difficult for Albanian landowners to return during 1916–1918.

Nevertheless, in that dark calm, the families from these villages who had taken refuge in the areas of Plavë and Guci, in Malësia e Madhe, Malësia e Gjakovës, Kosovo, and elsewhere, began to return. The return to their lands was delayed, as it began shortly before the Austro-Hungarian forces left Guci. Restoration was also short-lived, because the pursuit of the previous occupier left vacancies for several months to be led and organized by the locals. In late autumn 1918, Montenegrin-Serbian forces attacked these areas, and by early winter 1919 they imposed even harsher control. Pop Gjorgji had converted a large portion of the population to the Orthodox faith. With forced conversion, not only were they baptized with new names—Tahir became Trifun, Veseli became Vejso, etc.—but their surnames were also changed, for example, Nuacaj became Novoviq. Thus, each surname was modified with a Slavic suffix: Ujkaj → Ujkiq, Tahiraj → Tahiroviq, Drejaj → Dreiq, Mekuli → Mekuliq, etc. Settlement names were also changed, such as Pepaj → Pepiqe, Nokshiqi → Novshiqe, etc.

Regarding the tortures in these areas, the English traveler Edith Durham wrote:

“People’s names were made under torture. People were forced to stand in icy water until they begged for mercy. Every day, the town crier would call through the streets: ‘Today the government will execute ten people.’ No one knew the reason or who would be killed. They were forced to dig their own graves to be thrown in more easily. After shooting them, they would even dance over the bodies, without regard to whether they were alive or dead.”

Thus, wherever they went, they tried by all means to impose Slavic names, aiming to falsify the truth. As if out of spite, European conferences and congresses clashed over this region with a hostile spirit. Denying them the chance to heal their first wounds, the new occupier inflicted even deeper ones.

The population of these regions dreamed of better days, to be saved from Avro Cemi, Pop Gjorgji, and their collaborators. At that time, there were still Albanian bands in the mountains, because the period without occupiers was very short. Only from mid-December 1918 to mid-February 1919 can be considered the period when local leadership began to reassert itself. Even though brief, it brought some relief to the population of the area.

ONGOING MASSACRES

The situation escalated to the point where the Austro-Hungarian forces were violently pursued, and from February 20, 1919, the entire region began to be attacked. The first targets of the attackers were again Zhanicë, Pepaj, and Nokshiq, burning even the few huts that had been built for temporary shelter. The first massacre was committed against the brave Halil Shabaj. Resistance by the volunteers defending these areas was impossible against a regular army, such as that of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The harshness of the operation had a basis, as declared by a general of the Yugoslav army on February 13, 1919:

“The Arnauts from the region of Plavë and Guci, 600 men, were defending against Montenegrin attacks in Polimle (Lower Limit-H. Gj.).” He said, “These cases surpassed those of 1912–1913.”

Also, the Montenegrin colonel reported to his supreme command that “3,000 people were forced to flee to Shkodër…,” without mentioning that in the center of Plavë alone, 450 were left killed. Not to mention the villages that had already been burned.

THE CRUSHING KINGDOM

Life under the rule of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (SKS) brought new, different, and more sophisticated methods of torture, carried out in silence. The inhabitants experienced the worst. They were killed without trial, without choosing a particular time or method, even having their heads cut off in front of their children and parents.

To better understand the events surrounding conversion, we take some examples from Montenegrin writings. R. Veshoviq states: “…Most were crucified out of fear.” N. Duciq adds: “…The Montenegrin leaders used coercive means to convert them to the Orthodox faith.” The situation was carried out with knowledge and military planning. As learned from a telegram sent to the Supreme Command of the Serbian Army (March 20, 1913): “The Montenegrins are applying terrible pressure on the population regarding baptism. They are forcing even the Catholics to convert to the Orthodox faith. … In many cases, where there was resistance to conversion, it ended with murder. Those baptized by the priest in the herds were immediately sent to the stream or river to wash their faces and other wet parts, rubbing them with sand until they bled.”

Fedo Qullafiqi notes: “The cannonballs fired at Plavë resembled a ‘show of force’ adventure… The tragedy was mostly experienced by the elderly, women, and children, which is a tragic tally of the drowned and wounded!” Besides the mentioned crimes, other inhumane acts were used, such as rapes, indescribable massacres, house burnings, and looting in various ways.

