by Joseph Dedvukaj.

Abstract

This chapter examines the role of religion as a legal and administrative pretext in the dispossession of indigenous Albanian populations during Greek nation-building from 1821 to 1945. It argues that while religion—specifically the category “Muslim”—functioned as the operative criterion in law, policy, and violence, the underlying outcome was ethnically selective: the removal or erasure of Albanian-speaking communities. From revolutionary violence and confessional state formation, through the Treaty of Lausanne and compulsory population exchanges, to the mass expulsions in Chameria, the chapter traces a coherent logic of exclusion. Assimilation of Orthodox Albanians and elimination of Muslim Albanians emerged as complementary strategies within a single nation-building project.

Introduction

From the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence in 1821 to the expulsions in Chameria in 1944–45, a long arc of state formation in southern Epirus and the Peloponnese reveals a recurring pattern: religion functioned as the operative legal category, while ethnicity and language determined the outcome. This chapter argues that the “Muslim” label—invoked at different moments—served as a pretext for the elimination, removal, or erasure of indigenous Albanian populations from territories incorporated into the Greek state. The process unfolded unevenly, through violence, law, and administration, but cohered into a single nation-building logic.

I. 1821 and the Birth of a Confessional State Logic

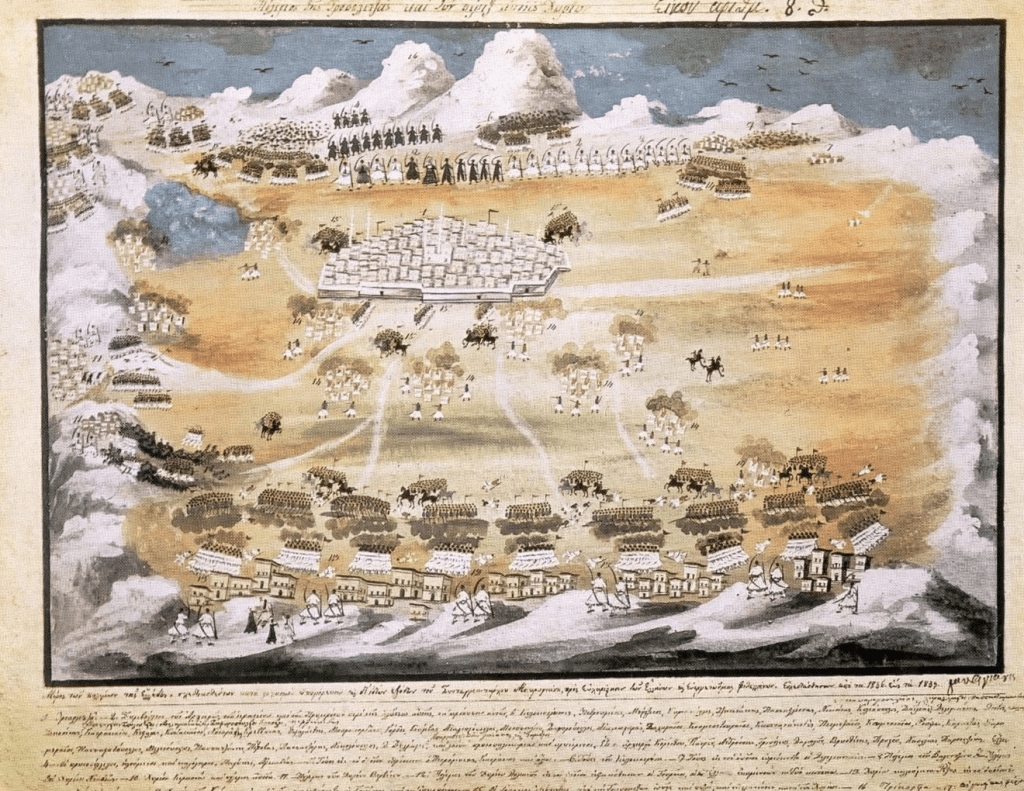

The Greek Revolution inaugurated sovereignty in a landscape populated by Orthodox Christians, Muslims, and Jews, including substantial Albanian-speaking communities (Arvanitika/Cham Albanian) embedded across Attica, the Peloponnese, and Epirus. Early revolutionary violence—most starkly the fall of Tripolitsa (1821)—targeted Muslims as a class, producing mass flight and killing. While framed as war against Ottoman authority, the effect was demographic: the near-total removal of Muslims from regions that would become the Greek core.

