Discovery by Dr. Qazim Namani.

Abstract

This study critically re-examines the origins of the Branković family through a comparative analysis of historiographical, ecclesiastical, and ethnographic sources. By engaging with the works of Leontije Pavlović, Todor Stanković, Ilarion Ruvarac, and the 17th-century chronicle of Đorđe Branković, the paper highlights significant contradictions in prevailing narratives regarding Branković genealogy and identity. Particular attention is given to evidence indicating Arbërian (Albanian) origins, including tribal affiliations with the fis of Gash and documented Albanian continuity in Kosovo. The findings suggest that later dynastic and national historiographies recontextualized the Branković lineage to fit evolving political and ideological frameworks. This reassessment calls for a more nuanced understanding of medieval Balkan identities beyond rigid national classifications.

On the Origins of the Branković family

Based on a comparative reading of several key historical and historiographical sources, serious inconsistencies emerge regarding the ethnic and genealogical origins of the Branković family. These inconsistencies suggest that the dominant historical narrative concerning the Branković lineage warrants critical re-evaluation.

According to the doctoral dissertation of Leontije Pavlović, defended in 1965, Gjergj (Đurđe) Branku was born in Albania and spent his childhood in Italy. He later entered Hungarian noble circles and ultimately became a Serbian despot. Pavlović acknowledges the Arbërian (Albanian) origin of Branku, yet the author appears to deliberately avoid explicitly addressing his ethnic identity, thereby obscuring a central historical fact.

Further evidence is provided by Todor Stanković, who states that the Branković families of Drenica belonged to the Albanian tribal lineage (fis) of Gash. This claim directly links the Branković name to established Albanian tribal structures, which traditionally preserved strong kinship and identity continuity.

In contrast, Ilarion Ruvarac, in his work published by the Royal Serbian Academy in 1896, asserts that the Branković family descends from Grgur. This claim introduces a different genealogical origin, one that aligns more closely with later Serbian dynastic narratives. However, Ruvarac’s conclusion appears to rely on retrospective dynastic reconstruction rather than on contemporaneous ethnographic or anthropological evidence.

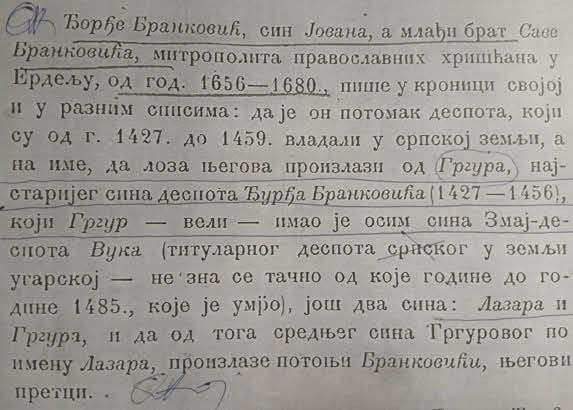

Additional complexity is introduced by the writings of Đorđe Branković (17th century), son of Jovan and brother of Sava Branković, Metropolitan of Orthodox Christians in Transylvania (1656–1680). In his chronicle, Đorđe Branković claims descent from the despots who ruled Serbian lands between 1427 and 1459, tracing his lineage to Grgur, the eldest son of Despot Đurđe Branković. From Grgur’s son Lazar, he claims, the later Branković line descended. This genealogical narrative, however, was written centuries after the events described and must therefore be treated with methodological caution.

The case of Maksim (born Maja) Branković further illustrates the transregional and multi-ethnic character of the family. Born in Albania in 1461 and raised in Italy, Maksim later became a Hungarian nobleman and titular despot of Serbia (1486–1495). He eventually renounced secular power, became a monk, and rose to high ecclesiastical offices, including Archbishop of Wallachia and Metropolitan of Belgrade and Srem. Ecclesiastical manuscripts and hagiographical sources emphasize his sanctity and dynastic prestige, yet these sources primarily serve religious and ideological purposes rather than objective ethnographic classification.

Finally, ethnographic data from Kosovo further complicates the picture. Families bearing the surname Brankovci in Masleševo, Velika Hoča, and Istinićë are documented as belonging to the Albanian fis of Gash. Notably, figures such as Suliman-aga Batuša are identified as relatives of Isa Boletini, a prominent Albanian historical figure. Such continuity of tribal affiliation strongly supports an Albanian ethnological origin for at least a significant branch of the Branković lineage.

Conclusion

When examined collectively, these sources—doctoral research, historiography, chronicles, ecclesiastical texts, and ethnographic records—do not form a coherent or consistent narrative within the conventional framework of Serbian medieval history. Instead, they suggest a complex process of identity transformation, political reclassification, and later historiographical appropriation. The evidence supports the premise that the Branković family originated from an Albanian (Arbërian) milieu and that subsequent narratives sought to reinterpret or obscure this origin in accordance with later political and national agendas.