Most of the victims ended up in streams and rivers, and even today traces of blood are visible on mosque walls. This heightened their consciousness and national awareness, preparing them for the second wave of violence, while their patience and suffering increasingly turned into hatred toward the occupier.

Franjo Jukiqi rightly wrote: “The people of Guci and other highlanders of the Shkodër Pashalik only know the name of the Pasha of Shkodër, while they govern themselves.” Since they resisted every act of violence, the Turkish occupiers called this region the “Cursed Land.” P.A. Rovinski used another term: “The dragon-infested zone.” The beauty of these regions also prompted the traveler Zuko Xhumbur to say: “…Heaven on this earth begins in Guci.” An equally astonishing beauty led Cvijiq to write: “…This region is among the most beautiful in the Balkan Peninsula…”

Patriots of the Albanian movement in Plavë and Guci had established connections with other Albanian regions. This unity strengthened the movement, which included many brave men from the villages of Zhanicë, Nokshiq, Pepaj, and other areas. Such a force pushed Aleksandar to order: “…If Plavë and Guci resist, flatten them with cannon fire, sparing neither women nor children.” (Shortly, 1919)

The stronger the armed bands became, the greater the violence against the innocent Albanian population. Albanian kachaks and armed groups were oriented toward the liberation of Albanian ethnic lands, relying on the principles of the League of Prizren, later Peja, and subsequent positions (1908–1912). The village of Velikë was exploited as a point of contention by Cetina, as it lay among Albanian villages—Rugovë, Meteh, Zhanicë, and Nokshiq—so national- and faith-based killings among neighbors were frequent. To remove Zhanicë and Nokshiq, Cetina seized part of their land so that Velikë would connect with the Lim River.

Clashes between bloodied groups were frequent, especially over meadows known as Nokshiq’s lands. One day, the Nokshiq men, returning from Zhanicë after arranging a marriage, at Rrasa e Mulës, fell into an ambush set by Velican forces, who also fired at them. In that clash, Deli Maliqi and Ibish Asllani were killed, while Man Dishi and Avdyl Shabani were wounded. On the Velican side, Simon Knezheviqi and Millosav Knjezheviqi died, while Bek Millosavi and Millovani i Vogel, a well-known kachak in the area, were wounded. After this incident, Millovani i Vogel called the Nokshiq men for reconciliation, who agreed under his oath that “I will not use bullets against the Nokshiq people.” Informants noted that he did not keep the oath.

Following these events, Zymer Maliqi fell into an ambush organized by the Velicans in Skiq. Life under the Yugoslav kingdom was violent. Albanian kachaks often carried out intermittent attacks against the occupiers. Every attack, no matter how small, was met with tenfold violence by the occupiers, leading to tragedy for the non-Slavic inhabitants living in these regions. Methods for eliminating the most well-known young men were even applied on market days in Guci and Plavë, when Montenegrins would point and say: “There, he looked at me!” or “He killed my father!” Arrests ended in death. Often, they even appeared as “friends,” telling victims: “Go, you are in danger,” before setting traps and killing them.

From 1920–1940 in Plavë, the “Black Council” existed (composed of 14 members). In Guci there were 5 members, and in Murinë: Vaso Zeljov, Laban, Radisav Peshov, Vuksan Gojkoviq, Leko Popoviq, Punisha Drakuloviq, Ognjen Garçeviq, Vujo Bozhov Zogoviq, Dushan Popoviq, and Rajko Saviq. By their order or knowledge, over 200 people were executed in the region. From just three villages, the following were killed:

- Vesel Bacaj (14), medrese student

- Hasan Bacaj (in Bun te Dulit)

- Galo Bacaj (in Llaze)

- Mustafë Bacaj (in Pepaj)

- Brahim Drejaj (in Pepaj)

- Hajdar Drejaj (in Pepaj)

- Tahir Drejaj (in Pepaj)

- Gjon Leka (in Bun te Dulit)

- Niman Drejaj (in Zhanicë)

- Four Dakaj brothers (in Mis-Bjeshkë of Pepaj)

- Azem Miei (in Nokshiq)

- Sokol Shabani (in Nokshiq)

- Dervish Asllani (in Zhanicë)

- Tafil Leka (in Zhanicë)

- Shek Buçaj (in Vraçevë)

- Elez Buçaj

- Mehmet Buçaj

- Sinan Ibishi (in Velikë)

- Vesel Gima (in Murinë)

- Idriz Drejaj (in She te Pepajve)

- Niman Bugaj (in Bun te Dulit)

- Islam Buçaj (in Shalë)

- Brahim Shalunaj (in Shalë), etc.