Crucially, many of those Muslims were Albanian by language and local origin, not “Ottoman colonists.” Yet the revolutionary state’s confessional lens rendered this distinction irrelevant. The new polity equated legitimacy with Orthodoxy; those outside it were expelled or annihilated. This was not yet a bureaucratic program, but it established a durable precedent.

II. From Confession to Administration: The 19th-Century Consolidation

As the Greek state consolidated, Orthodox Albanian speakers (Arvanites) were incorporated as “Greek” through church, army, and schooling, while Muslim Albanians remained structurally vulnerable. Language did not define belonging; religion did. The result was asymmetrical:

• Orthodox Albanians were assimilated (often with pressure and stigma against Arvanitika).

• Muslim Albanians were marked as removable, regardless of indigeneity.

This bifurcation—assimilation versus expulsion—became the state’s standard toolkit.

III. Lausanne (1923): Religion Codified, Ethnicity Erased

The Treaty of Lausanne and the compulsory population exchange (1923–24) formalized confessional sorting. “Greek nationals of the Moslem religion” were transferred to Turkey; “Greek Orthodox” moved to Greece, with narrow exemptions. The criterion was religion, not language or ethnicity.

In practice, this meant that Albanian-speaking Muslims in Greece—including communities in Epirus, Macedonia, and Thessaly—were deported to Turkey as “Muslims,” despite not being Turkish. The exchange completed what 1821 began: the administrative removal of Muslim Albanians from Greek territory. Ethnicity vanished behind a legal fiction; indigeneity was overridden by confession.

IV. Chameria (1944–45): The Final Cleansing

In Chameria, the pattern reached its most explicit form. Following German withdrawal, forces of EDES under Napoleon Zervas carried out coordinated killings, village destruction, and mass expulsions of Cham Albanians. Tens of thousands were driven into Albania; property was confiscated; return was barred.

Here again, “Muslim” functioned as justification. But the targets were ethnically Albanian, locally rooted communities, punished collectively and permanently. The violence continued after liberation, underscoring that this was not wartime exigency but territorial purification.

V. Legal Pretext, Ethnic Outcome

Across these phases, the pretext varied (insurrection, exchange, collaboration), but the outcome was consistent:

1. Collective targeting defined by religion.

2. Total dispossession (land, homes, civil status).

3. Permanent exclusion (ban on return; memory suppression).

The UN Genocide Convention framework—applied retroactively as standard in historical-legal analysis—captures this logic where killing, expulsion, and conditions of destruction are coupled with intent inferred from systematic practice. Even where scholars prefer “ethnic cleansing,” the genocidal elements are present when acts and intent are read together.

VI. Continuities After 1945: Erasure Without Expulsion

With Muslim Albanians removed, nation-building turned inward. Orthodox Albanian speakers (Arvanitika) remained, but under assimilationist pressure: stigmatization of language, absence of minority recognition, and the quiet rewriting of local histories. The crime persisted as denial—the maintenance of outcomes through law, education, and silence.

VII. Comparative Insight

The Greek case mirrors a broader European pattern where confession is used as law, and ethnicity determines fate. What distinguishes Greece is the temporal continuity—from 1821 to 1945—by which successive instruments achieved the same demographic end.

Conclusion

From revolutionary violence to international treaties and post-war expulsions, religion served as the legal key, but Albanian indigeneity was the lock being turned. The elimination of Muslim Albanians and the assimilation of Orthodox Albanians were not contradictions; they were complementary strategies within a single nation-building project. Recognition of this continuity is essential to understanding the modern Greek state—and to addressing the enduring injustices left in its wake.

⸻

References:

• Douglas Dakin, The Unification of Greece, 1770–1923 (London: Ernest Benn, 1972).

• Lambros Baltsiotis, “The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece,” European Journal of Turkish Studies 12 (2011).

• James Pettifer, The Greek–Albanian Borderlands (London: Hurst, 2001).

• United Nations, Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948).