Regarding the fatal wounding of the student Vesel Bacaj, I learned that he was “wounded by Xhudoviq.” After being wounded, Vesel entered the house of Mileta Peri, and his first and last words were: “The Xhudoviqs killed me.” Mileta felt compelled to take revenge, confronting the assailants with resolute words: “This is how men are killed, not by pampering, and I leave it to the dead.” (April 1941)

The fall of the Yugoslav Kingdom broke the strength of the Serbo-Montenegrins, who believed they should always dominate, yet even they found it difficult to accept defeat as reality.

Nevertheless, in April 1941, the Albanians of this region were prepared to integrate into the current events, which came to be called the “Time of Albania.” For these highlanders, frequent joys could bring pain, while grief brought very little happiness. How could the inhabitants of the Plav and Gucia region not prepare themselves, not organize into voluntary civil-military formations, not respond to the call to defend the homeland, when the Chetniks aimed to exterminate this non-Slav population, as previously ordered by Alexander?

To illustrate this further, let us read the statements of Chetniks given on the Greben, Zeletina, and Vizitore peaks, from which they had a view of the Plav and Gucia Valley. From these observations, they divided the lands and territories of the indigenous population, dreaming of settling colonists after subjugating the Plav and Gucia region and removing the non-Slav inhabitants.

The young locals asked their superiors: “Where and who will be settled? How much land will we receive? How will life be organized after this war?”

All of this is reflected in a statement sent by Captain Milikiqi to the chief Chetnik Pavle Gjurishiq, which read: “While inspecting the region (the front line – H.G.) … I observed that, for the large number of people, there was great interest in the method of settlement on the Albanians’ property, as had been promised even before the war… that each would have sufficient land once the old elements (indigenous Albanians – H.G.) were cleared. This question may seem ridiculous to raise now, but the matter is very important, indeed crucial, to us.”

The following questions were posed:

- Is the supreme Chetnik command preparing such a plan?

- Will the settlement/colonization occur after the region is cleared?

- Will tribal disputes be monitored, which could escalate?

- Will the colonists receive property taken from former thieves and agrarians of Yugoslavia?

- Will climatic conditions in some areas (from which the colonists come – H.G.) and the needs of our mountain-raised population be taken into account?

Most believed that once the land was good, the settlers would protect it with rifles for what they had fought for… they wanted an answer.

Such thoughts expressed extreme distrust, keeping alive fears of the past: 1912–1913, then 1919, and so on. These circumstances became a source of inspiration for the great son of this region:

“…Is it the fault of the Albanian if his eyes burn watching others being driven from their homes? Is he guilty if he is and when he cannot be otherwise, because blood has been shed on his hearth and the living cannot be extinguished?”

Volunteer Mobilization

Such circumstances led to 4,500 volunteers gathering in Zhanicë, coming from other Albanian regions, to defend this area. The volunteers from more distant regions were led by their leaders: Sali Mani, Mehmet Bajrami, and Adem Bajrami (from the Krasniqe clan), Kadri Smajli of Dragobi, Isuf Alia of Gashi, Muharem Bajraktari of Luma, etc. They arrived with 1,800 volunteers. The regional leadership appointed Idriz Omeragaj as the police commander in Zhanicë.

Italian Occupation (April 1941)

In April 1941, these areas were occupied by Italian fascist forces. The residents of the Plavë and Guci regions hoped for better days, dreaming of a life without violence and the liberation and unification of Albanian ethnic territories. These developments worsened relations with Montenegrin neighbors, whether on national, religious, or ideological grounds.

The initial Italian appearances offered a kind of “pampering” freedom compared to recent times. Such gestures began to convince even the local leaders. The Italians’ persuasive declarations emphasized that separation from the Andrijevica District would bring positive changes for the population, since these areas would henceforth be ruled from Tirana, never from Cetina or Belgrade, which increased hope among the Albanian population.

Italy-Germany Agreement (April 23, 1941)

Hope was further raised when they presented the content of the Italy-Germany Agreement of April 23, 1941, which called for the unification of Albanian ethnic territories. This acted as opium to more easily deceive the Albanians. To confirm these claims, the local leadership sent a delegation to Tirana, which brought back the news that Tirana would become the administrative center of Guci, thus uniting the Albanian ethnic territories.

Formation of Volunteer Units

After these developments, the local leadership formed civil-volunteer units from the local population. These forces not only raised the Albanian national flag in Guci and Plavë, but also displayed it at Qafë e Previsë, the very site where in March 1913, 700 residents of the region had been executed by the extended hand of murderers.

At this time, in the Vasojeviq region, two ideologies were active: Russian-communist and Chetnik. Similarly, in the Plavë and Guci regions, both Russian-communist and fascist ideologies appeared. Chetnik ideology was also present. The Serbo-Montenegrins, as carriers of these ideologies, cooperated whenever issues arose concerning the Plavë and Guci region, joining forces to achieve Chetnik objectives.

Violence and Retaliation

As an illustration, on July 27, they set fire to three villages: Zhanicë, Pepaj, and Nokshiq, leveling them to the ground and even destroying the mosque. I know it was wrong, but I also hate to admit it—Albanian volunteers burned many Montenegrin houses in Ulcinj at the Limit. Innocent people were also killed.

During this time, Plavë gained the status of a sub-prefecture of Peja; Riza Feri was elected as chairman, and under him a commune was established. In Guci, Halim Prushi was appointed for a short time, later replaced by Sali Niko. In Plavë, Shemsi Feri was appointed, and in Zhanicë, the commune chairman was Avdiu i Avdiqe. The Zhanicë commune included the villages of Zhanicë, Nokshiq, Pepaj, Murinë, Mashnicë, and Velikë, covering the entire Upper Ulcinj area at the Limit.

Border tensions were tragic, and innocent people were killed on both sides. The region had its own local civil-volunteer forces, and many volunteers arrived from other Albanian regions as well. These units were led by authoritative leaders whose goal was the unification of Albanian ethnic territories. Some of these leaders came from the local villages.

Italian-German Occupation Policies

The Italian and German occupiers each had dark policies. Their interest was to make neighbors kill each other so that they could rule more easily. In the Zhanicë, Nokshiq, and Pepaj villages, all adult men were organized into volunteer units, taking shifts. Among them were: Imer Maliqi, Bajrush Haziri, Ukë Dema, Xhemë Tahiraj, Halil Huli, Azem Gjelaj, Sokol Shabaj, Imer Muça, Dervish Asllani, Malush Bajrami, Haxhi Syla, Arnaut Rama, Ibish Sadiku, Hasan Salihi, Dan Zeqi, Celë Mani, Niman Duši, Cenë Gjelaj, Hysë Selimi, Reko Meti, Smajl Halili, Azem Mehmeti, Halil Hyseni, Shaban Shabaj, Latif Muça, Lekë Prela, Ali Ferizi, Hysen Keka (Bacaj), and others.

Personal Memories of Hoxhë Pepa

“Let me tell you my entire life from seven to one hundred years, because we were all in the camps,” said Hoxhë Pepa (90), pausing to let out a sigh that shook his body. “I lived my life in misery and suffering, but fear never occupied me—I was always triumphant. In childhood, I was scared by a neighbor’s dog and a rooster. My grandfather arrived just in time. He was tired from running, didn’t speak, but unfortunately, with a slap like an eagle’s claw, he grabbed me by the neck, stopping my scream and even my breath. In that silence, I heard the roots moving in the hay, and my eyes were popping. He gave me some slaps. For my age, they were unbearable. Walk and shout, I told myself. ‘Next time, when I feel the slap, I will take his head off!’ he told me after slapping me.

The second slap I experienced in a communist prison (1946), when a Montenegrin UDB agent said: ‘From today, together with Balli Kombëtar, the priest will die.’ I asked, ‘But am I left now without Halil Drejaj?’ ‘Halil yes, but also Drejeviq,’ he replied. The third time I would explode, as if I knew they would not leave my bones in Pepaj.”

Memories of Reko Metë

Two decades later (1985), I met eighty-year-old Reko Metë from Zhanicë, who recounted childhood experiences in his birthplace. “When they killed my uncle, I was so angry, my tears were ripened by rage, and I thought I would take revenge without crying. I loaded my sixteens, they bought me the weapon, and then I realized it was too early, but necessity spoke for itself. In these border villages, we were always forced to be prepared to respond to enemies. We never had sweet sleep, nor comfortable food. We never stayed without guards to avoid surprise attacks. Even when we buried a martyr, we kept watch around the grave. Let me be buried in Albanian land wherever the child wishes, but I know where my soul will rest best,” he told me. He finished the story with a loud voice, as if he were there.

Memories of Cenë Asllani

I met Cenë Asllani (80) at his son-in-law Ali Rexhepi’s house in Vuthaj, 1968. He said in his first words: “If I were not near this family, I would not speak a word about the past. Since I was betrayed by the pledge that the Albanian partisans gave us, I suspect every case. That pledge put me in front of the Yugoslav OZNA, and even in the presence of those who brought me the pledge, they broke all my front teeth, which at that moment were my only weapon to resist disagreement.”

Interrogation and Betrayal

I knew they would not fire bullets, but that is how it was for them. Without stopping, together with insults, they rained their fists on me until I was half dead, because my hands were tied behind my back with wire. My mother used to tell me, “You escaped through the barrel’s mouth.” As a child, I did not clearly understand the meaning, but I learned it during frequent calls to arms. The barrel itself kept speaking, as long as I was alive, until suspicion arose that I had betrayed them. It was fitting to trust my elders when they said, “There is no pledge from the wicked.”

While I was asking Cenë questions, my uncles judged me with gestures, wondering why I made the man relive sufferings and memories from decades earlier, from the time when he held a weapon in his hand. Not to mention the suffering in prisons. When he recalled the first encounters with OZNA, he seemed ready to swallow his own beard. When he rose to his knees, he felt as if he were again a peer with a weapon, young and strong for the call to arms. “They did not execute me, as happened to the Nuacaj brothers.”

Isa Selimi and Highland Hospitality

I met Isa Selimi (75) in Raushiq of Peja, a man respected by fellow villagers and also a standard-bearer. When I announced my visit, the response came loudly, as if he meant to lift the roof of the single-story house. Seeing my surprise, he said, “Welcome, I have taken hospitality upon myself!” As soon as it was heard that Isa had a guest, all the Tahirajs arrived, led by the outlaw Hys Selimi. It all felt like a return to the memory of highland hospitality in that region where they lived.

I thought it would be easier to talk about place names than to develop a conversation about the war. When they began naming them, I did not know who had the freshest and most precise memory. They spoke as if prepared. One mentioned names tied to events, another the slopes where he had guarded sheep. Fatimja also joined the conversation, explaining where they took water. Logu i Lojës and Vendkushtrimi were mentioned as well.

Family Memory and Loss

As I listed the family tree of the Nuacaj clan, Zekë Haxhi Syla’s face suddenly turned dark. He often said, “I remember my father, from whom I received no affection, because in many cases he was guarding the homeland and preparing for the call to arms.” Zekë’s mother, Suta, 93 years old, very old yet calm and with preserved memory, often intervened in the conversation, which I then used.

“My mother gave birth to me at a time when the Slavs were chasing us from the lands of the village of Martinaj. At that time, 700 people were killed at Qafë Previ, not to mention the valley of Plavë and Guci. They did not think of me, and after five years they named me Suta, only because I had escaped the ‘apocalypse.’ God granted me fate even with a good husband, though I experienced little joy. I experienced the burning of the house, the killing of three brothers-in-law and my husband. I did not enjoy the respect of my brothers-in-law nor my husband’s love; thus miserably I raised my children on the roads and in misery,” she said.

Mushak Idrizi and Communal Life

As soon as I greeted Mushak Idrizi, who was watering a meadow in New Raushiq of Peja, he threw down his hoe and came toward me. Leaving his work, he said, “I have left forever the land of my father and great-grandfathers in Zhanicë, so why wouldn’t I leave work for a few hours?” To speak more freely, I suggested we sit under the shade of a tree. “No one from the family sees us to host us. Let me come closer,” he continued.

Accepting my wish, he called out loudly, “O Brege! I grew up on the slopes of Zhanicë, and now all the neighbors and the village have grown used to me. They must know a guest has come. In Zhanicë we were several clans, but one complete brotherhood. Every event was shared, even guests, not to mention enemies. We rejoiced together and sometimes grieved together. Weddings followed tradition. If only the groom’s close kin were invited, his maternal uncle was included. If the invitation went beyond that, the standard-bearer from the Gjekaj family was invited as a special sign, understood as the leader of the wedding party.”

He then listed the families and clans invited, explaining in detail the rules of invitation, procession, and escorting the bride, comparing it to a funeral, since people said, “A bride and the dead must be escorted by as many people as possible.” He described water-sharing rules for irrigation, known and respected by all, with no remembered disputes. Each irrigation turn lasted 24 hours, with clear rules between fields and meadows. He gave examples of how many turns each family had and emphasized that no one was dissatisfied.

With effort and deep longing, old Mushak concluded his story by saying that not only had they left Zhanicë’s hills, but their children had also emptied Kosovo since 1996, when the road to America opened.

Other Memories and Testimonies

Hysen Seku (75) spoke similarly, recalling a great wedding in Nokshiq in 1938, remembered vividly, with songs, lahuta music, and rhythms made by mothers turning metal trays, surrounded by women’s singing.

In Peja, I met Brahim Beka Nuacaj, just past seventy, who remembered the past passed down through generations. Longing nearly turned his tears to stone, held back only by clenched teeth. His violent death at Serbian hands in 1999 took that treasury of memory with him.

I met Avdi Shalunaj (70) in Peja in 1981. Sighing, he said he did not know exactly where his ancestors’ lands were, but part of the land was still called the Plains of Shaluna. His ancestors left those lands after two Jokiq were killed in Velika. “Then you know that blood does not age,” he said, with his soul burning in longing.

Qake Sadika’s Testimony

Around the age of ninety, in Raushiq of Peja, I met Qake Sadika, a daughter of Zhanicë and wife of Dan Zeqi from Nokshiq. She did not allow me to ask questions and began immediately: “I long to see the graves of my parents. My father was killed together with my uncle and many villagers before our eyes. They had no pledge and acted so many times—may God not forgive them without punishment. Three times I returned to a house turned to ash. We were caught in treacherous ambushes near Plavë, locked in rooms, separated from the men. With us was old woman Xhuxhe. We were children; we did not understand what they wanted, only when they began touching our hair over the hay. They had smeared their fingers with filth; we saw that stain on each other. The room became unbearable from the stench. A group came and kicked the door open.”

Faces and Memories of Displacement

They came to take our faces. When they took the face and smelled the room, they turned back with their insults. That old woman spat our faces at that girl. The same story was told to me by Rushe (Mekuli) Prelvukaj. She also spoke of similar experiences.

Not by chance, in Kapeshnicë of Peja, I met Xhemajl Ibishi (80), wise in speech and sentimental by nature. He was the last resident of Nokshiq to move with his family from their ancestral lands. “I do not want to tell a single thing. I am a dead man since the day I left my homeland, leaving that beauty with blood, even from my uncle Kurt Asllani. How will the lone Ujkan Sokoli live? How will he welcome Shëngjergjin, Bajramin, or even morning and evening prayers…” I understood the bursting grief in his soul and therefore had no strength to trouble him further.

In New Raushiq of Peja, I met 80-year-old Avdi Ramë Gjelaj, who said: “I remember my childhood. Festivities like Bajram, weddings, and other celebrations delighted me. Now they ring in my ears, as if I were hearing the song ‘maje krahu’ sung by the brothers Halil and Muj Huli. I enjoyed the performances of well-known lahutars Azem Muca, Rrustem Delia, and Is Selimi. You also know how Arrnaut Rama, before execution, was asked for his last wish; he said, ‘Free my hands.’ What use are hands when your feet are tied? I am not a man to flee; I wanted to strike a song into his ears.” His hands were freed, but the song was cut in half. Avdi finished his story as if drawing those words from the corners of his eyes, which reddened.

Shared Activities

In Plavë, “Unit 51” was formed, a union of young men’s groups, among the most loyal for providing rapid assistance on the front lines and within these areas. Delegates came from the villages and centers of Guci and Plavë. Members from these villages included: Ukë Dema, Bajrush Haziri, Shaqir Zymeri, Halil Huli, Idriz Qelaj, Shaban Gjekaj, Cenë Asllani, Hysë Selimi, Tomë Bacani, Hasan Salihi, Brahim Delia, Niman and Gal Duqi.

In Guci, there was the Council of Reconciliation for the region of Plavë and Guci, which included representatives from the sub-prefecture. The three villages had a shared council consisting of Selim Zhuji, Hoxhë Pepa, Imer Maliqi, Ukë Dema, Malush Bajrami, Sadri Ujkaj, Sokol Idrizi, Muzli Cela, Tomë Bacani, Haradin Keka, and Zymer Istrefi. The main council in Guci included Xhemë Bajraktari, Imer Maliqi, Cenë Gjelaj, and Hoxhë Pepa.